I became aware of the work by the artist and writer Amira Hanafi (USA/EG, b. 1979) just after her exhibition ‘The Science of a Good Lie’ opened at the Sodų 4 project space in Vilnius (it ran from 25 October to 9 November 2018). I remember seeing the photographs from the opening, and thinking about its intriguing title. The exhibition prompted many more questions than answers to my initial interest. It presented diagrams and images from Hanafi’s research during her residency at the VDA Nida Art Colony in September and October 2018, based on the fake memoir by LoBagola. Is it not especially relevant to us, who are familiar with the idea of story-telling and creating fake histories from our Soviet past?

Karolina Rybačiauskaitė: As an introduction, could you tell me more about how your artistic practice has developed up till now? I’m curious about what kind of medium you started from, and how you became interested in research, in other people’s lives, so to speak? Is it motivated by reasons other than your previous practice? What does research mean to you after all?

Amira Hanafi: It would be no exaggeration to say that I spent most of my childhood reading. I also wrote, keeping diaries, writing stories, and later poems. I was fascinated by the word in all its forms. I made crosswords, and I tried to write a story that was a palindrome. I copied the calligraphy I saw in mosques and which hung in my home. That is to say, language was my first medium of expression, and it remains central to my practice even now.

I studied poetry at college, using it as a cathartic channel, as young people often do. Later, I became bored with my own voice echoing back at me from the page. I started bringing other texts in, and making visual poetry. One of my first experiments in that vein was a poem, which has long since been lost, weaving quotes from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights into my own writing. Later, I was introduced to conceptual writing, which had a profound influence on my work.

The possibility of other people’s words becoming my own, the possibility to put other people’s words into my mouth … that opened up a lot of space for me. I went on to study writing at an art school, and came to see myself as an artist as well as a poet. It allowed me to work with language in different and multiple forms.

Your question about research is a difficult one, because I think research might just be a personality trait of mine. I’m always asking ‘why’. I’m dogged by an insatiable curiosity, and plagued by endless doubt. I want to know not only what people believe, but also how they came to their beliefs, what logic they follow to assert themselves in the world. Part of this preoccupation with other people’s lives stems from my own fluid identities. As a mixed person, my body contains dualities that most people do not readily have the space to accommodate. My research is a way of building community around me that reflects the differences I contain in myself, without the tired sense of tragedy and impossibility that has long been felt by those who belong to more than one culture or race.

My work is a way of exploring and expressing my hybridity, through the repeated writing and rewriting of my stories, or histories, which necessarily include others. Language is material, and I understand it in a Bakhtinian, dialogic sense. When I use words, I participate in a continuous interaction with others which constantly shapes and reshapes meaning. My works try to make that process visible, and sometimes they take the process itself as their subject.

Amira Hanafi. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Amira Hanafi. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Karolina: Could you elaborate on the idea of your fluid identities? Is it only about hybridity in terms of culture and race, or is it also about instability and the ability to resist being fixed? I’ve read that you are interested in ways people in a diaspora inhabit their hybrid identities. I wonder what you think of inhabitance, and the possible inheritance of identities in our contemporary world?

Amira: I talk about fluidity in navigating the knotty structure of a mixed and intersectional identity. It’s not restricted to culture or race. I am a mixed Egyptian, a diasporic African woman, a US American descended from Germans who lived for several generations in Russia, the child of a brown parent and a white parent, a person of colour who is read in many contexts as white, a dual citizen who grew up in the only Muslim family in an affluent part of New York and who now lives in a country where I was not born. This list is not exhaustive, and it can be reorganised. When I make a claim to inhabit my plural identity, I am making a claim to include my narrative in the foundations of the multiple groups in which I find myself. It’s an exercise of power in the politics of naming my social locations.

I use the word inhabit in the sense of ‘having one’s home in’, and understand identity groups as ‘potential coalitions’, as Kimberlé Crenshaw articulates them in her 1991 essay on intersectionality. ‘With identity thus reconceptualized,’ she writes, ‘it may be easier to understand the need for and to summon the courage to challenge groups that are after all, in one sense, “home” to us, in the name of the parts of us that are not made at home.’ My definition of home is itinerant. My artistic practice reflects this fluidity, a resistance to being singularly categorised.

Karolina: When talking about the possible inheritance of identities, I didn’t want to presume the singularly categorised ones. I use the word ‘inheritance’ in order to think about the notion of belonging; about creating a collective intelligence through time and the density of historical experiences, and learning with it. I think that in the current discourses of posthumanism and transhumanism, we often have two quite radical and problematic suggestions for these matters: either we should concentrate on situating ourselves for acknowledging what surrounds us, or we should pursue our nomadic aspirations and go and colonise outer space. While trying to be critical of it, I’m curious what you think about it, having such a plural identity?

Amira: Neither of those suggestions seems radical to me. The proposition to abandon history and go and colonise outer space makes me laugh! What could be less ahistorical than colonialism? Situating ourselves to acknowledge what surrounds us is inevitable. History is inscribed in bodies, not a separate animal we look to and learn from. Especially non-European bodies live history, live the effects of colonialism’s violent encounters with difference. There’s growing evidence that trauma can be passed down genetically; there are stresses from structural and institutional inequalities that are manifested in people’s bodies as disorders, disease and early death. The work I’m doing now is thinking through the ways in which history has been narrated to me, seeking out erased narratives, and looking at how people live lives in unreported gaps.

Karolina: I assume that one example of this work is your current project about the fictional memoir of Bata Kindai Amgoza Ibn LoBagola, which was recently presented in the Sodų 4 project space in Vilnius. I know that you were also working on this project in your residency at Nida Art Colony this autumn. Firstly, I’m curious why you decided to work with LoBagola in Lithuania. Was the environment at Nida useful in any way for the aims of your project? Secondly, could you tell us more about this research? How did you find LoBagola’s memoir, and why did you decide to work with it? What stage of the research did you present at Sodų 4? Are you planning to work on it more?

Amira: Yes, my current work is with the memoir that was published in New York in 1930. LoBagola was an entertainer and storyteller, who performed as a native African for audiences in the USA, the UK and Europe. Through his performance, he also came to work as a sort of cultural informant at a time when anthropologists were beginning to seek out native informants. The story he tells in his book is a spectacular narrative about growing up in West Africa in a multicultural tribal society, his description of which is a pastiche of different descriptions coming mostly from Western writers. As a young boy, he wanders off in search of the white man, who has never appeared in his village, and through a series of adventures, ends up being raised in Scotland as a companion to the son of a white family. Thus begins a story of world travel that ends in the United States, where he was actually born in 1887, in Baltimore.

I came across the book on a short residency at the Bibliothek Andreas Züst in Switzerland in 2017. I was struck by how Eurocentric the collection was, and after a devastating encounter with a book of photographs of lynchings in the United States, I left the library for a day or two. When I went back in, I wanted to find a book about Africa written by an African. On the short Africa shelf, I found LoBagola: An African Savage’s Own Story. I wasn’t too far into the book before becoming suspicious of the veracity of the story, and a quick Google search told me that LoBagola was an ‘impostor’. I was drawn to the persona because at the time I was questioning the way in which I was performing Egyptian identity when presenting my work in the USA, the UK and Europe.

Although LoBagola’s book had been on my mind, I started working in earnest on research in Nida. I didn’t choose specifically to come to Lithuania; the residency was offered as an exchange for an Egyptian artist, and is part of a larger European project dealing with some of the issues that my work addresses. It’s part of the economy of being an artist, I think, travelling to do work that I might otherwise do at home. I don’t usually take residencies as a chance to work on the place I’m visiting. For me, to make informed work that raises vital questions, I have to, I’ll use the same word, inhabit a place, find a home there. Nida is a landscape to which I am foreign. It offered me a great space to focus. The remarkable natural features of the Curonian Spit gave me a chance to recover my energy when I needed a break from reading, which is what I spent most of my time doing.

The research is focused around two things: reconstructing the events of LoBagola’s life as it was lived outside his memoir, and identifying the references he makes in the book. He was clearly well read: he makes references to slave narratives, African American folklore, and nineteenth-century travel writing on Africa, to mention just a few. I began to understand that I am taking LoBagola as a kind of guide through history. Walking alongside him, following the labyrinthine paths of his text, I encounter a different history of the cords between Africa and the Americas, different to the one I had been taught as a child in the US, or encountered in the last decade living in Egypt.

The work at Sodų 4 in October is an introductory chapter for an ongoing project. For me it’s a way of posing some questions: What does it mean to take as a guide through history this performer, whom I’ve read referred to as ordinary, a failure, and an impostor? How does one read history with an awareness of fiction as an essential element of its telling?

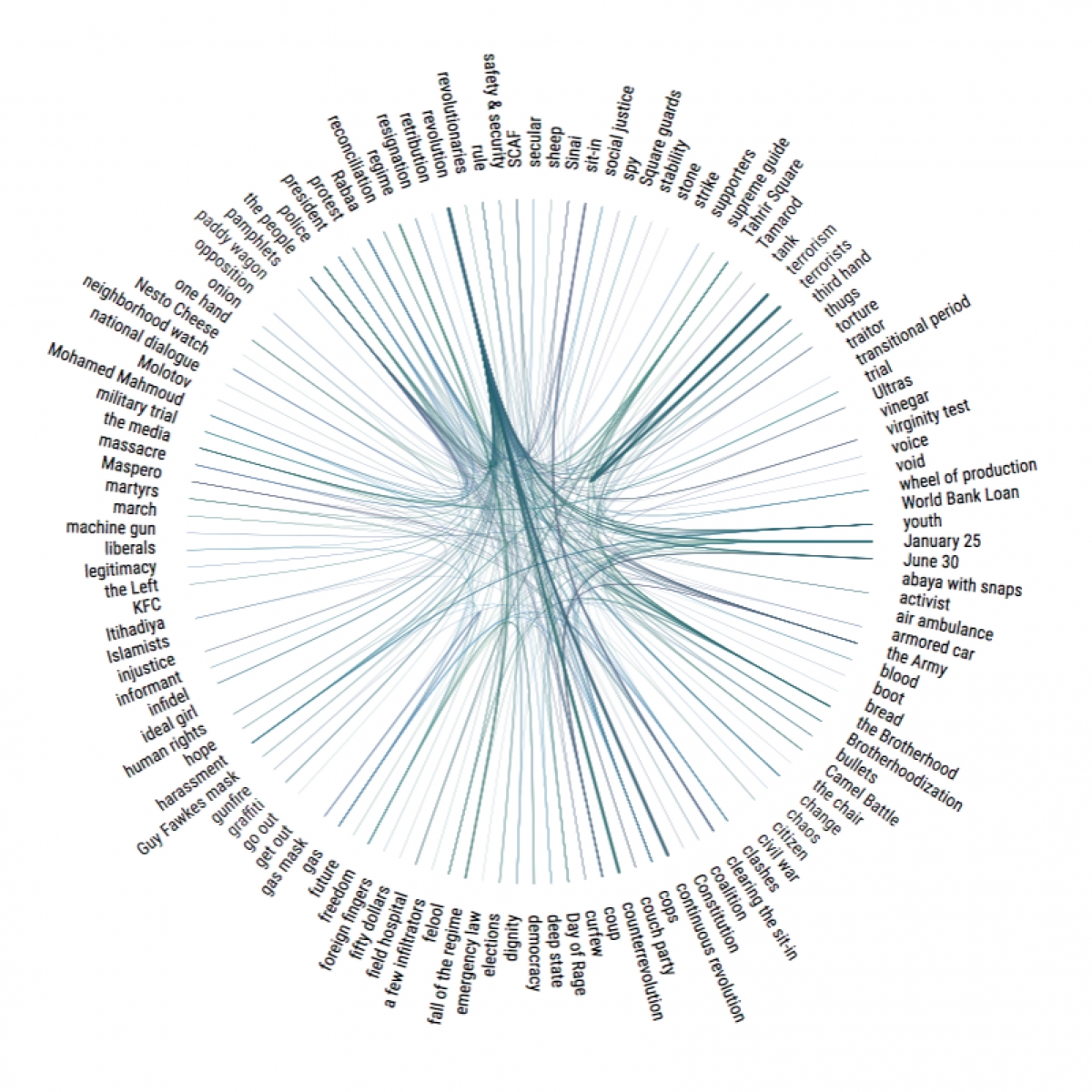

A dictionary of the revolution, digital publication http://qamosalthawra.com (2018)

Karolina: What about the visual part of the exhibition? How do you connect the story by LoBagola and your own storytelling practices? What do you think about the results of artistic research as such? Is it in your case the questions you are asking as an artist, or could it be something else as well?

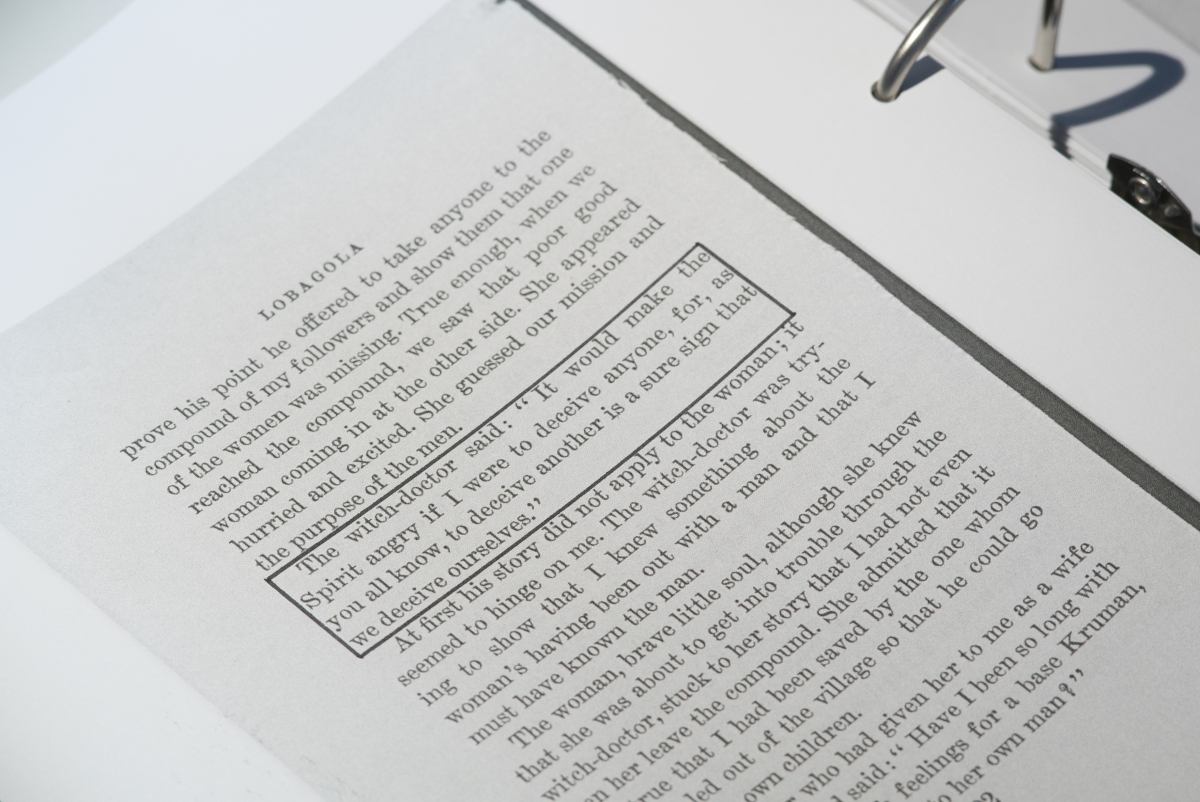

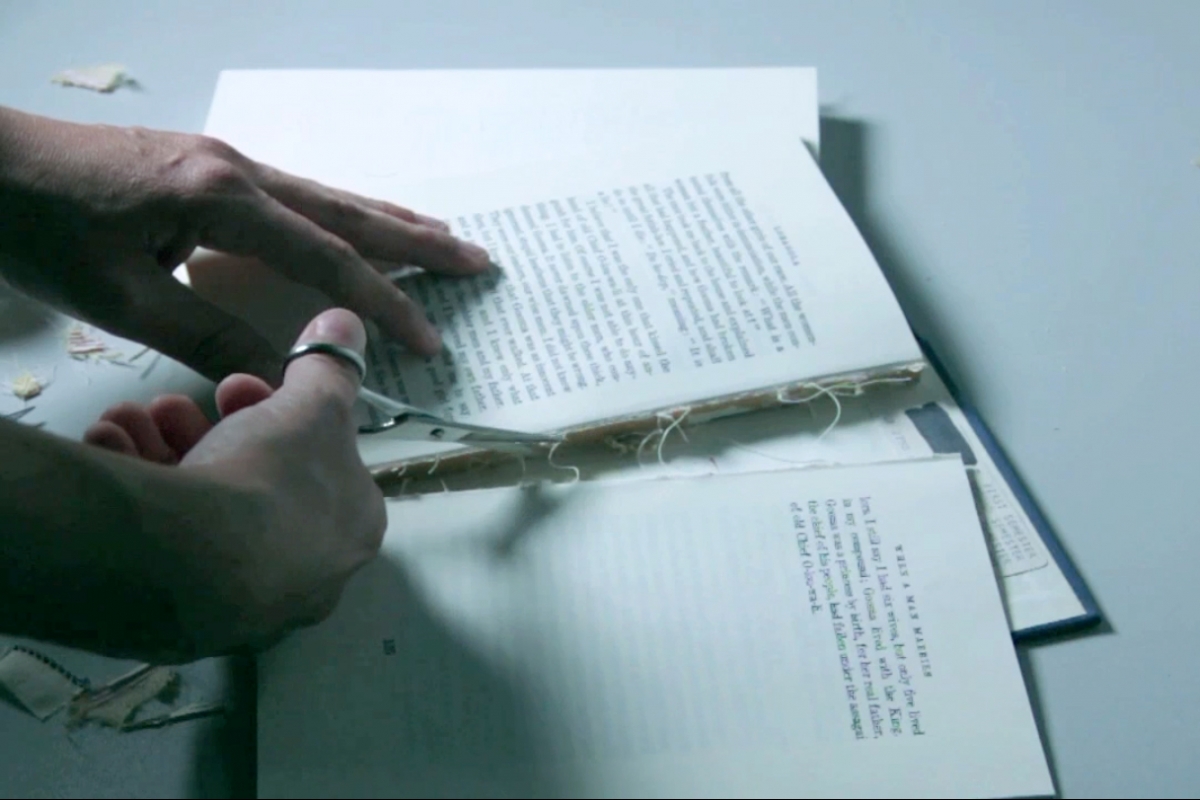

Amira: In the exhibition, I present a reading of LoBagola’s text as a large diagram, based on a grid of pages in the book. Fine lines printed on tracing paper frame each section that makes references to truth/fiction. The text is absent. You have to come close to see that there is an image at all. The approach towards the image embodies the tension between deception and what people believe to be true. In another part of the gallery, there is a marked-up copy of the book, and a video in which I unbind the book with surgical instruments. The video creates another kind of tension, a violent act of close reading.

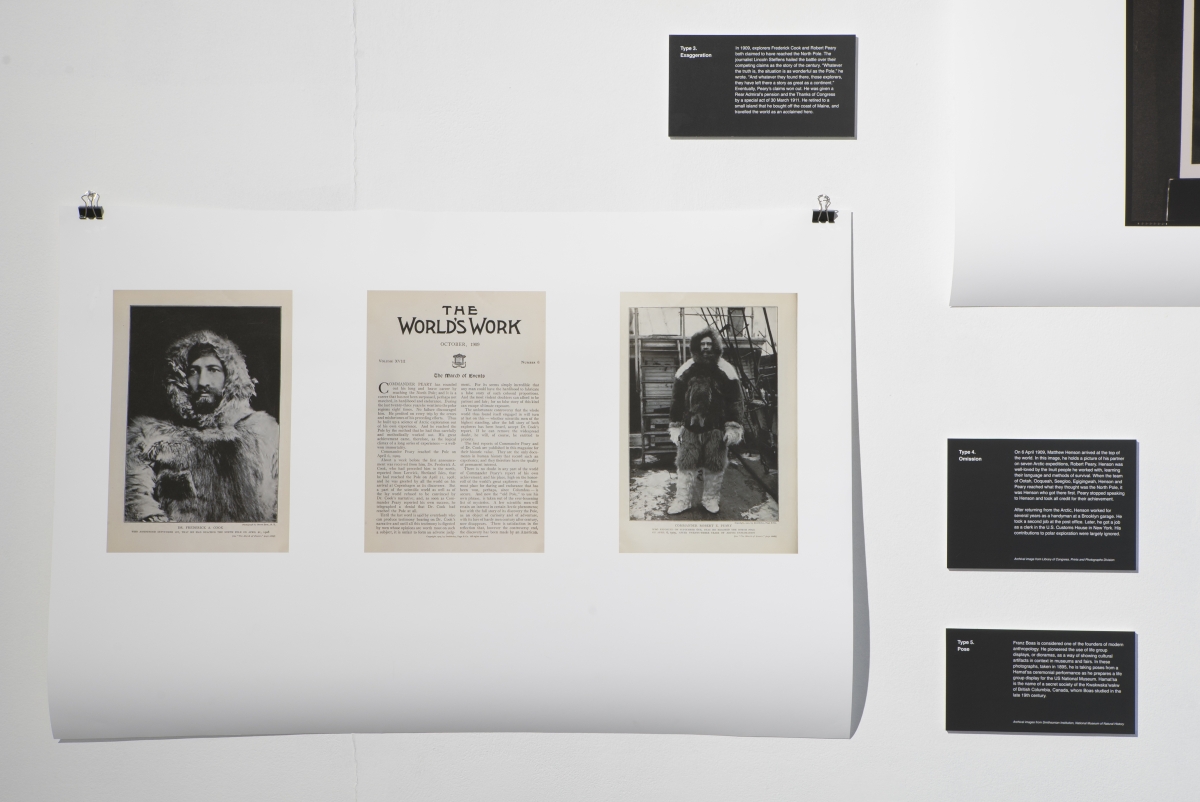

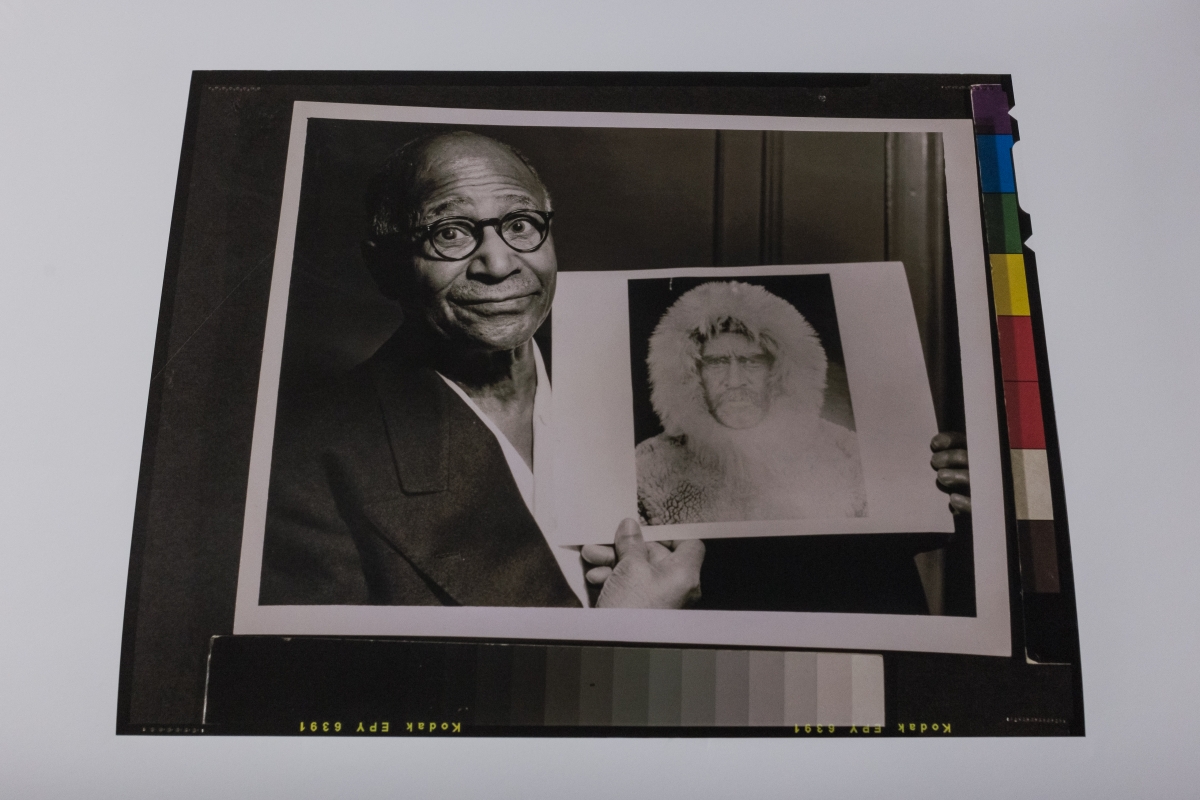

On the third wall, archival material and labels that mimic the display in an anthropological museum tell a story that starts from one sentence in the book: ‘Think of Admiral Peary and Captain Cook!’ They were explorers who both claimed to be the first to reach the North Pole. Through their story, we encounter others, such as Matthew Henson, Peary’s black US American partner who was long erased from history; the renowned anthropologist Franz Boas, who requested that Peary bring ‘a middle-aged Eskimo’ back to New York from his travels; and Qisuk, who dies while living in the Museum of Natural History, and whose bones are kept there for another hundred years. Together, the material offers different readings of types of deception in the telling of history.

Earlier this year, I finished ‘A Dictionary of the Revolution’, a series of 125 texts woven together from transcriptions of conversations held in Egypt in 2014. I witnessed many documentary projects unfolding in the three years after 2011. All the projects appeared to engage with a similar, overlapping group of people. For the dictionary, I wanted to seek out people outside those circles, to document in other spaces.

The texts I collaged together using nearly two hundred voices are noisy, and full of stories, opinions, contradictions and lies. After I published the book-length project as a website, I wondered how people would read this muddled story of events. Which parts would they believe? How much of the text did you have to read before coming to realise that this was a plural voice containing many truths and fictions? Is it a plural voice, or is it my own? How can the pronoun ‘I’ be plural? What separates the dictionary from established modes of historiography? Is every attempt to understand violent?

Although I use other voices in my work, I speak with and through them. By putting their words in my mouth, I change them and change myself. They and I are present, my life with others. I try to make these processes visible, and in this sense my work is memoir.

Truth and deception are major themes in LoBagola’s memoir. I read his text exclaiming: ‘I’m telling stories, these are lies, and yet you believe me. See who believes me!’ After the book’s publication, he was invited to tour and lecture and participate in public debates. Some reviewers expressed scepticism about his authenticity, but most commented on how entertaining the stories were. They helped the book sell. One reviewer called it required reading for missionaries in Africa. The only academic Africanist to review the book was Melville Herskovits, whose scathing review in the Nation condemned the publisher for spreading damaging falsehoods. But that didn’t stop the book from getting into public and university libraries as non-fiction, where it is still shelved today.

The Science of a Good Lie, Amira Hanafi, Sodų 4, Vilnius. Photo: Laurynas Skeisgiela

Karolina: Do you have more companions for reading histories with? Maybe from your other projects? Besides, what about those who are with you in the process of doing research? Does travelling through different residencies in various parts of the world make it a less lonely experience, or maybe the opposite? What do you think in general of this kind of ‘economy of being an artist’?

Amira: I’m not especially lonely, at home or elsewhere. I’ve always found plenty of companions in reading. One of the things I’m working on is putting together a library of texts I encounter through my reading of LoBagola. The library is a space for a community of real and fictional characters to meet. A visitor can come to the reading room and spend time with them, and with me.

I’m pretty realistic about the economy of being an artist. There’s the work I do, which, like many artists, I do because I feel compelled to, because I love nothing more than learning and making. At the same time, I understand that in order to sustain a practice, I have to find a place in the art world as it exists, or create other opportunities to share my work. It’s a balancing act in deciding where to put my energy, and I can’t say yet that I feel very virtuosic in that respect. But as long as I define success as having been able to sustain a practice so far … to not have quit … and to make the living I can from the work I want to do, I’m successful. Travel is actually a great part of the job. New places and people are inspiring, and I’m especially excited when I get to travel somewhere that’s outside the USA or Western Europe. I’m really glad to have come to Lithuania, for instance, much more so than, say, the UK or Switzerland. It’s not just about the parallels and differences I see between the Baltic and the region I live in, but the possibility of making connections that don’t reiterate the centralisation of the art world.

Karolina: Thank you!

The Science of a Good Lie, Amira Hanafi, Sodų 4, Vilnius. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

The Science of a Good Lie, Amira Hanafi, Sodų 4, Vilnius. Photo: Laurynas Skeisgiela

The Science of a Good Lie, Amira Hanafi, Sodų 4, Vilnius. Photo: Laurynas Skeisgiela

The Science of a Good Lie, Amira Hanafi, Sodų 4, Vilnius. Photo: Laurynas Skeisgiela

The Science of a Good Lie, Amira Hanafi, Sodų 4, Vilnius. Photo: Laurynas Skeisgiela

The Science of a Good Lie, Amira Hanafi, Sodų 4, Vilnius. Photo: Laurynas Skeisgiela

The Science of a Good Lie, Amira Hanafi, Sodų 4, Vilnius. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko