Artūras Raila, Libretto for Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller. Synopsis, installation detail, National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2016. Photo: Tomas Kapočius

I recently met with artist Artūras Raila to talk about his work from the 1990s within the context of events which changed Lithuania and its entire region. In our conversation we discussed his practice in relation to international art; the dynamics in his work between creator, creation and the viewer; and about “Libretto for Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller. Synopsis” (2012-2015), a new work showed for the first time at the M HKA Museum of Modern Art in Antwerp in May 2015. Its latest version is showing at the National Art Gallery in Vilnius from the 12th of April until the 15th of May 2016.

Neringa Bumblienė: Where did your creative path begin, and what was your first creation?

Artūras Raila: Every artwork I create is my first and my last. For as long as I can remember, I always knew I wanted to work with questions regarding the meaning of existence. It just wasn’t yet clear how I would go about doing so. Quite early on, I understood that I would enjoy working with sculpture which came more easily to me and was comprehensible. I found it to be a form of expression based more on abstract thinking which I could relate to better.

In asking me what my first piece I created is, I don’t know. I could create a myth that, for example, my first artwork was a burning sculpture 80 Slides for Carousel Projector (80 skaidrių karuseliniam projektoriui, 1993), or bikers driving through the Contemporary Art Centre in Once You Pop, You Can’t Stop (Kartą pamėginęs negali sustot, 1997). However, there never truly was a beginning, just as there won’t be an end.

In the 1990s, during the period after the split, what did it mean for you to be creating then when it was clear many things were undergoing changes and, because of this, art would also have to adapt?

I think that I’ve always been in my own place doing exactly what I should have been doing at the time, according to my age and understanding. All of my artworks appeared out of necessity. None of them were commissioned.

Of course, there were very hostile and angry people who have since not disappeared either. Even now, I cannot understand how they can criticise art so bravely without creating anything themselves. I knew many artists from the older generation and I know what I’m saying. As for malicious cultural critics and their absurd illusions, I simply don’t have time for them. Creative people have always been careful with the question of change. They have a feeling that along with the changing times, technologies, intellects, news dynamics and the speed of information, all these inevitably create new needs.

But to return to the moment of the split…

Yes. That simply meant greater opportunities for creative work, easier access to information and more diverse methods. Back then, we met with our peers in England, Germany, Austria and Scandinavia from 1994-1999. Those years were very important as we began communicating with people who had not been affected by socialist ideologies. But now that I think about it, I doubt whether I had personally ever been affected either. I had no obligations to this system or ideology, so you could say that, like my peers in other places, I did not really exist in this. My surroundings in Panevėžys, later in Telšiai, and even partially in Vilnius were somewhat enclosed spaces that the system did not seem to monitor.

It didn’t seem suppressed or closed?

It did, but as something unavoidable, as a part of life.

In the 1990s, the country’s geopolitical, social and economic situations fundamentally changed and other ways to create or simply exist had to be found, as did a new vocabulary to speak about this which did not exist yet. Where did you draw your inspiration from, your references or simply your support, and what influenced you the most?

Questions of vocabulary still remain incredibly relevant for me until this very day. When certain concepts are articulated, they become questions of agreement. Some concepts lose their relevance while others become reactivated. The words are the same, but the questions regarding how they’re used, and what sort of content they model still remain.

Questions of vocabulary were most relevant for institutions at that time, who believed that educating the viewer was very important and, like London galleries and museums, used texts to explain the work displayed. They instructed the viewer as to why it was made in certain ways, or what the collection of works were based on, etc. This did not seem very important to Lithuanian art practitioners, who preferred simply to go out into the wider world and context and reinterpret the language being used for use among their own peers.

When we spoke with you before the opening of your exhibition in Antwerp, you said that one of the most unforgettable films you’d ever seen was Miloš Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975). I thought about that for some time and used that film to search for some sort of key to your work in preparation for this interview.

That’s strange. Perhaps we were discussing something completely different in Antwerp. I remember Forman whenever I think about ordinary forms. Whether it was Amadeus (1984) or One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), at first, it seemed like I was watching a simple costume drama. However, through the plot, the director took me places that forced me to forget form, in which his messages developed. That’s probably what we were discussing. Unfortunately, I can no longer remember.

Okay. In that case, I’ll rephrase my question that in your creative work, you often include people who exist on a sort of fringe, who wouldn’t normally participate within the field of art?

That sounds very strange, as though the “field of art” has a specific list of themes against which it’s possible to define something other as no longer within its field. Let’s just think about that. Gustave Courbet created a large-sized painting of a peasant funeral in 1850, but according to the rules of salon paintings, at that time, it was forbidden to portray commoners on large-format canvases.

I simply don’t see a big difference. Bikers come from various social levels. There are very wealthy people among them who perhaps come first because they can afford to buy a toy like that and participate in club activities – usually these are businessmen. Illegal parties are probably not the only places where one could find people with sympathy for the national socialist ideology who’ll call themselves romantics.

Society is not homogenous or one-dimensional. It is complex and consists of many different interest groups. However, for it to not be part of the field of art or the world of art… Does the field of art really own that list? Who and who doesn’t make it into that list: biker-businessmen; unemployed intellectuals; national-socialist romantics; or people the Catholics call pagans..?

But perhaps that list, which didn’t exist, was an unwritten one? Maybe your art functioned especially because of the inclusion of those people into that unwritten list. Could it be that their very inclusion was the key issue in your work? Perhaps that’s why your artworks became so complex and unexpected as those marginalised social groups were suddenly portrayed in a different light.

Yes, perhaps. By my understanding, these are the processes and energy behind live art, just expressed in new ways. Perhaps Gustave Courbet similarly once touched upon a certain part of society that then became activated within the extent of understanding and knowledge that his times allowed. Maybe the fact that not only specialists, but broader members of society are able to become activated is the essential element behind live art.

Since Courbet’s time, the understanding of modern art has been associated with the need for acute experiences, so we need more and more of them. This is why scandals don’t work anymore. I think that, first of all, live art is active and has the power to affect people, and if society considers this to be scandalous, that’s not art’s problem. Secondly, I think that artistic processes are complex and that true works of art rarely occur.

What is a true work of art?

Unfortunately, a work of art is the result of a legitimisation process. That is how they become real.

While you were speaking, I thought about bikers, mechanics, the unemployed, and their relationship with the spirit of the 1990s. At that time in Lithuania, bikers and the unemployed were a new phenomenon, just like the artistic practices that were used to work with them. After all, in the Soviet times, there were no bikers or unemployed. There couldn’t be any artistic practices like yours, either. In a certain sense, it was a new world for everyone.

That could be. I hadn’t thought about that. I didn’t compare them. I’m no longer interested in how it was back then. The Soviet times are overrated. They receive too much attention. Lithuania is a part of Western culture.

It’s not just a part of Western culture. The historically cyclical and complex political relationship with our Russian neighbour has generally influenced our society and culture as well. In that respect, I believe the 1990s were very important for this region, and many aspects of your work which developed during that time, cannot be separated from important processes which occurred here. I believe that any attempt to separate it would simply be short sighted and strange at the very least, because your works included or tried to include wider segments of society or culture than that of the closed artistic field, that you have mentioned before.

And to discuss it further, what is your relationship, as a creator, with your work and your viewer? I think that, in your work, you often provide an initial impulse, create certain conditions, and then the piece becomes a sort of separate organism that grows on its own.

Yes, that’s something to strive for; an active, living creation. Have you noticed that if the Contemporary Art Centre opens an exhibition, it’s attended by the author’s friends, father, mother, and curator? How do we draw uninterested viewers out of their private spaces? How do we do that?

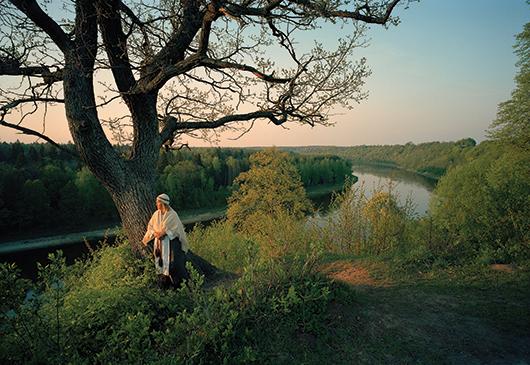

Artūras Raila, River, 2006, chromogenic colour print, 125 × 186cm, from the series Žemės galia (Power of the Earth), 2005—12. Courtesy the artist

Education.

Well, it’s not that simple. I’ve noticed that if a “motor show” is being advertised, and there are posters in the street displaying car engines, people celebrate the fact that the CAC finally has a “normal” show on — that it will display engines and cars. This immediately activates certain societal interest groups that are ready to participate. They are curious and interested.

Power of the Earth: Mythological Vilnius (Žemės galia, CAC, 2008) exhibition was attended by people who were interested in esotericism. Using a map that was on display, one could find their home and room, see where energy lines crossed and formed certain patterns, and they could find out their effects according to psychic explanations. In this case, the motivation seemed personal. I could begin discussing and studying what it was that the artist wished to say, what was it all about? Its dynamic was complex and, without a doubt, has always interested me.

You mentioned how, during the exhibition, car mechanics spoke to journalists saying that they no longer needed the artist and could explain everything to the audience themselves. You created the conditions for this to occur.

Yes. A German TV channel in Berlin heard that sentence from Saulius Stepulis—that they no longer needed the artist to explain things, as participants of the project could do it—with regard to the Roll Over Museum (2005) project in which he was one of the participants. That was a strategic culmination. I consistently worked towards this because, until then, the ravers had implemented a preliminary scenario while the Pompa (Pump for Art – Art for Pump, 1995) observed the situation from afar, and the bikers who drove by took a position twenty metres from the CAC’s audience (Once You Pop, You Can’t Stop 1997). It’s an abyss. That’s when the question arose: How does one regulate the dynamic between a piece and the viewer? The three pillars formulated by Immanuel Kant—materialism, the disinterested viewer and ownership—still apply.

Artūras Raila, It‘s a Great and Difficult Task for an Artist to Dub a Motocycle…Motocycle. 1997, Video installation, National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2016. Photo: Tomas Kapočius

What do you mean by disinterested?

I mean it’s now in the past. The current perceiver is a consumer-participant.

The act of participation.

Yes, or rather, the consequence of the act of participation. They question and model the vocabulary of art. You mentioned Liam Gillick and the artists of his environment and generation. In their hay days, there were only presentiments of all of this. Now, these things are taken as a given, and have permeated all of contemporary culture.

Let’s move on to talking about flying saucers…

I don’t know what that is. I’ve never used that word. I’ve never seen flying plates, nor cups. Here, you’re opening the topic of unnatural phenomena. But perhaps all creative work is an unnatural phenomenon. The entire history of human culture is permeated by strange sights.

My artwork, Primitive Sky (Pirmapradis Dangus, 1980-2002), consisted of five photographs with reconstructed trajectories, five video moments trying to show sights that were seen and the text of a witness. Here, questions of belief, trust and gullibility were discussed — who is one to speak of these things and why should one be trusted? It’s not about plates or cups, and not one single word ever claims that there were objects there. It speaks of points of light that move at a high speed at geometric trajectories. They speed by in the blink of an eye and, it would seem, do not concern themselves with human questions. However, the witness claims the opposite.

Why did the question of belief and trust arise at that moment, specifically, and what influenced that?

The question of belief has been an essential question in our human existence which has been asked in many creative works over the course of time. Sooner or later, most people come to realise this. This involves personal experience, not external influence.

Did you truly see those phenomena?

Yes. I never kept a diary so I could not mark the day. At the time, it seemed so important to me that I’d remember it for my entire life. Later, however, I thought that these sightings might have been birds and that was that… Well, I can assume that now, but earlier, I had no doubt that it couldn’t have been possible in this dimension — such speeds, such trajectories of movement! If you remember, there’s a cluster of dots that move according to strict geometric trajectories, which are very fast and quite sudden. Additionally, their culminating point was recorded — a certain reaction to my thoughts. It was, somewhat, a fantastic assumption that these unknown dots could react to the nature of my thoughts. This [intentionally] de-emphasised moment is the most important one.

Stanislaw Lem’s book Solaris captured my interest only a few years ago. I don’t know if you’ve read it? Andrei Tarkovsky created a film based on this book, but it seemed to me that he had been preoccupied with other things… The book discusses the relationship between the only inhabitant of the planet Solaris, the conscious ocean, and the people researching that planet. It was believed that the visitors appearing in the space station were directly related to people’s thoughts and personal experiences. The plasma of Solaris was realising those ideas. The book also narrates about the pilot, whose experiences nobody believed in…

Science-fiction literature becomes disinteresting because the unknown is often portrayed negatively and from a human’s perspective. This, I believe, is a reflection of the limitations of the human factor. Lem’s book is about the reflection of human negativity, not about the evil of the unknown. However, the majority of fantasy literature, especially film, is the result of the limited imagination.

When you talk, it is as though you are often referring to something that exists beyond us. What is your relationship with faith?

In the past, I have said many times that scientists—with their assumptions and hypotheses—are braver than artists. It seems to me that Marxism and Freudianism, two outlooks born at the end of the 19th century that sought to lay out what they considered to be a materialistic and scientific perspective, have permeated the entire cultural world, and that art has now become a doorkeeper for instrumental rationalism. I believe that it is artists who are the most cowardly and subject to prevailing opinions, despite the fact that their opportunities for artistic creativity are greater than those using these scientific methods. It would seem though, that it’s impossible to do without this entire legacy — without links to brands or bodily relationships. Since 2005, when Raimundas Malašauskas curated BMW exhibition in Vilnius, and Berlin and Paris hosted a thematic exhibition called Melancholy, there have been new desires to remember esotericism, which had once been eliminated: all of the delirium, mysticism and pseudo-science. That’s because they open up the imagination. So now, all of that is hanging in the air, something interesting is happening again within all of this discourse.

The questions of faith and religion are always close to me, and I always explore them respectfully and curiously. The meeting platform formed in Power of the Earth: Mythological Vilnius was activated very intensely and was used as a way to see old, well-known things from new perspectives. The same is the case with Libretto for Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller. Synopsis. A beam of light cuts through the photo’s image, and though one knows that this is an effect caused by the camera being held incorrectly, one can read its message according to examples from classical art that help construct a codified frame to tell its story. However, both of these works are radical opposites.

I have to say I don’t put much meaning into the methods of artistic expression and that I do not value Libretto for Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller. Synopsis through the format of animation, or that the content defines the techniques used. The result of one thousand five hundred drawings became one minute and twenty seconds. From a professional animator’s perspective, this is nothing. They draw tens of thousands of them all the time. But this took me half a year, and I got tired of it. It became laborious and physically difficult. Sometimes, I couldn’t create a single second, which required 25 drawings, in a day. However, that was the idea. The technique chosen became an inherent part of the work.

Speaking of balance, compared to the project Power of the Earth: Mythological Vilnius (2005-2012), my creative method for this piece became a radical turn in the opposite direction. Here, I remained totally alone, and the main tool for my work was a pencil.

Artūras Raila, Libretto for Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller. Synopsis, installation detail, National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2016. Photo: Tomas Kapočius

Artūras Raila, Libretto for Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller. Synopsis, installation detail, National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2016. Photo: Tomas Kapočius

Libretto for Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller. Synopsis is also very different from your other pieces because, before, you’d given a certain impulse for the artwork to develop later on its own, separate from you. This libretto, however, was written and drawn by you and, in that sense, had a clear frame.

Yes and no. Libretto for Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller. Synopsis indicates an interim state. Does anyone care about who in the opera the author of the libretto is? This proposal, however, can potentially be continued by other authors in other formats.

Yes, but that’s not what I’m talking about specifically. This artwork consists of animated films drawn by you, although unlike your other works, in Libretto for Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller. Synopsis, you are speaking.

No. It’s not me speaking.

Then who?

An intermediary. You must read more carefully, look closer. It describes the circumstances surrounding an otherworldly message. The piece speaks in quotes: there are several sentences from human rights, one from a speech by Putin, a statement by Pope Francis. You won’t find me anywhere at all. That’s why the protagonist, Cutout, is totally inactive, he’s an intermediary. There is no author.

It’s a libretto because it’s an open text that can be expanded to become a piece for the stage.

However, you offered the first animated version of the libretto.

That’s how it formed itself. Again, if you read the beginning, it says that Cutout is trying to avoid what has to be done, but then the circumstances of life are still forced upon him.

Could you expand on this?

I wrote the first sentences of the libretto in 2012. Only later, in 2013, did I add a bit to it because of the text’s density and continuity. The essence, however, did not change. The synopsis remained as such.

Later, I rewrote the sentences in pencil and drew the figures for the characters. Then, I realised that I wanted to see what the characters were doing because I didn’t know the dynamics of their actions. This is how they came to life a second by second. It was a very slow process. The eight scenes were constructed as a line of horizon so that all of the characters and events could be seen immediately.

Would you plan on creating an opera?

A.R.: I understand that the libretto could be activated in this way, but that would be another artwork entirely.

Thank you for the conversation!