Maria Tobola, Amber Kebab, 2016, Collections, photo: Finnish National Gallery/Pirje Mykkänen

Šelda Puķīte: Let’s start with the title ‘There and Back Again’. Is that a conscious ‘Hobbit’ quote?

Saara Hacklin: Yes, it is, but only in English. It’s not there in the Finnish title ‘Meno-paluu’ though, which would simply be ‘round trip’ or ‘return ticket’. We were trying to emphasise the fact that the exhibition is not just about travelling. There’s a metaphorical or poetic dimension to it as well. Travel as transition, as a situation in which things happen.

Kati Kivinen: ‘Amber Kebab’, the title of a work by the Polish artist Maria Tobola, was also quite a strong candidate for the exhibition’s title for a while. The theme of amber as Baltic gold, and the Amber Road. We thought about this idea for some time. But some said that ‘Amber Kebab’ was too provocative, and maybe didn’t reflect the content of the exhibition properly.

Šelda: There’s talk behind the scenes that you two inherited the project? That the idea for the exhibition was not initiated by you?

Kati: It’s true that the geographical focus was set beforehand, but the thematic concept for the exhibition was developed by us. When Jaanus Samma’s work was acquired, the need emerged to find a context in which to present it. That was in 2015. So the process probably started then, with our director Leevi Haapala thinking about a suitable context. If we could make a collection exhibition, then from what angle to do it?

But since we were working very intensely in 2015 and 2016 with the previous ARS17 exhibition, which was in 2017, then, quite honestly, the other programme was lagging behind. So, the planning of this exhibition did not start actively before the beginning of last year. The curator Eija Aarnio was still working at the collection, and she made the first list of what we have in the collection, based on a geographical rather than a thematic principle, which would have been the usual way to approach an exhibition. But then Eija changed jobs, and Saara Hacklin took over, and in a way inherited the project.

Saara: And then Kati Kivinen became chief curator of the collection, as Arja Miller left for EMMA (Espoo Museum of Modren Art). So the of the idea for the exhibition within the institution are longer there. The curatorial work started last spring with us, but our colleagues on the acquisition board have been buying works, like Flo Kasearu’s Uprising (2015), with the future exhibition in mind.

Flo Kasearu, Uprising, 2015, video, 4 min

Flo Kasearu, Uprising, 2015, Uprising (The Aircraft), 2015, photo: Finnish National Gallery/Pirje Mykkänen

Indrek: There are references to Kiasma’s ‘Faster than History’ exhibition from 2004, which was the last big display of art from the Baltic Sea region. Šelda and I both have to admit that we didn’t see it. But I think any of our colleagues with more experience would start by comparing these two exhibitions. Reading the catalogue, the references to ‘Faster than History’ never go further than just a mention. Is there any kind of continuity between the exhibitions?

Saara: ‘There and Back Again’ is a collection exhibition. ‘Faster than History. A contemporary perspective on the future of art in the Baltic countries, Finland and Russia’ was in the exhibition programme, and very much research-based. So the stories of the exhibitions are quite different.

But it’s true that ‘Faster than History’ was an exhibition that addressed the same geographical region and post-Soviet condition.

Kati: We don’t have too many pieces bought from that exhibition. I myself was working as an assistant for the exhibition when Jari-Pekka Vanhala was curating it. And I have been trying to remember why we didn’t buy more works. We bought Ene-Liis Semper’s video work Untitled (2004), Minna Rainio’s and Mark Robert’s video installation Borderlands (2002-2003), Mikhail Jeleznikov’s animated film Tales on the Marches (2002), and large series of photographs by both Tuukka Kaila and the Blue Noses Group, but I think that was it. I’m not sure why we didn’t acquire more works. Was it just the decision of the board, or were there financial limitations? Our annual budget is not always the same.

In the museum, we operate in five-year cycles. The director changes every five years, and each one has his or her own taste, not only about exhibitions, but in a way also about what the museum should be acquiring. Nordic art, Baltic art or even something from further away. More photography, or more paintings. These changes are sometimes quite visible with different directors.

Talking about acquisitions from the Baltic region, after ‘Faster than History’ there was a rather quiet moment. But we’ve been showing art from the Baltic from time to time. In 2006, Mark Raidpere took part in the ARS06 exhibition; in 2007 we bought Katrina Neiburga’s video installation Solitude (2005) from the Ars Fennica exhibition; and in 2010 we showed Kristina Norman’s project After-War (2009) straight after its acquisition. And recently we’ve also shown works by Tanja Muravskaja and Katja Novitskova, so the connection has not been completely shut down. But there definitely weren’t such conscious acquisitions as in the 1990s, when there was a focus on Baltic and Russian art, especially in the early years of the museum.

Katrīna Neiburga, Solitude, 2005, three-channel video installation, 10:20‘

Šelda: When I look at how the Kiasma collection is put together, and then compare it with national art museums in Estonia and Latvia, your way of collecting seems to resemble the choices of a self-conscious collector rather than what I’m used to understanding as a museum collecting policy. The choices are, of course, professional, but at the same time, Kiasma seems to be more subjective. There doesn’t seem to be the ambition to cover everything, in the sense that the museum is often understood as an institution which builds up an art history narrative with its collection.

Kati: Kiasma buys mostly Finnish art. We acquire seventy to a hundred pieces every year. And around eighty per cent of it is Finnish art. But even there, I would say the collection isn’t completely representative of a decade or a period. The reasons are partly the same as what I’ve already mentioned: the director, and limited funding. And these factors apply even when talking about Finnish art. We do fill-in caps occasionally, usually when we’re aiming for a certain project or working on a solo exhibition by an artist. But the bottom line is that, instead of comprehensive representation, we aim, according to our strategy for collecting practices, for a collection with interesting and high-quality contemporary art, which will be acquired by transcending national and geographical boundaries, but with a special emphasis on art from neighbouring areas. International acquisitions are often linked to the museum’s exhibition profile.

Saara: It’s important for a museum not to act like a private collector who buys what feels good. So I’m rather concerned about your comment. We have a very competent board, consisting of four curators, two outside members, and the director. But I do acknowledge that a collection is always just one interpretation. It tells a story about its time, from a selective point of view, so it’s always missing something.

Tea Tammelaan, Hats from the project Beyond Roles, 1996, mixed media, Collections, photo:Finnish National Gallery/Pirje Mykkänen

Šelda: Our question was partly provocative, of course, but it also comes from the fact that many private collectors approach their collections as museological. The Saatchi Gallery, for example, or Jānis Zuzāns in Latvia, who is in the process of building a private museum.

Indrek Grigor: The exhibition catalogue stresses that ‘There and Back Again’ is a collection exhibition. Am I on the right path if I speculate that the exhibition has grown out of a need to rethink what’s in the collection? The articles in the catalogue quite often refer to the initial principles for collecting that were agreed on when the museum was established. So maybe it’s even more about returning rather than rethinking? You both start your article with Kiasma having the ambition to be a regional museum. Meaning there is no pressure to buy something every now and then, for example from Ai Weiwei.

Saara: A collection exhibition includes the possibility for us to buy new works, as we do buy a lot of works from our own exhibition programme. Most international works are acquired from shows we do here, so the works already have a connection with Finland, and especially with this house. So the international part of the collection doesn’t grow without a relation to the museum and to local audiences.

Our current director Leevi Haapala has been at the museum for a long time, and has also worked with the curator Maaretta Jaukkuri, who was a key figure in the early days of the contemporary art museum. She had very good connections with Baltic countries. So in that sense, ‘There and Back Again’ is a return to those early days. But at the same time, the world has changed, and so has the relationship between Finland and the Baltic countries, as well as the art world in general.

In the early days of the museum, the notion of widening circles appeared. I think people realised quite quickly that when we think about what a contemporary art museum in Finland should or could be, it makes no sense to try to copy the major international museums in centres of the art world.

That said, we have the Pentti Kouri collection, which contains quite a lot of works which would otherwise be beyond our reach.

Daria Melnikova, Room 3. Follow me, 2015, installation, measures variable, Collections, photo: Finnish National Gallery/Pirje Mykkänen

Roma Auškalnyte, Katto | Rooftop, 2017, Kokoelmat | Collections KUVA Kansallisgalleria/Pirje Mykkänen, PHOTO Finnish National Gallery/Pirje Mykkänen

Šelda: Continuing with the topic of collecting. The exhibition is based on the topic of a journey. But what I feel the exhibition lacks is an emphasis by the artworks on a journey in the collection. Neither the catalogue nor the exhibition told that story. Maybe that’s my personal problem. I’ve recently been to quite a few exhibitions which were presented as collection exhibitions, but which did not want to tell the story of the works.

The only story that’s partly revealed in the ‘There and Back Again’ catalogue is Jaan Toomik’s Dancing Home (1995). We learn that his fee from the Museum of Contemporary Art allowed him to buy a camera, which in a way triggered his video performances for which he is now world-famous. For me, these stories are very interesting and important. Maybe not with all the works, but still. Is the telling of these stories consciously avoided?

Saara: That’s an interesting question. One of the reasons might be that we did not think or realise that it would be so interesting. Toomik’s video is a special case. Leevi Haapala had a very vivid memory of its production process for the ARS95 exhibition. But then there are works about which we have only a few lines in a database, and nobody to remember their moment of acquisition. We can guess that certain works were bought because Maaretta Jaukkuri was involved in some project, or visiting exhibitions in the Baltic States.

In the context of the current ‘There and Back Again’ exhibition, for me as a curator, it’s been very interesting to meet artists whose work was bought in the 1990s. In some cases, it was a bit awkward for the artist to be asked about works they made while still studying. But we had a series of good discussions. For example, with Nomeda Urbonienė in Vilnius about her photographic series ‘Two in Periphery’ (1994), which she made together with Elena Valiukaitė and Gintautas Trimakas. The photographs became part of the collection quite coincidentally. They had an exhibition in Helsinki, and even though nobody knew the artists here, the works were bought. That was a beautiful story to hear.

We can emphasise the story behind the work a bit more in the case of commissions. Like, for example, Roma Auškalnytė’s Rooftop (2017). The interview with her about creating the work and what she thinks about being an artist is available on the museum’s YouTube channel and in the mobile exhibition guide, together with a selection of interviews with other artists.

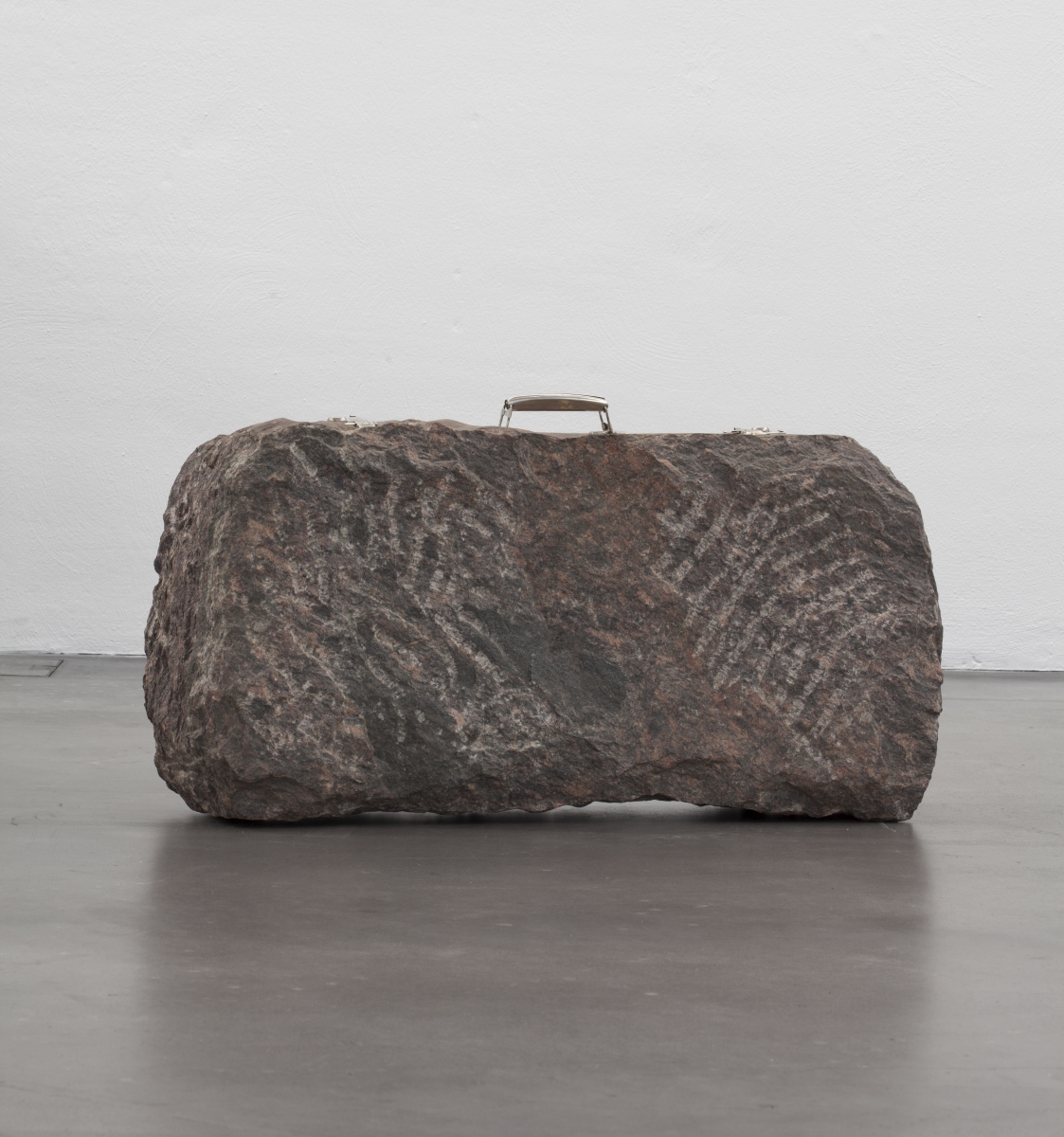

Gediminas Urbonas, Suitcase, 1988, Collections, photo: Finnish National Gallery/Pirje Mykkänen

Jenni Yppärilä, Corner Shop (Ikaalinen), 2012, photo: Finnish National Gallery/Pirje Mykkänen

Jenni Yppärilä, GoodsStation (Tampere), 2013, Corner Shop (Ikaalinen)

2012, Health Centre (Pori) , 2013 photo: Finnish National Gallery/Pirje Mykkänen

Šelda: For example, Daria Melnikova was approached by the Latvian National Art Museum about buying her work Room 3. Follow Me shortly after Kiasma had bought it. And I asked the museum why they took such a long time? The work was first exhibited in 2015. The museum’s answer was that it had just been in a queue. The budget is as it is, and it was just waiting for its moment.

Kati: This also happens here. We plan to buy something, and then some big private collector, or more often a foundation, gets in first. Since the big private collectors in Finland focus mainly on international art, they don’t compete with us so much. But there are big foundations, like, for example, the Saastamoinen Foundation, or the Wihuri Foundation. They often present the most competition for us with acquisitions.

Saara: You may think you missed a chance, but at the same time it’s good for the artist that the piece is in a museum collection. And in some cases, works can be lent too. For example, at the moment we have Roma Auškalnytė’s photograph Titled (2017) in the exhibition, and some of Inga Meldere’s paintings are on loan. But this also has something to do with the challenges presented by materials and the budget.

Indrek: One more point about why we asked for the stories of the works. The exhibition features Tea Tammelaan’s hats from the project ‘Beyond Roles’ (1996). As you have already said, an important part of Kiasma’s acquisition policy is buying from the museum’s own exhibitions. So I was wondering about the importance of her work at the moment it was bought. To be honest, I had never heard of her before. She’s an interior designer, and has works in the design museum and the architecture museum collection in Tallinn, and Tartu Art Museum has a sculpture of hers, which, as somebody who has participated twice in the inventory of the sculpture collection, I should have seen, but I have no recollection of it. So now in this exhibition, I felt that Kiasma was teaching me something about the history of Estonian art. In this context, the notion of Kiasma being a regional collector with a conscious taste started to make sense. For I can’t imagine an exhibition where Tartu Art Museum would ever show the sculpture they have.

Kati: It was very interesting to meet Tea Tammelaan here at the opening. Especially together with Kiasma’s founding director Tuula Arkio. She and Maaretta Jaukkuri had very close connections with St Petersburg in the 1990s, as well as with the Baltic countries, especially with Estonia. They really knew the scene. And Tammelaan was probably important at that time in Estonia, and they picked her up fresh for an exhibition called ‘Dialogues’, focusing on participatory art. That was quite a progressive idea back in 1996.

Tammelaan said that due to having small children she was struggling to find the means to do visual art, and quite soon after the exhibition in Helsinki she left it, and has been concentrating ever since on interior design. We asked ourselves whether it’s right to show the work if she’s not active any more. But it’s a piece in our collection, from a specific time. And the exhibition in which it was featured is still very important in the Finnish context, due to the artists who participated in it, like Minna Heikinaho, Henrietta Lehtonen and Tiina Ketara. I think this context, and the other works which were bought from that exhibition, also raise the importance of Tammelaan’s work.

Alexei Gordin, In Your Head, 2016 / from the series Do not disturb me from doing my art project akryyli kankaalle / acrylic on canvas78 x 98 cm, The Fund of Päivi and Paavo Lipponen, People’s Culture Foundation, photo: Finnish National Gallery/Petri Virtanen

Šelda: Works from the 1990s that nobody knows about are one thing; emerging artists are another, like, for example, Alexei Gordin, whose works were brought to Kiasma before he had received recognition back home in Estonia. Now he’s the latest winner of the Baltic Painters Prize, but you have works from his graduate show in your collection. Again, looking at the national art museums in Latvia and Estonia, they do collect works by quite young artists, but they still go for safe choices. You can be young, but you have to be established. Kiasma seems to be much more open to the wild card, you don’t know whether he will be a one-hit-wonder, or will stay in the art field.

Saara: Alexei Gordin and Alge Julija Kavaliauskaitė were both part of the same MA graduate show at the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki. They were bought by the collection of Päivi and Paavo Lipponen. They have a habit of buying works from graduate shows. The Lipponen collection, in turn, is deposited in Kiasma, and we treat it as part of our collection.

Kati: As I said previously, the collecting policy can also change a bit with the directors’ terms. One director may prefer safe choices, but the next one might be less cautious.

Šelda: Looking at the exhibition, Estonia is obviously represented best, and with the safest choices. Jaanus Samma and Flo Kasearu are at a high point in their careers. In Latvia’s case, I agree with the choices, but would ask why, for example, Krišs Salmanis and some others who have been around for longer than, for example, Daria Melnikova, are not featured. And moving on to Lithuania, except for Mindaugas Navakas, everything makes me scratch my head.

This is not meant as criticism, but the exhibition seems to reflect the inevitable fact that one knows one’s closest neighbours best. And moving further away, the contacts are not so strong any more.

Kati: I’ve been a fan of many Lithuanian artists since the end of the 1990s. But with many of them today, we need to reconsider whether we can afford them. On the other hand, many artists that we already have in the collection, like, for example, Darius Žiūra, are represented by older works.

Roma Auškalnytė is similar to Gordin and Kavaliauskaitė. She’s quite unknown in Lithuania, but while living here in Finland she has gained reasonable recognition. She’s held exhibitions in Vilnius too, but, for example, when we were conducting interviews with other participating Lithuanian artists last year, they were not familiar with her work.

Inga Meldere, Installation view, photo: Finnish National Gallery/Pirje Mykkänen

Inga Meldere, Process, 2017-18, 60 x 50 cm, Collections, photo: Finnish National Gallery/Pirje Mykkänen

Šelda: A Lithuanian artist known in Finland and unknown in Lithuania is a topic Maija Rudovska touches on in her article ‘From Roots to Routes’ in the exhibition catalogue. Diana Tamane, a Latvian-born photographer who studied in Estonia, is a good example of a similar case. She achieved vague recognition in Estonia, but only after her studies at HISK in Belgium did she become really popular in Estonia, and because she became so popular in Estonia, the Latvians suddenly woke up and are trying to incorporate her into the Latvian art scene.

Saara: Yes, Maija Rudovska’s article addressed what we too have observed. Studying abroad is also a popular option for Finnish artists. But at the same time, when you study in England, for example, you might return with excellent practice, but you lack the local network that those who study here can gain. I remember getting to know some new names when doing curatorial work for AV-arkki, the Distribution Centre for Finnish Media Art, and realising that being absent from the local art scene can create really unfair situations. Of course, many of the artists have international careers, so they don’t necessarily need local recognition; but many of them wouldn’t mind the attention, and we as a museum wouldn’t want to miss out.

Šelda: Another question concerning the exhibition is about the particular works you chose. For example, in Inga Meldere’s case, you’ve chosen to exhibit a series of paintings, some of which are in the collection, and some are not. But in Jaanus Samma’s case, you exhibited the videos and displays that are in Kiasma’s collection, but not the pictures and archives which still belong to the artist, nor the balcony, which is in a private collection in Latvia. All the rest I could dismiss, but I really missed the archive. The protocols and stories and letters. It had this character of digging into the material.

How were the decisions made when to show just what’s in the collection and when to add? Was it just a practical decision?

Saara: We also borrowed a photograph from Roma Auškalnytė for the exhibition. And we’ll have to borrow another set of photographs from Anna Reivilä, because our conservators don’t allow us to exhibit photographs for the whole duration of the exhibition. So if you come to the exhibition in the autumn, there will be different stories. This is one practical issue. Inga’s case is a bit different. We wanted to buy new works by her for the collection, and so we planned to commission new paintings for this exhibition. But when we learned the scale of what she’s planning to produce, we realised that we couldn’t afford all of them, so we acquired some of the new paintings. But Inga had prepared the series for this particular space, so it was important to show the whole series.

And in the end, as always, there’s a lack of space. For example, Kristina Norman could very well have been part of the show. But her installation demands three rooms, and that’s a third of the space we have available, which didn’t seem justifiable, especially as her work has been shown before with the ‘It’s a Set-up’ collection exhibition, albeit back in 2010, when Pirkko Siitari was the director. There were similar considerations with Jaanus Samma’s installation. To borrow the other parts of the installation and to build it up in full would have taken a lot of space.

Indrek: I’ve already complimented you on having Tea Tammelaan in the exhibition. Another revelation for me was the dialogues you also created between the artists. Even though at times they seem a bit formal. For example, having Jüri Okas’ prints next to Flo Kasearu’s airplane is a very interesting combination. I can’t imagine an exhibition context in Estonia where you would have a reason to put Okas and Kasearu next to each other. But at the same time, it looks as if the idea for it came from one of Okas’ works having a yellow triangle on it that sort of resembles the shape of a paper airplane.

Jaanus Samma, Marko Raat, A Chairman’s Tale, 2015, Collections, photo: Finnish National Gallery/Pirje Mykkänen

How far was the choice of works featured in the exhibition determined by the design?

Kati: We didn’t consciously put older and newer works together, it was mainly all about the dialogue between the works themselves, like, for example, works by Daria Melnikova and Nomeda Urbonienė, Elena Valiukaitė and Gintautas Trimakas facing each other, creating a rather interesting connection. Or sculptures by Gediminas Urbonas next to a new installation by Roma Auškalnytė might at first sight seem totally different, but on an emotional level there is a connection.

One situation where we very consciously pushed the dialogue was between Jaan Toomik’s Dancing Home (1995) and Karel Koplimets’ ship built out of empty beer cans Case No 13. Waiting for the Ship of Empties (2017). They’re not placed directly next to each other, but the wall between them forms a nice link.

Indrek: Last question. Have there been public discussions about Kiasma’s collecting policy?

Does anybody care?

Kati: Galleries do. They complain that we don’t buy enough [laughing].

Saara: And every now and then there’s a work that raises questions. I guess the most recent well-known case was with Teemu Mäki. There was a big scandal surrounding him, and it provoked strong reactions when it dawned on the public that the work was in the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art. But I think people do feel that the museum and its collection are something for them, and that works are bought with their money, and we are responsible for it. And they’re right. Even though the Finnish National Gallery is no longer solely a state institution, but has been reorganised into a public foundation, our main work is to look after the shared cultural heritage.

But apart from this, is there a more principled public discussion? … Not really. Artists and professionals do, of course, follow what we buy, but they usually have their own interests at heart, like the galleries mentioned.

Kati: And the attention of art critics is first of all on what we show, rather than on what we collect. There’s a lack of in-depth discussion on collection works in the media at large in Finland, so next to feature articles on artists, there just seems to be no space for any deeper discussion. I guess, if we bought something very shocking that provoked some discussion … It will be interesting to see how it is now with Karel Koplimets’ boat.

Karel Koplimets, Case No 13. Waiting for the Ship of Empties, 2017, Collections, photo: Finnish National Gallery/Pirje Mykkänen

Karel Koplimets, Case No 13. Waiting for the Ship of Empties, 2017, Collections, photo: Finnish National Gallery/Pirje Mykkänen