In September, a new institution, the Kai Art Centre, opened its doors in Tallinn. Situated in the port area of Noblessner, Kai operates an exhibition space and a residency, and also contributes to the local art scene in other capacities through various initiatives. The centre’s first exhibition, also part of Tallinn Photomonth’s main programme, ‘Let the Field of your Attention.… Soften and Spread out’, takes a sensitive approach to its core concept, as well as helping the new institution ease into being.

However, for the audience ‘Let the Field of your Attention.… Soften and Spread out’ is not an unchallenging exhibition. Even though it leaves ample space for visitors to make their own choices and shape their own experiences, it is demanding in a gentle but indisputable way. Without a very conscious choice to engage and stay with the show, it easily slips away.

The exhibition brings together eight artists, whose works are presented in varying degrees at any given moment: some are on show in their full extent throughout the exhibition period, but most need to be ‘activated’ at certain times, or through activities, be it with or without the author present. So, ideally, visitors extend themselves to the space created around the show multiple times, as each visit provides a different experience.

Pia Lindman. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

Borrowing its title from the field of bodywork, ‘Let the Field of your Attention … Soften and Spread out’ focuses on three central concepts: night; body/creativity/receptivity; health/wholeness/healing arts. These clusters, as the curator Hanna Laura Kaljo calls them, are in close proximity to one another, and all feed into the interwoven mesh of artistic practices the exhibition has drawn together for just over two months.

The central idea is to be present, to connect to our bodies, as we adjust to the passing of the seasons, the increasingly darkening and approaching winter in the northern hemisphere. To emphasise this further, the presentation cycles of some of the works follow the rhythms of nature; for example, they are synchronised with the changing hours of the sunset throughout the two months. Essentially, it feels as if the exhibition is about the passing of time, measured against your own experience, or vice versa. Making this palpable, however, is a difficult task. When walking through the exhibition space, many of the works have a distinct air of being suspended, of something missing. I do not mind this in the least; the opportunity to come back to a new experience next time is exciting; but I also know some parts of it will remain out of reach for me. Just like visitors, artists also come and go, making sporadic appearances throughout, leaving the audience to witness what they leave behind, and to wonder about the potentialities yet to be called into being. This very dynamic equation is nevertheless held together by a strong concept, and, in a more material presence, by the curator. It feels as if curating is understood as going back to the etymological roots of the word: to tend to, to take care, the curator as a caretaker. And I find that comforting. I love seeing that kind of care put into in exhibitions. It is not performative care, neither on the part of the curator nor on the part of the artist. For that, I am grateful. I am tired of seeing care performed; and even though I do want more of it in the world, I also want to find it where it is genuine and needed.

As for this exhibition, it is no Wellness TM or Mindfulness Inc, but rather comes from a somewhat different background: bodywork, and various therapeutic and healing practices. One of these is Nele Suisalu’s moving meditation, happening five times in total and beginning at sunset, one of which I was able to attend. The stated aim of this performance, but also of others, was to offer the audience a therapeutic or healing experience, guided by the artist. I found the performance enjoyable, and I did, above all, appreciate it as such; however, I am somewhat hesitant about calling it a therapeutic experience. I am not exactly sure what therapy means in the context of contemporary art. I am not opposed to the idea, but it is also unclear to me what we are supposed to be in therapy for? What exactly constitutes a therapeutic or healing experience in an art environment? For me personally, it is also an uneasy ground, because it suggests conflating an environment I experience as a place of work with something that is supposed to impact on me on a very fundamental level. And, honestly, I really do not think I am willing to diffuse that barrier. For someone else, approaching this from different ground, the experience is, no doubt, different, and, to be fair, this is also what the exhibition strives for, to allow a multiplicity of experiences. But even so, it can be difficult to find something to hold on to, except for yourself, I suppose, if you are willing to. However, I do not think this can be asked of everyone; it is not always possible to take refuge in yourself or your body, and it is no less valid to have and be a body on strike; against itself, its environment; against time.

In addition to asking the viewer to turn their gaze inwards, the show also suggests connecting to your environment. In most cases, this means aligning yourself with the surrounding landscape, as the artists mostly address (more or less) the natural environment in their practice, as has already been seen, or is still to be seen in the works of Sam Smith or Elin Már Øyen Vister, for example. The curator also draws from the particular surroundings of the Kai Centre, and the multiple layers of the historic district, mentioning the neighbouring former cemetery, the oldest in the city, and the century-old buildings of the former shipyard and submarine construction complex, now developed into high-end real estate. What seems to be overlooked, however, is precisely these new developments, processes that have resulted in luxury apartment complexes, restaurants and other commercial endeavours. So what does it mean to choose not to see the contemporary, while asking the audience to be present in the moment? The new material reality that has manifested with the recent and rapid development of the area has made it possible to bring that thinking into the area in the first place, but it has also considerably changed the socio-economic context, just as the development of the shipyard in the early 1900s did.

Workshop by Carlos Monleon Gendall

Thinking of the surrounding area in the present moment, to me another kind of similitude emerges. At a distance of 250 metres from the exhibition space, just on the edge of the cemetery park, sits a (techno) club, which in a way represents something that is closer to the aspirations of the show than any other place or space in the art centre’s surroundings, in the sense that it is not about the ‘how’, but about the ‘what’. In the club, too, bodies, time and wholeness take on a meaning that is radically different from anything outside the space. The shared goal in both spaces, the exhibition as well as the club, is to be as present as possible, and to find immediacy in and with your environment. What differs, though, are the means. In the club, time has evaporated, you stop holding on to it, and make your body move; in the exhibition hall, you hold on to time and submit your body to it, you keep it still. Depending of the specifics of your particular experience, what happens in either space can leave you restored, indifferent or frazzled; but, without a doubt, both present a very distinct way of managing and creating tension and release. Perhaps I see the similarity because of what is already in my body: it is in spaces like the club next door that I have learned so much about what my own body is capable of, with and next to other bodies, in the present moment, in the dark, in its wholeness. But be it in stillness or movement, whether through holding on or letting go, what matters is where we decide to take what was gained through the experience and not let it slip away.

‘Let the Field of your Attention.… Soften and Spread out’

Kai Art Centre, Tallinn, Estonia

21 September to 1 December 2019

Artsists: Marie Kølbæk Iversen, Sandra Kosorotova, Pia Lindman, Andrea Magnani, Elin Már Øyen Vister, Carlos Monleon Gendall, Sam Smith and Nele Suisalu

Curator: Hanna Laura Kaljo

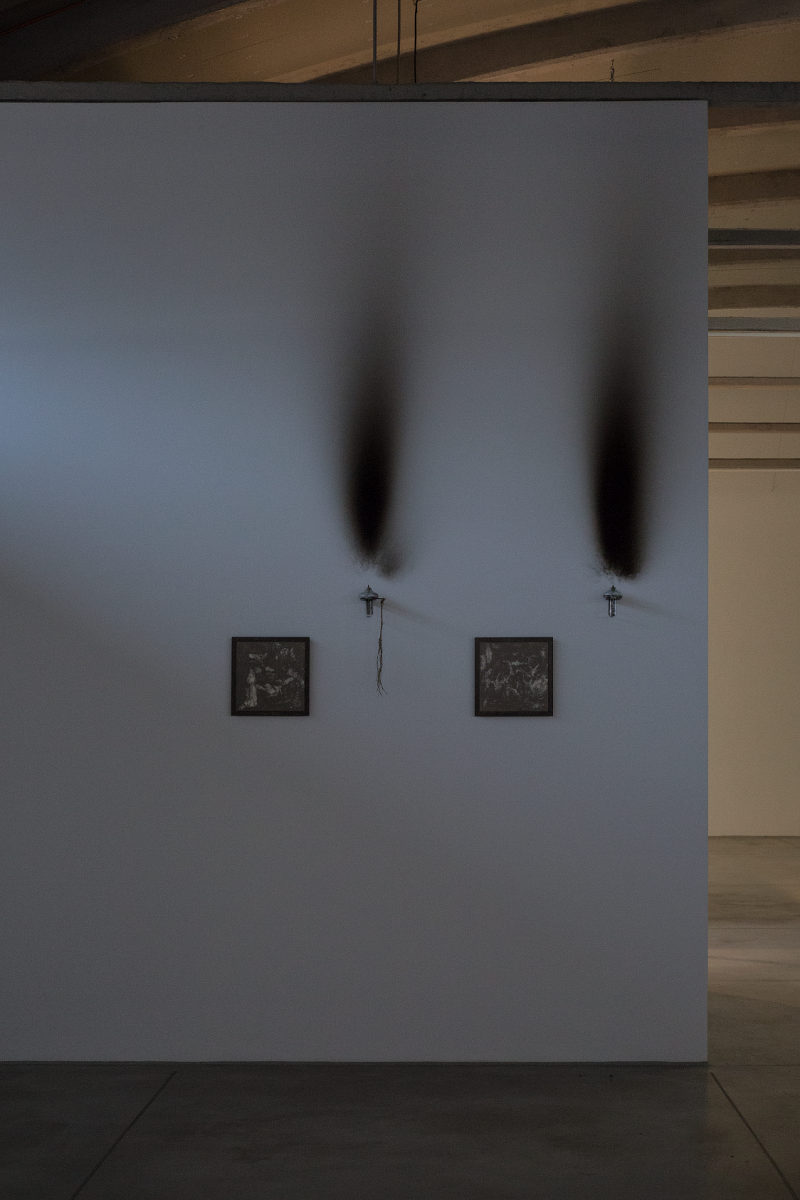

Night view. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

Andrea Magnani. Day view. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

Andrea Magnani. Night view. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo