On Rasa Jansone’s personal exhibition “The Fog of Feeding” (Riga Art Space, 04.10-26.10.2014) and “To Art a Woman” (Art Academy of Latvia, 02.10.-24.10.2014, Curator: Elīna Ģibiete)

“Wait, do we have to rape them all?” – these were the words by separatists in Luhansk directed at the women who choose to spend their free time away from their home fireplace, instead of sewing cross stitches and baking pies. At the start of November, a video announcement was published in which separatist fighters promised to imprison any woman found spending time in cafés and bars, because such attractions divert a woman away from her fundamental duties of raising children and caring for her family. It doesn’t even seem important whether these obscurantist restrictions will be implemented with real prison sentences, the very existence of such thinking in a country that is a near neighbour seems odious. A few days later, the Republic of Latvia’s Foreign Minister Edgars Rinkēvičs came out with an announcement concerning his homosexual orientation, which precipitated a positive stream of comments from liberally minded members of the population, who admitted the politician’s declaration to be a significant step on the road towards more tolerant and democratic society. The simultaneousness of both announcements highlights those extremes between which inhabitants of the Post-Soviet space have to coexist and ascertain their – so to say – gender identity. No matter how much one would like to think that since regaining independence we are moving towards a more humane society, such cases remind of the 50 year break from values of liberalism and tolerance in Eastern Europe.

The aforementioned events couldn’t not come to mind to me as evidence of the ideological contrasts of our cultural space, while writing and thinking about two exhibitions which highlighted or tried to take on gender issues – “The Fog of Feeding” by Rasa Jansone and “To Art a Woman” , a group exhibition organised by the students and lecturers from the Art Academy of Latvia. The central thematic motif postulated in both exhibitions was the world of woman, and they sought to cognize femininity in the social reality of latter day at the same time adopting a slightly distanced observer’s position and humble attitude towards these issues, that is without venturing into the extremes and provocations characteristic of classical feminist interventions in the West and to what art and feminism researcher Jo Anna Isaak silently termed as “the revolutionary power of women’s laughter”. Typical forms of expression for socially marginalised groups as parody, exaggerations and deconstruction are not present in either exhibition, instead of laughter, viewers are offered peaceful artistic gestures and meditative, serious moods. With this, I might as well conclude the list of shared traits, because the results are quite different in terms of the scale of their artistic execution and understanding.

In the exhibition “The Fog of Feeding”, the artist has painted mothers or, as referred in the title of the exhibition, women who had been breastfeeding. Not without reason, Rasa Jansone’s name has cropped up previously in relation to manifestations of feminism in Latvian art. In her previous exhibitions, she has also sought to depict the feeling and experience of a woman’s world, as well as reflected on how gender differentiation defines us as personalities, dictates our daily and mutual relations; for example, in the exhibition “Everyday Masculinity”( 2012, Mūkusala Art Salon). In her works, Rasa Jansone strives to dismantle traditional gender stereotypes and a viewpoint, based on a strict division of gender roles, and this process is lightly ironic and playful (as American philosopher and important gender theoretician Judith Butler sagely quipped, “to deconstruct is not to demolish”). The artist’s position is expressed through her sensually vibrant images, in which she neither resorts to naked demagogy nor subordinates artistic content to the ideologyl. The magic of Rasa Jansone’s works manifests itself through her ability to capture those moments and turn a verbal idea into a visual metaphor; it is a semi-dream-like or foggy state, a combination of a murky mystery and a clear narrative. Various allusions to the condition of a child and childhood motifs grant Jansone’s art a psychoanalytical bent, and one is also inclined to interpret “The Fog of Feeding” as a “project” of self-discovery, although other women are exclusively portrayed. With the title of the exhibition, the artist emphasises the particular state in which a woman finds herself during the period of pregnancy – breastfeeding and child rearing. No matter how biologically natural and socially acceptable this state seems to be, it nevertheless creates a certain barrier between a mother and the rest of the world, which the artist expresses through the metaphor of fog.

In visual art, maternity is a relatively archetypical theme; for many centuries, the role of the mother has been emphasised as a woman’s main social duty towards society. With the appearance of the first independent female artists at the turn of the past century, through their works narrative motifs also enter art which allude to the conflict between the identities of the woman-artist and the woman-mother. For example, it is vividly depicted in the graphic works of Käthe Kollwitz, which is confirmed by her diaries and letters from the period – at the start of the 20th century, a creative career seemed incompatible with bringing up children. During the century that separates the lives and works of Käthe Kollwitz and Rasa Jansone, many positive changes have occurred in public attitudes towards a woman’s reproductive rights and their importance to the life of a woman, but a certain confusion still exists in the woman-social life-child relationship. In other words, a masculine identity is still powerfully attributed to focusing on a career, even though no such divide exists in legislative norms. This contradiction does not exist in Rasa Jansone’s paintings – in her portraits, motherhood is revealed to be a spiritual, dematerialized state of the mind and soul. Only women’s faces are painted, creating an intimate close-up impression characteristic of large-format scales, accompanied by the power of a psychological vibration. Jansone succeeds in avoiding the pathos that goes with praise of child-rearing duties; instead, her works prompt one to comprehend and decipher the deeper essence of this state. In her works in “The Fog of Feeding”, motherhood is depicted as one of the most intensive spiritual experiences that one can undergo – in my opinion, it is also a very subtle response to that section of society, which trivialises this experience as “a woman’s natural duty” and manipulates child rearing as a technical demographic instrument or justification for subjugating women and exiling them to the hearth.

A much more confused scene was on view at the “To Art a Woman” exhibition, which lacked a rigid conceptual frame, if one discounts generalisations about a woman’s role in society and career opportunities, etc. The exhibition overview stated that it was being organised under the auspices of the “PROGRESS programme of the Society Integration Foundation project “Gender equality in economic decision making – tool to promote economic competitiveness and equality” and that the exhibition is the research work of a group of artists, whose task is finding answers to the question of why Latvian women rarely hold leading positions (the glass ceiling effect) and why, in the artists’ opinion, disruptive factors exist which preclude women from attaining higher career achievements. Maybe that root of the exhibition’s failure is its positioning as the result of research, which is a typical trait of “project writing culture” – attempts to bureaucratize art and judge it according to the principles of other less creative fields. Unlike the “The Fog of Feeding”, the viewpoint of the exhibition “To Art a Woman” is neither feminist nor based on gender studies; even if the organisers of the exhibition fervently wanted this to be the case and mentioned this in launching the exhibition. Instead, in all probability it expounds tittle-tattle that is wide of the mark about the theme of femininity, which ignores broader manifestations of these ideas in history and theory. With this, I do not wish to state that an exhibition should necessarily illustrate specific feminist theories – not at all, and nor does this occur in Rasa Jansone’s exhibition, but I am nevertheless inclined to evaluate “The Fog of Feeding” as a much more successful manifestation of femininity. It is very possible that the varying qualities determined the relationships of the exhibition’s organisers with “the issue of women” – in Rasa Jansone’s case, her natural and long-standing interest in the subject ensured a successful and convincing result, whereas the theme considered in the works in “To Art a Woman” is artificially injected into both the exhibition participants and the curator herself. As a result, a range of works have been created that demonstrate a lack of an in-depth understanding of the role and experience of a woman in society – instead, there are quite superficial, subjective and not overly interesting judgments on the subject of femininity, which are unlikely to engender clarity on gender inequality in the labour market. Of course, in order to create a profound, considered or otherwise resonant and meaningful work of art, it is not obligatory to draw on intellectual knowledge directly, but the failure to apply critical thinking in an exhibition dedicated to social issues is a serious deficiency.

In the majority of the works in the exhibition “To Art a Woman”, the form and technological execution do not correspond to the ideas expressed in the title or annotation; they exist detached from one another and do not form any visible connection. This prompts one to suspect that the artists’ “studies” are dominated by coincidences and spontaneous associations, which would be more appropriately suited to an exhibition dedicated to a less important subject. However, against the overall background, there are a few works that stand out, in which this carelessness has been overcome – one should definitely highlight Ingūna Audere’s work “Witches Are Burned in All Ages”, in whose burned sacks the artist has managed to a broad field of connotations. The successful relations between the work’s laconic format and multi-layered message generated a pleasant contrast to the other works in the exhibition, which are dominated by polarity, binariness and emphasis on the division “feminine/masculine”. Sensing this, one is reminded of Jacques Derrida’s several decades’ old theories of deconstruction, in which it is emphasised that such oppositions invariably also include hierarchical relations between the opposing masses. Thinking based on polar opposites in gender issues has been sharply criticised by many Western researchers into feminism such as Luce Irigaray who believed that one of the most important tasks of feminism is to overcome such thinking – in the Western tradition, binary oppositions have offered women markedly negative properties. Deliberately or by accident, bipolarity is also emphasised by the exhibition’s overall visual impression, which is also completely monochrome. Regardless of the medium used, compositions executed in black and white tones dominate. Unfortunately, black and white thinking also manifests itself in the artists’ written comments such as those of Kristaps Zariņš, who uses somewhat incorrect terms like “healthy thinking” or “traditionalist”, and Gundega Strautmane, who expresses a disconcertingly conservative view of gender roles. However, it is possible that these very works conceal answers to the questions posed by the Society Integration Foundation.

Are there artists in Latvia who unequivocally work from a feminist perspective? It seems that the position that art is a transcendental, almost godly activity, in which such trivial preconditions as gender are irrelevant, is more popular. Therefore, there is no need to create and appraise art from this position. However, no matter how convenient, such a position is nevertheless unjustified – we are social beings and, as the examples from political life mentioned at the start of the article show, gender issues remain an ideologically significant instrument for the manipulation of the masses. Not only is there no harm in more active reflection on these issues, but it may also serve to help one avoid becoming a victim of propaganda – one should not forget that art can also be co-opted under conditions of democracy and ostensible gender equality.

Exhibition view of Rasa Jansone’s personal exhibition “The Fog of Feeding”:

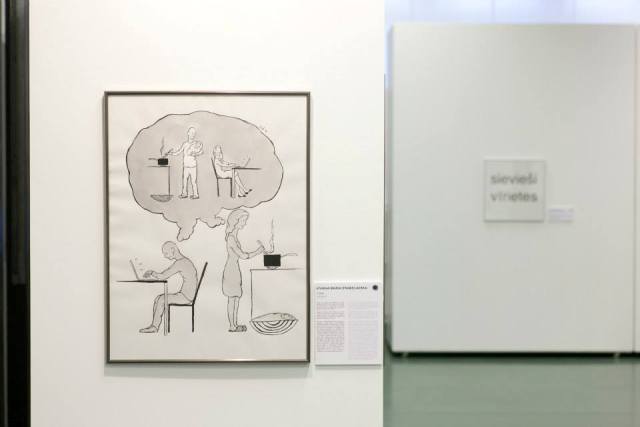

Exhibition view from “To Art a Woman” exhibition at Art Academy of Latvia: