Treasure hunt is a game where each player tries to be the first in finding whatever has been hidden, using a series of clues and directions, but mainly counting on their imagination. Searching for artists, who work with the Soviet traces after more than 20 years of period during which almost whole generation has been brought up since the collapse of the Soviet Union, we sometimes felt like those hunters from the game. Not that there would be lack of the traces or artists in general, but as we started off in Latvia, we realized that this is a rare topic here. Moreover, it is mostly taken up by chance or treated ironically, in a kitsch-like way. The traces of the Soviet as such in Latvia as well as in the area of the Eastern Europe, post-Soviet and post-communist countries have merged with our current social and economic realities, political and religious contexts, which reshaped them in our personal and collective memory. On the other hand, the topic has been exploited largely during the last decades in different exhibitions and projects all over the world. Is it possible then to reveal something new in the game?

While part of Latvian society would gladly let the Soviet relics merge and disappear, we wanted to bring up the “treasures” that are underestimated either because of falling into a hole of collective amnesia (due to ideological charge and painfulness of memories etc.) or sinking in a semi-sweet nostalgia of the „good old days” when everyone had a job and the big mother state took care of us.

Flying carpet and modernism

Taking all of this into consideration, the project „Revisiting Footnotes”, organized by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, tries to avoid the aforementioned attitudes and to search for new interpretations in the area of the post-Soviet. For example, the artist Žilvinas Landzbergas is putting the Soviet narrative told through an ordinary carpet next to the idea of the failure of the modernism (Fast Forward, 2013).

Žilvinas Landzbergas, Fast Forward, 2013

Artist does not, however, want us to see this explanation as the only one. It makes me think about the issue many contemporary theoreticians have tried to define. It is the way in which the post-Soviet condition relates to the modernism. There are several conceptions – some assert that modernism comes directly after the collapse of the union, the others – keep to the idea that modernist ideas were at work during the Soviet time, but differently from the other side of the wall (Susan Buck-Morss, Boris Groys). Post-communism is then a postmodern condition.((Simon Sheikh, What Remains? – Chto Delat?, Post-Communism and Art. Published at the catalogue of Chto Delat? solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Baden-Baden (Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, Cologne, 96 p., 2011).)) There is other way to read the work as well. The carpet used in the installation is the (only) direct reference to the Soviet time, because it is obviously produced in the 80ties. The object itself signifies more than just the apartment decorated in the style of the late Soviet period, but also reminds me of a flying carpet from the oriental tales. If I let this fantasy continue, it leads to a souq((An open-air market in the Middle East, North Africa or Central Asia.)) somewhere in Samarkand (Uzbekistan). However, the brownish pattern and the level of deterioration reminds of the mass production and both – spoils the magic and is a “footprint” leading us the former (or contemporary) Central Asia.

While Landzbergas has a bit dreamlike approach to the topic, the work of Slavs&Tatars (Triangulation, 2011) is more direct. Its slogan “Not Moscow, not Mecca” is a reference to the foreign policy to separate the Central Asian population of the Soviet Union from Islam – “To Moscow, not Mecca”. This policy was meant at that time to decrease the impact of the religion on the Central Asians and strengthen the relation to the Soviet Union. After the end of the Soviet Union Russia’s role is still part of the main narrative of those republics((Inside Central Asia: A Political and Cultural History of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Iran)), but the Triangulation suggests playing with the possibility of being free from the bonds from both sides.

Slavs & Tatars, Triangulation, 2011

The idea of the “Revisiting Footnotes” project started as a reaction to the recently appeared term of “ostalgia” – a tendency to idealize the Soviet time by composing a romanticized version of the story. It grew stronger along with more time passing after the collapse of the union and reached the peak after the economic crisis. Then follows a sudden realization that the capitalism might lead to even greater upheaval than the socialism. Thus a necessity for new, inspiring future scenarios and new utopias arose. Socialism was based on the former utopian thinkers’ ideas and if it did not work as a whole, could it be that by revealing the footnotes, references and small details from that experience, a new scenario for the future could be built? One example suggesting this idea is the workers’ self-management in the factories of the former Yugoslavia (if we agree to broaden the scope towards more than only the socialist countries within the Soviet Union), is now actively discussed as a means of getting out of the rule capitalists in the big corporations in the US. As Noam Chomsky suggests in his book Occupy when the big corporation decides to close down a branch of a factory that is not profitable enough for them, to prevent people from losing their jobs, the best solution could be – to let them manage it themselves. Although there are some examples like this, it is not yet anything like a tendency. (Noam Chomsky, Occupy, 2012).

Transition as a point of perplexity. Socialism vs Capitalism

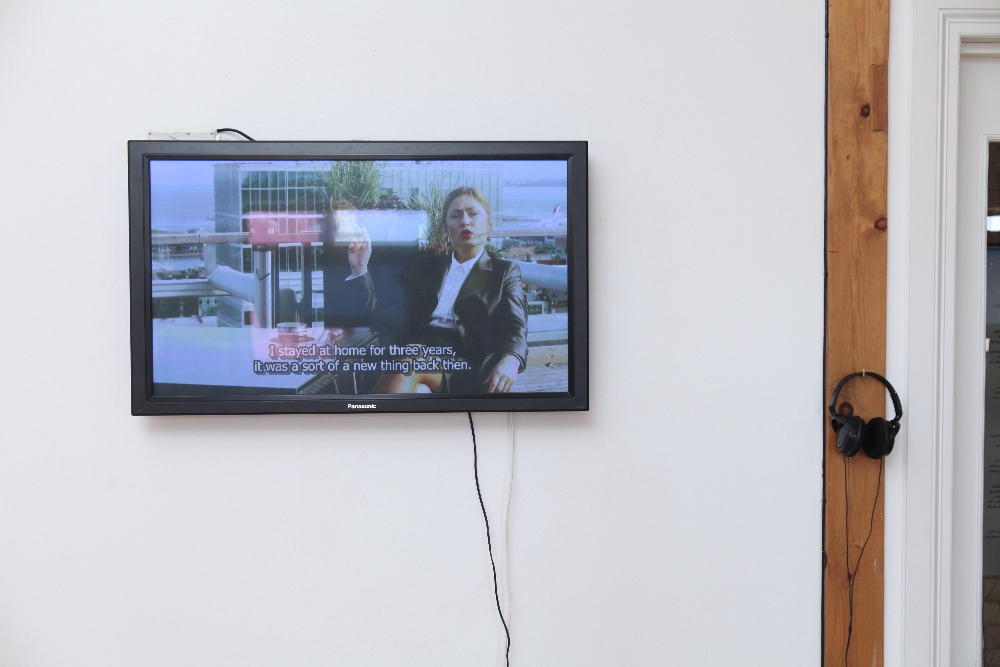

Looking into the past helps to understand the present. There are several artists in the exhibition that work with the comparison of then and now to make us understand the absurdity of the current state caused by the rapid changes from the socialism towards the capitalism. The disappointment after the political and economic transformation processes is reflected in the movie by the Estonian artist Marge Monko Shaken not Stirred (2012). It focuses on the issues of how social roles have been affected by the transition and different ways in which political contexts are manifested in the everyday life. Two main protagonists – an elegant businesswoman and an older dishwasher – lead their lives after the political and economic transformations. Each representing different social strata they tell one and the same story: expectations of the new, unlimited possibilities of individual self-realisation in the new economic system turn out to be an empty dream. The work of Monko shows that some of the most visible are the footprints left in the personalities of people. The personal stories reveal that the changes in the system demand for changes in the behaviour which are not so easy to achieve.

Marge Monko, Shaken not Stirred, 2010

Armenian artist Tigran Khachatryan is certainly conscious about the aforementioned changes and addresses them with a more ironical approach. He uses the fragments from the short film of Artavazd Peleshyan dedicated to the 50th anniversary of October Revolution (1967) and a documentation of everyday activities of contemporary youth. There is something in common in these shots capturing different epochs: both are based on montage aimed to convey “revolutionary” rhetoric, but at the same time there is a sharp contradiction – the post-Soviet “revolutionaries” no more fight against oppressors, but try to overpower each other. A thing that could be made out of these two works is that we know what the system is (from our former “close relations” with the socialism and communism), how it works and what it causes, but unfortunately we don’t know (yet) how to get out of it (without a revolution).

Self-irony vs system

While heading home by a bus the other day and reading a book by Lithuanian artist Indrė Klimaitė On Continuous and Systematic Nutrition Development (2013) whish was a part of the show as well, I noticed a woman beside me browsing a self-help book in which Hanna and Benny reveal their miraculous achievements on losing weight. I will explain the associations I made. The work of Klimaitė is based on textual and visual materials collected from Soviet public catering books between 1935 – 1990 spanning over a broad range of documents, from official sanitation memorandum to archaeological photographs, plans for classification of potatoes, dinner room schemes, soviet gastronomy recipes and measures to fight rodents and microbes. The system formerly encompassing everyone’s regime – from a housewife to a food factory is persistently replaced by another system, one full of beautiful images and sweet promises making it even more deceitful.

The paradoxes of the public space of Ukraine appear in the installation Before. Now. Further (2009) by the artist Lada Nakonechna. A pencil drawing of the central square in Kiev (where the statue of Lenin has been replaced by a strange sculpture and a shopping mall) represents the past, while a current photograph – the present and a mirror at the corner of the display merges both images and creates an illusion of the future. The irony and especially the self-irony were important in fighting against or surviving in the Soviet system. Nakonechna continues to use it as a means when talking about the present state of Ukraine and its policy of the public space.

On “Friendship of Nations”

The Estonian artist’s, Kristina Norman’s, film Monolith (2007) outlines the conflict centered on the Bronze Soldier monument in Tallinn in 2006–2007. She states that through this film she wanted to stay neutral towards the issue. The work begins with a rephrase of the legendary film by Stanley Kubrick 2011: A Space Odyssey, similarly to its plot the Bronze Soldier lands on Earth splitting the society. Some adore this object and its cosmic origins, others – fight against it, demanding the “truth” till the end. The whole film, in my opinion, talks about the forced multiculturalism of the Soviet time and its remnants more than about the monument as such. It serves to bring up the situation where the Russian community in Estonia is always a matter of conflict, and a similar situation occurs in other Baltic countries

Kristina Norman, Monolith, 2007

Everyday objects and usual places as treasures

An outsider’s view on the leftovers of the past time is given in Studio Kapsēde, the work by Henrik Duncker. Not knowing the language, he found a way to connect with country – Latvia is the motherland of his wife – by taking pictures of it. As a result a portable photo studio (Studio Kapsēde) was at first set up in the living room of Henrik’s mother-in-law. It turned out that among the items stored in it were Soviet-time objects. Now Studio Kapsēde stand for a process that involves the artist choosing and photographing objects against coloured backgrounds; “portraits” of objects are complemented with texts by an art historian Iliana Veinberga and writer Maira Dobele. Perhaps a Latvian artist wouldn’t dare to put the backgrounds as bright as Duncker does, because this approach makes them lose their connection to the lousy interiors and Soviet history. It almost works as a re-creation of the objects visually. For me Studio Kapsēde acted on two levels – firstly, as a visual alienation of the object and its meaning, and secondly, still keeping thier historical and personal context with them through the texts that could be read in separate sheets of paper piled next to the pictures.

A mixture of personal observations and a comparative study is represented in a photography book by Aija Bley Oldcool (2013). It shows, first of all, that it only takes to get a few blocks away from the city centre or set off to the countryside for all the “treasures” of the Soviet time to begin overwhelm you by both their exoticism and sad desolation. Most of images are captured during artist’s journeys around the previously Soviet republics. Thus it is apparent that the Soviet period has left deep imprints in such geographically and culturally diverse territories – from Riga to somewhere as remote as a Central Asia – which though even the most attentive spectator could not discern because of the unified features of these signs.

Different levels of the post-Soviet

The participants of the exhibition represent a broad and heterogeneous region with different levels of overcoming the Soviet past. What had already become a topic of joyful exploration by Latvian artist Kate Krolle and curator Maija Miķelsone in the Soviet Table Culture Workshop performed in the framework of “Revisiting Footnotes”, appeared to be still a current reality in Ukraine. Or while Latvians generally share a very pro-European, pro-capitalist viewpoint trying to avoid challenging the current state of things, much more revolutionary vibes come from Ukraine. In the symposium that followed the first exhibition, the artist Lada Nakonechna presented different projects and informal groups she is involved in (like R.E.S. Revolutionary Experimental Space, Hudrada etc.). The importance of this type of formal and informal gathering of artists and theoreticians reminds me of our first motive to start this project. It was a realization that the links between the former post-communist, post-socialist and Eastern European countries have gradually weakened since the transformation and rush towards making friends with the West. But what we have forgot is that we still have a lot in common that could help us to understand and be understood (not only considered exotic).

If not stilmulating to imagine a completely new utopia from the best of what has been left here since the Soviet times, then “Revisiting Footnotes” certainly intend to take a position towards our recent past, overcome the post-Soviet complex and take it as part of our current reality.

While working with the people who deal with the Soviet relics, a parallel story comes out revealing similarities on personal, management and other levels. Just like simply realizing that all of the artists in their 20s and 30s had a 6 year age difference between their siblings, made us come to a quick conclusion that this could well be a typical Soviet trait. Shall we search for an explanation for that?

“Revisiting Footnotes II” is on view in the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art Office Gallery until the 31st of July. It will then continue its way to the other cities of Latvia – Rēzekne, Madona and Kandava. The tracing of the “footnotes” goes on and will continue to appear in different forms in the program of the LCCA.

The talks/presentations of the symposium are available for listening here.

Photo reportage from “Revisiting Footnotes I” exhibition at Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art Office Gallery.

Aija Bley Oldcool, 2013