Kaspars Groševs. Photo by Zigmārs Jauja

The art critic Valts Miķelsons talks with Kaspars Groševs, artist, curator and co-founder of the Riga-based 427 contemporary art gallery

Valts Miķelsons: A while back, together with 427, you participated in the Supermarket Art Fair, which is an art fair for artist-run galleries. How was it?

Kaspars Groševs: Awful (laughs). I’d rather not expand on the subject, but I did learn that it wasn’t really the place for us. The context they operate in there doesn’t really correspond to how we perceive ourselves here. It seems that an artist-run gallery means something different in Scandinavia: often it’s a place run by artists, where its members also exhibit their work, much like the Artists’ Union of Latvia. We don’t work in that way, and we don’t want to exhibit ourselves.

That’s one of the reasons why I’m curious about this question: what does an artist-run gallery mean to you?

For me, personally, it was the time when I wanted to have a go at being a curator, to try and put together an exhibition for others, to combine different elements, works of art, ideas and artists, and to see what comes out of it all. To transport locally the fact that there is a place missing, where its creators, instead of relying on the circumstances by which whoever applies gets to exhibit, could engage in a mindful selection about how to steer the programme. Well, yes, in a way it means taking back control, and deciding on the content yourself. It’s like the time when the first video cameras emerged: you could show your own content on television. Similarly, once you have set up a gallery, you can quite frankly put whatever you wish in that space.

But then it’s clear that in your case this specific, fairly fixed place is highly important…

No. It’s like a point of reference. Now I’m beginning to think it expands beyond this space. The fact that this concrete place exists means you have to carry out activities on a more or less regular basis, and to actually do something there. In a way, the place forces you to think ahead, to always plan your agenda. It’s an anchor of sorts, which you can use if you decide to work on a publication next, or to put on a larger event elsewhere, or to sail out.

I imagine a certain role is also assigned to purely material, practical considerations, since, after all, this is a place…

In theory, the financial system we have allows us to secure this space somehow. It all depends on you what’s good and how much you can do in this place. Foreigners are often surprised that we organise so many exhibitions. While other places can only afford to have three or four shows a year, we end up with seven or eight.

Evita Vasiļjeva “Nothing Lost, Nothing Found”. Exhibition view, 427 gallery. Photo by Līga Spunde

Evita Vasiļjeva “Nothing Lost, Nothing Found”. Exhibition view, 427 gallery. Photo by Līga Spunde

Īrisa Erbse “Fermentation”. Exhibition view, 427 gallery. Photo by Līga Spunde

I’m thinking about the criteria here. I re-read your earlier interviews from the time when 427 opened, and at that time both you and Ieva Kraule (the co-founder of the gallery) were considerably less specific about how long 427 would last. There were ideas that 427 (four to seven) meant not only the gallery’s opening hours, but also its potential lifespan. Either in months or in exhibitions. Do you see it now as a long-term project?

Initially, it wasn’t clear at all whether we’d even get funding, because the first few exhibitions were put on using our own private means. We didn’t know how it would work out, although now it seems that this is not yet the end. Everything depends on external factors, such as money, of course, and on our own lives. At the moment, Ieva is living in Amsterdam. But it has not affected the work of our gallery in any particular way so far, because I’m still here. However, it remains an ambiguous organism at all times. And that’s why there’s so much freedom, because the minute we get bored, we can say ‘OK, enough, let’s stop.’ So far, we haven’t got bored.

Then perhaps I should ask a more direct question: for you personally, as well as in an institutional context, what constitutes a valuable, meaningful activity to you, while looking back at these years? Considering that there’s no financial aspect to evaluate, profit, in its narrowest sense. How would you evaluate the work of your gallery?

I would simply and rather subjectively look at whether I have enjoyed doing it all, whether the end result has been good, in my opinion. Well, not only in my eyes, but Ieva’s too. Every now and then, we discuss what has worked well, and things that haven’t. When you also realise that these things inspire or delight someone else, that’s wonderful. So far, the feedback has been very positive. For me personally, it’s interesting to see how the programme has slowly developed, to follow artists who have exhibited here, and to see what they do next. All of it, quite simply, creates a sense of fulfilment, seeing that artists continue to work. Wanting to be part of an organism that is art, not just locally but also internationally, which is why we work a lot with foreign artists.

How significant is the fact that the gallery is in Riga? Could it be located anywhere else? If so, what would be different?

As I mentioned once in an earlier interview, in Berlin, for example, we’d be one in a hundred. And in order to do something new there, you have to work with the local context. But here in Riga, basically, there’s a greater feeling of hunger, and not enough places and things happening. And at the same time, this also sometimes determines the programme. For example, to introduce something that’s lacking here but is normal in Berlin.

Well, I certainly don’t want to see myself as some sort of Riga patriot, but I live here, and I don’t really intend to move anywhere else; and basically, as a resident, I miss certain things that aren’t happening here.

Your comparison with Berlin suggests that the conceptual line taken by 427 is so far rather a rare thing in Latvia, and we can discuss this, perhaps already worn-out, comparison with Kim? But is it safe to conclude that Latvia already has a scene for such noticeably contemporary, conceptually oriented art? And does that not imply to some extent that the work of 427 is somewhat educational? Assuming that there’s a shortage of such things in Riga.

I don’t know if there is a scene. Perhaps it’s forming slowly. Even just as a result of having widespread access to the Internet, and now everyone follows developments elsewhere, and perhaps they also slowly align themselves with the Western discourse, I don’t know.

It seems to me that we’re not quite like Kim? But we value their work of the past few years highly. As an artist, I’ve benefited immensely from their work. We’d like to have such influence, perhaps on a smaller scale, to bring about something similar with our own work. At the same time, this is a rather selfish project, because as an artist and curator, I’m basically having an interesting time. But, back to the issue of education, I think that’s certainly the case. I’d like local artists to become more interesting and diverse.

Do you see any conceptual, strategic differences in what you’d like to do with 427 in comparison to Kim? Do you see it more as a symbiotic relationship? Do you sense any competition?

No, I don’t feel any competition at all, but the main difference is that we always feel we have more freedom, and we can afford to make mistakes time after time, and so on. We experiment more. For example, the fashion show Invisible Field which took place in March, and was a completely free event for one night only, it happened almost spontaneously without much prior preparation.

Hmm. You mentioned media which are sort of essential or perhaps not. Your gallery recently hosted several exhibitions of paintings, including work by Raidis Kalniņš, whose work, from a traditional point of view, could be classed as ceramics…

I’ve lately become more and more drawn towards painting. Ieva works with ceramic and sculptural forms. But I’m very interested in painting in its own right, for example, and to me this seems to be educational work in our local context, to find the sort of painting that is not typically Latvian, traditionally grey, romantic, semi-realistic. We have had very little of the so-called new media in our exhibitions. These have mostly been sculptural, spatial objects, installations, and the mentioned ceramics.

Vicente H.J. Mollestad “CGDGCE”. Exhibition view, 427 gallery. Photo by Līga Spunde

Kaspars Groševs. Photo by Elīna Vītola

You occupy simultaneously two roles, curator and artist, that have traditionally been kept apart. Do you also separate them yourself? Are you sometimes a curator, and other times an artist? Could you, for example, curate your own exhibition in a gallery?

No, I’d rather not organise my own exhibition in a gallery… Although, to some extent, I’ve already done something similar. I think my work as a curator corresponds rather a lot to what I do as an artist. And that group show I worked on for Kim? ‘Exit, Stuttering & Nebula’ was predominantly my attempt to be simultaneously an artist and a curator, basically by using the work of another artist as if it were my own.

Also, my work with sound to some extent relates to what I do with drawing and painting; and what I then do as a curator, perhaps somehow connects to it all, or maybe it’s just an addition. I’d prefer it if there was no schizophrenic divide between things, but for them to slowly intertwine with each other.

As an artist, how do you perceive the role of a curator? Do you think curators interfere arbitrarily with your work? Or, on the contrary, do you find it all interesting?

Well, I guess it depends on individual curators. There are some who simply collect together a few artists, and then orchestrate the necessary circumstances for the exhibition to take place. And then we have curators who get actively involved in whatever the outcome will be, and I find those most interesting. Of course, there must be mutual acceptance: you have to be prepared for someone to interfere in your work. My work is fairly open, and allows for various possibilities of execution, which is why I always find it interesting when someone else joins in with their own ideas. That’s why I wanted to become a curator, because it seemed there was a shortage of people in Latvia who could work in a more creative, liberated way.

It seems that 427 tends to work rather a lot with Lithuanians, and perhaps less so with Estonians. Why’s that? Aren’t there enough Latvian artists? Is it because of the similarities in politics, ideas and temperaments?

Well, a bit of everything. My relationship with Lithuanians got off to a good start after a summer camp in Žagarė quite a few years ago, where I met a lot of pleasant people, all of whom were artists. Also, Kim? occasionally presented a few Lithuanian group exhibitions here. And then I started to follow events there a bit more. It seemed to me that, in terms of ideas, there was more happening that I found interesting. According to Matthew Post, an American curator, every other person in Lithuania is unusual, a character. In Latvia, we have fewer of these characters. Everyone is somehow striving to be more normal than they actually are. Unfortunately, Lithuania doesn’t support us financially, although we surely deserve some sort of award for promoting Lithuanian culture!

We’ve talked a lot about Latvia, what we already have here, and what’s still missing… but, how do you see 427 in a European context? And does it even matter?

Internationally, it seems to me, we’re quite hazy, we don’t just operate inside a particular niche, we allow ourselves to be more liberal and to experiment, to try one thing, and then another… What we see in the largest European cities is that art galleries are more ‘niche-like’. It’s hard to compare, simply because of geographical distances, however we are in Latvia… I don’t know. Sometimes I try to guage from our foreign visitors how we might come across, but that’s not always possible. We think we’re not just a local institution, a place. We also fit into a wider context, and that’s also interesting to someone who visits from, I don’t know, Germany or France or England.

Do you see people like that?

We meet them, yes. When a foreign art critic, professional or art worker arrives in Latvia, well, they don’t really have that much to see, and also when I travel, I’m always interested in those smaller places, and not just in the official opinion, represented by, let’s say, a museum or a contemporary art centre. I’m also quite drawn towards the vibrant processes that happen in smaller places, where something quite strange is often exhibited. And likewise, foreigners come here looking for an alternative angle on the local art scene.

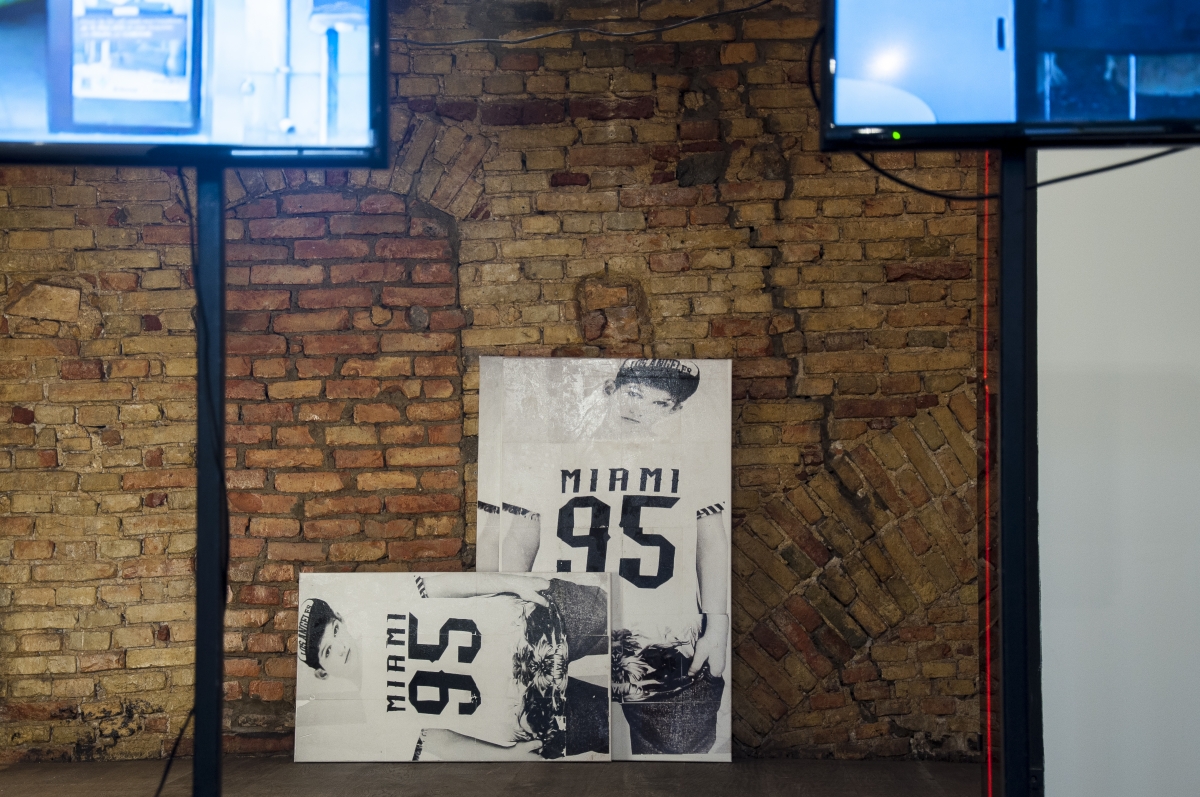

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy “Princess PomPom in the Villa of Falling Flowers”. Exhibition view, 427 gallery. Photo by Ansis Starks

Group exhibition “Joy and Mirror. Port City”, 427 gallery. Photo by Līga Spunde

Gili Tal “Agonisers”. Exhibition view, 427 gallery. Photo by Kristiana Marija Sproģe