In her famous ‘An Artist’s Life Manifesto’, Marina Abramovic states that an artist should not be depressed, and that depression is a disease that should be cured, because in fact it is not at all productive for an artist. This is repeated three times, and dispels the myth that all artists must draw inspiration from suffering, and constantly dwell in sorrow. And while it is not always easy to dispel stereotypes, a group of ten young artists have found the courage to try to do so: they explore this topic in a group exhibition called ‘Psychoes’, which opened on 17 September at the Klaipėda Gallery in Lithuania. The exhibition breaks down societal stigmas, and offers an opportunity to encounter and understand mental health through the lens of contemporary art, created specifically for this display between 2020 and 2021.

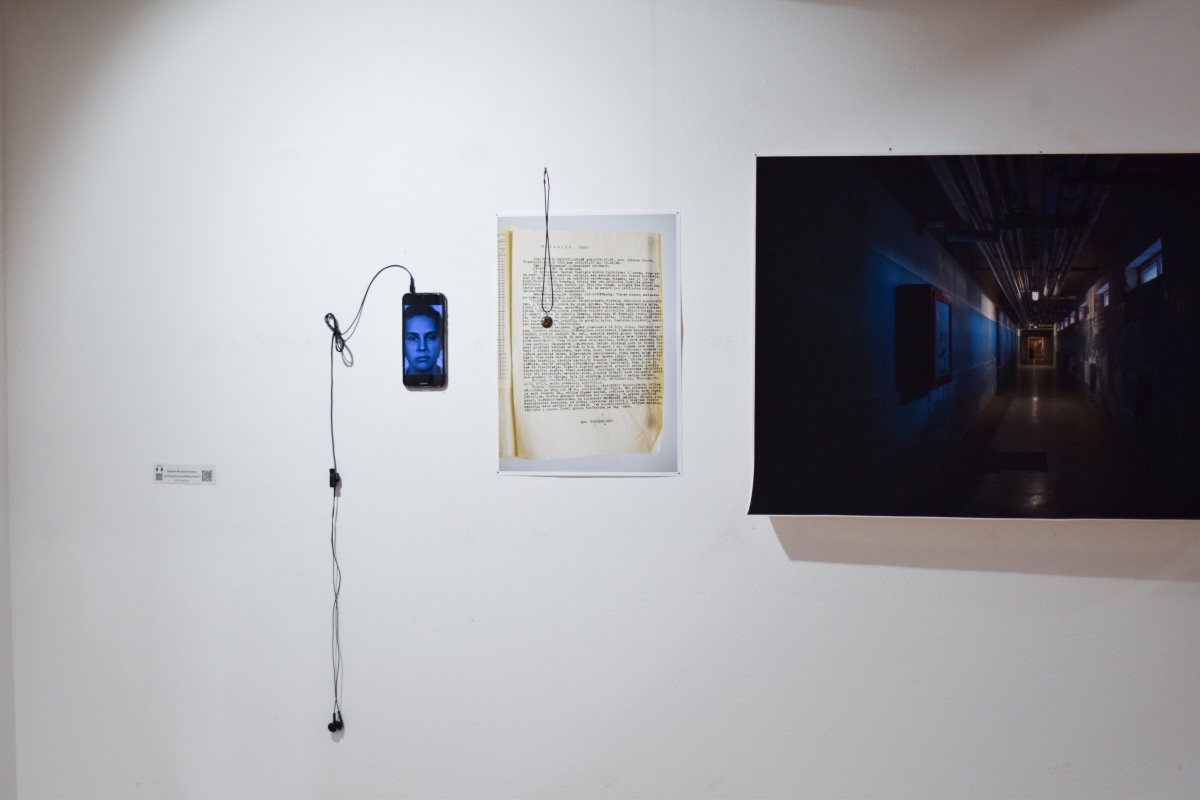

Language reveals our fears and past traumas. While we expect public opinion to change as the public become more aware, the daily vocabulary that accompanies psychiatric disorders is almost unchanged: ‘loony bin’, ‘a screw loose’, ‘freak’, and so on. The addresses of mental health centres in Lithuania (Vasaros Street in Vilnius, and Bangų Street in Klaipėda) are also often weaponised against people with mental illness. Of course, we cannot underestimate the historic memory of the systematic political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union. Remnants of these injustices still affect people living in the post-Soviet bloc, causing a mistrust of professionals in the field, and making them avoid seeking help in times of crisis. People are still ashamed to admit they been hospitalised in these institutions. That is why the installation ‘Psychogenic paranoid psychosis’ by the photographer Ingrida Mockutė-Pocienė is refreshingly bold and honest: the artist tells her personal story of being a patient in the Švėkšna mental health facility in the early Nineties. In western Lithuania, the name of Švėkšna is also often used as a way of taunting people experiencing a mental breakdown. Ingrida creates a photographic memory portal, taking us back 30 years. Ironically, the basement corridors of the psychiatric hospital have not changed in decades, once again indicating the neglect of mental health issues at a higher government policy level. The installation is accompanied by Ingrida’s voice, not only retelling her story to the viewer, but also expressing gratitude to the medical staff, and giving advice on maintaining good mental health. The corridors in Ingrida’s photographs are like a metaphor for the light at the end of the tunnel.

While Ingrida brings to life her teenage portrait with the help of AI, taken just before being institutionalised, Gražina Eimanavičiūtė-Kaščionienė, another participant in the exhibition, calls her creation ‘Death by AI?’, as if asking whether in the near future, when technology is much more advanced, human mental health issues will still be of concern to anyone. Gražina’s series of digital graphic illustrations is based on articles by the science-fiction writer Joe McMahon, in which he explores ideas about artificial intelligence, consciousness, technology, and the perception of information and time. We can already feel how technology affects our consciousness and our health. In Saulė Želnytė’s painting and video installation #24frames #insomnia, there is a clear reference to the blue screen light emitted by various devices, invisible but dangerous to our eyesight and our psyche. By simulating daylight, it interferes with the body’s natural production of the hormone melatonin. This disrupts the natural circadian rhythm, and upsets the mental balance. The artist notes the importance of a good night’s rest as a remedy for many mental hiccups and overthinking. When the law came into force in Lithuania this year that only psychiatrists can prescribe sleeping pills (and not family doctors, as was the case before), it became clear that a kind of pandemic of insomnia is spreading in the country.

But not everything is gloom and doom. The series of drawings ‘Self-love’ by Viktorija Dambrauskaitė calls for doing just that, learning to love yourself. The artist appeals deliberately to the Instagram aesthetic, slightly mocking its obsession with forced positivity and cringe-making slogans, like ‘good vibes only’. Social media made open conversations about mental health-related issues mainstream and normal, but it also romanticises mental health challenges, which is dangerous, because it sets unrealistic expectations and standards that are harmful to an individual’s mental health. To quote Oscar Wilde: ‘Everything in moderation, including moderation.’

But not everything is gloom and doom. The series of drawings ‘Self-love’ by Viktorija Dambrauskaitė calls for doing just that, learning to love yourself. The artist appeals deliberately to the Instagram aesthetic, slightly mocking its obsession with forced positivity and cringe-making slogans, like ‘good vibes only’. Social media made open conversations about mental health-related issues mainstream and normal, but it also romanticises mental health challenges, which is dangerous, because it sets unrealistic expectations and standards that are harmful to an individual’s mental health. To quote Oscar Wilde: ‘Everything in moderation, including moderation.’

Agnė Matulionytė presents some cognitive dissonance in her installation Psyche. From outside the installation, we see colourful orderly shapes, but when you enter it, you see a black and white animation depicting a person’s inner world, where an existential crisis is perhaps taking place. The artist spent half a year hand-drawing over 1,000 frames for this animation. The activity was therapeutic for her: ‘It is symbolic that sometimes when you draw twenty-four drawings for an animation, not much changes; just as in life, you can feel the stagnation.’ The standard thinking has us believe that depressed people lose all interest in their daily activities, and cannot bring themselves to go to work or school, and their performance suffers significantly because of it; but the reality is that many people in this day and age suffer almost invisibly from high-functioning depression. Researchers claim that depression may inhibit the desire for activity and action, but high-functioning individuals tend to forge ahead, in an effort to achieve their goals. However, these people also need treatment for depression.

Group exhibition ‘PSYCHOES’ at the Klaipėda Gallery, 2021. Photo: Rosana Lukauskaitė

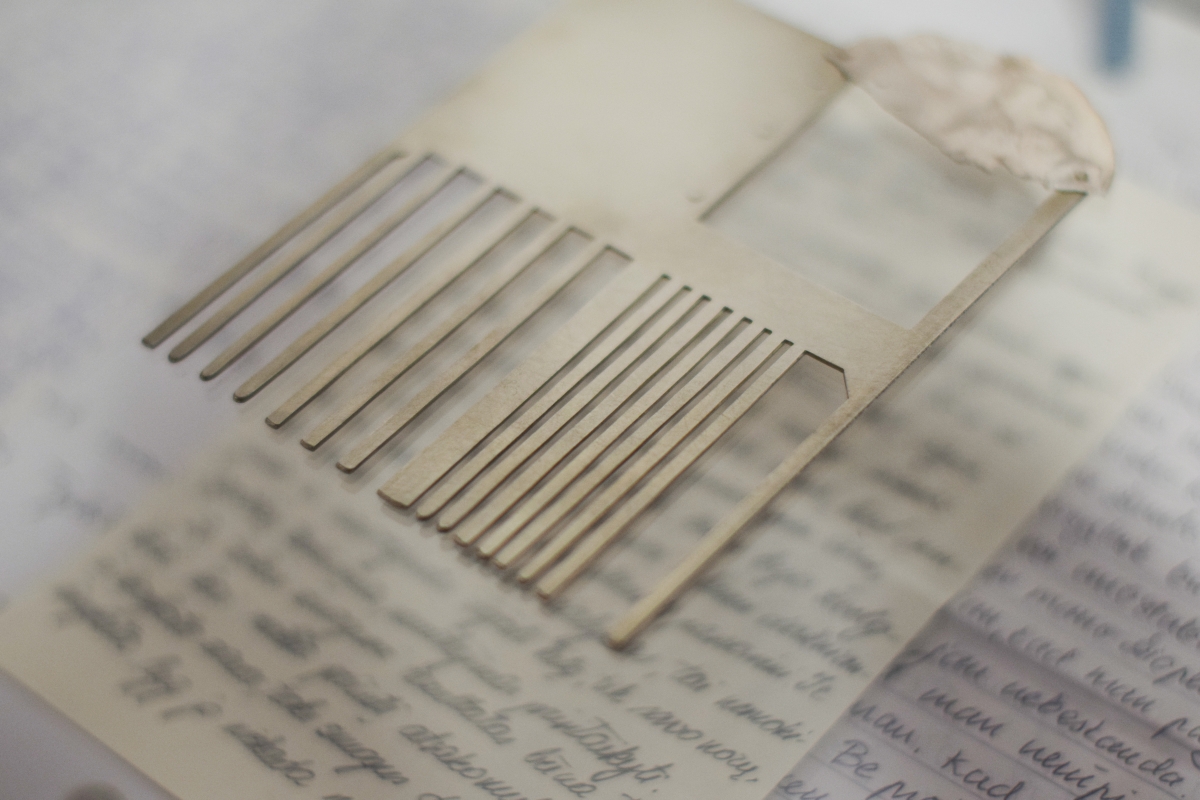

In her paintings and series of video performances ‘The End of Daze’, Aglaja Ray notes the need to seek treatment, and not just to wallow in your pain. Created in a desolate place during the period from 15 to 30 March, when Lithuania declared a state of emergency as a preventive measure against the spread of Coronavirus, the video works exude an apocalyptic mood. It is almost impossible to talk about lockdown without touching on issues of emotional health. During lockdown, creativity helped artists to come to terms with what they could not change. In her paintings Longing and The Calling, Aglaja captures that moment in time when she experiences a certain state, a foreboding that the time is coming not only to pour out her feelings through creativity, but perhaps also to consider the therapy option. The installation My Great Nan Used to Comb Herself by Simona Agota Martinkus also talks about the importance of opening yourself up to others.

The artist was inspired by warm childhood memories of the evening hair-combing rituals performed by her great-grandmother, who would share with the youngster her past pain and unspoken words about her experience, as if getting rid of what was unwanted. This gave birth to the idea of making combs objects d’art, and inviting anonymous people to take part in an experiment: to cut a strand of their hair and write a letter of confession, which contains the most intimate thoughts that they never dared to utter aloud.

In her painting series ‘Steps Leading to Silence’, Augustė Santockytė examines the mental disorder occurring after the loss of a loved one. Just like many difficult things in life, grief has many stages, with the final one, hopefully, being acceptance. Urtė Jasenka, in her triptych ‘Stations’, compares the experience of a person struggling with mental health problems with travelling by train: the symptoms occasionally go away, and the person may feel completely cured, but the disease often recurs episodically, and the same tracks and stations repeatedly reappear. What is not contained in the images is expressed through sounds: a music track created specifically for the project by the singer-songwriter Ingaja expands the experience of the exhibition, and adds a meditative atmosphere.

All art is, by proxy, about the human psyche. While exploring the impact that mental illness is having on society, art can play the role of both encouraging positive self-expression and guiding effective mental health promotion and treatment. There is a lot that we still do not understand about the human brain and various personality disorders, but after years and years of misrepresentation and shame, the term ‘mental health’ is slowly losing its stigma. We can only hope that the exhibition ‘Psychoes’ (provocatively reclaiming a term often used to demean people) helps to normalise mental illness the way physical illness has been normalised, and starts a constructive conversation about mental health.

Group exhibition ‘PSYCHOES’ at the Klaipėda Gallery, 2021. Photo: Rosana Lukauskaitė

Group exhibition ‘PSYCHOES’ at the Klaipėda Gallery, 2021. Photo: Rosana Lukauskaitė

Group exhibition ‘PSYCHOES’ at the Klaipėda Gallery, 2021. Photo: Rosana Lukauskaitė

Group exhibition ‘PSYCHOES’ at the Klaipėda Gallery, 2021. Photo: Rosana Lukauskaitė

Group exhibition ‘PSYCHOES’ at the Klaipėda Gallery, 2021. Photo: Rosana Lukauskaitė

Group exhibition ‘PSYCHOES’ at the Klaipėda Gallery, 2021. Photo: Rosana Lukauskaitė

Group exhibition ‘PSYCHOES’ at the Klaipėda Gallery, 2021. Photo: Rosana Lukauskaitė