Post- Post- Soviet? Art, Politics & Society in Russia at the turn of the Decade. Ed. by Marta Dziewańska, Ekaterina Degot & Ilya Budraitskis, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 2013

Book review

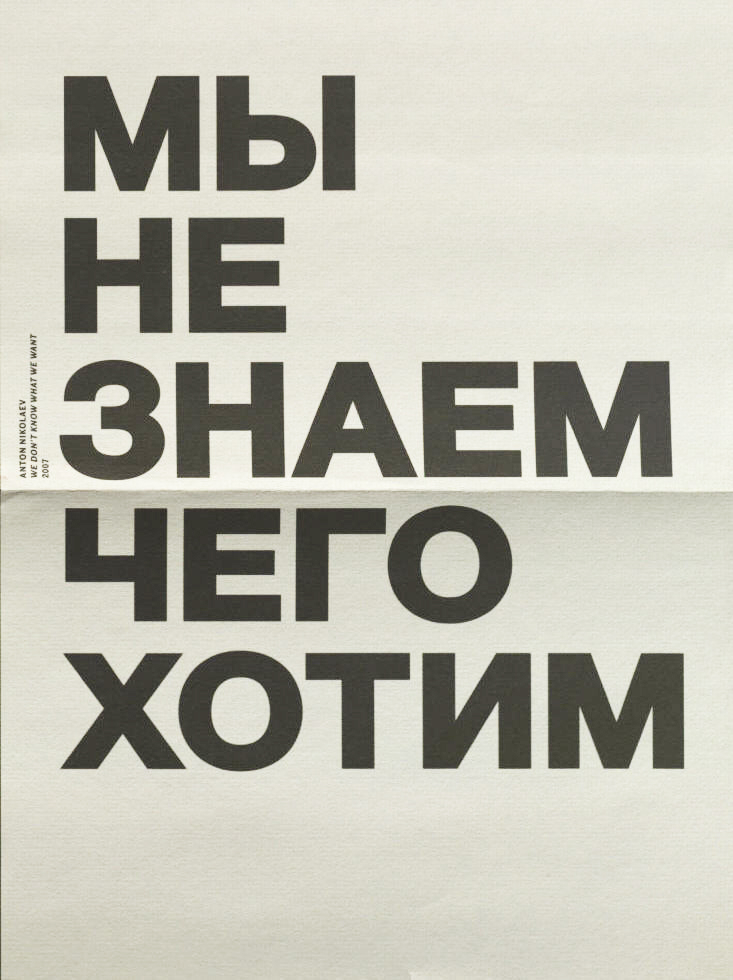

![Изображение[1]](http://www.echogonewrong.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Изображение1.jpg)

We are writing a new art history! Such is the slogan that opens a new book series by Warsaw Museum of Modern Art, dedicated mostly to contemporary (and Soviet) art from Eastern Europe. In a sense, that is genuinely progressive. Art scholarship in Lithuania, for example, often stagnates by chewing on the well-worn Western art history and debating who is the Lithuanian Van Gogh, Cartier Bresson or Koshut, while in many neighbouring countries they are, and have been for several years, actively writing and rewriting histories of various Soviet and today’s alternative art movements, thus contributing to a shared discourse on Eastern European art history and criticism.

This time, it is the seventh volume in Warsaw Museum of Modern Art’s series, dedicated to contemporary art in post-2000 Russia. Moreover, it focuses on politically-engaged practices. The book’s editors and co-curators of a show, Marta Dziewańska((Curator of the book series.)), Ekaterina Degot((Ekaterina Degot (born 1958) – renowned Russian art critic and curator. Author of several books on the Russian avant-garde and the Soviet informal conceptualism.)) and Ilja Budraitskis((Ilya Budraitskis (born 1981) – historian, art activist, co-editor of the Moscow Art Magazine, director of Moscow State Contemporary Art Centre médiathèque, member of the Russian socialist movement.)), are familiar names in Moscow’s art scene. The volume also serves as a catalogue for an exhibition that was held in Warsaw. The introductory chapter relates how the past decade has been seen as “stable” in Russia, yet disguised underneath this deceptive “stabilization” and “accumulation of wealth”, powered by Russia’s oil money, are hegemony of the oligarchs and relapses of Vladimir Putin’s authoritarian regime. In fact, many compare the last decade in Russia to Brezhnev’s period of stagnation.

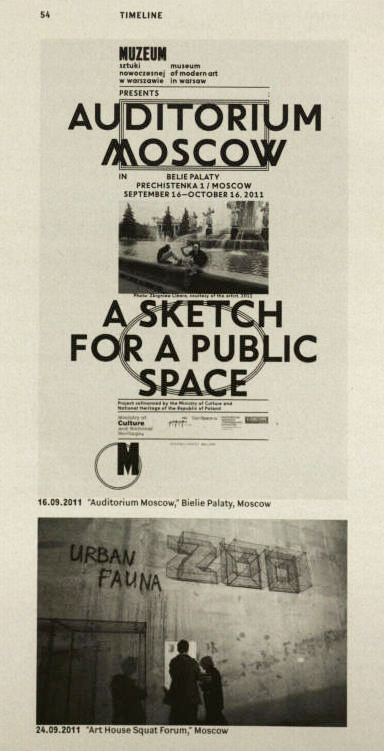

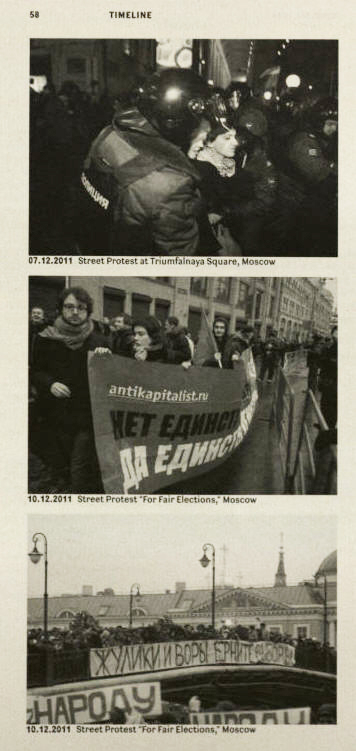

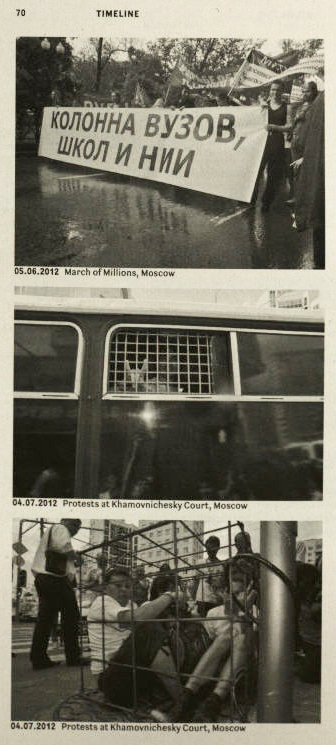

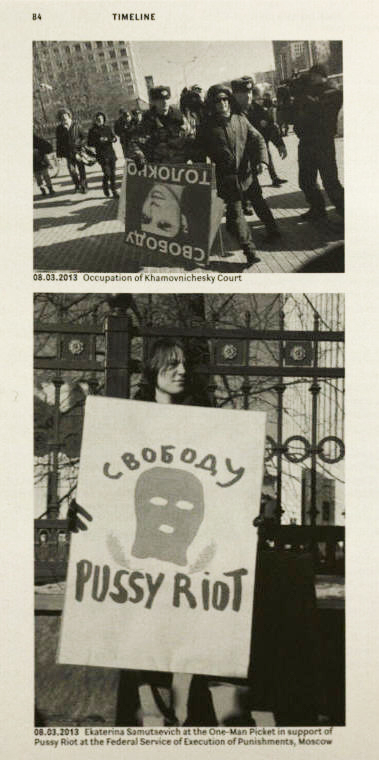

Further, part one of the catalogue contains a condensed overview of the most memorable sociopolitical and artistic events, intertwined together, since 2007, something that reaffirms the impression that Russia’s recent “calm” (including cultural) is but an illusion.

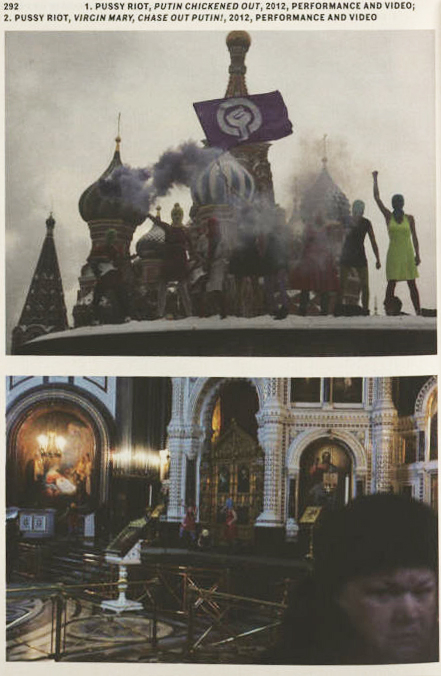

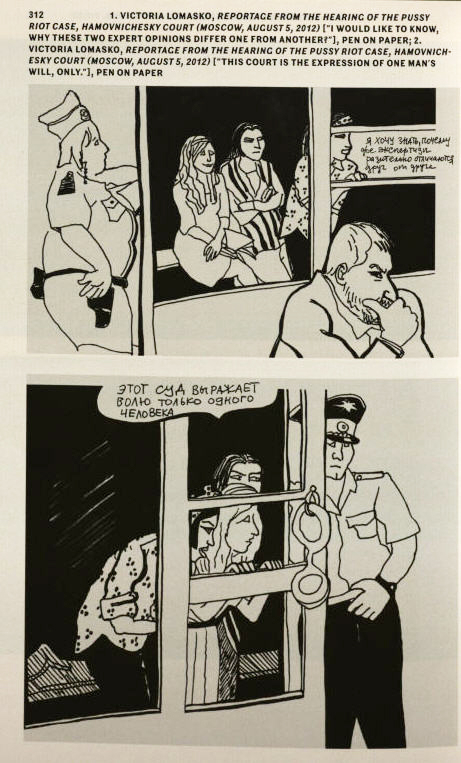

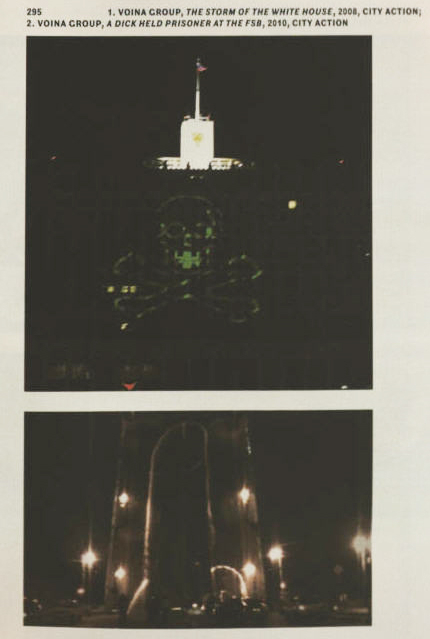

Russia is regularly shaken by deep sociopolitical and sociocultural contradictions that sometimes burst into bloody events. A case in point are massive rallies before the Duma elections in late 2011 that carried into protests against presidential election, i.e., Putin’s regime itself; or such radical countercultural phenomena like the punk band Pussy Riot or radical activist group Voina.

Part two of the book contains interviews with some of the most relevant Russian (as well as Polish, Ukrainian, Croatian) artists and scholars who engage with ideological contents or even direct protest practices, who study the interplay of sociopolitical and sociocultural contexts in Russia, post-Soviet and postcolonial mentalities; people like Artur Zhmijewski, Dmitriy Vilenskij, Dmitriy Gutov, Aleksey Penzin, Aleksandr Ivanov, Boris Kagarlitsky, Vladimir Malachov, Oleksiy Radinsky, Boris Buden, Ekaterin Degot, Arsenij Zhiliajev, Aleksey Tsvetkov, Marija Chechodanskich, Jegor Koshelev, Keti Chuchrov, Alek D. Epshtein, Vera Akulova, Ilya Budraitskis.

This section in the book presents an incisive and comprehensive sociophilosophical cross-section of Russia’s political, social and artistic life over the last decade. Granted, most of the rhetoric of the people chosen to represent critical theory and activist practices for the book is left-wing (occasionally even anarchist).

The reason why “left-wing politics” has such a bad name in Lithuania is – let’s be honest – is because of the genocide that the Soviet Union carried out here. Secondly, left-wing politics and theoretical (particularly academic) discourse still suffer from the weight of former Communist Party members (who have turned into oligarchs), retarded offspring of the former nomenclatura or the young theoreticians well-versed in euro-speak, all of whom completely fail to deal with the Soviet past, who indulge in pro-Stalinist rhetoric and hail Algirdas Brazauskas((Algirdas Brazauskas (1932-2010) – Soviet functionary, first secretary of the Central Committee of the Lithuanian Communist Party between 1988 and 1990. President of independent Lithuania (acting president 1992-1993, then elected for one term 1993-1998), later prime minister (2001-2006).)) as a “hands-on” Soviet-type lord. It is only natural that the “left discourse” carries very bad associations for many in Lithuania.

Therefore a qualification is in order here. The left-leaning artistic and critical-theoretical line that runs across this book is exclusively democratic and averse to any use of force and brutality. True, there are contradictions, certain discernible sympathies for revolutionary ideas. At the same time, however, most of the authors in this volume have long abandoned any Soviet revanchist prejudices and see the Soviet Union, at least starting with Josif Stalin’s reign up to the 1990, as a criminal bureaucratic regime (so is Putin’s) that has very little to do with the left-wing democratic ideology.

They equally acknowledge that the Baltic states were under occupation… On this point, there are no pro-Soviet reasonings. They also concede that the Soviet Union was, in a way, an ingenious system. It cannot be sentenced in a court, it cannot be subjected to lustration laws because almost everyone was involved. The intelligentsia and artists (at least in Lithuania) were very much a part of the system. Attempts to have a “genuine Nuremberg trial” for the Russian Communist Party failed almost instantly, after it emerged that the most enthusiastic proponents of the idea (including the “democraticallyelected” president of the country) had been members in the Communist Party and some even in the Politburo… So who should be sentenced?

Whereas in Lithuania, the ones who give a bad name for the left-wing discourse are people and organizations who are still nostalgic about the Soviet Union and therefore identify the left with a nakedly mobster-like regime. The book, permeated though it is with the left rhetoric, contains no traces of any proSoviet, revanchist innuendos. On the contrary – it attempts to trace, understand and articulate a place and a mission for politically-engaged art and leftist critical thought in the gap between the Soviet regime, that has discredited the left, and the new authoritarian regime.

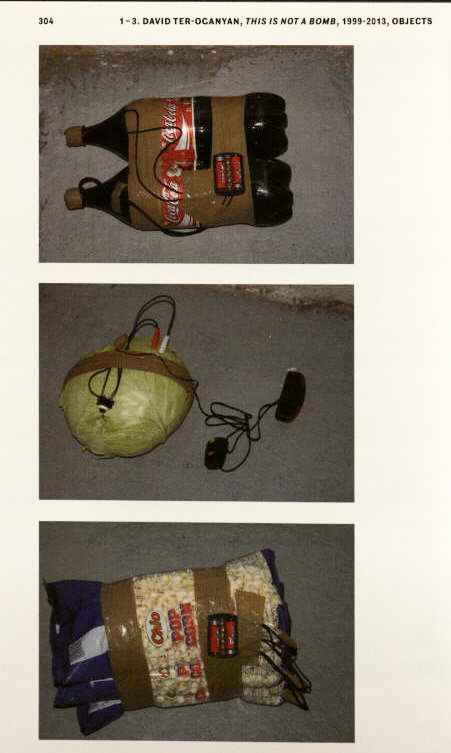

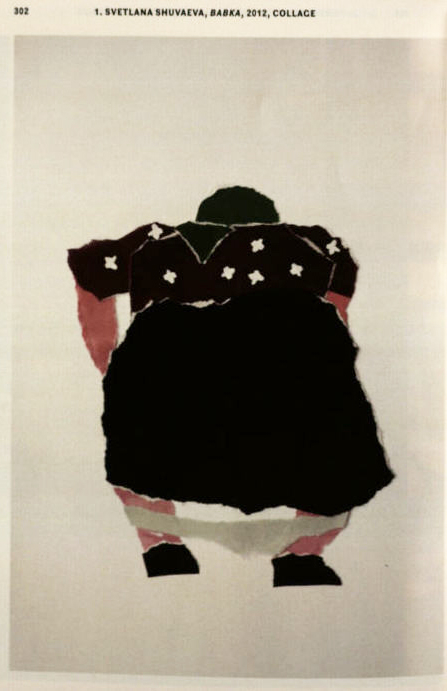

Part three of the volume presents the exhibition itself and contains reproductions of pieces by artists and activists who took part. Included in the show were artists who, over the last ten years, used their art to speak, either directly or in more aesthetic terms, about the politics of Russia, the (post-)Soviet condition or whose actions have transcended even the boundaries of “art activism” (like the imprisoned members of Pussy Riot or Voina).

Even though the book (as well as the show) has bypassed Lithuania, flipping through its pages makes one think about our own context – both because of the collisions over the “left discourse” and the suspiciously apolitical character of our contemporary art. Is it true that “politically-engaged” art is inevitably entangled in authoritarian regimes and is a sign of inadequacy? Or that countries like Lithuania – that (almost slavishly) aspire to copying and reproducing American and Western European art – have been walking the path towards maturity over the last two decades?

Political art is probably a deep-rooted tradition of Russian visual arts, one that dates back to Peredvizhniki and the twentieth-century avant-garde and has persisted via the informal Soviet conceptualism, the ideological actionism of the 1990s and the radical activism of the last decade.

In this respect, the Lithuanian tradition has never had so much open ideological engagement. However, if we look back at the wave of non-formal avantgarde of the late-1980s and the early-1990s, especially against the background of the Sąjūdis’ singing revolution, we could say it was a period of genuinely ideological avant-garde – indebted, in fact, to the left-anarchist Fluxus movement – even though the performative forms of the new art contained little open politics.

But what happened next (were we to construct a speculative “conspiracy theory”)? Two new – or allegedly reformed – institutions were set up: in 1992, Vilnius Contemporary Art Centre and, in 1993, Soros Centre for Contemporary Art; they began centralizing and simultaneously de-ideologizing the Lithuanian avant-garde, thus shaping the “new establishment” or, in other words, a new model for “official art”. Official art, as we know, is one characterized by loyalty, compliance and evasion of inconvenient ideological issues. After 2000, when the allegedly progressive above mentioned institutions won a decisive victory over “conservative” forces((After 1993, the Contemporary Art Centre was regularly subjected to attacks by the Lithuanian Artists Union and its conservative sympathizers. The last institutional clash started in 2005, but the CAC survived and prevailed.)), they ushered the so-called period of “normalization” or “stabilization” (have we not heard these terms before?).

All nice and pretty, if it were not for the fact that this de-ideologization and over-aesthetization of the Lithuanian avant-garde scene, re-branded now as “contemporary art”, is merely an attempt to gloss over inconvenient aspects of the post-Soviet (art) system. For example, the fact that in the early 1990s, in the midst of an institutional feud between the “conservatives” and the “progressives”, it was the “progressive” camp – i.e., those representing contemporary art – that underwent a simple dynastic succession; throughout its existence, the influential Soros Centre for Contemporary Art was run by offspring of influential Soviet nomenclatura families((“This field is dominated by a typical post-communist artistic development scheme: Latvians have their Helena Demakova, Czechs have Helena Kontova, Kazakhs have Valerya Ibrayeva, Poles have Anda Rottenberg, etc. (Lithuanians have Raminta Jurėnaitė and Lolita Jablonskienė – K. Š.) The entire region has been transformed into a cultural “filling” factory.” Redas Diržys, “Poetinė įžvalga: šaltasis karas tęsiasi”, in Kultūros barai, 2009, vol.12, p.12.)). The new generation of the Soviet nomenclatura dynasties has found this form of “avantgarde” exceptionally convenient – avant-garde purged of ideology and its critical potential, a “new fine art” which is preoccupied exclusively with “aesthetic issues”. German and English have replaced the Russian language, yet, upon joining the EU, the well-mastered Soviet-style bureaucratic lingo that went by the lofty title of “art study” was found to be no different from the Western equivalent.

The fact that the more politically-engaged (counter)artistic movements find themselves in relative periphery – like in Alytus (led by Redas Diržys) – while the capital city is dominated by the castrated pseudo-poetic mix of “neominimalism” and “neoconceptualism” – the “official” young art patronized by the Contemporary Art Centre and the National Gallery (we might just as well call it “neonomenclaturism”) – attests to the success of the (pro)Soviet forces in exploiting the revolutionary 1990s and the so-called (deideologized) “new art” in order to preserve, in slightly modernized forms, the same heavy, hierarchical Soviet-style institutional cultural system (as well as the bulk of their formerly-held privileges) where a few “godfathers” make all the decisions.

Everyone seems to have failed to notice how efficiently, under the veil of the Western-culture façade, we have been brought back to the (Euro-Soviet) Brezhnev era where we continue to live today. From that perspective, Post post soviet? can provide an important, albeit small, push for the thinking folk.