Our climate recalled the tropics this year when the lime trees blossomed. The anxiety intensified that the world is diverging from an established regime. But will these changes give lime honey a sweeter taste? It is unlikely. Disregarding doubts, we avoid fearsome thoughts concerning a presumably insecure future, and continue taking part in our habitual whirlwinds: we go to work, we go on holiday, we buy products in plastic wrapping that we curse and swear about. Presentiment tells us that something similar happens when we approach the sunset of our personal life. In the evenings, it is expected that we will live out another dawn, just for the sake of morning joy, for something that has already been experienced numerous times. In other cases, hopes of sunrise are followed by vital fantasies shaped by new swings and scopes, domestic or creative. The latter are reminiscent of an everyday ‘footwalk’ by Jonas Mekas (1922‒2019), a cinema poet and visual artist, who always indulged in creative projects. However, one of the last projects initiated by him (it is not clear how many he had planned for the future) was continued by the curators Justė Jonutytė, Kotryna Markevičiūtė and Yates Norton, who prepared the exhibition ‘Let me Dream Utopias’ at the Rupert Centre for Art and Education.

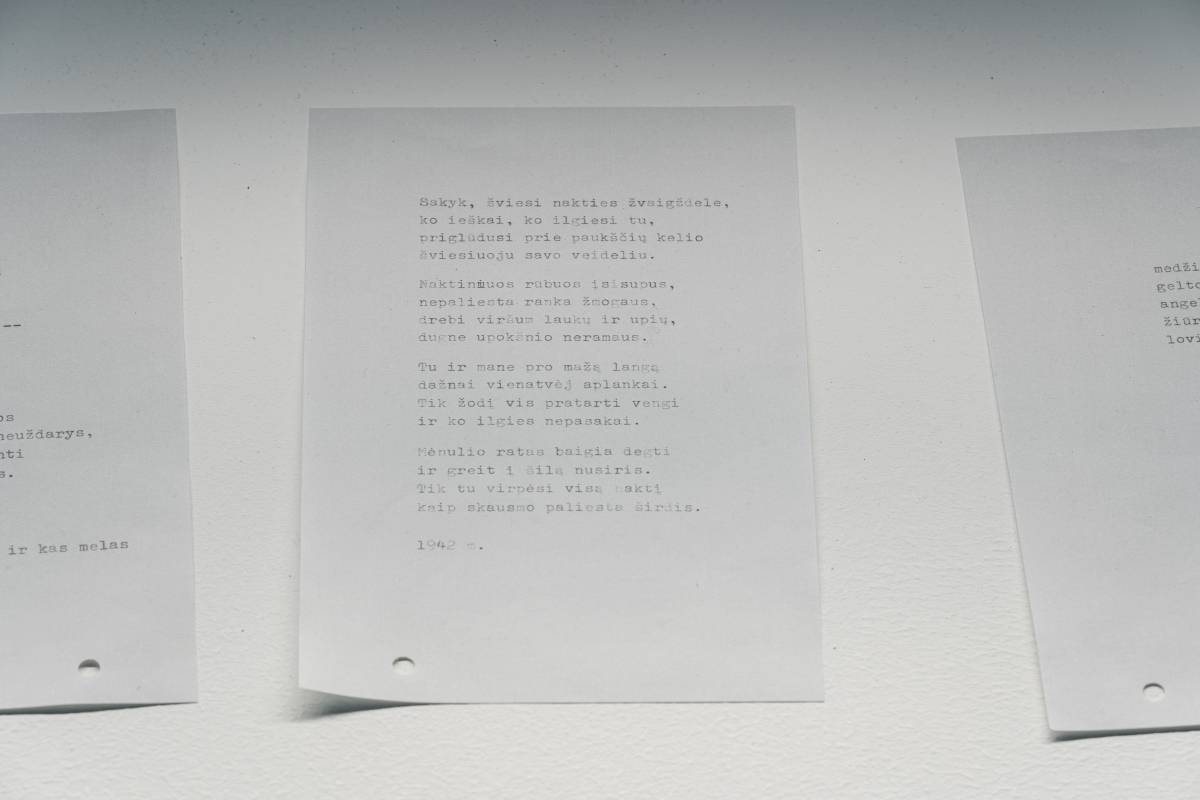

The project is already seen as a prelude to Jonas Mekas’ retrospective exhibition that is expected to be held at Lithuania’s National Gallery of Art in 2021. In accordance with the artist’s idea, the video works shown in the exhibition are supplemented with poems from his personal papers that have never been published before. The poems selected bring the artist’s past back to life. They were written in his youth, when he was still living in Lithuania, and later while living in camps in postwar Germany, and after making his new home in New York. The three different poetry notebooks cover an extensive period of his life, from the late 1930s up to the new millennium.

Displaying literature in a contemporary art space as the basis of an exhibition may appear as a challenge to curators. With great respect for the artist’s legacy, and sharing the genuine acceptance of his loss with his close relatives, the curators turned down the idea to implement the draft project that was worked out by Mekas himself without his own encouragement and authoritative supervision. It was also difficult to resist the temptation to complement the exhibition with photographic images at the discretion of the curators’ team alone. These absent initial elements of a visual narrative were replaced by architectural details projected for the exhibition space by Ona Lozuraitytė and Petras Išora. The architecture highlights Mekas’ poems, printed on white paper.

A significant element here is an all-in-one bench situated along the whole exhibition space. It becomes a unifying symbol for the artistic community, and eliminates the social distinction between the viewer and the subject of an exhibition. Other details are camera obscura-like projections, the exterior of the Rupert building, such as a staircase, interpreted as a timely situation, a semantic inside-out pathway, and even an upside-down bridge. This prosaic architectural solution recontextualises the transition from side-by-side towards beyond the mundane. Blurry images turn the white cube into a dreamy environment, that refers to the possibly implied utopian space.

Sterility is imposed. Corresponding with the immaterial imagery shown in video projections, it allows us to remember and reconsider the effects that the digital age has created for a communal response relating to the loss of the artist. This was followed by a flood of digital reproductions of Jonas Mekas’ photographic images in newsfeeds of social networks in an instantaneous manner, turning internet browsers into cinema reels. The effect found its resemblance in a framed image projection on one of the exhibition walls. The flatness of the objects and the somewhat predominant feeling of emptiness, hazily floating in the exhibition space, all together represent loss, and stand as a counterpoint to the aforementioned virtual domestic spontaneity: short messages expressing condolences, the sharing of stories and memories in personal profiles when the audience’s relationship to the artist varies to an unsurprisingly wide extent.

Jonas Mekas’ films Lost, lost, lost (1976) and A Letter from Nowhere (1997) are being shown silently, without external sound, and as such they refer to architectural sterility by limiting the number of viewers. This may also be seen as a way to reflect on the audiences, to which the artist himself was quite well known as an acknowledged personality, but his works were unfamiliar. Thus, the comparatively passive relationship between the audience and the artist’s oeuvre draws attention to the fact that there have recently been no comprehensive Jonas Mekas exhibitions in Lithuania, and opens up a complementary perspective on the shared initiative by Rupert curators and the artist himself for such an exhibition to take place in Vilnius. Finally, it shows great respect for a globally acclaimed cinema poet and his artistic achievements.

The exhibition’s title, borrowed from a poem presented among the other pieces, refers to the key notion of utopia. It would be difficult to ignore the significance of the term within the prospect of interpretation that opens up for the spectator. Works selected from an already-existing archive represent a close relationship with the personal past. Bearing in mind that the past is a place of no return, at least physically, as a utopia, it has more to do with the unreal than with the ideal. The flow of time gets hold of the film’s characters, if not by lifting them up towards the stars, then surely by enriching them with experience and knowledge. These life changes are accompanied by other circumstances. They lie in continuous relation to their times, events on various scales, and features of their epoch, hovering like dust clouds of allergy and sowing the sneezing that activates the dominant tendencies of lifestyle. The artefacts of time unfold in a cinema reel.

Without any doubt, the framework of time also transforms biographical film characters, who barely recognise themselves in images from the past. Is this really me? Bodily experiences and the experience of rationality become most vivid through memories of first times: the intensity declines with repetition. That is why we often say that we wish to see, taste or hear something for the first time again, so that we can experience the very first time, in all its uniqueness. Similarly, we would like to return to our past, and act or do something differently. This is because only on the way to the future do we get to know where decisions and results lead us, even without a guarantee of success. A longing for the past proves its utopian features, as something better, and perhaps even more idealistic. You cannot long for something that did not exist, and that is why we look to a future guided by another side of our feelings, with hope and trust for tomorrow.

Although it was mentioned that a return to the past is not possible by physical presence, as time is one-directional, Jonas Mekas had the privilege of a gifted artist to shape the past by employing different means: films, poems, diaries and photographic images. Different methods of creation enabled him to reanimate a subdued longing for certain moments in life, and find inner peace when facing the pulse of the past.

Since the poems presented in the exhibition are filled with an abstract play of words, like inanimate substantives, boys and girls, broad-brush sites as fields, hollows and valleys, we can easily recall our own memories by identifying with notions of universal experience in Jonas Mekas’ lines of poetry. These moments are given as a mouthpiece to the past, and if we allow ourselves to sneak a look, the thought arises: what if living in one’s own body is not the only form of existence? What if it is a port that connects us with other media, be it the pages of books, cinema screens, or a placeless sonic environment heard through headphones with our eyes closed.

Exhibition installation photos by Andrej Vasilenko, performance documentation by Saulius Ziura.