Norman Orro (Music for your plants, EE) performance

Passing through the dunes, we approached the sea. The dawning sun was spreading a cool glow over the water, which looked like a heavy, fluid magma. Walking back through the sparse woods, we encountered a few tourists who were either moving to quiet, empty restaurants or were disappearing in the falling darkness on the way to their rented cottages.

The village of Nida lies on a narrow strip of land surrounded by water between the Baltic Sea and the Curonian Lagoon. Having been a remote and enchanted fishing settlement for centuries, intellectuals only noticed it in the late nineteenth century. Nida artists’ colony was became one of the first formations of its kind in the region of the Baltic Sea. Thomas Mann spent several summers in Nida where he worked on writing his novel Joseph and His Brothers. The poet Walther Heymann returned every summer over a period of thirty years to paint on the Curonian Spit.

Today, the peninsula and the sea area form a cross-over of political agreements, ecological regulations, technological interventions and a touristic economy. On the one hand, it has become a popular holiday destination in summer. On the other, it is a UNESCO listed world heritage site. The vulnerable dunes are a protected part of the Neringa National Park. In 2011, Vilnius Academy of Arts founded the Nida Art Colony. Since then, it has become a venue for artistic, research-based and educational activities. Most importantly, by dedicating its curatorial program to questions related to remoteness, post-tourism and the potentialities of site-specificity, the Colony has opened up to issues of globalism and its effects.

Curators present the programme

Christophe Leclercq (FR) lecture with discussion “To Hybridity… and beyond! Why do we need to reset modernity”

This year, its artistic director Vytautas Michelkevičius introduced an exhibition and an accompanying symposium (the latter co-curated by Neringa Černiauskaitė and Ugnius Gelguda aka Pakui Hardware) on the term “hybridity”, referring to Bruno Latour’s seminal essay from the book We Have Never Been Modern from 1991. The book explores modernity based on the dualism between nature and culture. Latour, both a philosopher and sociologist, argued that there have been two forces at work – one that unifies, and another that purifies – but because of the arising contradiction, modernity has never been able to fulfil its project. In an attempt to reconnect nature and culture, Latour claimed that a clear distinction between the two never even existed, citing phenomena such as global warming or biotechnology that are hybrids of politics, science and fictions as evidence.

The reference for Latour’s investigation is located in the context of recent interest into interconnectivity after “the end of nature”. Later studies have echoed Latour’s theory. For instance, in Thinking like a Mall (2015), philosopher Steven Vogel suggests we stop distinguishing between man-made things and nature as something beyond the human. Vogel goes on to propose that a mall is as natural as a forest. Everything can be viewed as an environment, thus avoiding the idealisation of nature as something distinct. The show nature after nature, curated by Susanne Pfeffer at Fridericianum in Kassel in 2014, also declared the division between nature and culture as “obsolete”, stating: “Nature is us, and everything that surrounds us”, similarly annihilating all conventional distinctions between the synthetic and the organic, man-made and natural, placing all these into the realm of global transformation.

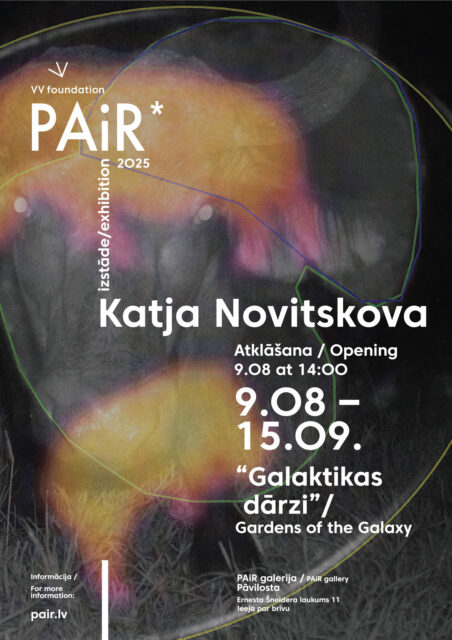

The Curonian Spit presupposes the idea of idyllic nature, which is also the starting point for both the symposium Hybrid Natures and the exhibition Hybrid(…)scapes. The idyllic characteristics cohere with its history of writers and artists looking for retreat, and escape in the natural simplicity of the sand-dune spit. Its contemporary tourist industry similarly pushes advertisements of such sites as incredibly picturesque venues. Instead of believing these myths of nature’s purity, the exhibition and symposium’s curators treat the Spit as a hybrid par excellence; as one can read in the announcement of the exhibition, “its body consists of both nature and culture, which has been using technology for centuries to plant forests and shape the terrain, jointed by underwater hybrid creatures generating the energy for conce(rn)(trate)s for capital and politics”. Here, hybridity serves less as an analytical tool, even if suitable for such purpose, but rather as a tool for effectively sensing a contemporary order of connectivity that allows for taking different origins of power and modes of distribution into account. The approach thus aims at reflecting such geographies as sites of politics.

Valentinas Klimašauskas (LT) Screening and discussion “A Theory of the Plankton”

One of the symposium’s very first contributions was that of curator and author Valentinas Klimašauskas who presented a collaborative film production called A Theory of the Plankton (2016). In aquatic biology, the paradox of plankton states that limited resources enable the co-existence of a diversity of plankton species and even the emergence of new hybrids. Consequently, it seems to contradict the Darwinist evolutionary concept of survival of the fittest. Klimašauskas turns his attention to the co-existence of syntax, materials, humans and space as content whirled up by the algorithms of the Internet, while introducing the possibility of multiple perspectives like those of a DNA or a fossil. This extension is in line with Latour’s later concept on actants asserting agency to human and non-human actors. The film formally relies on intense layering of frames, short videos and gifs – thus creating a notion for contingency – while opening these up to metaphorical and political spaces through spoken text pieces (written by Klimašauskas).

Having in mind technocapitalist investment in artificial intelligence, one can ask whether the creation of artificial matter could entirely replace reality. Such a scenario, drawn by accelerationism and transhumanism, though showing fatalistic traits, has been a logical continuance of the concept of hybridity and poses questions as to what forms of selves would have to be invented. Artist Viktor Timofeev presented Proxyah, v2 (2015) – a work that evolves in the format of a video game: The steps that a player makes to get out of a room are counted. When the player finally succeeds in exiting the room, the number of steps needed to escape form the basis of a sort of magic generator process that creates an island in a unique way. Even if a sense of helplessness arises, an algorithm suggests the controllability of the situation. Timofeev also presented a demo version of another video game belonging to a project with the overall title Sazarus. Here, every peek into a landscape is answered with the construction of a fence. These built environments are not based on problem/solution rationalisation, but enforce mechanisms anticipated by autonomous structures. The players are involved in complicated games where sometimes, they unwillingly trigger modifications, or are moving towards infinite procedures without any resolution at the end. The player caught in the system, eventually becomes its maintainer.

Later on at the first evening, Norman Orro contributed with an audio-visual sound performance, part of an ongoing sound-art project, Music for your plants, he began in 2010. The track mixes digital beats and real sounds, evolving around a vision of a hyper-natural and hyper-social environment where plants only exist as digital allusions. The composition has some archaic traits – like collective gathering and unbundled energy – that anticipate a new social order based on the clustering of organic and non-organic material. The sounds we associate with the real are, in fact, the results of the exploration of the exotic and mythical other in a digitalised reality. Unexpected pathos out of such a new mythical order shines through, though for Orro such conceptualisations of social structures are more like speculations, than political laments. The performance was accompanied by visuals of hybrid human-nature environments, as a sleek living room setting with a monitor. In it, one could see a woman touching her car, or a man on X-Factor mimicking the sounds of nature.

Kira O’Reilly artist’s walk/performance/talk “Unbecoming Sea”

Kira O’Reilly artist’s walk/performance/talk “Unbecoming Sea”

Far away from digital imagery, Kira O’Reilly’s performance Unbecoming sea (2016) was a nexus between awkwardness and 1980s glamour where an affected body was suggesting mourning for inexplicable loss. After reading a radically fragmented associative text, based on technoid vocabulary, O’Reilly headed toward the shore. On the halfway, she put on a green lamella swimsuit and red pumps. Holding branches in both hands, she silently continued her walk into the water until she had almost disappeared under the surface. Her introverted practice accommodated feelings of embarrassment and longing although, foremost, it turned the attention to the vulnerability of the body.

Thus, the symposium Hybrid Natures not only featured contributions that dealt with Latour’s concept, but developed multiple points for further consideration. The same is true for the exhibition Hybrid(…)scapes, curated solely by Vytautas Michelkevičius, which encompasses works by eight artists and artistic duos, all of whom have been previous residents at the art colony. It focuses on scenarios that examine non-avoidable developments and invite artists to develop scenarios of resulting future. As such, Pakui Hardware’s Get the Freeze Habit, (2016) uses a refrigerator – the type of white box that one finds in the streets in summer used for selling ice-cream – filled with different ice shapes coloured with Hawaiian spirulina or Curonian Lagoon algae. Pakui Hardware has chosen ingredients used by the food industry, which has artificially optimized them while branding as closest to natural products. The work makes us aware of how naïve our understanding of nature is, where synthetic biology has already predefined the future.

16mm film screening “In The Travellers’ Heart” (20 min) by Distruktur (BR/DE)

Hybrid(…)scapes, exhibition view. Marika Troili, Offshore / C-true, 2016. 10 pairs of bookends made of unfired clay from the Curonian Lagoon.

Hybrid(…)scapes, exhibition view, VAA Nida Art Colony, 2016

For its greater part, the works presented at Hybrid(…)scapes avoid examining the change of socio-political conditions under the influence of rapid technological development. The film In The Traveller’s Heart (2016) by Distruktur (Melissa Dullius and Gustavo Jahn) pays homage to nomadic figures and phenomena, and their intimate relationship to nature; shot on a 16mm film, it introduces a technique, opposite to the high-tech materials and aesthetics, to show longing and the emergence of non-verbal expression as a way to design its own symbols.

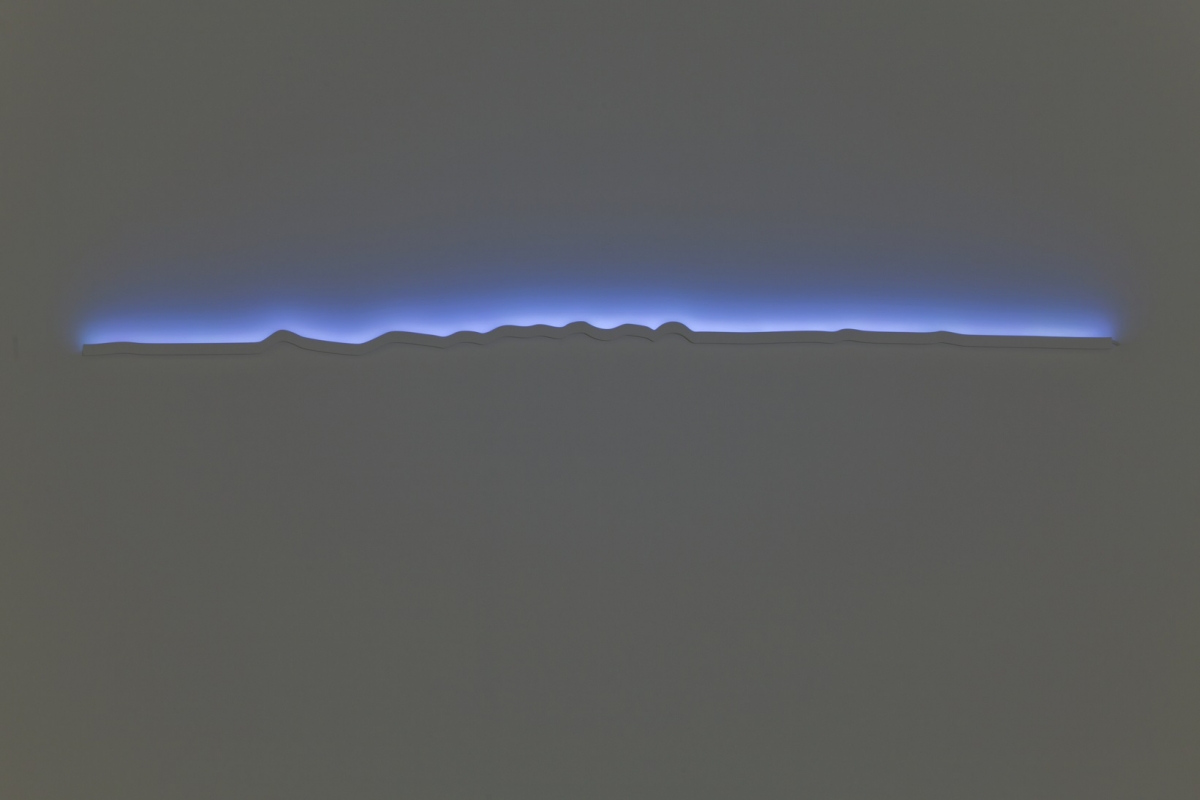

Some other artists formally chose a rather technoid approach to make aware of the complexity emerging from the hybrid nature of objects and phenomena. Taavi Suisalu’s installation May I have your attention (2016) translates and amplifies the soundscape of the wind within the exhibition space. The wind forms the dunes, trees, and even the shape of the Kurėnas, a boat that was once prevalent in the lagoon. The invisible sound suddenly gains material quality through the visitor’s body, that either activates or distorts the sound. In Liddy Scheffknecht’s work Vanishing Line (2016), the border between Lithuania and Russia’s Kaliningrad Oblast turns through a solar powered camera and RGB-LEDs into a beautiful glow line of shimmering colours. While it is aesthetically fascinating, it almost fully absorbs the idealist tendencies of technology.

The emergence of hybrids is permeated by coincidence and contingency. At the entrance is Marika Trolli’s installation Offshore/ C-true (2016). On a black curtain that partitions the space, Trolli has attached ten quotes about the future from the last pages of non-fiction books. These are accompanied by printouts of 1% of the entities appearing in the Panama Papers open database, and by 10 pairs of bookends made out of unfired clay from the Curonian Spit. How do these textual pieces relate to each other? The exact numbers enlarge the contingency at stake within the attempt to rationalise material that has already been reduced to information, or data. The heavy curtain looks, in its theatrical manner, rather over-stated; all it reveals is our wish to make sense out of the situation – and an implied impossibility, of being unable to do that.

Hybrid(…)scapes, exhibition view. Franziska Nast, from the series My favorite Ladies, 2016. PVC banner printing, adhesive foil characters, size varies, up to 7 m height. In the background: Taavi Suisalu, May I Have Your Attention, 2016. Field recordings, ultrasonic speakers, embedded computer, motion sensor, sound absorbers, kapa

Marika Troili, Offshore / C-true, 2016. Printouts of 1% of the entities appearing in the Panama Papers open database, ink, sunfoil, paper and Franziska Nast, Night Flight, 2016. Graphite chalk, copy paper, chinese rice paper, 140×170 cm

Liddy Scheffknecht, Vanishing Line, (sunny, blue sky), 2016. Solar powered camera, RGB-LEDs, embedded computer, wood, acrylic paint. Dimensions variable.

prof. Artūras Baziukas-Razinkovas (LT) lecture „Curonian spit: metamorphosis in between the sea and the lagoon, nature and society“

Jurga Daubaraitė & Jonas Žukauskas (LT) Stratigraphy Of Mind, Core Samples From The Baltic Pavilion in Venice Architecture Biennale

Kuai Shen (EC/DE) Lecture + Beach/Forest Expedition “Enter the colony: the 3 portals into the world of ants”

Photo reportage from the exhibition ‘Hybrid(…)scapes’ at Nida Art Colony

Protography: Andrej Vasilenko, Nida Art Colony