“Men dream of women. Women dream of themselves being dreamt of. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. Women constantly meet glances which act like mirrors reminding them of how they look or how they should look,” wrote the English art critic John Berger in 1972, in what was the starting point of the inquiry into the problem of the male gaze. A couple years later, film theorist Laura Mulvey stated the following: “Woman stands in patriarchal culture as a signifier for the male other, bound by a symbolic order in which man can live out his fantasies and obsessions … by imposing them on the silent image of woman still tied to her place as bearer, not maker, of meaning.”

Fifty years on, it still remains a resonant perspective, and Miķelis Mūrnieks’ exhibition confirms this, putting not just the viewer but first and foremost the artist into a strange situation. This series of works features twelve naked and beautiful women, twelve iconic apostles arranged inside a specific and sacral geometry of the exhibition space. Do Mūrnieks’ works embody the problem of the male gaze? Do they show it from a new perspective? Several of the works on show refer to images of ancient and Christian culture – Titian’s Venus, the three graces and Christian symbols, – which have become bearers of the dark burden of patriarchy. How can one look at these abstract nudes through the lens of feminism? Is a male artist at all capable of indicating a woman’s beauty without objectifying it? What constructs the gaze of this exhibition?

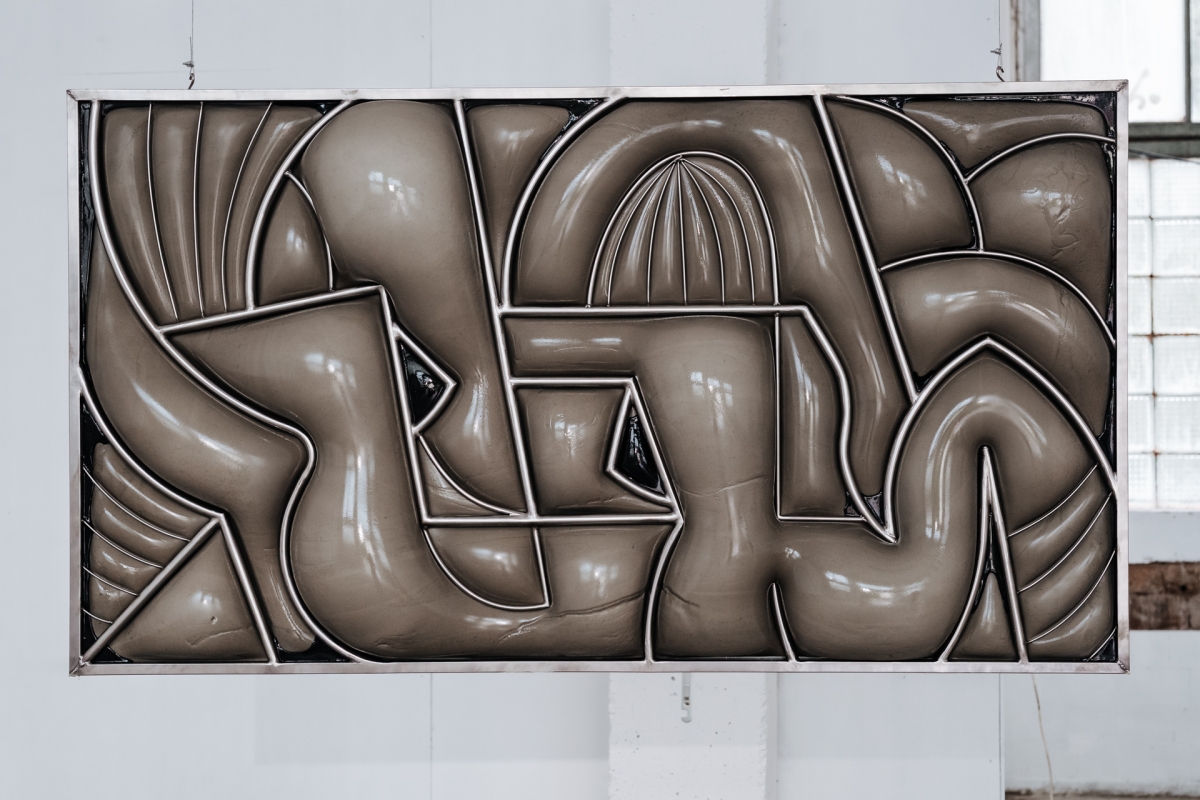

This series of works has been inspired by a desire to review the ideals of aesthetics, and this has led to a concurrently chaste and forward revelation, which is characteristic of Mūrnieks: the naked body of a female is, in his eyes, the pinnacle of beauty. The works’ visual language reflects a striving towards aesthetic pleasure, stylistically similar to the decorative elegance of Art Deco, while Hector Guimard’s Art Nouveau has left a strong impression on the form of the series.

Peeling off the layers of the exhibition, one slowly discovers a symbolic and nuanced opposition against the illustrating, objectifying male gaze. This is embodied by the works’ visual abstraction and the conflict among the materials which have been put to use. Polyurethane foam is pressing through the scrupulously built metal frames and latex, with Mūrnieks’ author’s technique leaving wounds, scars and stretch marks on the polished body parts of the female images.

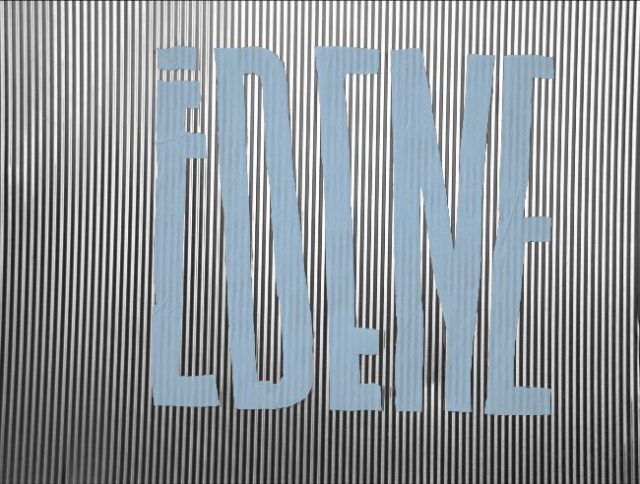

But the essence of this opposition, self-consciousness and experience is to be found in the title work at the center of the show, a construction that creates a conceptual, literal and physical counterweight to the beauty of Mūrnieks’ visual pleasure theory. Perhaps the opposite pole of the admiration of beauty is located in the still-current chauvinism and recognition of one’s sins? Are these matters perhaps too heavy to allow an innocuous pleasure? Be that as it may, it’s important to discuss them. Even if it makes one afraid that this line of thought could lead to appropriation.

Berger points out that nakedness initially appeared in European paintings through the story of Adam and Eve. In the Old Testament, the serpent tempts Eve into tasting the forbidden fruit, saying: “For God knows that when you eat from it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” Eve tastes of the fruit and gives it to Adam, “And the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together, and made themselves aprons.” Nakedness became sinful the very moment it was first observed.

Miķelis Mūrnieks’ works are continuously provocative with the density of their symbols. The silent images aren’t meeting the viewer’s eyes; they make their author naked instead, turning the searchlights of social criticism against him. The viewers are only caught by its reflection and the shadows it casts inside a space where nakedness of the body makes one self-conscious again. It finds its place somewhere between the faultless time in paradise and between pleasure and the Fall.

Henriks Eliass Zēgners

Miķelis Mūrnieks

Visual Pleasure Theory

May 26-June 5, 2021

Curated by Tina Petersone & Rudolfs Stamers

Hosted by Uldis Trapencieris and art venue ‘You know where’

Supported by State Culture Capital Foundation of Latvia, Valmiermuizas Alus, Avesco Rent, Sexy Style

Photography: Filips Smits