Gymnastics has always seemed a serious enterprise to me. On my way to yoga classes some time ago, I used to regularly pass by a space one floor below where gymnasts trained. Unlike racket sports, which I had always felt quite comfortable with, this type of physical exercise seemed a bit intimidating. I couldn’t help but be reminded of the sports classes I used to attend in school (‘Physical Culture’) where we had to climb a five-and-a-half meter long rope each year as part of the activities, whilst the teacher in charge commented vividly on our successes and failures in the process. Personally, leaping over a bar felt like a much greater challenge to me, though I knew there were other people who were just as nervous when it came to their prospects of climbing a rope, and tried to avoid it at all costs. Sports seem to have the power to bring certain hidden phobias to the foreground. Strict practice can also create extraordinary results, and somewhere in the background of my mind, I have a few fleeting images of previous World Olympics in which Latvian athletes won sporting medals in Gymnastics.

Gymnastics has always seemed a serious enterprise to me. On my way to yoga classes some time ago, I used to regularly pass by a space one floor below where gymnasts trained. Unlike racket sports, which I had always felt quite comfortable with, this type of physical exercise seemed a bit intimidating. I couldn’t help but be reminded of the sports classes I used to attend in school (‘Physical Culture’) where we had to climb a five-and-a-half meter long rope each year as part of the activities, whilst the teacher in charge commented vividly on our successes and failures in the process. Personally, leaping over a bar felt like a much greater challenge to me, though I knew there were other people who were just as nervous when it came to their prospects of climbing a rope, and tried to avoid it at all costs. Sports seem to have the power to bring certain hidden phobias to the foreground. Strict practice can also create extraordinary results, and somewhere in the background of my mind, I have a few fleeting images of previous World Olympics in which Latvian athletes won sporting medals in Gymnastics.

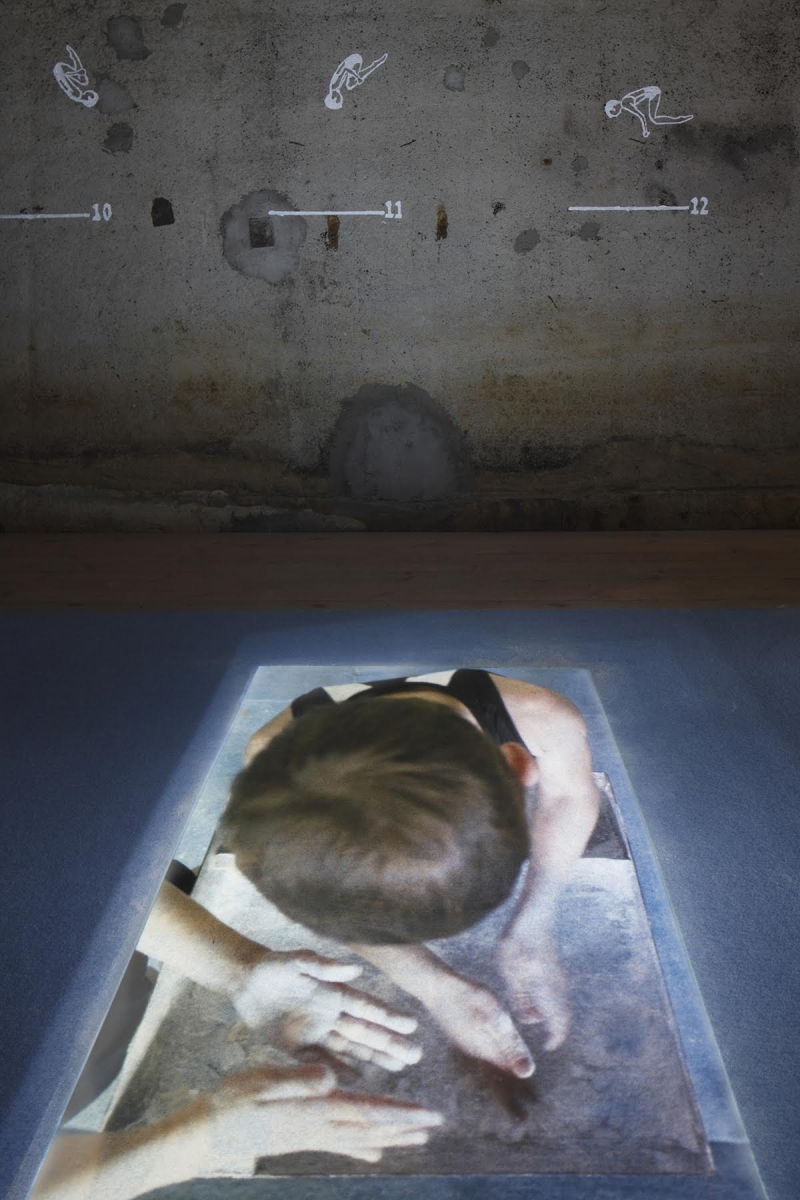

Upon my arrival to the opening of The Exercises, a solo show by Kristaps Epners, the first thing I noticed was a young boy methodically climbing up a dangling rope, and doing it well. Afterwards, I descended into the basement of the exhibition premises to test the clever, optically-illusive, rock-hard mattresses, while observing episodes from athletes’ everyday routines in several video works.

As with many of Kristaps Epners’ pieces, there weren’t any one-set messages here, allowing it to become more about what one read into the work whilst watching it. It was left up to the viewer’s discretion to have thought about Ancient Greek athletes, Soviet heritage, feminist theories and the cult of the body in today’s westernised world (the idealization of being slim and fit!), or to focus on something else entirely.

Epners’ work provided a thought space and a perceptual territory. How people usually view work is largely dependent on the mood they are in. For instance, some people are able to watch full length films at certain moments, and less so at other times. I would suggest it often depends on how clear or occupied a person’s mind is at any given moment. I found his film to be quite time-demanding yet, in a good way, it required the pace of my thoughts to slow down and accept being present in a very physical world where my main focus and full attention had to move onto the human body and its movement. The work seemed to be more about strength and agility of various body parts, the mental subtleties of the process remaining hidden. It feels natural for physical action to eliminate extraneous thoughts, as these thoughts might destroy the rhythm of physical movements. Exercising with a clear head is obviously better – decision, action and completion. Yet, what it takes to be mentally ready for sports is of great interest to me.

In Epners’ video, I could see young adults and children exercising in a certain environment that was aesthetically very distant from the flashy and spectacular sights of uptown sports clubs. Here everything was quite ascetic; there were no contemporary decorations, just an underlying strive for perfection, intense focus and an efficient use of personal will-power. NOASS, its name originating from the biblical story Noah’s Ark, was the perfect place in which to contextualise Epners’ projection of exercises. The stark basement walls of the old floating platform had once been submerged by the dark waters of the River Daugava, with fish cruising through, before it was resurrected some time ago during the early 1990s.

I began to wonder: what if this mythical situation was to happen again, with only one pair of humans allowed into Noah’s Ark, would any of them be athletes? Maybe an artist would be allowed, or would it be a bright mind from the techno hubs of Silicon Valley? A holistic approach of obtaining a stronger mind in a stronger body was a more dominant idea in our ancient Hellenic past. Nowadays, these paths have become more divergent, similar to the disciplines of arts and sports.

A true generalisation could be that most members of the art world are convinced there’s very little in common between the arts and sports. And vice versa, sport circles might think the same, but there is still some ounce of truth in stating this thesis. Both occupations involve completely different activities requiring almost opposite mindsets. So why should anyone even attempt to find a connection or some surprising examples to prove otherwise? Could it be that our century demands that we piece together seemingly split parts, rearranging them together in some still unknown order? With life being a game of opposites, Epners has been looking for this connection already for some time now, using physical sports-related activities as the material and method for his creative output (for instance, in The Run series), often employing his own physical body in the process. The Exercises goes further with the theme of the body, this time involving other practitioners so that the artist could retain his own observational position. Seeing this exhibition reminded me of an earlier work of Epners I had seen where he had filmed a fish tank in a supermarket; the inhabitants of this confined space were doomed to become extinct. Similar to this film, there was a closed, somewhat claustrophobic, feeling retained in the exhibition space—the ship—now populated with humans in various virtually impossible postures.

If both demand deeper levels of focus and attention, what is so different then between arts and sports? Strange as it may seem, people need to be extremely uncreative during sports, performing nothing more than a certain set of algorithms without trying to invent anything new. One becomes an instrument to execute actions precisely, almost automatically, following certain standards. Art, on the other hand, requires a person to do something different, original, even ‘wrong’ by their means or knowledge, in an attempt to find different angles and perspectives. Capturing these physical exercises through the lens of his camera, Epners clearly maintained a selective focus that did not register every event taking place there, but led the viewer along a certain path within the boundaries of his selected events. One knew very little about the diverse personalities of the people he shot. All one knew was that they varied in age, but nonetheless underwent similar experiences that had impacted their lives forever, which had more of a unifying effect, like any school often has, even if it is a school for Gymnastics.

The work seemed more about striving towards perfection through sportive activities despite certain slips and failures not being completely edited out from the scenes. It was about overcoming obstacles and intensely focusing on one activity, no matter what. Despite it being obvious that most of the athletes practicing were mainly male European Caucasians—Latvia is still not quite international, cultural melting-pot, so the gym-reality should not be considered a statement in itself, rather a time capsule of a certain Latvian era in history—the geographic location of the gym did not matter all that much either. Still, something about the image felt strangely generic, as if the practice could have been performed anywhere, as it often happens when observing automatic movements so closely.

One thing that needs to be said is that I clearly felt I was not observing a competition. I was witnessing everyday practice in all its tiresome and mechanical aspects. I was observing the striving for an unknown goal. For each athlete, physical perfection, strength, agility and total control over their bodies probably meant something different, yet valuable.

I also noted the fanatic aspects of the practice, and the obsession with repeating things over and over again. At the same time, the rhythmical repetitive actions really enticed me into the whole image of it. In a way, Epners took risk in showing something already quite aesthetically appealing (most people love watching Gymnastics and other spectacular practices where the limits of the human body can seem non-existent), combining well-shot close-ups with a captivating slow-motion mode. These filmic techniques gave the work a dominating power up until the very moment I started “deconstructing” it into bits and pieces, whereby the magic slowly receded. Despite its emotional and aesthetic experience being incredibly seductive and pleasing to the eye, there was very little irony. I had to question if there was anything more to his use of the aesthetic, or was it simply enough to witness it without actively questioning the process or voicing an opinion on something other than his choice of editing or camera angles? Slow-motion film shows every detail of the action; even the breath of the viewer was slowed down, with the sound of the waves from outside gently supplementing the uncanny acrobatic tricks. What if it all happened in water? Would it change the perception of the work? Would it pull it out of control and make it even more fluid?

I think Kristaps Epners has been treating the material with a certain amount of caution, choosing not to actively invade, upset, exploit or make fun of the material, which if given to another artist, they probably would have done under the circumstances. Although some of the technical subtleties could only be fully appreciated by those more familiar with all the rules of the sport, it was still great to get an insight into their world. Other viewers might only be able to accept the fact that that is the way things function and are supposed to be done in the realm of Gymnastics.

Kristaps Epners’ solo exhibition The Exercises at the NOASS Floating Arts Centre (20.05 – 24.07.2016)

Photography: Ansis Starks