In her latest exhibition titled Bust at Si:said gallery (Klaipėda, Lithuania), Vilnius-based multi-media artist, Dalia Mikonytė, invites the viewer to meditate on, or rather to celebrate, themes of bodily fragility, increasingly elusive boundaries between technology and human embodiment, as well as the relation between illness, convalescence, death and creativity through her series of wall-drawings, photographs and a video projection accompanied by a soundtrack (music and vocals: Rūta Mur, lyrics: Lina Simutytė).

I should perhaps begin my review by mentioning a recent interview in which Mikonytė made an interesting statement that has fed the rationale behind my interpretation of her work here. The interview described her creative process which, among other things, has involved her submitting her body to photogrammetry and medical scanning. Mikonytė noted that when she experimented with these techniques, she sometimes felt utterly overwhelmed and momentarily lost sense of tangible boundaries between her body’s ownness and the alien, intrusive dimension of technology. She claimed that in the process “one becomes a veritable cyborg”, and, to express what this momentary loss of boundaries feels like, added a line from Nietzsche that, of course, every young artist prone to performative exaggerations is wont of quoting: “If you gaze long into the abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you”.[1]

When engaging with Mikonytė’s artwork, there was another of Nietzsche’s statements that immediately came to mind, namely his creative injunction to turn ourselves into the work of art. Now too often this injunction has been treated as a sort of middle-class narcissist credo. However, what one often misses is that such a creative act on the self, to which Nietzsche exhorts us, far from being an expression of bourgeois individualism, implies, on the contrary, jettisoning what Nietzsche calls a phantom ego.[2] Turning oneself into the work of art, then, requires disowning one’s ownness and becoming undone as a bounded being. Mikonytė’s Bust could precisely be understood as a record of the itinerary of such a creative disowning. Again, this should not be treated as an expression of a desire for a romanticist return to a Freudian oceanic feeling of infantile narcissism, or to a Piagetian primary narcissism characterised by a lack of strict boundaries between the self and the other. Rather, this disowning of one’s ownness, found in the creative process of Mikonytė’s work, should be understood as, on the one hand, an uncompromising embrace, on the part of the artist-existentialist, of finitude and of bodily vulnerability, and, on the other hand, as a search for new possible assemblages and reconfigurations of the parameters of one’s embodied being, on the part of the artist-cyborg.

There are two aspects of the exhibition that I believe support such, admittedly, speculative interpretation. First, the artist’s personal story of her battle with breast cancer, an experience with which this exhibition, in many ways, is a direct attempt to reckon. An attempt, that is, to welcome the ontological fact of sheer precarity of being an embodied subject, and to tarry with the pure negative (i.e. death) without shying away from it. Indeed, the video projection shown in the exhibition, titled The Negatives of Non-being – an ironic double negation which seems to describe a pictorial impossibility – could be taken as a statement apropos such an ontological fact. A video montage shows different versions of a sculpture-like prototype of a naked female bust submitted to various formal permutations, which becomes a vehicle, or a plaything, of mongrel cyber-organic forces threatening to claim the body to the non-human elements at any moment, to a point of no return. And yet, accompanied by overwhelmingly nostalgic sounds of synth-pop music, the angst that one might otherwise expect to be induced with is somehow warded off by an intentional and overt, saliently sweet sentimentality of Mur’s track. So, while the tarrying with the imminence of death, which Mikonytė painstakingly tries to convey, is thoroughly sincere and deeply personal, the viewer, on the other hand, is nonetheless, as it were, pre-emptively barred from wallowing in their own pensive and narcissistic moroseness to which a theme of death might otherwise risk inviting.

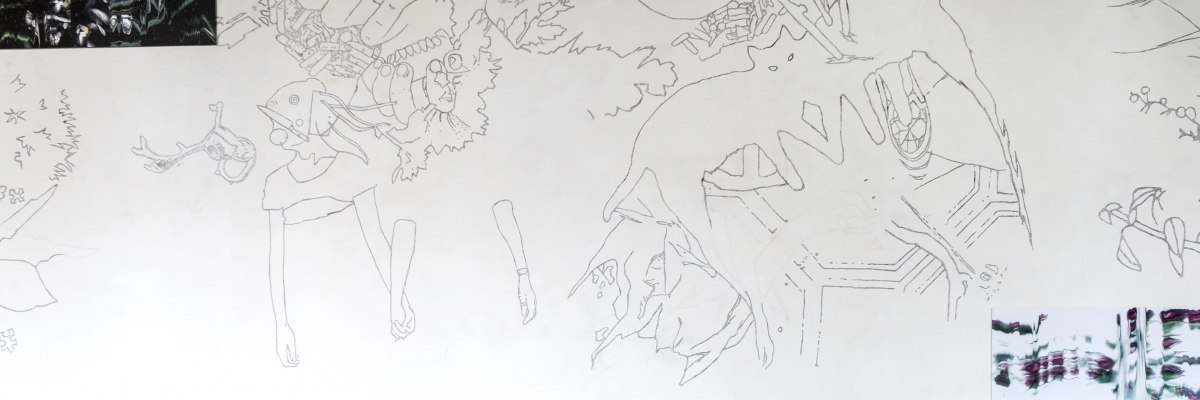

Then there are the wall drawings. These consist of the pencil reproductions of the tattoos that Mikonytė decided to cover her body with after a successful cancer treatment, not so much in order to mask the scars but rather in order to turn her skin into a surface that would register the interplay between the traces of the scalpel and the traces of the tattoo needle – an interplay of the imminence of death, convalescence and creativity. The surface of the gallery walls here becomes a literal extension of the artist’s body. Or, if you will, a new, non-organic skin stretched over the gallery walls. The meticulous process of re-drawing the tattoos from the surface of her skin to the surface of the wall could thus be seen as a tacit act of writing oneself under erasure.

What Bust intends to create is a space where the multitudes that one’s body contains are, if briefly, no longer one’s own. This is, without a doubt, what it means to attempt a creation of a genuine assemblage, whether with the elements of one’s surroundings (animate or inanimate) or with one’s fellow human beings. This latter point is worth underscoring. For, despite her own avowed admiration for cyber culture, the creative disavowal of her ownness should not be taken as a strictly anti-humanist statement. Rather, such an act seems to be first and foremost an attempt to give an expression to the common ontological fact binding us together (i.e. the precarity of flesh), and, perhaps, to simply celebrate it rather than inviting us to learn any particular lesson from it.

The exhibition is open until the 26th of June, Si:said gallery, Daržų st. 18, Klaipėda.

[1] https://www.lrt.lt/mediateka/irasas/2000108204/homo-cultus-is-balkono-paroda-kaip-pereinamas-pragaras?fbclid=IwAR1Q_m0KrFeri1ieu8hmLfLXbQ2dYD-n2BX4YfuHjsT2bsOSW5Jz7ayquC4

[2] Nietzsche, F. (2011). Dawn. Trans. Smith, B. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 105.

Photography: Si:said gallery