What do we know about the post-/socialist past? And is it really all we can know?((In order to represent both the differences and the correlations between socialism and post-socialism in one word I am using the term post-/socialist.)) Which previously unknown ways and prospects of responding to this time remain open, and which (alternative) insights are thus made possible?

Exhibitions, symposia and conferences dealing with the post-/socialist past since the 1990s have increasingly addressed the mechanisms that determine the historicisation of this era. It is open to debate how these processes of historicisation influence the perception of the time before and after the fall of the Iron Curtain.((For a detailed overview on exhibitions and curatorial practice in this context see Cătălin Gheorghe & Cristian Nae’s Exhibiting the “Former East”: Identity Politics and Curatorial Practices after 1989. A Critical Reader (Iasi/ Rumänien: Editura Artes, 2013) and Orišková, Mária, Curating ‘EASTERN EUROPE’ and Beyond. Art Histories through the Exhibition (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Verlag, 2014) )) One of the aims of these negotiations is described in the context of the Former West (2008-2016) event series: the idea is ‘to bring out previously overlooked or misunderstood fault lines that promise a different future or in any case lead us away from our habitual conception of matters.’((Maria Hlavajova, Former West – Dokumente, Konstellationen, Ausblicke, Einführung, 9. See also: http://www.hkw.de/en/programm/projekte/2013/former_west/start_former_west.php (as consulted 2015-02-18); the examination of a post-/socialist past is only one of the aspects discussed at Former West. Here, the role of the former West – and respectively its questioning – is the point of departure.)) Another essential aspect of the exhibition project The Forgotten Pioneer Movement (TFPM) is to look at the present and the future. In the program, flyer and the guidebook its curators talk about ‘approaching the past beyond mythologizing usurpation’, thus initiating alternative thought processes about these times. From there, societal perspectives for the future are to be investigated.((Ulrike Gerhardt, Susanne Husse: “Preface,” in The Forgotten Pioneer Movement – Guidebook (Hamburg: Textem Verlag 2014), 5-10.)) At this, the project focuses on works of art from the generation that spent its childhood and youth during the crumbling socialism and – mostly – post-socialism.(( See also: Alexei Yurchak: Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More (Princeton University Press 2006). Both Alexei Yurchak and TFPM focus on a specific generation: Yurchak investigates the social reality of the ‘last soviet generation’ – adults in the 1970s and 1980s. Researching historical documents such as personal letters and official speeches he develops a historiography of this generation. On this basis, he examines the (paradoxical) relation of this generation to socialism and its overthrow. In contrast, TFPM focuses on the following generation: children and teenagers in the 1980s and 1990s from formerly socialist-ruled countries. Both projects criticize a simplified perception of the era that is based on dichotomies and present a complex picture of ‘their’ generation’s political and cultural identity.))

The exhibition and performance project TFPM took place at District Berlin and in public places in the city. The interdisciplinary project (October 2, 2014 until November 29, 2014) was divided into three areas, so called sets: Set#A created the context for performances in the public space and workshops, Set#B was the actual exhibition at District Berlin and for Set#C artists and theorists gathered for the public seminar The Pioneer Camp of ReVision.((See Naomi Hennig’s description of the seminar: http://www.echogonewrong.com/review-from-lithuania/scattered-heritage-the-pioneer-camp-of-revision-seminar/ (as consulted 2015-02-18) )) References to the artistic and the curatorial research were presented in the Appendix Collection, an additional archival space that will move locations in the future.((The Appendix Collection is a research station containing related materials from the participants, the transitland: Video Art from Central and Eastern Europe 1989-2009 (curated by Edit András and Margarita Dorovska) and the TFPM-videos by Lina Albrikienė, bankleer, Vlad Basalici, Eglė Budvytytė & Bert Groenendaal, Irina Botea, Cooltūristės, Lenka Clayton, eteam, Christian Jankowski, Anna Jermolaewa, Szabolcs Kisspál, Jumana Manna & Sille Storihle, Wilhelm Klotzek, Jumana Manna & Sille Storihle, Anna Molska, VIP, Clemens von Wedemeyer, Katarina Zdjelar and others.)) The entire project was curated by Ulrike Gerhardt and Susanne Husse in collaboration with various discussion partners.((Ulrike Gerhardt and Susanne Husse have been working as a curatorial team since 2011. While Husse already examined the precarious, bio-political status of the body in her curatorial project dissident desire (together with Lorenzo Sandoval), Gerhardt investigates the interrelation of language and performativity in post-socialist contemporary art in the context of her PhD project at the Leuphana University in Lüneburg. The conversation partners were Agne Bagdžiunaite, Ana Bogdanović, Snejana Krasteva, Eglė Mikalajūnė, Maya Mikelsone, Anca Rujoiu and Ivana Hanacek, Ana Kutleša, Vesna Vuković of the curatorial collective [BLOK].))

TFPM was preceded by a two-year research phase during which the curators visited – among others – the Nida Art Colony, the curatorial collective [BLOK] in Zagreb, the Art Information Center at the National Gallery of Art in Vilnius, the Latvian Center for Contemporary Art (LCCA), the Feminist Critique of the Contract summer camp in Žeimiai, exhibition spaces such as tranzit or Salonul de Projecte in Bukarest and many more places in East and Central Europe. In order to provide a frame for the transitional generation, the curators adduce the figure of the pioneer. According to them, the pioneer figure is a shared empirical tableau of this generation and thus suitable to ‘examine the manifold marks of educational institutions and publicly mobilized ideologies in both the former ‘East’ and ‘West.’’((See also the exhibition programme at www.district-berlin.com))

Although there are fundamental differences between the socialist and the capitalist neoliberal system it is nonetheless worthwhile to dismantle this general opposition and look for similarities and parallels.((In her article „Radical Archives“ Sarah E. James deals with exhibition projects, who attempted a more nuanced remapping of the socialist imaginary. Sarah E. James „Radical Archives“, Frieze Magazine, Issue 17, February 2015 – http://frieze-magazin.de/archiv/features/bilder-fuer-eine-andere-zukunft/?lang=en (as consulted 2015-02-25) )) For this reason, the exhibition displays works that contain a questioning of the learned dichotomy between East and West and the related hierarchies.

This review is intended to provide an overview over the subjects and positions of some of the works in the exhibition/ Set#B. My main question is: Which examinations of the post-/ socialist past influence the artistic practice of this generation, and how are they reflected?((Ana Bogdanović describes this generation in her essay Generation as a framework for historizing the socialist experience in Contemporary Art which is included in the guidebook: ‘The age group in question here corresponds to that of the ‘last pionieers’ whose formative critical period occurred at the time of late socialism and early post-socialist transformation. Its specifity, compared to previous generations, is therefore the distant and mediated memory of socialism, comprehended as experience at the very moment it was becoming historical.’ Ana Bogdanović, “Generation as a Framework for Historicizing the Socialist Experience in Contemporary Art,” in The Forgotten Pioneer Movement –Guidebook, 33.))

The exhibited works can roughly be divided into two approaches: Firstly, artworks that contain the past rather subtly and, secondly, politically motivated works that relate to specific events and biographies in history and present age.

The collective ŽemAt from Lithuania, the Office for Anti-Propaganda (led by Marina Naprushkina), the performance group bankleer and Marta Popivoda of the public seminar program are part of this second, artistic-political approach. Using various methods they work on the post-/ socialist past and ask how these reflections change the perception of the present (neoliberal) social situation. Among the pursuits that look at the past on the basis of local styles, schools and vogues are the works of Mitya Churikov and CORO Collective. Through their observations they develop an unfamiliar representation of the interwovenness of the cultural spheres ‘East’ and ‘West’, which were formerly perceived as separated. I want to briefly mention four artistic positions that allow for a very personal perspective on the post-/socialist past: In her videos and photographs Lina Albrikienė relates subjective memory to collective memory; Claudia Rößger works on memory through the graphic examination of myths and hybrid beings; Ēriks Apaļais approaches memory processes via the pictorial-semantic interpretation of signs; in his portrait photography Nicu Ilfoveanu relates to the life of a friend in a Romanian village.

Despite this attempted classification, the discussed works are based on very different experiences and observations, not least due to the heterogeneous forms of post-/ socialisms in different countries.((Ieva Astahovska mentions this in her essay Socialist Past between History, Imginary Memories and Cabinet of Curiosities, which is included in the guidebook: ‘The post-socialist period itself is often characterized in terms of a hopeless identity or a struggle with the leftovers of the past. While it is hardly possible to avoid using the concept of post-socialism, it is worthwhile to attempt to zoom in closer and explore its rather hybrid and complex nature. In reality, there were different socialisms and there are different post-socialisms, as each socialist society has faced distinctive conditions and each decade has experienced a markedly divergent dynamic.’ Ieva Astahovska, “Socialist Past between History, Imaginary Memories and Cabinet of Curiosities,“ in The Forgotten Pioneer Movement –Guidebook, 15.)) The exhibition project and the selection of works avoid the widely criticized process of canonisation and categorization, thus finding a way to admit and display this heterogeneity. What remains confusing is the classification of the artists exhibited as members of a pioneer movement, even though the latter is labelled as fictional by the curators. The approaches and motivations of the artworks are too diverse to suggest a common political or artistic aim of this so-called ‘forgotten pioneer movement.’ Below, I will introduce two positions each from the suggested approaches in order to clarify the spectrum of exhibition Set#B.

The artists’ collective ŽemAt works at various levels against normative notions, renegotiating the significances of private ownership and community, of periphery and center, of individualization and collectivity. Countless documentary photographs, statistics, texts and diagrams concerning the current economic and education policy situation in Lithuania represent ŽemAt’s examinations within the exhibition’s architectual modules.((The exhibition display was designed by the KLOZIN–Büro für Präsentationslösungen under the direction of Wilhelm Klotzek and David Polzin.)) On the neighboring wall the video Imagining the Absence (2014) is shown. Here, the display appears specifically in the aesthetics of an amateurish commercial message with a clear purpose, reminiscent of information boards used in teaching institutions and schools. The guidebook explains: ŽemAt is short for Žeimiai Technical School of Aesthetic Thought and Anonymity and was founded in 2006 by Agnė Bagdžiūnaitė and Domas Noreika.((Members: Eglė Ambrasaitė, Agnė Bagdžiūnaitė, Noah Brehmer, Eglė Mikalajūnė, Domaš Noreika, Aušra Vismantaitė.)) The collective lives in a manor-house in the rural town of Žeimiai where it organizes artistic and cultural events as well as the Residencyoyo.((For further information, see: http://residencyoyo.zeimiudvaras.lt)) The aim of their program is the prompting of ideas of a community in a place characterized by agriculture. The video Imagining the Absence shows a group of students of teaching and psychology as well as members of ŽemAt discussing the Lithuanian reform movement Sąjūdis which was active at the same time as the perestroika and then forgotten. During the improvised talks questions concerning the lack of influence of Sąjūdis on the political and societal present of Lithiuania are raised and theatrically imagined in short episodes.

A central question about these blank spaces and absences for both the ŽemAt collective as well as for the context of TFPM has been raised elsewhere by Agnė Bagdžiūnaitė: ‘I sometimes wonder if we in the Eastern Bloc perceive the current system as a regime that is suppressing us and leaving us speechless, as if nothing changed and the transition did not happen. All that has happened is the replacement of one form of denial with another: one denial is dedicated to the past and the other to the present.’((Agnė Bagdžiūnaitė, Sydney Hart, “Revising a Strategically Demonized Past,” Fuse Magazine, no. 35-4 (Fall 2012), 30.))

Marta Popivoda’s contribution to the public seminar revealed the connections between past, present and future. Her film How Ideology Moved Our Collective Body (2013) contains insightful observations on former Yugoslavia’s socialist past. For two years the filmmaker researched in film archives in Belgrade and Paris in order to relate public TV and political propaganda images to one another. Looking at her country’s history, Marta Popivoda investigated how social choreographies like mass events and demonstrations have changed over time until after the war in the 1990s. Amongst other things, these mass, collective and self-performances indicate the executors’ self-image and their relation to their country. In addition to the well-researched archival image material, the film’s strongest point is the voice-over in which Marta Popivoda reveals her thoughts about the images and asks why ideas of equality and community were exchanged against inequality and isolation.

By contrast, the video Vocabulary Lesson (2009) by CORO Collective presents different connections: the artists of the collective((The members are Eglė Budvytytė, Goda Budvytytė and Ieva Misevičiūtė.)) process questions of (self) representation and identity by combining styles of architecture, fashion and dance.((An excerpt can be found at https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/asset-viewer/vocabulary-lesson/LgF3ZOgsNY3n3g?hl=en (as consulted 2015-02-18) )) Against the backdrop of the Vilnius Palace of Concerts and Sports’ constructivist architecture which illustrates the promising future of a collective community at the time, you see members of CORO Collective voguing. Voguing is a dance form practised by the African-American, Latino, gay and transgender community as an act of emancipation and was introduced in Harlem, New York City, in the 1980s. It is derived from models’ poses in the fashion photographs of Vogue magazine. Apart from this emancipatory Ballroom Culture CORO Collective also addresses modernist currents and the voice-over includes quotes by Gertrude Stein and Frank Zappa. In their video they condense various cultural appropriations that took place multidirectionally and globally.

From the engagement with architecture and the different evaluations it has experienced over time, Mitya Churikov derives primarily sculptural questions. At TFPM he shows the installation Untitled (Kajima Corporation 1978): A grey carpet with an edged outline is spread out on the floor. Glass fragments are positioned in the middle and on the edges; angular abstract floor elements are placed around the installation. Videos are projected onto two panes of glass, showing a rural landscape and a city landscape. The installation refers to the Internationales Handelszentrum (IHZ) on Friedrichstraße, Berlin, which the former GDR government commissioned the Japanese building company Kajima Corporation to build. Using the architectural elements glass and concrete, Churikov installs object landscapes that display formal borrowings from modern architecture. Through the deconstruction of the architectural elements he also deprives them of the ideology they were once built and viewed on, hereby integrating them into a new process. At this, similarities to ever-changing urban landscapes become evident. The work is based on observations of the new Soviet architecture that was developed as a counterdraft to traditional construction and the associated form of government. In a sense, the changes and ideologies of post-socialism formed this building anew. Untitled (Kajima Corporation 1978) can be understood as an attempt to interrupt this cycle and to present the elements simply as what they are: glass and concrete.

The exhibition in Berlin provides an important contribution to the discussion on the historicisation process of a post-/socialist past, mainly by looking at the generation shaped by upheaval. The works show how the young artists provide an important impetus for a new interpretation of present and future. This is possible due to the critical examination of cultural, social and political phenomena under the influence of post-/socialist experiences.

Also read: Scattered Heritage: The Pioneer Camp of ReVision Seminar (Set#C) by Naomi Hennig, 28 10 2014

Claudia Rößger, Constellations (2012), series of drawings, exhibition view, The Forgotten Pioneer Movement, District Berlin 2014 © Emma Haugh

CORO Collective, Vocabulary Lesson (2009), video, installation view, The Forgotten Pioneer Movement, District Berlin 2014 © Emma Haugh

ŽemAt & Aikas Žado Museum Live, Imagining the Absence, installation view, The Forgotten Pioneer Movement, District Berlin 2014 © Emma Haugh

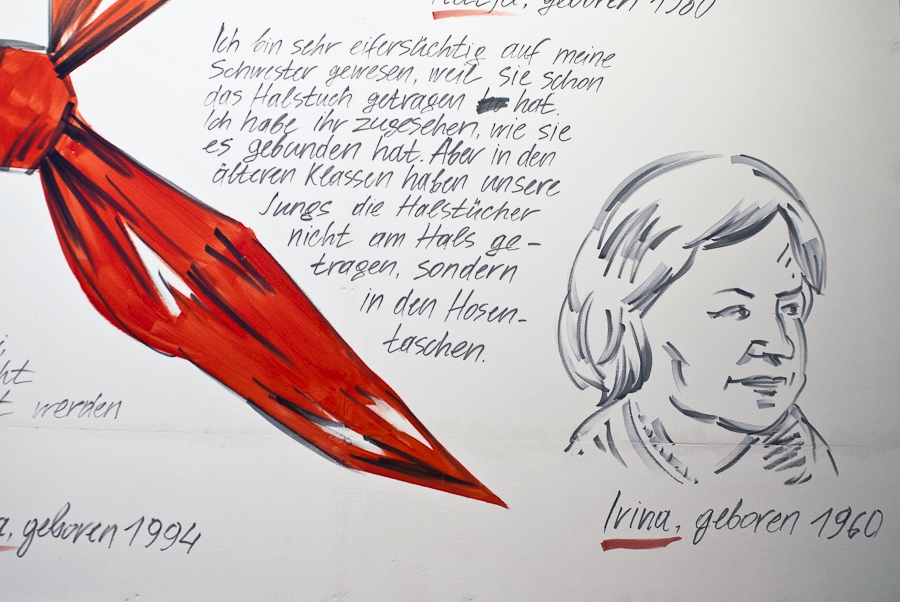

Marina Naprushkina, Politics and School, walldrawing, installation view (detail), The Forgotten Pioneer Movement, District Berlin 2014 © Emma Haugh

Marina Naprushkina, Encyclopaedia for Ideology-Workers and Politics and School, video and walldrawing, installation view, The Forgotten Pioneer Movement, District Berlin 2014 © Emma Haugh

Mitya Churikov, Untitled (Kajima Corporation 1978), sculpture, installation view, The Forgotten Pioneer Movement, District Berlin 2014 © Mitya Churikov

Mitya Churikov, Untitled (Kajima Corporation 1978), sculpture, installation view, The Forgotten Pioneer Movement, District Berlin 2014 © Mitya Churikov

Marta Popivoda, How Ideology Moved Our Collective Body (2013), film screening, The Forgotten Pioneer Movement, District Berlin 2014 © Emma Haugh

ŽemAt & Eglė Ambrasaitė, Imagining the Absence, video, installation view, The Forgotten Pioneer Movement, District Berlin 2014 © Emma Haugh

ŽemAt & Aikas Žado Museum Live, Imagining the Absence, installation view (detail), The Forgotten Pioneer Movement, District Berlin 2014 © Emma Haugh

ŽemAt & Aikas Žado Museum Live, Imagining the Absence, installation view (detail), The Forgotten Pioneer Movement, District Berlin 2014 © Emma Haugh

Mitya Churikov, Untitled (Kajima Corporation 1978), sculpture, installation view, Universität der Künste Berlin 2014 © Mitya Churikov