Once upon a time, a childless couple decided to make a child from snow. The snow-child came alive, and shortly afterwards turned into a young girl. They treated her like their own daughter, and she became part of the village. One day, the other village children invited her to go out into the woods to pick berries. Seeing that while they were idle the snow-child had picked a lot of berries, they became jealous of her and killed her. They buried her and planted willow branches on the grave. Back home, they told everyone that the snow-child went missing in the woods. A merchant and his child happened to go past the little grave. The boy took one of the branches and asked his father to carve a flute from it. Every time the flute was played, the snow-child’s tragic story was told, how her two friends had killed her. One of these friends was given the flute, but she refused to play it. The flute broke, and out of it emerged the snow-child again (‘Das Schneekind’, from: Volksmärchen, ed. by Erna Pomeranceva, 1964, pp. 48-50.)

This fairy tale was recorded in 1948 in southwest Siberia by T.N. Lyashko, and is just one of numerous versions. To some, the story might sound familiar, and yet every version is unique and striking. The snow-child, or snegurochka in Russian, has been a source of inspiration for many writers, composers and artists, including Mikhail Vrubel (1856-1910), who painted the snow-child as his wife, the singer Nadezhda Zabela, who sang the leading role in Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera Snegurochka (1881). The particular tale quoted above is not just about a child made of snow and a flute that reveals a crime, but also about art, and we may discover that it could also be about Eriks Apalais’ art. In discussing Apalais’ first large overview exhibition ‘Family’, I will try to illuminate some key aspects of his work, such as the visual and literary language, words and images, storytelling and visual retellings. How does his work address the desire for the word and the image? How should we understand the visual and literary figures in his paintings, and what kind of painting is it?

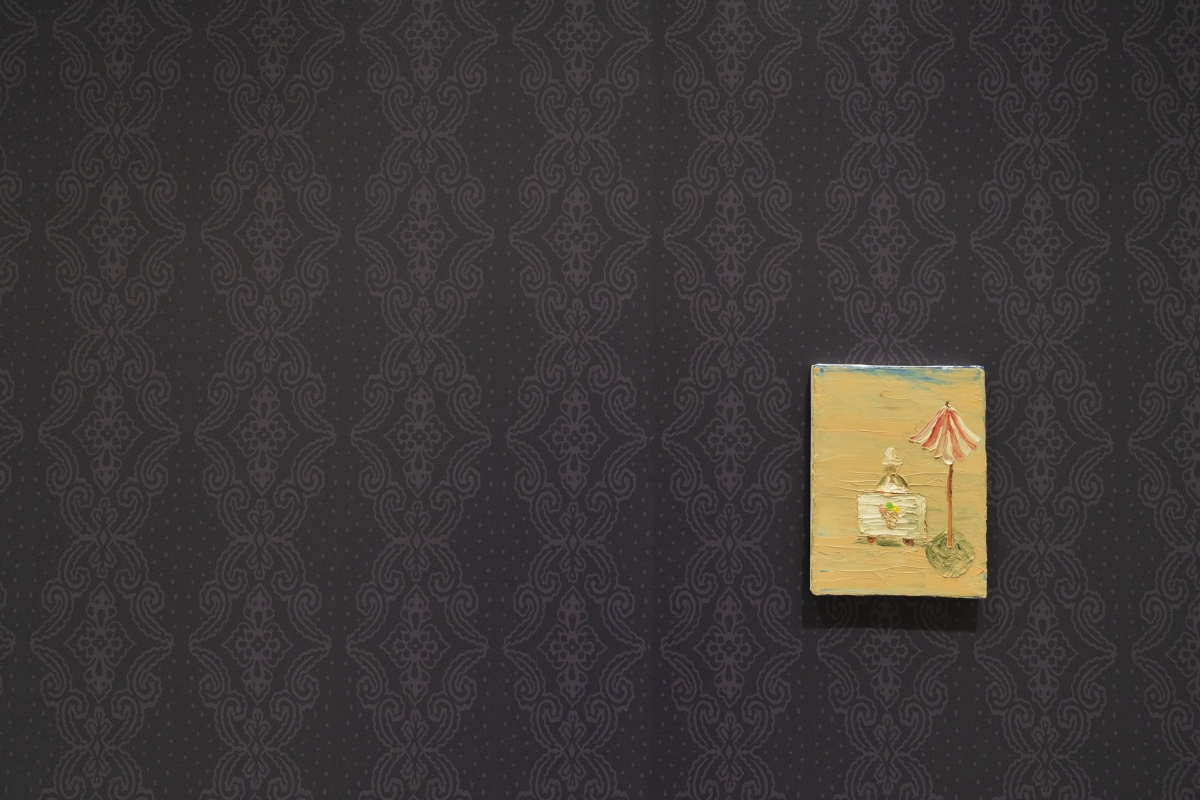

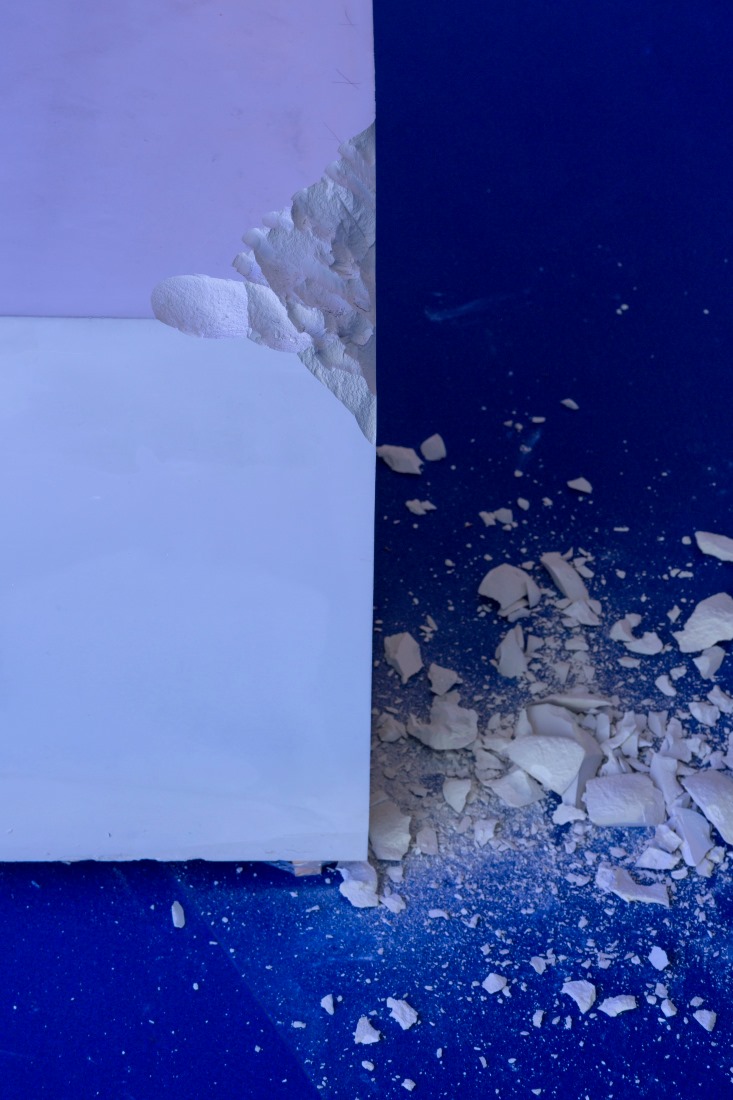

Fairy tales, as Apalais himself explains, were part of his childhood. It can be argued that not just the characters and objects of fairy tales made their way into his art (snowmen, mushrooms, geese, woods, Jack Frost, strawberries, snow, etc), but also the intimate atmosphere of being read or told a fairy tale. His paintings resonate with various powerful and memorable experiences, such as contemplating the night sky, the first snow, seasonal celebrations, summer in the countryside, watching films, and reading books. All these experiences can be associated with intimacy, namely with being together with a special person, or the absence of that person. This intimacy appears to be fundamental to his art. It is reflected by the design and organisation of the exhibition. The long corridors with paintings on dark wallpapered walls produce a homely atmosphere, and might remind the viewer of the experience of looking at pictures in someone’s home. This antithesis to the white cube presentation of art is maintained throughout the exhibition by means of low lighting and dark interior design. Certainly, the dark space is also a cinematic space, which also resonates with Apalais’ interest in cinema and film. But in a more general sense, the opacity of the walls has a homely side to it. It makes the paintings appear ‘private’, like part of someone’s life or personal story, emphasising Apalais’ engagement with autobiography as a genre. The paintings exhibited in this way draw the viewer into their interior space, as opposed to being presented more objectively on white walls as commodities.

The exhibition is organised chronologically. It begins with Apalais’ first paintings, from 2006 to 2008, the beginning of his time at art school in Hamburg. There are strawberries, animals and beautiful birch trees in vivid colours. Then, from 2011 to 2017, we have paintings of figures and letters in white or black on grey backgrounds. The objects depicted here do not seem to be from childhood imagery any more: typewriters and textbooks are more ‘grown up’, and even the snowman is now ‘serious’, that is, not a happy, friendly snowman any more, but a combination of highly controlled brush strokes (Fig. Snowman 2007). With the latest ‘Tukums-Tomsk Series’, which addresses the Soviet mass deportations to Siberia, of which Apalais’ grandmother was a victim, the artist returns to his attempts to deal with the relation between memory and narrative in his early paintings. This return is a success, insofar as it facilitates a deeper reinterpretation of these early paintings. With the ‘Tukums-Tomsk Series’, we know that the experience that underlies it is the deportation and all the loss, lack and suffering that goes with it. Here, Apalais acts as a listener to his grandmother’s stories, and subsequently as the illustrator:

„Mom was reading fairy tales in childhood and when my grandmother was telling stories about Siberia it was a similar feeling. As a child I would fantasize and interpret the words with images.“[1]

Snowman,50×50, oil on canvas, 2007, Courtesy Latvian National Museum of Arts. Photo: Toms Harjo

Storytellers often use vivid images. Fairy tales have simple, often predictable, narratives, recurring motifs and types.[2] Sometimes the only feature that sets one fairy tale apart from another is a certain image. That image can be a motif of the narrative which sticks in the memory of the listener, or it can derive from a certain interpretation by the listener. In this case, it only exists in the listener’s head, or if it is an artist, in his or her work of art or illustration. Apalais illustrates his patchy memories of his grandmother’s stories. This patchiness of remembering an experience is precisely what is fundamental to his early and subsequent paintings. The trees, twigs and teddy bears in his work are not the main characters in a happy tale, but certain images that have stuck (Fig. Tukums-Tomsk (Green Armchair, 2019).

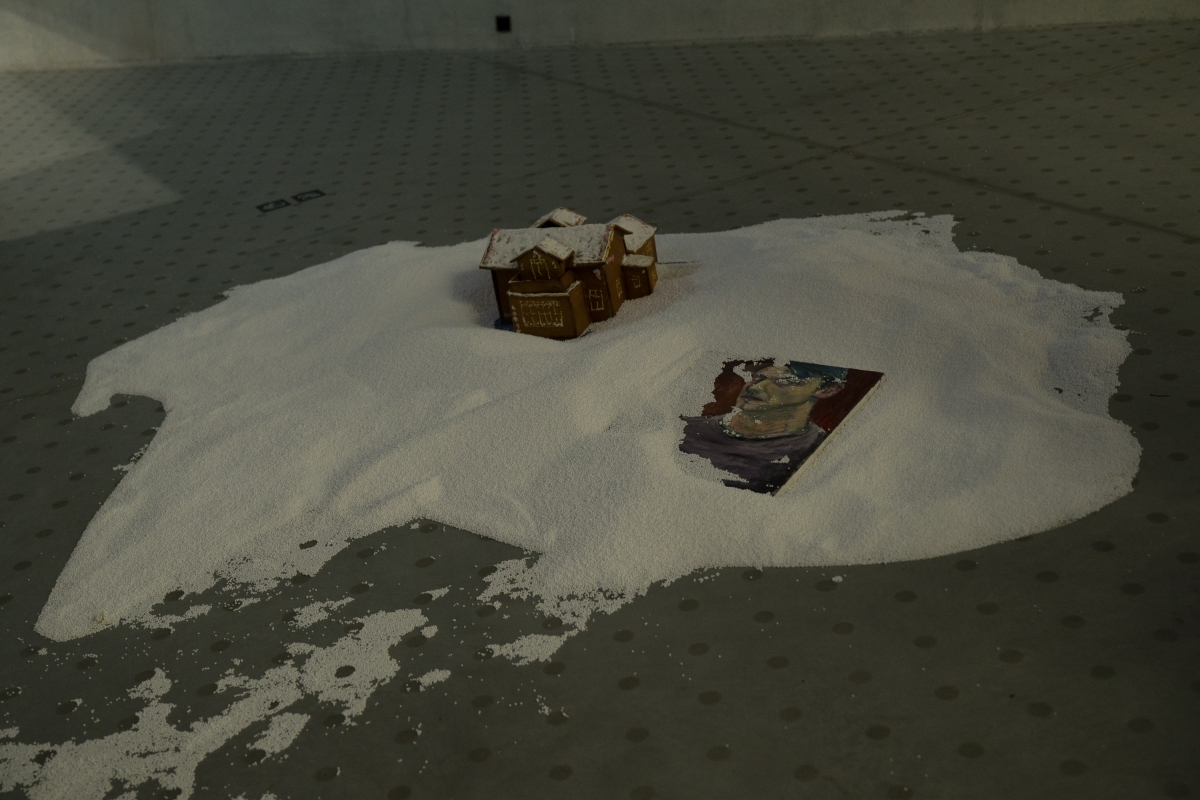

One of the most emotional exhibits is the installation Home (2020). A large projection shows a sad young boy looking downwards (a film still from Bergman’s film Fanny and Alexander, 1982). On the left-hand side, there is a tall Christmas tree, and on the floor, we discover a gingerbread house covered with artificial snow. The gingerbread house is a famous motif from Grimms’ fairy tale ‘Hansel and Gretel’. This particular tale is a specific type: about children who get lost in the woods, or are abandoned there by their parents for various reasons. After being abandoned, the children wander aimlessly through the forest, and several hungry days later, they miraculously come across a gingerbread house. Contrary to what some people think, the tale pre-dates the relatively recent tradition of baking gingerbread houses for Christmas. The gingerbread house has become a symbol of the fulfilment of children’s desire to eat as many sweets as possible, ideally ‘a whole house’. It makes sense that after several days of starvation, children develop a craving for sugar. But the house has a more ambivalent and darker significance. It can be interpreted as seeking redress for being abandoned. In an even darker sense, the gingerbread house can be understood as a hallucination shortly before death. The artist has made this gingerbread house a miniature replica of his grandmother’s house, where he used to spend the summer holidays as a child. The use of snow indicates his attempts to translate his own experiences (personal childhood and summer) into a broader cultural context (fairy tale and winter). The placing of the house on the floor has deep implications. For an adult, it remains barely visible on the floor: devalued by its placing beneath the line of vision, it appears slightly pointless. For children, who spend most of their time playing on the floor, the gingerbread house has a magical effect. The viewer is invited to imagine herself or himself as a child again, and to rediscover that forgotten perspective. In the snow, we find a self-portrait of the artist. Looking away from the viewer, he is studying himself sceptically in an invisible mirror.

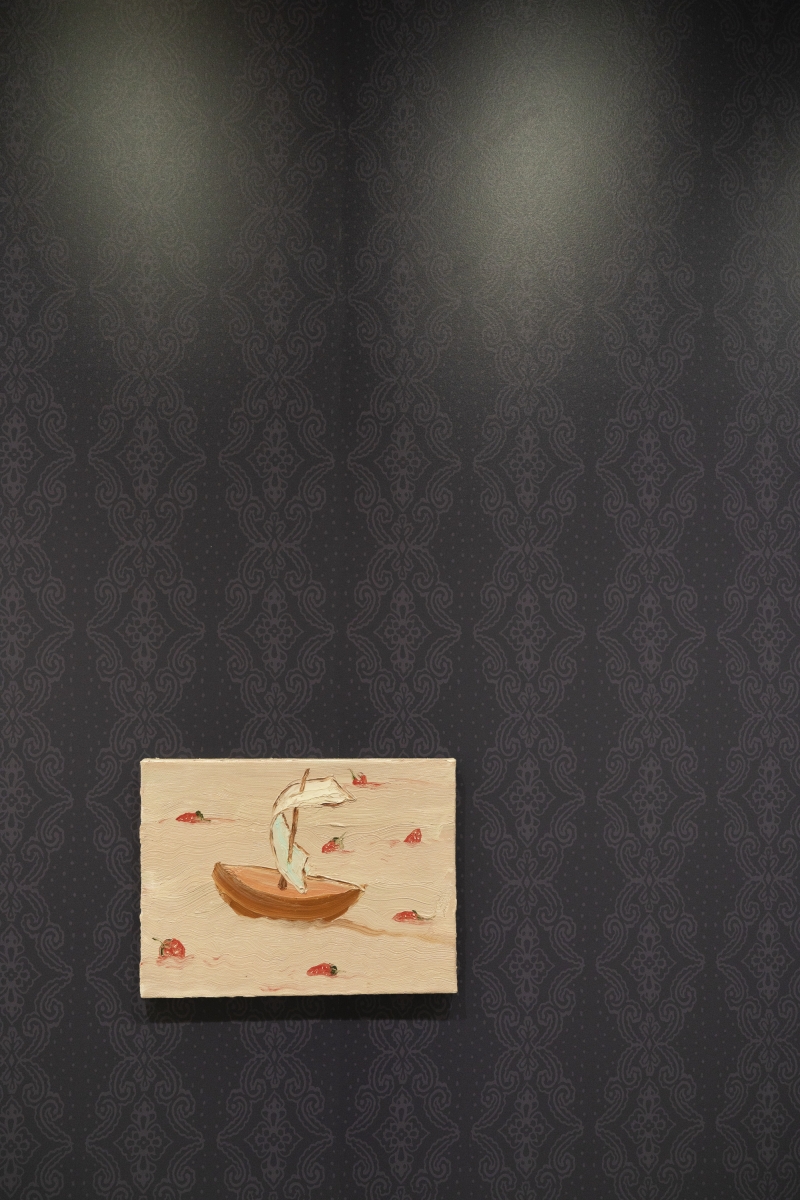

From the gingerbread house, we can follow up the food theme, which resonates with powerful cravings and enjoyment. A little boat in a creamy sea with strawberries; an ice-cream stall in a seaside resort. The socialist childhood is often associated with lack and shortages, but at least there was always ice-cream and home-grown strawberries in the summer at the dacha! (Figs. Strawberry sailboat, 2007/ Pumpuri, 2007).

Enjoyment is sometimes associated with naivety, innocence and childhood. Apalais’ early paintings capture the untainted, pure enjoyment of nature, spring, the joy of observing animals, the fresh colours of the first leaves. But in his paintings enjoyment is not oblivious. Some instances of uncanniness express a fundamental drive to overcome contrary emotions. Children can also be confronted with powerful emotions, which overwhelm them at times with need, frustration, lack or loss. Some argue that children need fairy tales in order to deal with emotional stress.[3] As in Ingmar Bergman’s film, which Apalais quotes in his exhibition, the young boy struggles with the difficulties that life and his family impose on him. He tries to escape into a world of fantasy and imagination. This flight is sad and fascinating at the same time.

His paintings are indices of condensed and intense emotions. In Christmas and Easter at Once (2007), we discover the expression of conflict of enjoyment. The Christmas tree with candles and a friendly bunny rabbit are set against a black background. This could be interpreted as the family tensions that emerge at holidays, when everyone gathers together, surrounded by festive decorations. The decoration cries out to be heard and seen in the dark mood. And this is true of most of his early paintings: they have something fundamentally sad, but also fundamentally joyful, about them. In these paintings, the signs of conflicting experience are not even original. But the objects and characters of fairy tales, and even the tales themselves, are mostly not original. Fairy tales are captivating not because of their content, which is often very predictable, but because of the way in which they are read or told. This is either the intimate story-telling situation, or the literary form of retelling fairy tales. In both instances, it is about the tone, sound, manner, performance and gesture, and not about the novelty of what is being said.

Apalais likes to paint the same motif over and over again. Perhaps he hopes that this will shift the initial, painful meaning of the motifs? It is not boring, just as it is not boring to listen to the same tale over and over again. In some respects, this is true of all high culture, such as film, which can be watched many times. Each time, we come away with a different reading.

In one of Apalais’ numerous pieces of writing on his artistic practice, he analyses theories of early language acquisition.[4] He writes that words, as opposed to abstract concepts, that are bound in an obvious way to certain objects, are easier for children to learn, such as ‘clouds’, ‘the sun’, ‘the house’, ‘the animal’. As his paintings are inhabited by such objects, at first, they may seem to lack any conceptual level. But this is deceptive, since we know that the figures are indices of conflicting experiences, and that the practice of painting them over and over again is an attempt to shift the initial meaning they had for the artist.

Another key aspect of Apalais’ artistic practice is the painterly technique. Painting is understood by him as a kind of language. Just like language, images and visual objects can be broken down to elementary forms. Once this process has taken place, parallels with language emerge naturally. Just as a word can have two meanings (homophones), one brush stroke can constitute several meanings: a book or a seagull (V V, 2014). In Le cygne (2015), an additional specific brush stroke transforms ‘the book’ or ‘a seagull’ into a swan. Le cygne and le signe are French homophones, they sound similar but mean different things: the swan and the sign. In W lily (2014), the process of deconstruction is especially clear: torn away from the flower, the single petals float in a dark space and reveal themselves as a combination of fine brush strokes. The fragility of the flower and its deconstruction by the painterly gesture is very touching. The outlines of two petals have been separated as well, now they appear as a reversed ‘W’ or an ‘M’.

It is interesting to note that children learn words very easily if we combine the pronunciation with a gesture. This makes sense especially when more conceptual words are at stake. For example, when saying ‘goodbye’, you wave. And perhaps something equivalent can be found in Apalais’ painting: the brush stroke means an object, but it is also a gesture, thereby intensifying the production of a conceptual meaning.

Let us turn to the snow-child once more in order to make one last point. This is the most difficult point, since a snowman is the catchiest symbol in Apalais’ work.[5] At the right temperature, making sculptures out of snow is an effective and easy way to create shapes, which goes back to ancient cultural practices. In Apalais’ paintings, these basic round shapes are turned into celestial bodies, which is also significantly intensified by the exhibition design. Here they appear as little moons in the dark night sky. We can detect the attempt to deconstruct the personal and cultural meaning that is heavily loaded on to the snowman (or the snow-child). The large painting with a white snowman against a black background in Words (2010) in particular attempts this. The head of the snowman is ‘just’ a circle, the torso is not a torso any more, but ‘just’ a moon, and the bottom is ‘just’ a cuddly ball of fur. The bits and pieces that are floating in the painting, such as a broken stick or an ‘8’, register the process of deconstruction and its potential to produce new meaning. These transformation processes are heavily controlled through the use of certain brush strokes. In Vrubel’s painting, we also get curious painterly gestures, which appear to shift the meaning by means of different brush strokes. The seam of the snow child’s coat is painted by using the same brush strokes as for the snow. In one case, it represents bits of white fur, and in another layers of snow. The snow appears further in another form, namely as a symbol of the snowflake, and then as part of her coat, and as her earrings, and her hair clips. In Vrubel’s painting, we also get a shift of meaning: the cold snow turns magically into warm fur. This may be considered a wish image akin to the gingerbread house, insofar as the threatening, even deathly, qualities of snow are transformed into an image of comfort. In Apalais’ painting, conceptually something similar is happening as in fairy tales and their illustrations, but it is taken further towards abstraction (https://www.wikiart.org/en/mikhail-vrubel/the-snow-maiden).

If we suspend the moral interpretation of ‘The Snow Child’ tale, then we can discover an artistic meaning behind it. In the first place, the snow-child is a product of wishful thinking. But the fairy tale sends us on a journey with this unreal ‘child’. ‘Real people’ get involved in it, crossed by it. They ‘kill’ it, and then bring it back to life again, but this time from a stick. By playing the flute, the snow-child re-appears as a musical sound. The story is told to us once again in a different form. The flute gets destroyed, but this makes the snow-child come alive again. The snow-child is unbreakable, because she is unreal, and this makes her even more real than anything else. Perhaps a similar point can be made about Apalais’ work: his paintings make his desires come alive, and by trying to dismantle them and the narratives that haunt and inspire him, he makes them even stronger. Deconstruction is key, but his fundamental desire for images is unbreakable. This is what makes his art so fascinating, absorbing and charming.

Exhibition view. Photo: Toms Harjo

Untitled, 2018, oil and acrylic on canvas, 195 x 135. Photo: Toms Harjo

Tukums-Tomsk (Green Armchair), 2019, 225 x 350 oil and acrylic on canvas. Photo: Toms Harjo

Pumpuri, 2007. oil on canvas,18 x 14. Photo: toms Harjo

Strawberry sailboat, 2007, oil on canvas, 25 x 35. Toms Harjo

Christmas and Easter in One, 2007, oil on canvas 30×24. Photo: Toms Harjo

Home, 2020. Photo: Toms Harjo

Exhibition view. Photo: Toms Harjo

Le Cygne, video projection

Exhibition view. Photo: Toms Harjo

Exhibition view. Photo: Toms Harjo

Family portrait, 2019, oil and acrylic on canvas, 225 x 175canvas. Photo: Toms Harjo

Exhibition view. Photo: Toms Harjo

[1] Eriks Apalais, ‘Role of Cognitive Strategies Studying Visual Art’, unpublished manuscript, 2020, p. 40.

[2] Cf. Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale, 1958; Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk Literature, 1932-36; 1955-1958; Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index [1961] 2004.

[3] Cf. Bruno Bettelheim, The Uses of Enchantment, 1976.

[4] Cf. Eriks Apalais, ‘Role of Cognitive Strategies Studying Visual Art’, unpublished manuscript, 2020.

[5] Tales about making a child also exist in Latvia, Russia (Kolobok), the USA and England (The Gingerbread Man), and other north European countries. AaTh 2025: ‘The fleeing pancake’: a woman makes a pancake which runs away, various animals try in vain to stop it, and finally a fox eats it up; AaTh 703: ‘Artificial child’: an aged, childless couple raise a crayfish instead of a child, carve themselves a child from wood, make one from snow, and the like’ (found in Lithuania, Russia, Serbia). The Types of the Folktale. A Classification and Bibliography. Antti Aarne’s Vezeichnis der Märchentypen (FF Communications No 3), trans. and enlarged by Stith Thompson, Helsinki 1961.