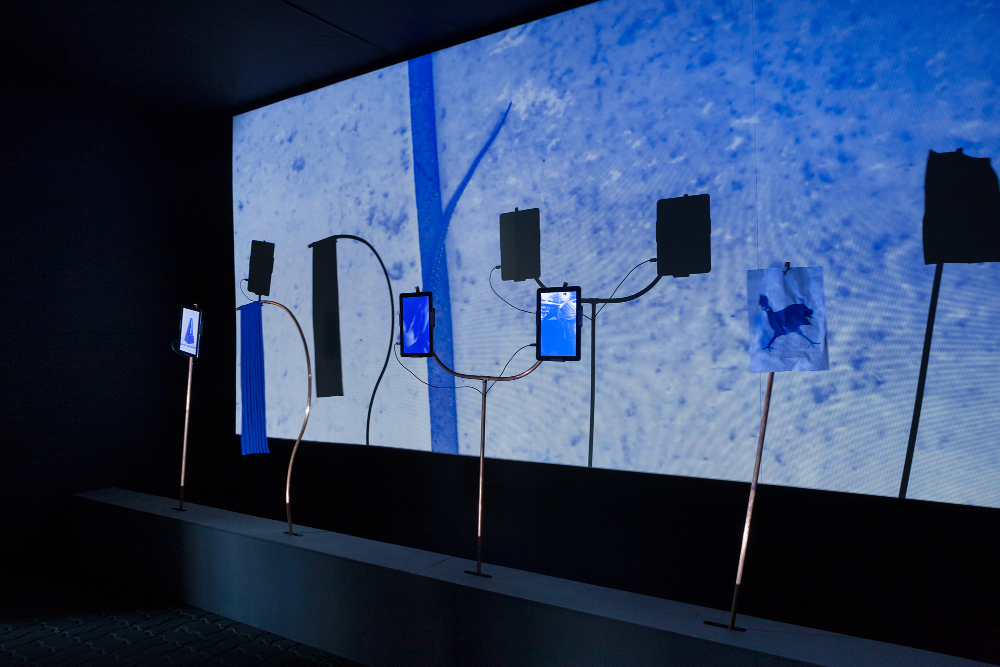

Darja Meļņikova “Room 3. Follow me.” Mixed media installation. 2015

Just as daisy-petal ‘loves me, loves me not’ fortunes are told, our society is engaged in a similar debate regarding the possibility and denial of imminent third World War outbreak. From the Paris terror attacks on the 13th of November last year, or the London bus bombings, to the annexation of Crimea and the ‘refugee crisis’, these have all served as timely reminders that the current idea of Europe as a relatively peaceful and protected zone is utopian, as is mankind’s illusion about eternal peace and harmony. In his famous song ‘Imagine’, John Lennon dreamt of a world with no states, no religions, no heaven nor hell, where everyone would live together in harmony and unity. Unfortunately, let us be honest in saying that our world is only prepared to support this vision of peace if it was delivered as part of some meditative yoga class. Meanwhile, civil unrest carries on, and in all probability will continue to burn through mankind like petrol, possibly even long after the oil reserves have been exhausted.

Reflecting on these events, the Latvian Railway Museum hosted an exhibition with a noteworthy title, ‘A Bigger Peace, A Smaller Peace’ curated by Helēna Demakova who is an art historian, programme manager for ‘Art In Public Space’ (Māksla publiskā telpā) and the former Latvian Minister of Culture. In relation to these events over the past few years, the title of this project might imply a socio-politically themed exhibition, at which point one should note that this was not a festival organised by Solvita Krese, the left-leaning director of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art. Nor was it a politically, economically and geographically tinted project like la grand ‘All the World’s Futures’ curated by the African art-patron Okwui Enwezor, for the 56th Venice Biennale. The exhibition is more like a philosophical contemplation that has been put together in a venue that is always inhabited by old train remains. In a similar manner, the Chilean architect and curator of the 15th International Architecture Exhibition Alejandro Aravena plays with the language of war and unrest in his project ‘REPORTING FROM THE FRONT’, where on a conceptual level the notion of front is transformed into a metaphor for irresponsible construction works. The linguistic and visual communicators of the present moment have now found their way into the arsenal of curators and pose a serious question: has the turmoil that currently tears our world apart and is forcing Europe to dance on thin ice, become an important theme for artists and exhibition organisers, or have these current events simply been transformed into another successful product?

Several art projects touched upon themes of global unrest last year, most often through a historical discourse using collective memory as a reminder or a didactic allusion. One such exhibition called ‘Conflict, Time, Photography’, showing at the Tate Modern between November 2014 and March 2015, reviewed a history of conflict over the last 150 years. Okwui Enwezor took similar approaches in the most grandiose exhibition of his career to date, choosing to show a video work by artist Christian Boltanski from 1969 titled ‘The Coughing Man’, which depicts a man vomiting blood as an allegory of the French national identity. The largely programmatically-driven Golden Lion award at 56th Venice Biennale recently went to the Armenian Pavilion for their exhibition ‘Armenity’, in which several artists from the Armenian Diaspora dedicated their work to commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide. In her herbarium ‘Why Weeds?’ one of the exhibiting artists, Rosana Palazyan, had created an allegory for Armenia — similarly applicable to other persecuted nations, for that matter — made of plants and threads of human hair, posing an imperative question — who gets to decide which plants are good and useful, or those which are harmful weeds?

In comparing ‘A Bigger Peace, A Smaller Peace’ to these exhibitions, the artists’ reflections on internal and external peace seemed reminiscent of a calm and serene island wrapped in cotton wool. Most of the participating artists appeared to be predominantly interested in exploring their own private, inner peace and unrest, or on the contrary, mocked the recent trend to search for inner peace, as was implied in the comic sketch ‘The Happy Prince’ by Andrejs and Ernests Kļaviņš. In this work, the happy prince has become a fully-grown sturdy king who has problems multitasking, in his case between being a monarch and a poet. Led by a coach, this caricature hero journeys further inside his mind. According to the Kļaviņš brothers, the message is simple: ‘The inner world of human beings has little value’ which can be interpreted either as an ironic response to the glorification of materialism, or as a nursery rhyme about the inconsequentiality of intellect used in global decision-making.

Following the escalation of the refugee crisis on a global scale, Russia temporarily ‘left the stage’. For Latvian artists however, Vladimir Putin still remained the only visual symbol of current political events, somehow confirming that the president of Russia is not just an international aggressor, he has become a brand. Photographer Vilnis Vītols took an image of Russia to illustrate the phobias of present-day Latvian people, using manifestations of fiction in the style of Hieronymus Bosch, to create a scary discotheque in an abandoned bunker together with Cheburashka, a ribbon of St George and Putin’s portrait. In contrary to this, the sculptural installation ‘Mushroom Picking in Dresden Forest and Programming of Reality’ by the sculptor Aigars Bikše sees Vladimir Putin transform into a legendary hero — almost a biblical character — in the style of Cindy Sherman, who hears a voice from the other world foretelling Putin the director of the House of Friendship at that time in Dresden, that his new mission is to restore the ruined empire. A few years ago, the national state and its popular symbols used to be high on Kārlis Vītols agenda, who even dedicated his solo exhibition ‘Kults’ (Cult), held at The Mūkusala Art Salon, to this common, yet complex issue at the same time. In a concise manner, his project presented symbols, ornaments, signs and objects, fundamental to the two largest populations in Latvia, which simultaneously confronted each other as opposites — Russians and Latvians. The most impressive work and the main focus of this solo show was undoubtedly a set of light boxes dedicated to the theme of power, arranged in the shape of a classic upside down ‘V’ in the colours of the Latvian flag and St George’s ribbon. And yet, his artwork for ‘A Bigger Peace, A Smaller Peace’ in comparison, appeared lacking in narrative or depth in its storyline, rousing no imagination over its form or elements. There was nothing in his or Kristaps Ģelzis’ work to demonstrate their ability to interpret themes of cult nationalism socially critical or formally interesting ways.

In this exhibition however, the conditions of peace and unrest appeared to have been revealed to us from the viewpoint of a worn out urban dweller, in the manner of Henry David Thoreau. The poetics of the senses and inner mediation, with added contemplation on the different ways of seeing and thinking were crowned with documented fragments of various stories from memory and history. One convincing example of this in the exhibition was Darja Meļņikova’s seemingly ironic altar, which had been created as a form of dedication to the infantile values and modern beliefs of our contemporary society. This example of sacral ecstasy inhabiting today’s popular culture serves as a reminder of the clinical nature of the ‘Law on Decency’ that is currently trending, or the hidden metastasis of new, ‘cleansed’ values and self-censorship, and the lack of empathy towards sexual minorities. At the same time, Kaspars Podnieks’ six photographs of seemingly identical cows successfully demonstrated the workings of our perception mechanisms, reflecting on how societies tend to blindly perceive everyone as being one and the same. Krišs Salmanis’ meditative video work on the importance of our current airspace was also rather compelling. By the early 20th Century the sky had already become a strategic and important war zone, not just in terms of reconnaissance, but also as an arena for the largest weapon of mass destruction, namely the atom bomb. In Salmanis’ characteristic, minimalist style, he turned the sky into a capacious sign through which an Albatross airplane drew a line marking a border between two abstract territories in the sky. Meanwhile, Maija Kurševa accurately portrayed the neurotic nature of our world, visualised as a rumbling theatre of shadows, also featuring sliding images one could be familiar with from a laptop screen.

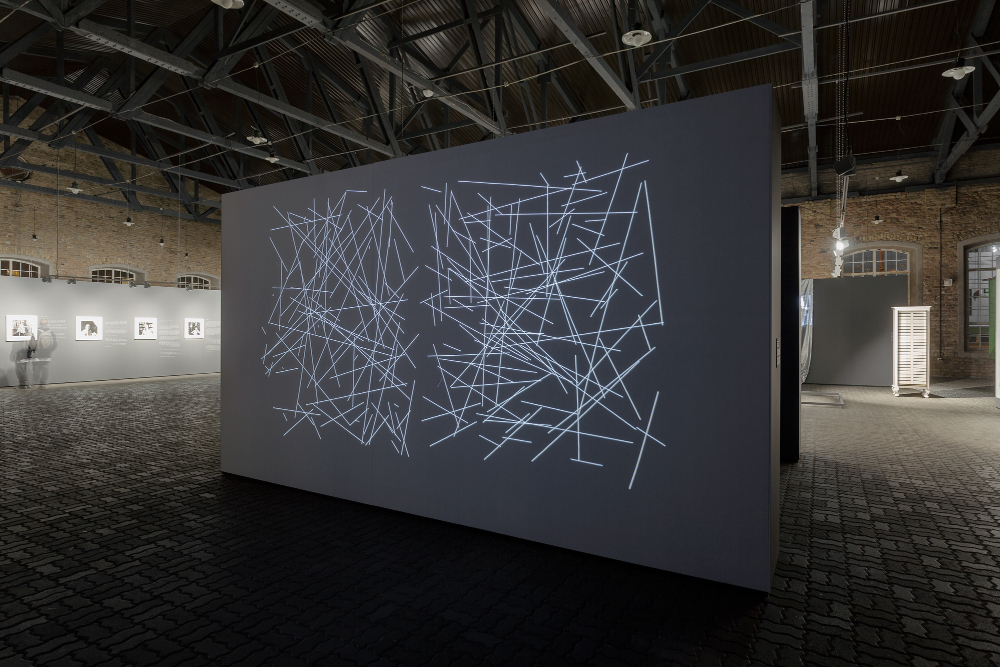

Helēna Demakova’s exhibition ‘A Bigger Peace, A Smaller Peace’ came across as a more substantial curatorial achievement in comparison to her previous exhibition ‘Greetings Head!’ which took place in March 2014 at the same venue. However, her preference towards formalism and simplicity when selecting themes and artists still tends to dominate the Latvian exhibition space. The exhibition ‘Greetings Head!’ seemed feebler as a project, partly due to its awkward title and strange set up that was reminiscent of art fairs held inside small market pavilions. It also seemed weaker due to the fact that her theme had been oversimplified and approached too literally. For this reason, ‘A Bigger Peace, A Smaller Peace’ worked better as an exhibition where new artworks were commissioned. As well, with new commissions, she exposed herself to more curatorial risk, presenting far less predetermined artistic outcomes which can easily run the risk of not looking like a successful exhibition, but which worked out well for her in the end. Whether one likes it or not, Helēna Demakova hybridised her role as a curator for this exhibition, as well as other aforementioned initiatives. On the one hand, in agreeing to develop a concept for an exhibition based on specific issues, she accomplished being able to commission twenty-three artists all representing different generations and directions, whilst striving to materialise her own ideas in an almost artist-like manner. What is more is that she did not intervene in the ensuing process and afforded all her artists’ full creative reign over their works. The interaction between these two curatorial approaches brings about some completely random representations of her chosen theme, yet it is quite obvious the final results are a defined algorithm computed by her as the curator, which is similar to Mārtiņs Ratniks’ video work ‘A Chance Motion’ (2 images: generative animation and digital drawing).

In my opinion, the most significant question this exhibition poses for our current society, which Evita Vasiļjeva’s three ‘X’ signs poignantly illustrate is whether it is possible to find the ideal formula between inner and external peace. The instability of our political and economic situation increases uncertainty and denies us the answers to these questions. Should we be looking deeper inside ourselves just as the Dalai Lama — a Tibetan spiritual leader — urged us to do after the Paris attacks, or is the answer hidden behind the restless nature of human beings? To quote the popular TV show ‘The X Files’: ‘The truth is out there’.

Maija Kurševa “Joviality”. Video, objects. 2015

Kaspars Podnieks “Dze. Prince. Birze. Pienene. Virpa. Palsa. Vel”. Mixed media installation. 2015

Barbara Gaile “Perlglanz Pyrisma Grun”. Acrylic and pigment on canvas. 2015

Evita Vasiļjeva “There Is no Doubt in Singularity”. Mixed media installation. 2015

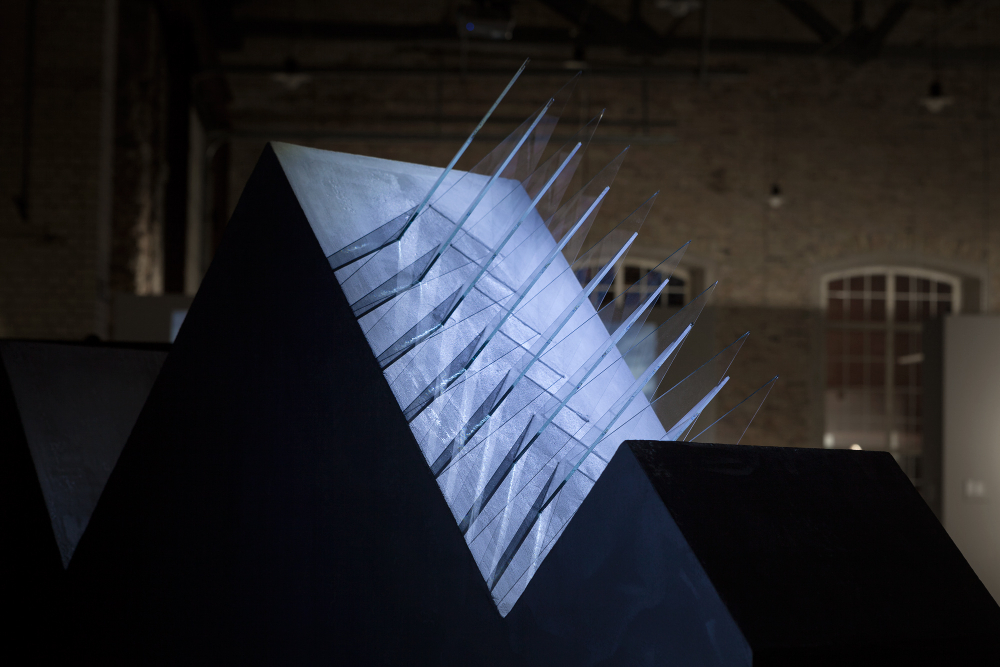

Līga Marcinkeviča “The Situational Vector of What Story Brings You?” Mixed media installation. 2015

Līga Marcinkeviča “The Situational Vector of What Story Brings You?” Mixed media installation. 2015

Darja Meļņikova “Room 3. Follow me.” Mixed media installation. 2015

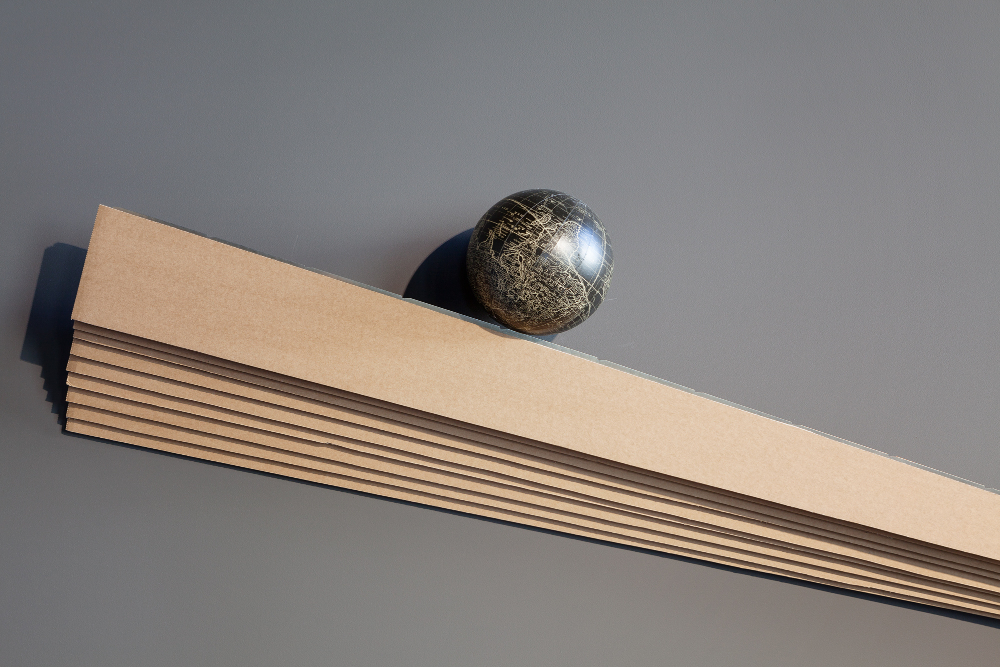

Brigita Zelča-Aispure “The Early Bird Breaks Its Beak Early”. Mixed media installation. 2015

Brigita Zelča-Aispure “The Early Bird Breaks Its Beak Early”. Mixed media installation. 2015

Indriķis Ģelzis (Unitled). Mixed media installation. 2015

Indriķis Ģelzis (Unitled). Mixed media installation. 2015

Ieva Kaula “Subservience”. Clay mass objects, video. 2015

Krista and Reinis Dzudzilo “That Child Caught Sight of Nature and Calmed Down, Nature Caught Sight of the Child and Calmed Down”. Installation. 2015

Krista and Reinis Dzudzilo “That Child Caught Sight of Nature and Calmed Down, Nature Caught Sight of the Child and Calmed Down”. Installation. 2015

Liene Mackus “Foreign Body”. Mixed media installation. 2015

Ieva Rubeze (Without a Title). Video. 2015

Aigars Bikše “Picking Mushrooms in a Dresden Forest and Programming Reality”. Installation. 2015

Krišs Salmanis “Border”. HD video. 2015

“A Bigger Peace, A Smaller Peace”, exhibition view, Latvian Railway Museum. 2015

Inta Ruka. Photography series. 2015

“A Bigger Peace, A Smaller Peace”, exhibition view, Latvian Railway Museum. 2015

“A Bigger Peace, A Smaller Peace”, exhibition view, Latvian Railway Museum. 2015

Mārtiņš Ratniks “Random Movement”, Video. 2015

“A Bigger Peace, A Smaller Peace”, exhibition view, Latvian Railway Museum. 2015

Ieva Rubese “Chacmool as a Book”, without a title, “23 Pairs of Chromosomes”. Mixed media. 2015

“A Bigger Peace, A Smaller Peace”, exhibition view, Latvian Railway Museum. 2015

“A Bigger Peace, A Smaller Peace”, exhibition view, Latvian Railway Museum. 2015

“A Bigger Peace, A Smaller Peace”, exhibition view, Latvian Railway Museum. 2015

Darja Meļņikova “Room 3. Follow me” (detail). Mixed media installation. 2015

Photography by Reinis Hofmanis