What unites all of the works presented at the photography exhibition by Indrė Šerpytytė, a Lithuanian artist living in London? It is a strange feeling to see that everything in the pictures has only a surface, skin, or a shape but lacks content and history – whether it be the depth of the Lithuanian forest that once had been home to partisans (the cycle ”Forest Brothers”), or ordinary village and town houses where they were tortured by the repressive Soviet organs (the cycles “Notebook“ and “Former NKVD-MVD-MGB-KGB Buildings”), or the “clerical”, faceless things that once belonged to the artist’s father who died mysteriously and tragically during the period of Independence ( the series “A State Of Silence”). All of the objects portrayed are like taxidermy specimens, formally indicating a primary object as well as a correlative collective or personal memory but having no vital energy or concreteness whatsoever.

At this point, the essence of the taxidermy art – the act of mounting dead animals – should be remembered. The main goal of a taxidermist is to create a maximally realistic, three-dimensional, tangible image or moulage by means of using the processed skin of a real, concrete animal, stretching the skin over a shape-giving frame and filling it with various materials. It is important that in most cases wild and dangerous animals are mounted – this factor says a lot about the nature of taxidermy itself and also about its interface with Šerpytytė’s work. No less is important the fact that in the epistemological and cognitive sense taxidermy specimens are hollow – they help our gaze to slide only over the surface of a once living organism but basically say nothing about its internal structure and life history. However, by providing a static, tangible body, they enable you to safely touch something which in its live form is rarely accessible to us directly – predatory, untamed nature, non-symbolized traumatic reality.

Taxidermy isn’t an unambiguous phenomenon. It has ties from long ago to both, science (as the stuffed animals of various sizes are common in classic museums of natural history), and the arts (since the taxidermist needs to have a thorough knowledge of the principles of art; besides, larger stuffed animals are specially designed as life-size sculptures, on which real animal skin is slipped on – a number of such animals, next to paintings and sculptures, would embellish luxurious interiors in the Victorian era). One may try to find a common denominator among the taxidermy, science, and art – namely this denominator will help us understand the function Indrė Šerpytytė’s photographs perform.

Both, scientists and artists as well as taxidermists seek to offer the audience a certain abstraction of reality, a model that allows that piece of reality to be observed from different points of view in order to prevent it, figuratively speaking, from biting. Science and art, yet again, just like taxidermy, sublime what is often immense, cumbersome, and hardly accessible in its pure form – nature, reality, the inner world (in both, psychological and physiological, anatomical sense). Thus, one could say that all three reveal and at the same time conceal the things they show. Moreover, the representations given by them include not only some fragments of reality, but also elements that don’t belong to that reality because they are already the products of symbolization, abstractedness – just as an earlier mentioned artificial frame or a sculpture, hidden under the organic fur of a stuffed animal. Therefore, such representations are always the hybrids of multiple worlds and multiple registers of reality that drift in some sort of intermediate space. They cannot be reduced and attributed to any of the worlds. Although the predator’s fur has lost its natural smell, it still mirrors the chill of a forest’s thicket and coolness of a cave, the thrill of hunting and sweat – all that is incognizible for the artificial material underneath it.

The same applies to Indrė Šerpytytė’s model buildings and to the photographs of those buildings, forests, and objects as well. They remind us that the very essence of photography is related to taxidermy as light, which is “hunted down” by the object-glass, is the same flow of photons, illuminating a captured object. A tangible medium, the surface, where this catch of reality is exhibited, however, performs the function of the stuffed animal’s frame. “Something was” before the lens but the image is no longer identical to “something”. However, in this case, that “something” was not as much in front of the lens as in memory and what really stood in front of the lens was only a role-play of memories about it, a diorama, or perhaps even a statement that memories are impossible. These photographs, then, are not so much the taxidermy specimens of reality itself but rather of memory and recollections. In the cycles “A State of Silence” and “Former NKVD-MVD-MGB-KGB Buildings” this impression is further enhanced by an emphatically “museum-like” display mode. Objects and buildings here have lost their concreteness and substance, became a sheer surface which alludes to something painful but does not allow to experience or assure the reliability of memories. Thereby, the images created by Šerpytytė arouse memories and at the same time prevent them from coming too close, freezing them in “a state of silence”, a museum of memory, which in a way reminds us of a natural history museum with hundreds of static but still strangely alive taxidermy specimens, visited by the characters from the “photo-novel” La Jetée by Chris Marker.

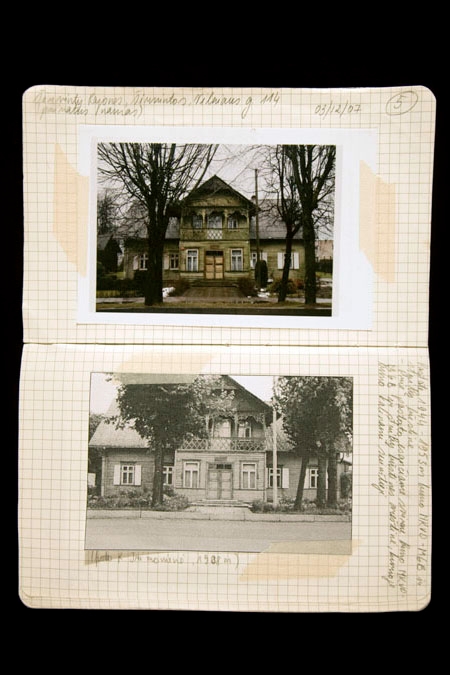

These images enable us “to touch” upon the painful stages of Lithuanian history – the period of occupation and resistance as well as the difficult first decade of independence with its unrevealed crimes and planned deaths. However, the opportunity “to touch“ the concentrated expression of such phenomena causes much controversy. On the one hand, one is secretly happy that the “predator’s” (such as suffering, death) nails, fangs, and the stench from its mouth won’t reach you. On the other – photographic taxidermy specimens astonish you by the triviality and muteness of their objects: for example, former buildings of repressive bodies, symbolically marked with a sign of unimaginable suffering, in many cases visually appear to be uninteresting and undistinguished from other village or town buildings. They are opaque and don’t reveal the dark side of their past, just as the stuffed animals do not reveal “the reality of removed flesh and blood”. Quite the contrary – a stagnant, helpless mounted predator looks harmless and even a little funny. Thus, in order to feel the horrors of a historical period or a mounted animal, taxidermy cannot be trusted: it can only do you an enormous favor. Apparently, this warning about the insecurity of photography, as a means of taxidermy memory, can be read in Šerpytytė’s works. But there is something more.

The recent (post-Soviet and Soviet) archeology, generally speaking, is a common strategy of Lithuanian artists. Sometimes it seems that this topic is inexhaustible to them. The Soviet period and the undisclosed secrets of it are constantly reappearing in a variety of ways – both, through the personal memories and stories of parents or grandparents, or through various archives. How is the Indrė Šerpytytė’s approach different from all these attempts? Many Lithuanian artists (especially those of the middle generation) that tend to look back at the Soviet era find the impulse and basis for their creation in a certain trauma. The creation itself is regarded as a way of dealing with that trauma and sublimating it – unless it was a conscious orientation to a topic still (though much less) in demand in the West. Whereas Šerpytytė, having spent most of her youth outside Lithuania (and therefore, probably, influenced much less by the post-Soviet Lithuanian discourse), apparently, strives for something completely different in her works – to find an answer to the question: “Do I, as a Lithuanian, have this trauma?”. In other words, she tries to find out whether the collective national memory can be meaningfully internalized and become personal. In this case, her photographic specimens of memories act as certain probes, aiming to detect the symptoms of a trauma or their absence.

Šerpytytė Indrė, from the cycle „A State of Silence“, 2007

Šerpytytė Indrė, from the cycle „Former NKVD-MVD-MGB-KGB Buildings“, Gėlių Street, Rūdiškės, 2008

Šerpytytė Indrė, from the cycle „Notebook”, 2007

Jurij Dobriakov is a cultural critic, translator and essayist, publishing critical texts in cultural press and catalogues of art projects.