A review of Evita Vasiļjeva’s publication if you can’t, engage (published by kim? Contemporary Art Centre, 2016)

A review of Evita Vasiļjeva’s publication if you can’t, engage (published by kim? Contemporary Art Centre, 2016)

“A book is a piece of architecture. We enter by opening its door, or title page, and move through it by turning the columns of its pages. A book has a body. When we look at the spines of books lined up on the shelf, with our eye tracing the contours of the type, we are reading.”[1]

Digitalisation may have destroyed the typesetter’s profession and the old printing houses, but books continue to hold strong as objects of art per se. We can compare them to buildings, to performances, to exhibitions, to installations and so on, but in the end, they are what they are—an all-encompassing experience of presence, an unhurried and personal way in which I, the viewer, can become familiar with you, the author.

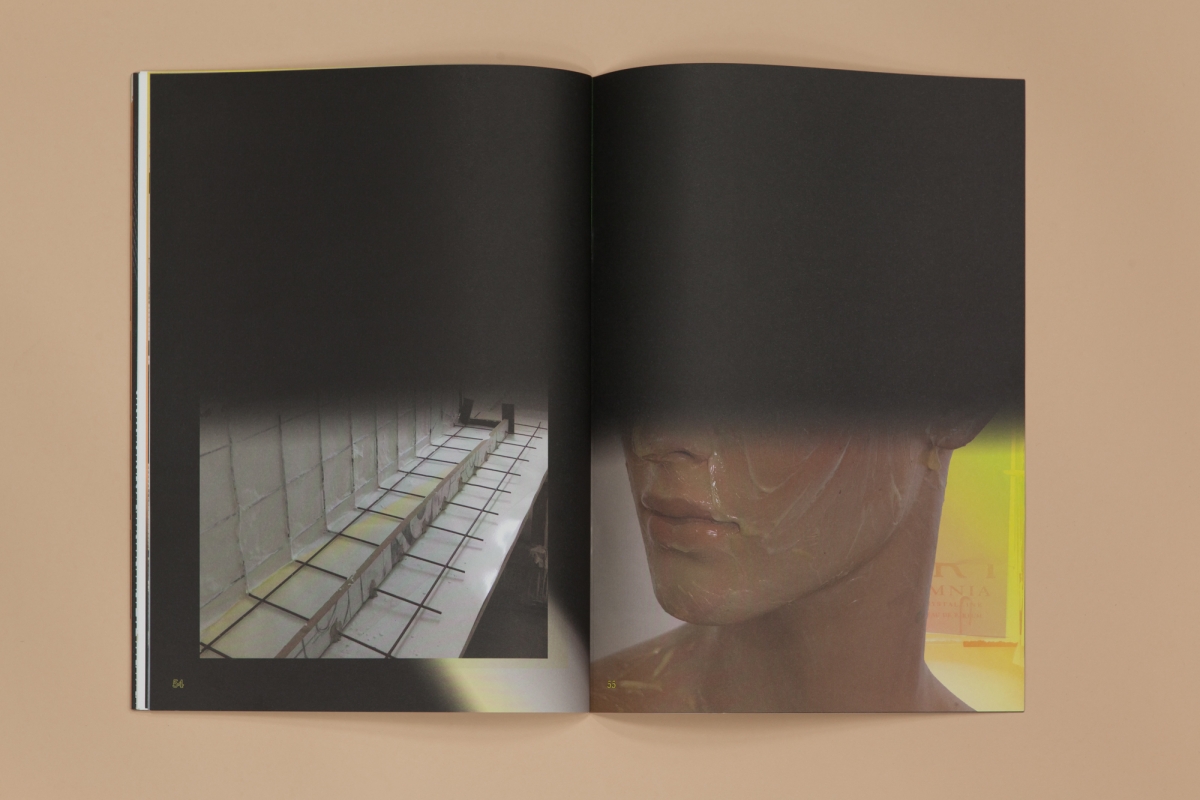

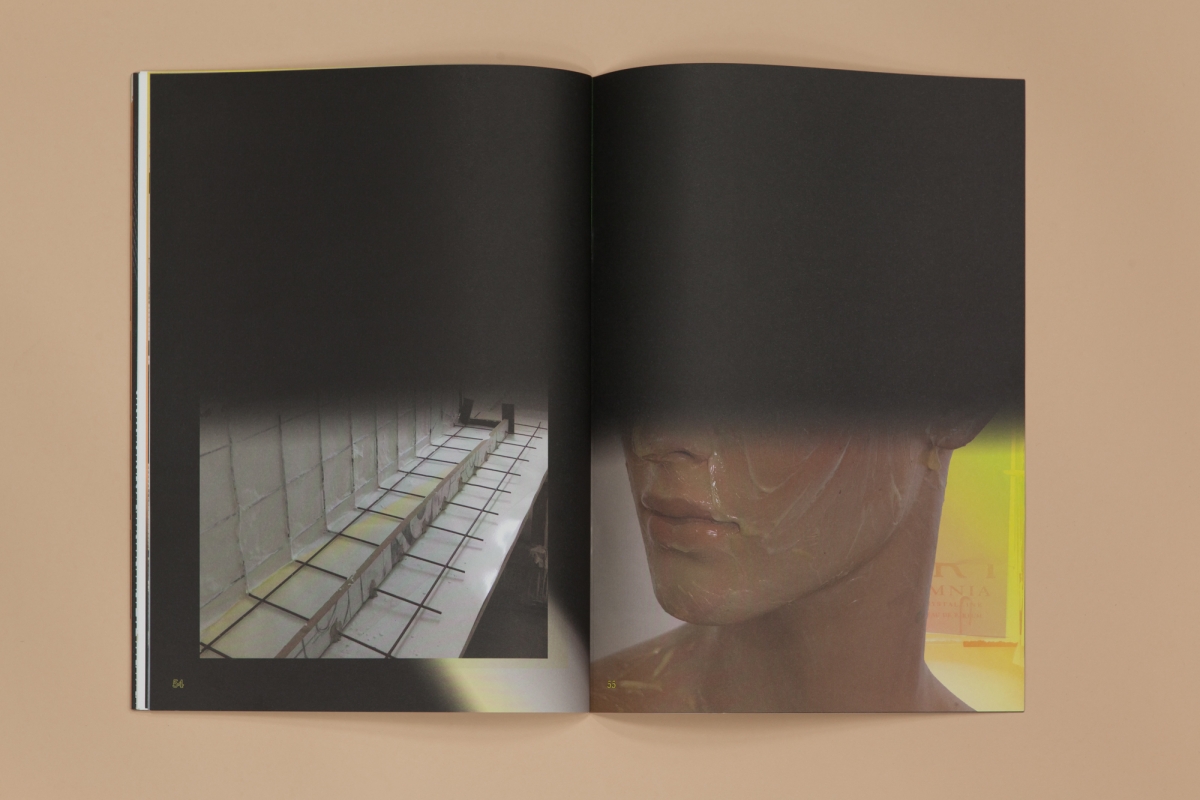

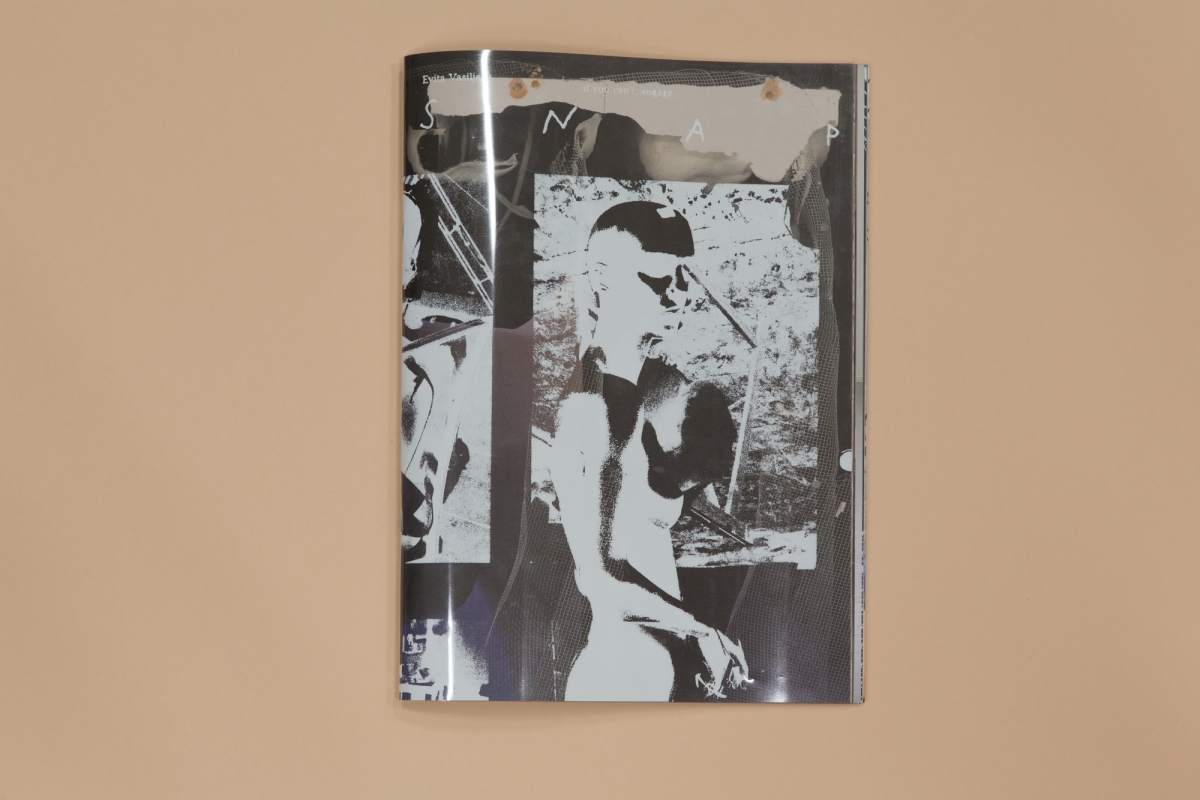

In trying to find parallels with other forms of art, Evita Vasiļjeva’s publication if you can’t, engage most resembles a sculpture. It is like a body in whose intimate zone the experience of art is taking place. I have not seen any of Vasiļjeva’s exhibitions, nor heard her legend; for me, her art is one compact, smooth object manipulated using computer graphics, with an ability to be read from both ends reflecting her creative process over the last few years, whilst documenting her works Models of Now, Then and Maybe (2014), There is no doubt in singularity (2015), Thermodynamic pain (2016) and Untitled (2016).

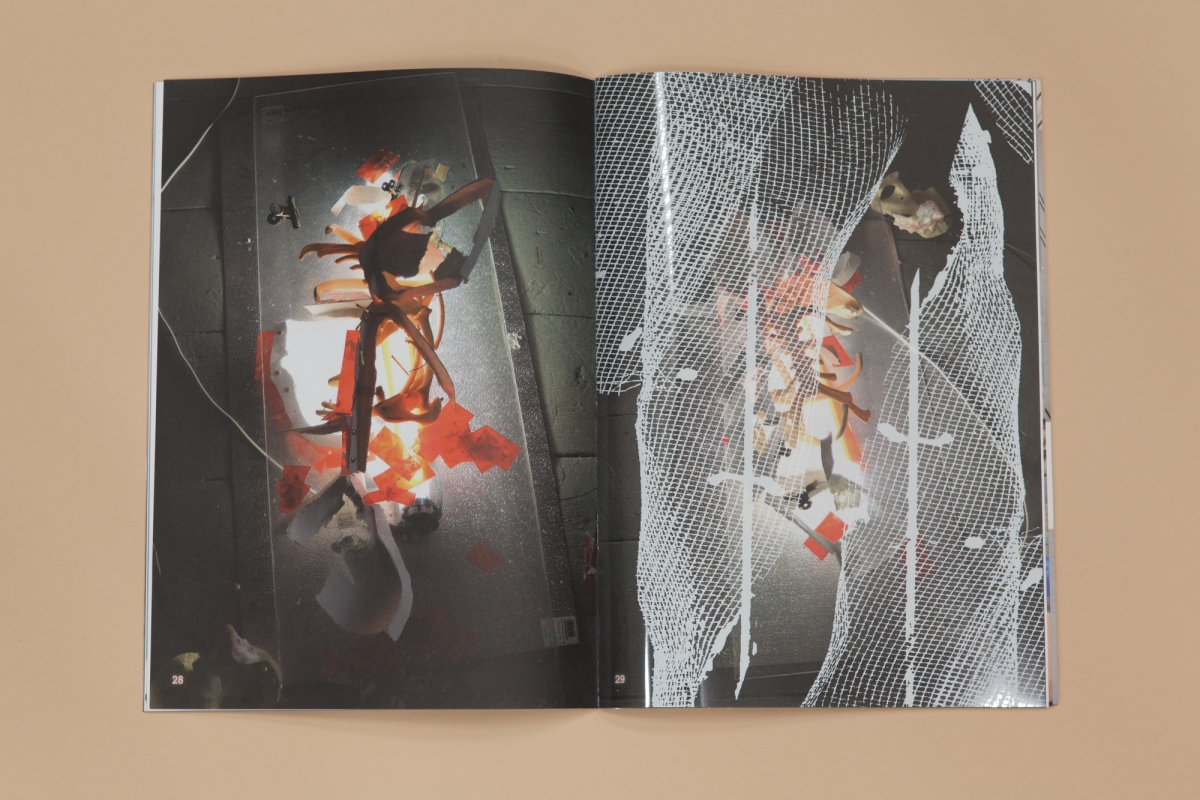

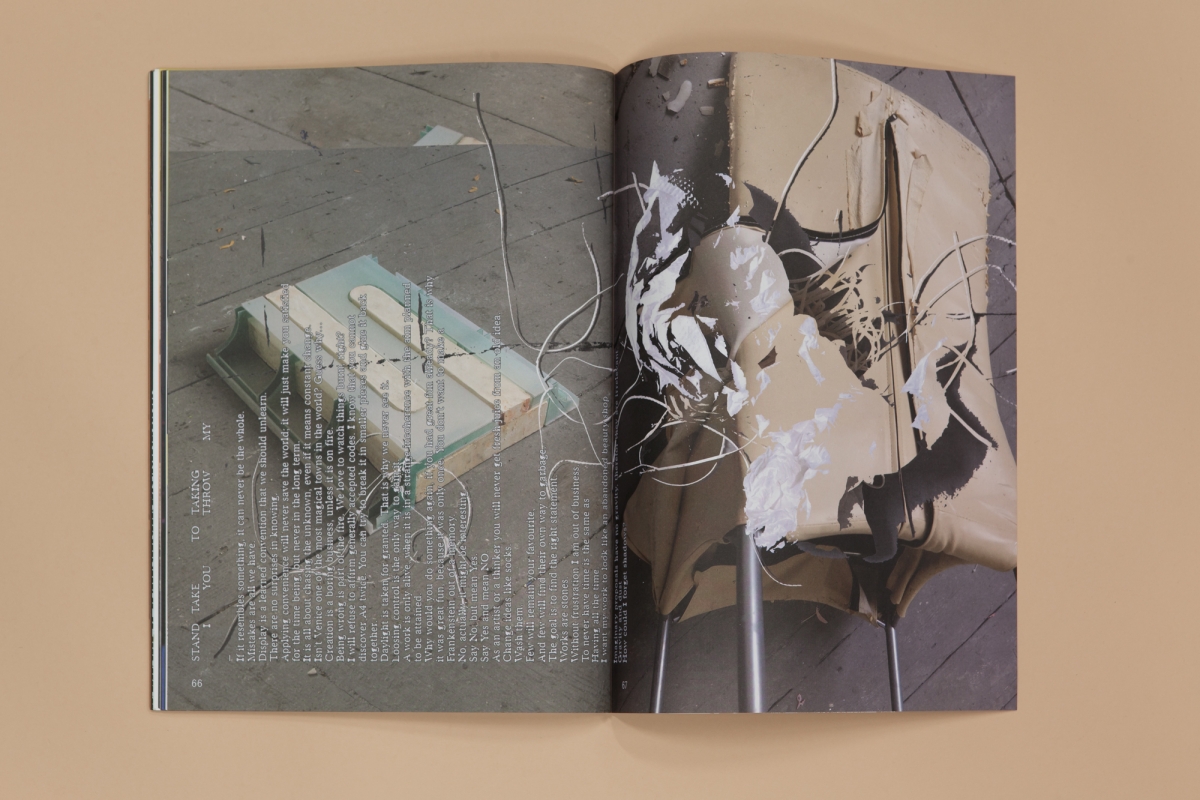

The book arrived in my hands as a vivid, glossy publication that was comfortable to hold; its transparent cover invites the reader to open it up to the first page, to disturb the composition formed by the printed transparent drawing and the photo of an armature underneath it. Following this, the first thing I sensed was the sharp smell of ink. Along with the illustrations, it made me wonder whether this was how the artist’s workshop might have smelled—an intense mix of acetone, cement, soil, glue and lime.

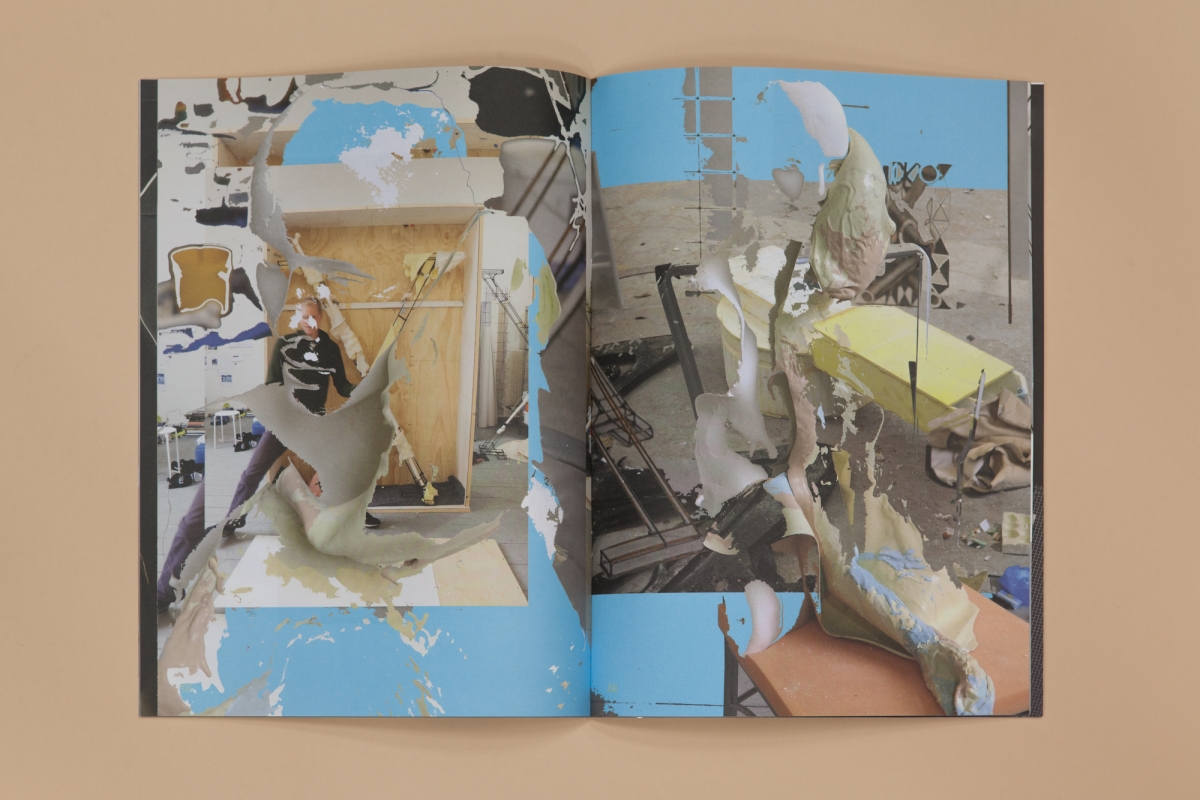

“Untitled, 2016. Compressor, concrete, silicone, cardboard, silicone glue, clay, MDF panels, metal, reinforced steel, paint, tension members, rubber, paper”. Each of the materials used in the installation appear to be listed, their importance emphasised, even with a certain enjoyment. This is Vasiļjeva’s palette; raw construction materials, the sharp and primitive threads with which humans weave their world. Vasiļjeva is interested in the lining—the inside—of this world, which is usually hidden from the eye or is consciously unnoticed. She is attracted to negative space, the repair zone which our eyes are accustomed to excluding from our general impressions. Almost maniacally, she does not believe in the rendered, plastered and polished surface.

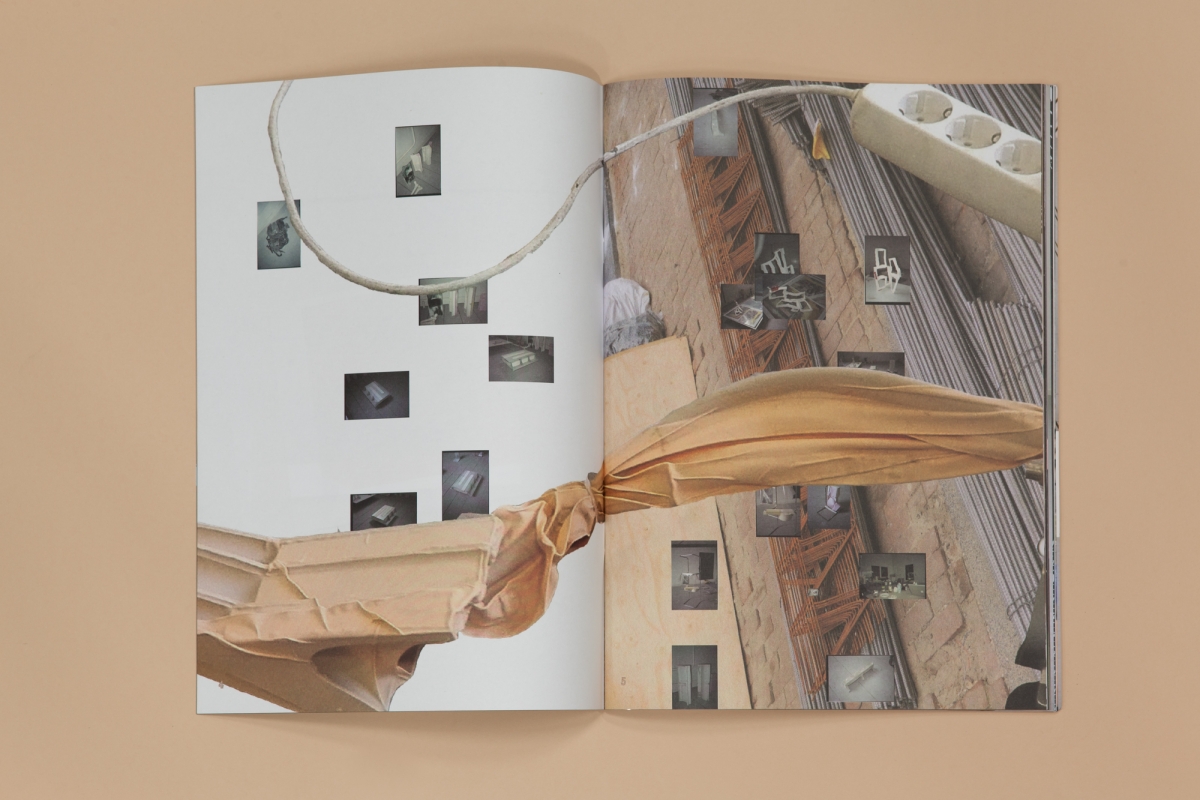

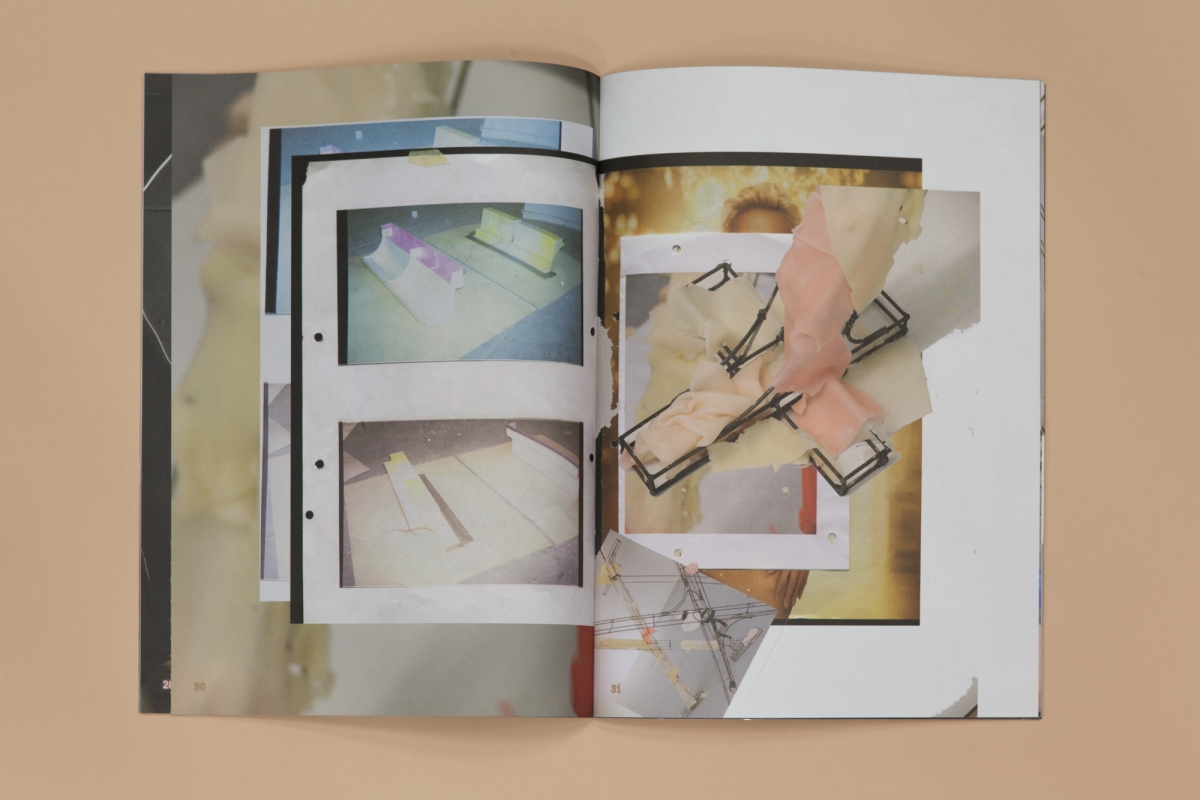

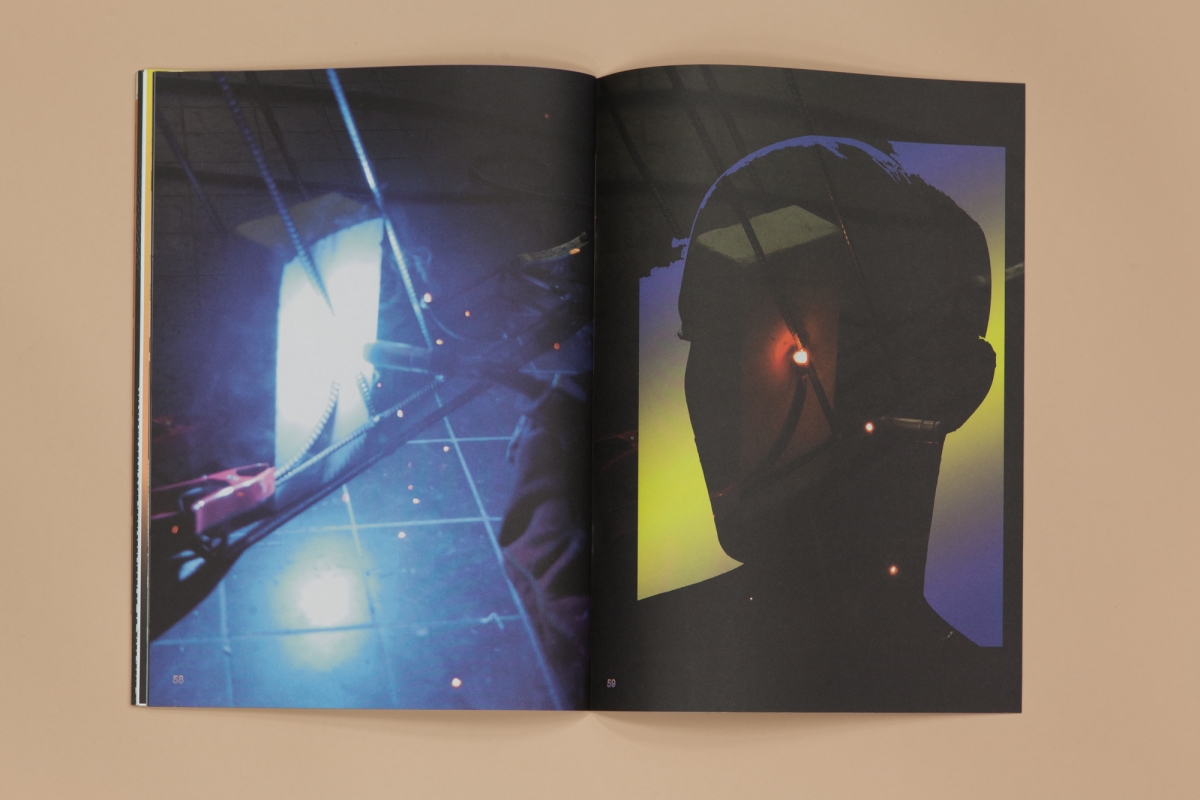

Vasiļjeva synthesises the textures, volumes, light and colour of unfinished armatures and raw materials in a unified aesthetics. In this publication we can see documentary photographs of cheap, temporary constructions, electric installations and colourless, apathetic particleboard nailed to the façade of a house intertwined with the work space, images of tools and exhibition spaces and photos of dismantled mannequins and nude portraits of a woman in her studio—could it be the artist herself or a model? Symbolically, at least, it makes sense for the person inserted through this imperfect process to be the artist herself immersed in her inability to finish a work of art and believe its final form.

Works are stones[2]

Vasiļjeva’s conditions for creation can be described as an unravelling of creative torment—an implosion of expression. The works that she creates are inversions of artworks, reversed forms of what would traditionally be a sculpture, painting or photograph. Instead of constructions or canvases upon which layers of self-expression can be placed, she creates geometric opposites—the dismantling of works, from which layers are removed. In effect, she creates in a negative progression, but the result of the process is not emptiness. She works with indestructible materials (concrete, silicone, cardboard, silicone glue, clay, MDF panels, metal, reinforced steel, paint, tension members, rubber and paper) to make load-bearing structures. In a changing, changeable and even post-factum world susceptible to manipulation, she searches for a foundation—a constant, cemented, eternal basic contour from which she can expand in an opposite direction. She believes (perhaps ironically) in the metal wire and the reinforced concrete to be materials that can be used to build a foundation; that is, if there really is such a thing as a foundation. If one cannot be found, then one must build it themselves. If it cannot be build, then it is for real: “If you can’t, engage”. The only thing that can be real is persistence—the intensity of her participation.

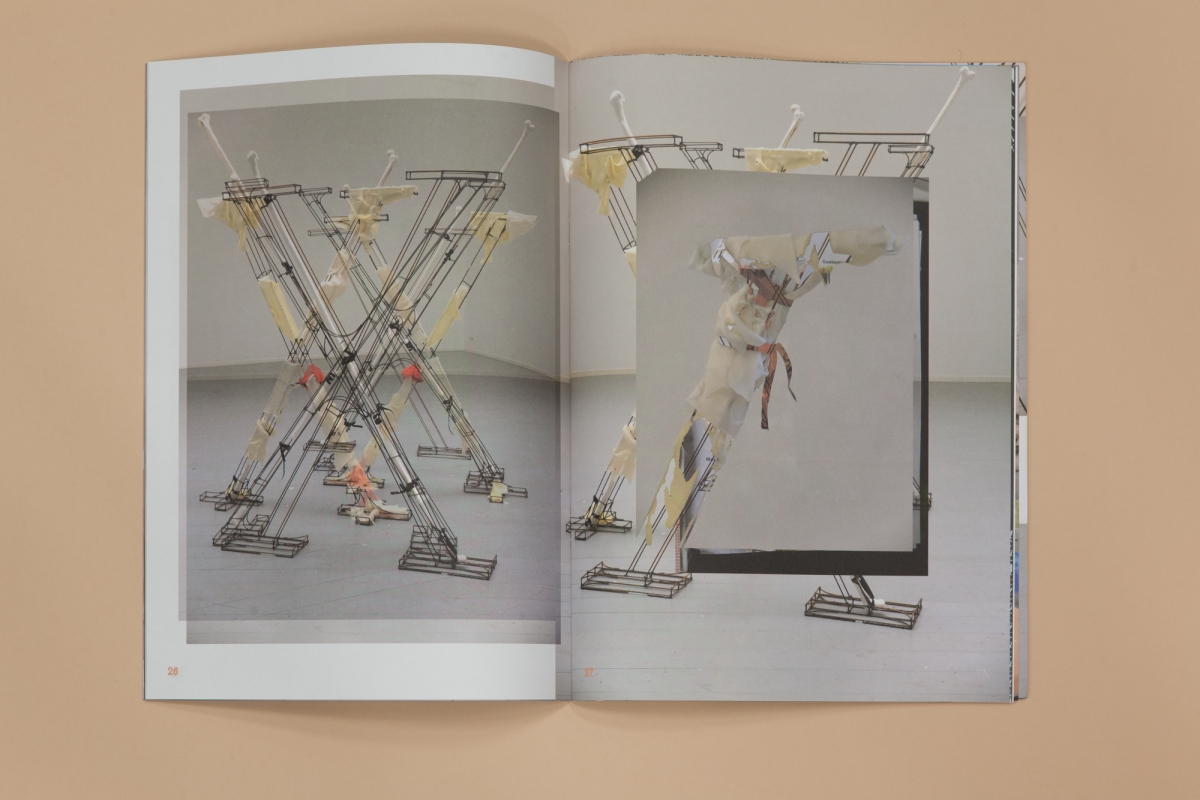

Vasiļjeva not only adheres to this same principle when dealing with space, but also with other substances. The present publication documents attempts to create a person—possibly a lover, a friend or even herself?—in a dismantled form, so that nothing contained is hidden. She also creates a new system of symbols, literally building a typographical sculpture to the letter “X” (in the installation There is no doubt in singularity, 2015), in which the precise geometric structure of this symbol can be seen through the font designer’s artistry clothed with meaning. The letter, used to describe an unknown variable, is strictly portrayed with maximal geometric precision, an oxymoron in itself that demonstrates Vasiļjeva’s approach. It is the way in which she tries to make the unknown known, an idea she continues in her black, closed paintings from the work Thermodynamic pain (2016). In this work, the backsides of the exhibited artwork resemble hermetically-sealed steam boiler covers behind which energy boils but nothing is allowed to escape.

The text in Vasiļjeva’s publication is like a testimony to the artist’s inner conflicts and self-denial: “If it resembles something, it can never be… whole,” “Mistakes are all we have,” “Losing control is the only way to gain it” and so on. She does not believe in novelty or in the confirmation of known, already accepted codes: “I know that you cannot discover A4 twice. You can try to tear it into smaller pieces and glue it back together.” These verities are nothing new or original in and of themselves, but Vasiļjeva manages to turn the condition of ‘creative torment’ into a form and, possibly, take a few steps further towards the understanding of this condition’s productivity.

Being wrong is part of the fire[3]

Vasiļjeva is aware of herself as a creative dismantler–destroyer. She includes herself in the discourse of destruction by the likes of Picasso with his “Every act of creation is first an act of destruction”, Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin with “The passion for destruction is a creative passion, too!”, or Donnie Darko with “Destruction is a form of creation” among many others. Her search for an authentic, truly existing foundational structure brings her closer to the existentialists, who attempt to exist freely and individually in a senseless and uncompromising world. Her building of authenticity occurs through the reverse—revealing what is hidden from the eyes, and the elimination of excess to the point of infinity. Her art is like the process of peeling an onion in which she tries to recognise and legitimise herself.

Presenting one’s failings as art is a fairly common trend in the modern art, because mistakes and capitulation are usually more surprising and provide a more genuine revelation about the world than a finished work of art; in addition, they talk about the darker sides of life and emotions. For Vasiļjeva, however, these sides are not dark and light, good and bad—instead, they are merely visible and invisible.

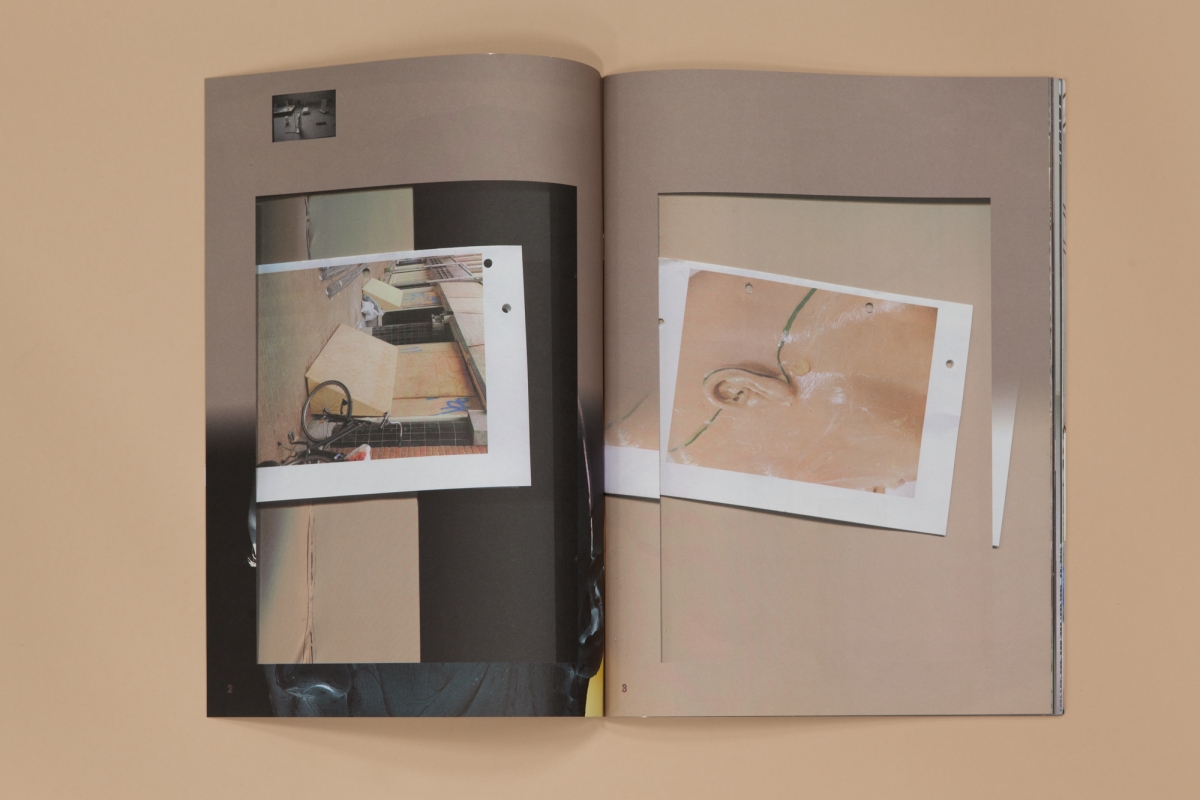

By paging through if you can’t, engage, we too, can reach this ‘other side’ (the backside of the photograph), in which documentary materials and evidence of Vasiļjeva’s exhibitions and creative process are eliminated, dismantled, cut and veiled. In effect, with this publication she and designer Mislav Žugaj compactly reflect what art is for her—a chaotic and instinctive world of ideas within herself, in which all intended and completed works are like loops hooked together and in which each work, each step and each important action is like a hyper-link that associatively and naturally leads to the next idea and concept. What has taken place is not a linear process. Instead, it is a series of cycles layered one on top of the other, allowing all of the previous layers to be seen.

We, the viewers, are at the bottom side of this publication. It is as if we are sitting under a glass table upon which a collage is being layered. We can see all covered-up details, the layering, the noise that has not been covered up and the millimetre pattern of the grid paper, relating to the trellis of an armature. Like cleaning the plaster on a wall, the computer graphics programme coarsely clears spaces, where what remains are spatial shreds of colour similar to the remnants of upper layers that have not been completely removed from the exhibited skeletons of her armatures.

There are many splotches and rough drafts among the layers of a digitally manipulated image, and Vasiļjeva wants us to see them all. A large fragment of explanatory text has also been left, which is more or less superfluous. Just as page numbers are superfluous, maybe this is precisely why it has been left. Instead of being written, the text is a digitalised analogue fragment of text whose background has been erased. Or perhaps it’s a typographical sculpture, and what we see is not really text but an image surrounding a text’s contours?

One of the most significant acts of provocatively destroying an artwork in art history is Robert Rauschenberg’s experiment in which he proved that, by erasing Willem de Kooning’s drawing and framing it, a new work of art was created. Rauschenberg was proving that the destruction of art can, in fact, be a new form for creating culture.

Vasiļjeva does not destroy her works of art; she constantly sits on the border between creating and dismantling. These are simultaneous conditions, like the two poles of a magnet. She is convinced that a work of art can exist only in fluidity: “You will never get fresh juice from an old idea.” No deadline, exhibition or published work is the end-product of the artistic process; nothing finished can be called art. Her conviction regarding this fluidity is held in place by metal wire and cast in concrete.

Photography: Vents Āboltiņš

[1] ‘Typologic: Interactions Between the Intellect and the Senses’, an essay by Chihiro Minato, Tama Art University, 2013.

[2] Quote from Evita Vasiļjeva’s publication if you can’t, engage, 2016.

[3] Quote from Evita Vasiļjeva’s publication if you can’t, engage.