Zane Onckule: Hi, how are you?

Viktor Timofeev: All right, but stressed out! I’m finishing this collaboration that’s due to open in a few days. It’s with jodi.org, as part of their show in Amsterdam, and of course there are still a lot of technical problems and last-minute changes. I’m more than excited though, because they really inspired my whole world ages ago, so it’s incredible to be doing something together. There have been so many levels of mediation going back and forth over the last few months.

ZO: What will be in the show?

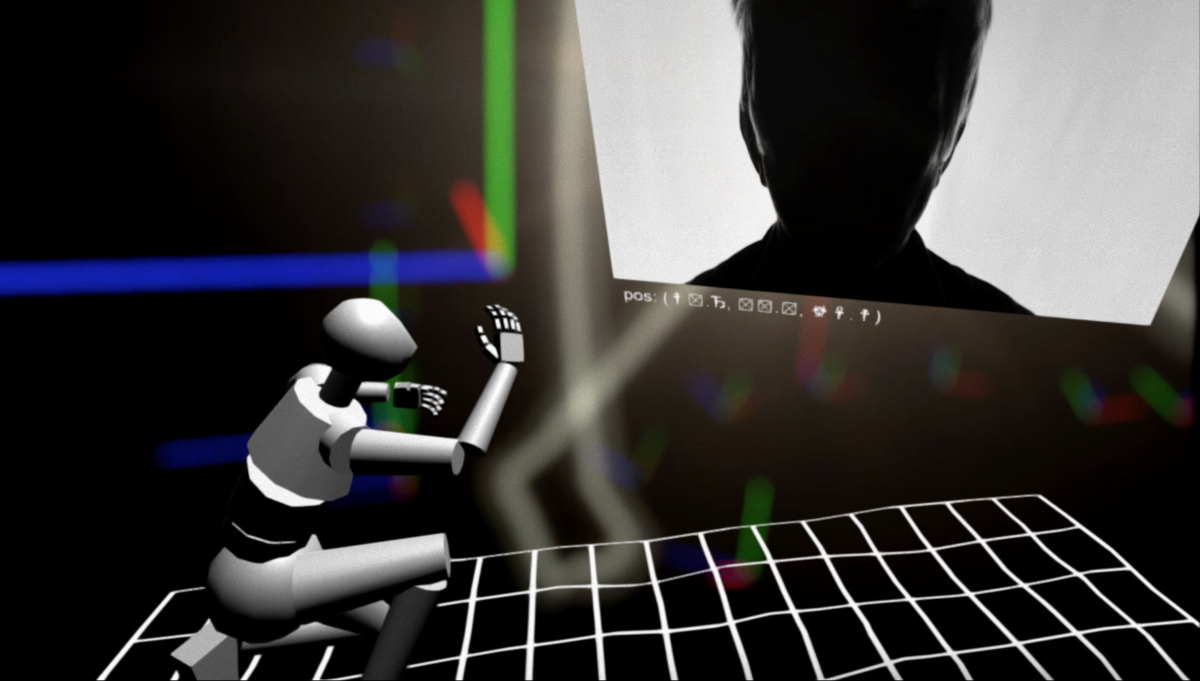

VT: It’s their work, plus this collaboration, which is a virtual reality piece made of several ‘interfaces’ initially conceptualised for the Oculus GO, a new stand-alone headset (no cables). It comes with a swivel chair that kind of induces motion sickness as much as possible. The work takes a sceptical view of this new tech, while being engrossed by its possibilities. It’s a bit of a bottleneck for my brain, as I haven’t been able to do anything else, like adjust to the physical reality of living in a new place.

‘GO20’, collaboration with Jodi.org, VR software (still), 2018, courtesy of Upstream Gallery, Amsterdam.

ZO: The good news is that it’ll soon be over, and you’ll be able to start working on your relationship with the city and the people here. Can you tell us a bit about coming back to NYC? What are your hopes and expectations about what you’d like to do and experience here?

VT: I’m very confused in terms of where I feel at home, which I guess is normal when you move around. I lived here for twelve years, since I moved here with my parents in 1997 until moving away in 2009 to do my MFA in Europe, which took me nine years, because I kept dropping out of programmes until I found the right one. So now I’ve come back, and I’m finding it strange to be displaced at this age, not really having roots in one place. It’s hard establishing new relationships in your thirties (at least it has been for me), but I hope to meet new people and renew old friendships. But, basically, I was feeling pretty emotional about being closer to my family, so I acted on that impulse.

ZO: Is there anything particular about the city itself? Does it fit your practice better than others?

VT: I guess I like the insanity of it, but I just wanted to be here, both as a new environment and as a place where I have some history. After graduating from Piet Zwart in Rotterdam, I stayed an extra year to reassess the next ‘move’, do some exhibitions, and have some time to breathe. But while doing so, I grew more and more lost, and slipped into a depression, for one reason or another, not realising it until I was in it. I made some great friends, and really enjoyed my time; but overall, I just had to go. I think I missed the chaos of a big city. I was also chatting regularly with my brother, trying to explain how to do basic skateboarding tricks. I filmed myself doing them to send him, and then it struck me that we’ve had this abstracted relationship for years now. I wanted to have some meaningful interaction, and make a mark on him while he’s still growing up.

ZO: Skating, huh?

VT: Well, yes. I’ve been skating for twenty years. When we moved here, skateboarding helped get around the social dynamics at school. I was bullied a bit because of my accent and background, and skating gave me an identity based on this subculture, separate from nationality. Then I seriously thought I might get some sustainable sponsor, before I realised that I’m not going to have the career that I envisioned after all. This feeling creeps into my art practice now as well. But the realisation was, or is, liberating, because you switch into a different mode, and start seeing shades of grey within the system … and things become fun again, at least with skateboarding. It’s also a way of dealing with longevity or the constantly receding horizon. Anyway, I was trying to help my brother remotely, but it’s quite hard trying to teach skating while being geographically removed, writing about foot positions, body weight placement, and so on. It’s all muscle memory. So, for the whole of this year, he was trying to learn how to kickflip, and I tried to support and inspire him through text messages and my own videos. Now, in two weeks of being here and skating together, he’s already landed it, which is a big deal. It’s the realisation that it actually is possible: the abstraction becomes real. I don’t know if my being here contributed, but I really was happy to witness it.

Studio at Piet Zwart Institute, Rotterdam.

Stills from video messages with my brother.

ZO: The phrase you used, ‘muscle memory’, has an interesting connection with your practice, in which one project continues and develops into another. Would you agree that this embedded, learned and experienced knowledge is then further stretched and applied in your art?

VT: With every new show I have, I challenge myself to try out something I haven’t done before. So I try not to get too comfortable with muscle memory in that definition, but I think it’s good at least to know where this personal strength lies, and to harness it selectively. This has been changing recently, as I’ve been working on some projects that I felt I haven’t fully maximised in one go; so, for the first time I’ve been reiterating on some of them, making new versions or sequels.

ZO: Speaking of new versions and sequels, can you take us on a tour of your practice, a sort of leap describing your subsequent steps (or not) that further turns into works?

VT: Somehow, it was intertwined with skateboarding from the start … I was doing my BA at Hunter College, studying computer science, but actually all I wanted to do was to skate. I had a pretty bad injury, which made a dormant auto-immune condition flare up, without a probable recovery. I got into art as a tool for therapy, as something to ‘fall into’ and structure a schedule around, something that facilitated my escape into a secondary, internal world. After dropping out of computer science, I got into art history, and then into making art. I found that art helped my mind, and eventually my body. Max Beckmann and El Lissitzky were my early favourites. Fast forward a bit, and I started making, exhibiting, selling paintings and drawings. I was skating again. Then there was another flare-up of my condition, which triggered another kind of paradigm shift. I got into ephemeral, distributable materials, including websites, music and performances. It’s hard to explain, but there was something that overlapped between the disruption I felt to the systems I was applying in my drawings and paintings, like basic perspective, and the corporeal defeat I felt from this chronic pain, which pushed me as far away from rules as possible. But it was only a matter of time before I came back around to it, although I think from a different angle: in my first websites, rules became labyrinths, and linear paths became randomized. In this way, the systems I previously used reached their natural extreme end point. Then I discovered game engines, and that became the totality of it all: world building, behaviour, choreography, sound, and so on. But that’s not to say I’ve stopped drawing or painting; in fact, I’ve been doing more of it than ever, maybe as a result of another recent flare-up of my condition.

‘3 AM’, watercolor, ink on paper, 2005.

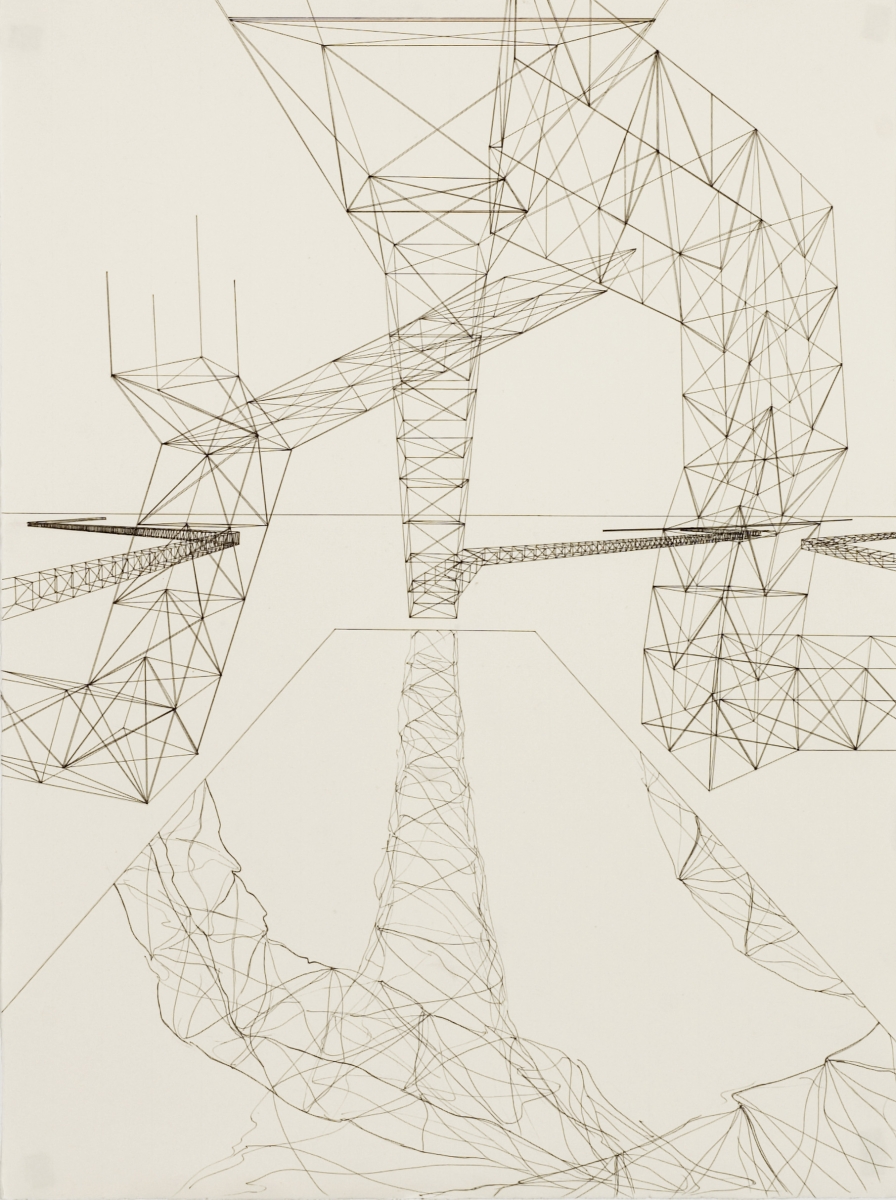

‘Looking’, ink on paper, 2008.

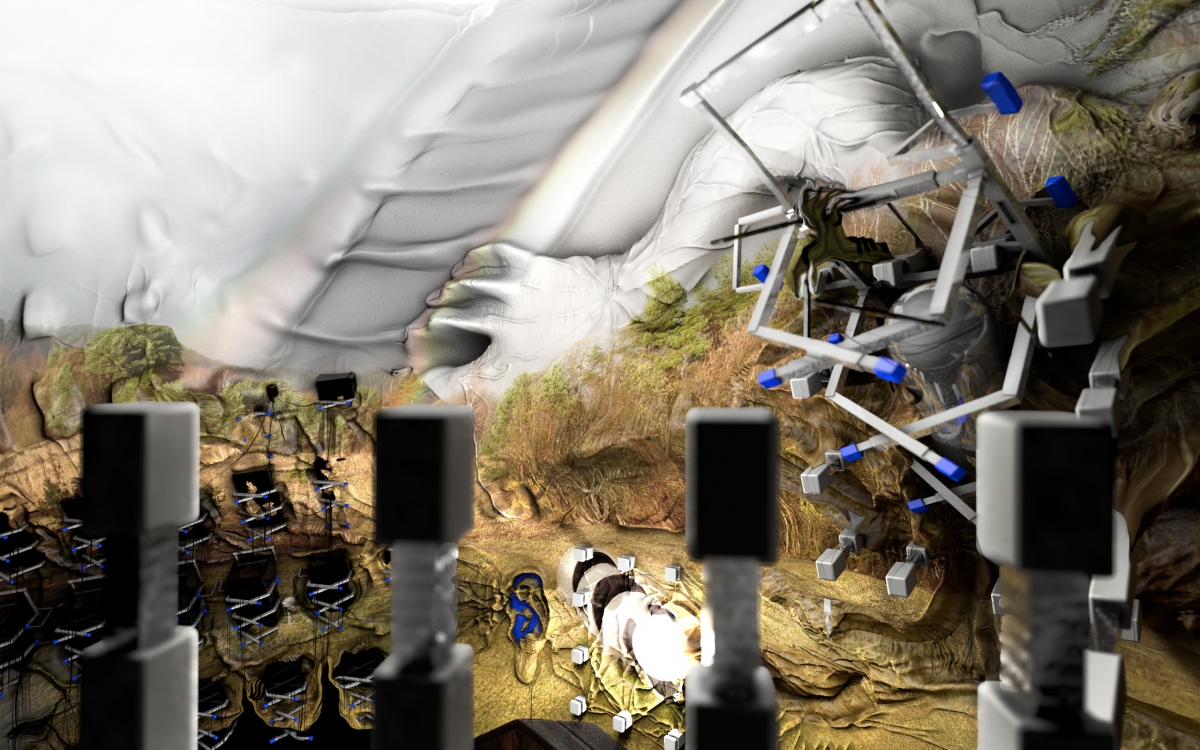

’Soft War 1’, computer-generated image, 2014, courtesy of desktopresidency.com

ZO: What’s it like then, this world you’re building?

VT: It’s something both personal (internal) and something that seeks a relatable platform modeled on consensus reality (external); It’s kind of autobiographical, but also autonomous and free of function: A parallel, exaggerated sandbox version of the one I engage with on a daily basis.

ZO: Do you return and revisit (some of) them as you move forward with each new project?

VT: Yes, all the time. While working on one thing, I really like revisiting older ones, to remember how or why they came to look and work the way they did. Each one is ultimately a marker of that time in my life, reflecting my state of being and thinking, crammed and cubed up into a project, which makes it hard for me to reuse a project without conjuring up all the emotional baggage it comes with. But maybe that’s actually a healthy thing to do for future projects: pure, uncut baggage, the more the better!

ZO: To talk more about more, let’s speculate on where it would eventually come from. What inspires or interests you today?

VT: I’m currently a hundred per cent tuned in to Erik Davis, whose podcast Expanding Mind I greatly recommend. I just finished an older book of his, Techgnosis, which covers shifting forms of belief in technology across the centuries. His podcast touches on everything, from theology to artificial intelligence and psychedelia. He talks a lot about the unknown universal force that some call God(s), others pure Chaos, and the rich blurriness in-between. Otherwise, I’m also currently reading a book on the choreography of Trisha Brown. It’s really hard to pinpoint external sources of ideas, for they often don’t necessarily make absolute “sense”. Maybe it’s my way of trying to enforce left turns in my interests.

ZO: You’ve done quite a few collaborations with artists, musicians, and others across different media. I wonder to what extent your individual practice is influenced or guided by them? Generally, how do you usually create?

VT: I find that collaborations are a great way to take a left turn, and generate some new thinking. Especially for me, as I have a tendency to overcomplicate everything when I’m left alone. I have a few projects during which I was left alone in a room for a year, coming out of the ‘cave’ with them having made leaps from A to B to C to D … all the way to Z. And then showing somebody the Z, while telling them about A, and they usually had no idea what was going on, or how I got to Z. I started to think it’s really good to take a left turn to go in a direction that you wouldn’t normally allow yourself to go in. I think it’s healthy to be forced to lose control.

‘Inscrutable Lick’, collaborative drawing with Anni Puolakka, coloured pencil on paper, 2018, courtesy of Cordova, Barcelona.

‘4.5/5.5’, collage, 2015, courtesy of Futura, Prague.

ZO: So collaboration helps you visually and conceptually to unease it all?

VT: It helps me to lose control, which I sometimes have problems with. It’s a huge contradiction, because I try to control how I lose control. I make lists about possible ways to lose control. But I try to find ways of sabotaging that side of myself as well, deleting project files to prevent future versions, throwing dice (that doesn’t work so well).

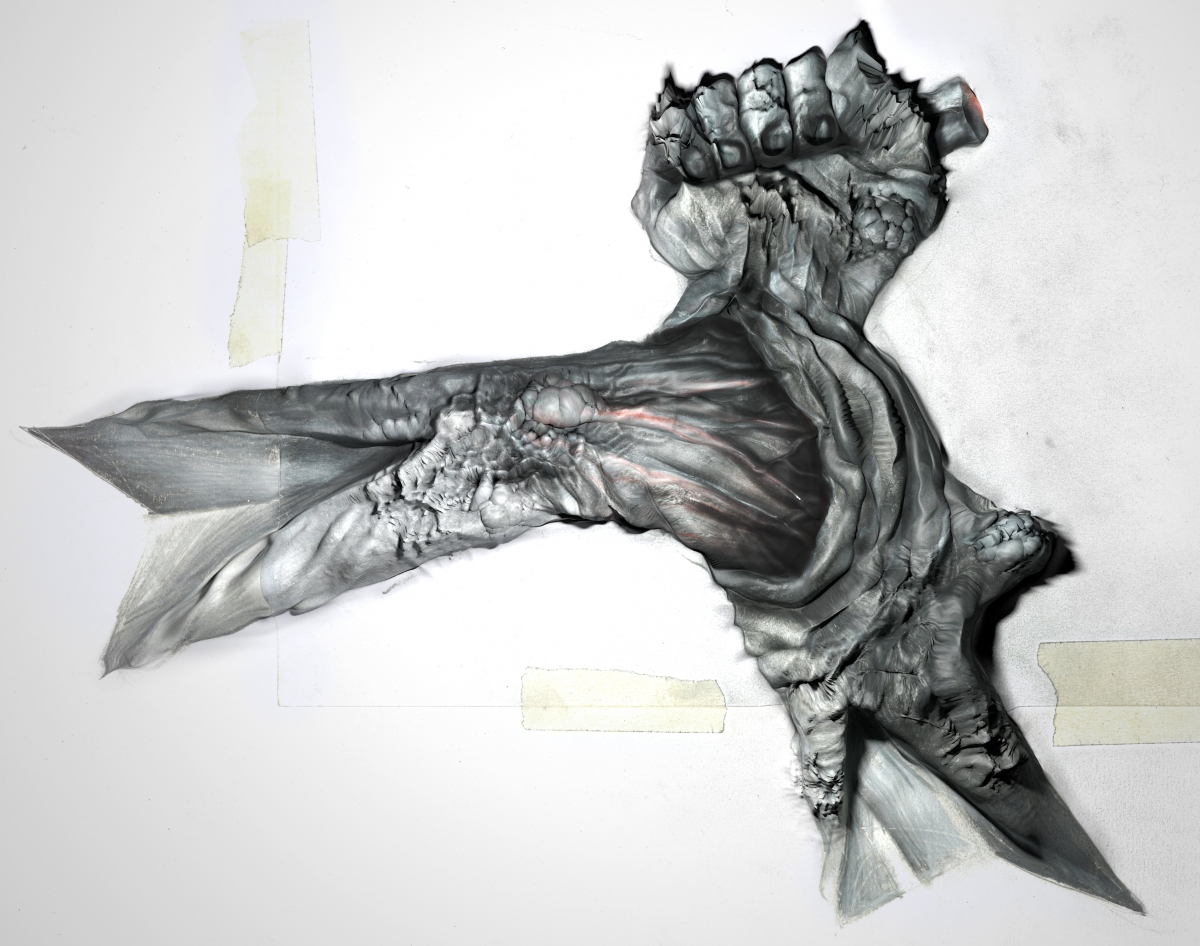

ZO: Looking back at your existing body of work across all media, what stands out is an abundance of insects, like cockroaches, a greyish tonality, and a recurring presence of hands in various sizes and shapes. They all seem to make up your vocabulary.

VT: A couple of years ago, I found a folder of drawings that I made when I was eighteen. They were from around the time I was dropping out of computer science and getting into art, going through the chronic pain thing. Emo Egon Schiele-style drawings. At the time, I was still making works with rules, and I felt something got lost in those ten years between my ‘early’ hands and the ‘rule work’. I thought I had to take some of this back. I felt I could reappreciate the subject matter, to see those teenage hands anew … and so I started to reincorporate hands and other corporealities into my work. I think hands are generally amazing, as they have an eternal base subject matter, because it’s probably the part of your body you see most of, every day. You never come to terms with them, but you also learn not to see them.

ZO: Also, cockroaches. What do they signify? Are they an error, a ‘worm’ in the system you’re putting up?

VT: With the cockroaches and bugs, I was thinking about simple rules created to fit a reductionist view of complex behaviour. I bought these Hexbug toy bugs that are made for kids: they vibrate, move, and turn right when they hit a barrier. I started to play with them for fun, and found myself getting lost in their behaviour when more than two were introduced into the same space. I started to programme this behaviour in my digital bugs, to see how I could imitate this in a game engine. Absurdly enough, I found myself believing in their ‘emergent’ behaviour, even though I had clearly just written the basic code for it. And what’s more, I felt I could embody them, as if I were this creature (it could have been my state at the time).

ZO: A Kafka-esque bug-type of entity?

VT: Yeah, certainly identifying with these simple choices: stop, go, turn left or right. I can’t deny that a level of complexity arose out of those base rules, and I wanted to harness it. Also, cockroaches use randomness to avoid danger, and I find that kind of instrumentalised unknowability very interesting, and something I want to learn! But I’m also scared of roaches, which is why I made the digital bugs into cockroaches in the first place: to observe how I would feel about them in simulations. I found that my game helped me to deal with this problem, and I had a pretty tame response when I found one in a room I was staying in. To give you another example, in ‘Proxyah’, the game I showed at kim? in Riga in 2014, the player’s avatar is constantly being forced into a body of water, while being attacked by all these visual stimulations. I actually have a fear of being under water, from when my Latvian swimming instructor held my head under the water at the Natālijas Draudziņas Ģimnāzija in Riga. Because of that, I almost have a panic attack when under water: even when it’s a game! Developing ‘Proxyah’ numbed me to it in the same way. I hope there are some fundamental ‘relatabilities’ in these experiences, which is why I’m driven to share them.

ZO: Your deep sound listening nights, or ‘listeances’ as you call them, seem to fit into this logic of sharing. What motives and thoughts are behind these transformative events?

VT: I started these events in Rotterdam in my pitch-black attic. Basically, a monthly gathering, a space for internal imagery to be generated with the aid of loud music. There are ritualistic properties to it, such as the consumption of special food sometimes complementing the material we listen to. Light is completely eradicated in the attic, making a space that’s free of visual stimulation and distraction. You lie down with your eyes open, and just listen to records or pieces from start to finish, while completely awake and attentive. There’s no talking. I did it in Rotterdam for two years, and I’m now starting it in New York; we did one last week at 15 Orient in Brooklyn, and I’m already planning the next one. It’s extremely simple, and tries to make room for something rare: darkness. I also find it gives me the chance to think clearly for two hours at a stretch. I wanted to share this possibility with my friends.

‘Physical Capacity’, VR software, 2017, courtesy of Two Queens, Leicester.

Photos from ‘IDYLLLIMBOR Listeance #15 co-hosted with TARWUK’.

Photos from ‘IDYLLLIMBOR Listeance #15 co-hosted with TARWUK’.

ZO: Coming back to the gaming environment, can you tell us about your decision to write/program failure into your games? I’m talking here about the frustration of trying to win in ‘Proxyah’, the game you made for the solo show at kim? in 2014. Humans have a strong desire to succeed at whatever they do. But they certainly can’t do so here. What is this dead end you talk about?

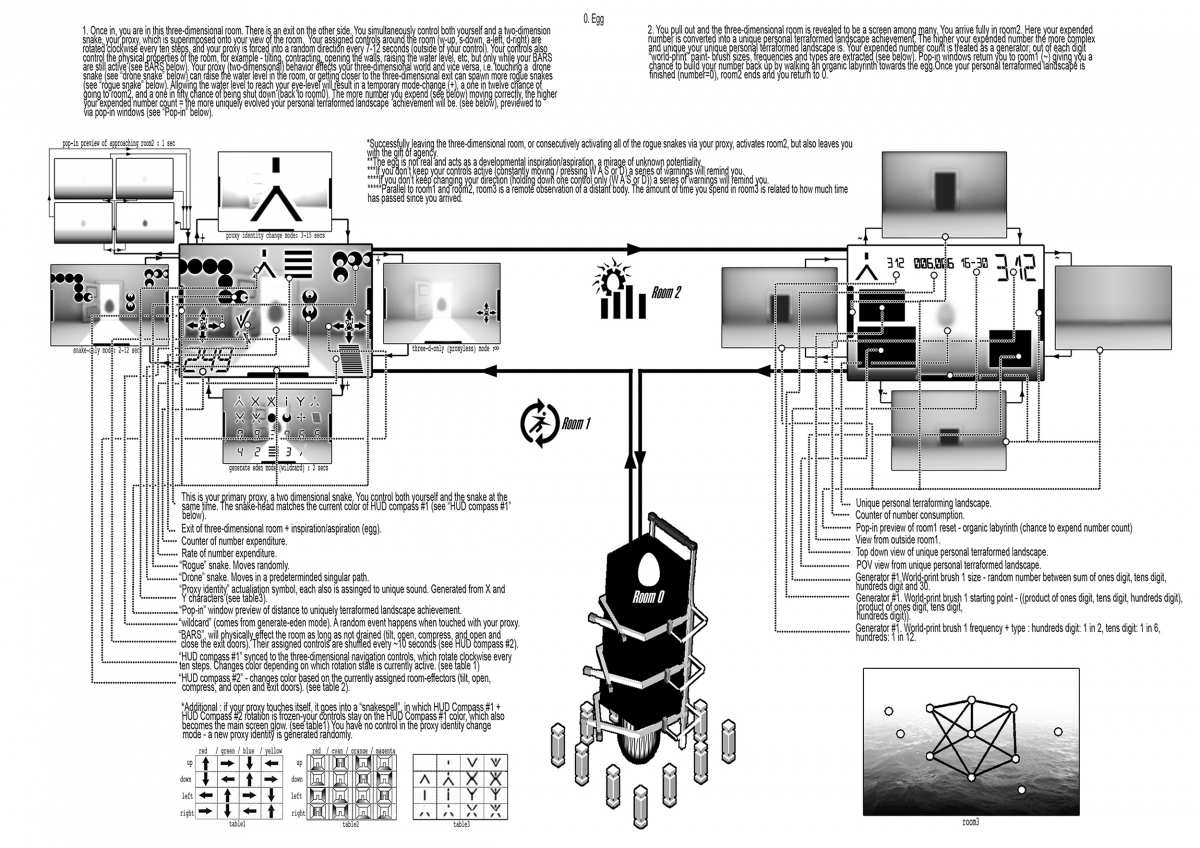

VT: I wanted to work with a confused cause-effect relationship, not something that’s normal for a game. Usually there’s a purpose, a scoring system, a win or a loss. It’s not so much that I wanted to program failure into the game, but to induce a kind of doubt: do your actions have the intentions you thought they would have? You press forward, but end up moving right, etc. Then your avatar moves by itself, as if it’s controlled by another force. Then you’re given just a bit of straightforward agency once again to get you to believe that before it was maybe just malfunctioning. Then, again, it flips, and you might cast doubt on whether your newfound agency was the malfunction. And if you pause your interaction, an alarm informs you that you have to keep pressing buttons, even if you’re not sure what you’re doing. So, basically, you’re in a constant state of confusion, distraction and alertness. The essence of the game was simply about getting out of a room with a single exit. Moving across this room initiates a whole labyrinthine process of two-dimensional snake proxies, walking in squares, tilting floors and contracting walls, rising water levels, etc. Oh, and it comes with a guide, which is also an adventure to read.

Instructional guide for ‘Proxyah v2’ hosted at Jupiter Woods, London.

ZO: Perhaps you’ve been in a room like that before? As we get older, it happens less and less often, and we have to make space or even push for such events or encounters. Maybe it’s the adult brain that just assumes nothing will happen, or simply nothing magical. It’s easy to take such a jaded view of things.

VT: Right, exactly, you need to keep making space to make space for it. The recent episode of Expanding Mind touches on precognition: experiencing something that you already know is going to happen. You retroactively cause it to happen, because you’ve already lived it. I’ve been thinking that maybe that’s what drives my work sometimes, already having seen or done it, which is why it has to be so particularly specific.

ZO: A déjà vu kind of moment?

VT: More like you know something’s going to happen, so then you cause it to happen. What’s interesting is that in the podcast, the interviewee was saying that this precognition is not based on objective reality, but on your own experience of reality instead. So, basically, your future brain is having a conversation with your present brain.

ZO: Mmm, I see … So, thank you very much for guiding me through your individual reality. I believe we’ve come to the end, or at least a calm zone, without failing, or ending up in the water. That’s a win already!