Nasreddine Bennacer and Krishna Reddy, Paper Trampoline, 2018. Photo: Otto Strazds, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

three pastels on Japanese paper, stretched on metal ring; diameters: 370 cm, 240 cm, 180 cm

The tenth Survival Kit contemporary art festival (the first part runs from 6 to 30 September 2018, the second part will be in May 2019) is focused on the concept of ‘outlands’, which the curators define as ‘questioning the traditional geopolitical and cultural division between the centre and the periphery’. Of course, the term can be understood both literally and metaphorically, and the latter is flexible enough to be applied in a broader context, and thus includes identity-related issues and the marginalisation of the Other. Consequently, the term opens up a Pandora’s Box, offering a journey into conceptual dilemmas, both epistemological and discourse-related, which are so characteristic of contemporary art, and to a certain degree demand that the audience be well or perfectly informed before they approach the artwork.

Since Survival Kit 10 offers a range of works, with their authors coming from countries as distant as India, Brazil, Sudan and Algeria (or being nomadic globetrotters), in this case, at least, audiences should be aware of the discussions of the Other in anthropology and the postcolonial discourse. These discussions include sensitive issues of terminology: for example, is it appropriate to use terms such as ‘exotic’, ‘unique’ or ‘authentic’ when arguing about value hierarchies across cultures? The plurality of meanings that can be applied to address the term ‘culture’ is already an indicator of the difficulties we have to face; and, as a result, a series of rhetorical questions emerge. In this respect, Survival Kit 10 demands an active relationship model between the work and the audience, where each spectator becomes actively engaged, both in terms of cognitive and sensory apparatus. I see it as a beautiful deviation from the comfortable modes of cultural consumption and polished gallery spaces. There is also a strong educational focus: to teach audiences how to appreciate ‘different’ type of aesthetics, and how to expand hypothetically constructed boundaries when we think about art, its definition and its meanings.

Slavs and Tatars, Exposition view, 2018. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

Agnieszka Polska, Medical Gymnastics, 2008. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

HD video; length 8′ 3″

One of the most important structural elements in Survival Kit 10 is its location. The choice was based on some of the founding principles of Survival Kit and its genealogy. The first Survival Kit was held in 2008, when the global economic crisis struck everywhere, including in Latvia. In response to the empty streets and shops, and abandoned buildings and public spaces, artists were offered the chance to fill the spaces again with all kinds of initiatives: poetry readings, pop-up shops, soup kitchens, etc. The quest for abandoned and forgotten buildings has become a tradition, and this year the curators decided to take over the empty and historical building of Riga Circus.

The story of Riga Circus is both intriguing and sad. As a building, it is one of the oldest circus buildings in Europe: it was founded in 1888. It is also unique, since it is the only self-sustained circus building in the Baltic States, which means that the whole circus, including the animals that were exploited in its performances, lived under one roof (unlike travelling circuses). This precondition required that the architecture of the building was adapted to the needs of its inhabitants. Therefore, we can find a diversity of spaces designed for different purposes; for example, there are rooms to keep the reptiles, predatory animals, and even large mammals such as elephants (five in one room!). The walls are painted in a mixture of dirty brown and dirty yellow paint, and they are, of course, in a dilapidated state. We can only imagine the suffering and the tragic fates of the animals that had to spend their days in these conditions. Ironically, the English idiom ‘an elephant in the room’, as a metaphor for discussing a controversial issue that everyone is aware of but deliberately ignores, seems to be the right definition for this situation.

The glory of the performances and the carnivalesque, joyful atmosphere associated with the circus arena, at least in the imagination of Soviet audiences, is in stark contrast with the scene backstage. It really turns the entire circus institution into a grotesque artefact full of once such heart-warming children’s laughter, and camouflaged animal suffering, with physical punishment being the standard training method. Thus, the location opens up as a multi-layered structure with different meanings, where not only is the act of looking needed, but other senses participate too. Circus becomes an olfactory medium, where the smells (of mould, of previous inhabitants, of a decaying building) attack the sensory apparatus of audiences. It also makes us realise how ocular-centric (Western) visual culture is, and how we take vision for granted when it comes to interpreting visual content.

Nasreddine Bennacer and Krishna Reddy, Paper Trampoline, 2018. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

three pastels on Japanese paper, stretched on metal ring; diameters: 370 cm, 240 cm, 180 cm

Performance by Orbita, 2018. Photo: Ģirts Raģelis, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

In this context, the curatorial choices for the exhibition Survival Kit 10 should be viewed from a broader perspective. It is not only the artwork that fills the premises, but also the building itself, which adds another semantic and sensory layer, and stipulates that not only do we look at the objects presented to us, but we experience them. This requires that we use a more all-encompassing term to refer to it, such as ‘a project’ or ‘total artwork’. Here, the collective efforts of artists and curators are subjected to the location, turning the entire exhibition into site-specific artwork. This integrative approach resonates with historical precedents of artistic synthesis, when, for example, Richard Wagner suggested Gesamtkuntswerk, or Antonin Artaud proposed artwork that would address all our senses, and which would ‘[wake] us up: nerves and heart’ (Artaud 1958 [1933]: 84).

Cassius Fadlabi, Tirailleurs Senegalais, 2018. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

acrylic paint, mural; 300×670 cm

Performance by Cibelle Cavalli Bastos, Sonja Khalecallon’s Products for a Better Life, Their Story News from the Retrofuture.2018. Photo: Ģirts Raģelis, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

Given the spacious location, the number of artists whose artwork is exhibited in Survival Kit 10 is relatively small: there are ‘only’ 13, and one artists’ collective (Orbita). This can be explained by the curatorial decision to split the event into two parts, where the second part will follow in May 2019. It is impossible to examine all of them in detail, but I would like to mention some of them. The first work that audiences encounter is actually situated outside the building, and is painted on one of the walls in the backyard of the circus. It is a mural depicting the famous Laika, the first dog in space, flanked by two Ethiopian angels. The artist is Cassius Fadlabi, a Sudanese artist, who lives and works in Oslo. In the mural, and in his work overall, Fadlabi refers to postcolonial theory, reflecting on the history of exploitation when it comes to people of colour. The title of the mural is Tirailleurs Senegalais, which is French for Senegalese sharpshooters, a sarcastic name given to Senegalese soldiers by the French during the First World War. Since the Senegalese soldiers were not properly trained, they were terrible shooters, and were often brutally sent to the front line to test the capacity of the enemy, resulting in their immediate death.

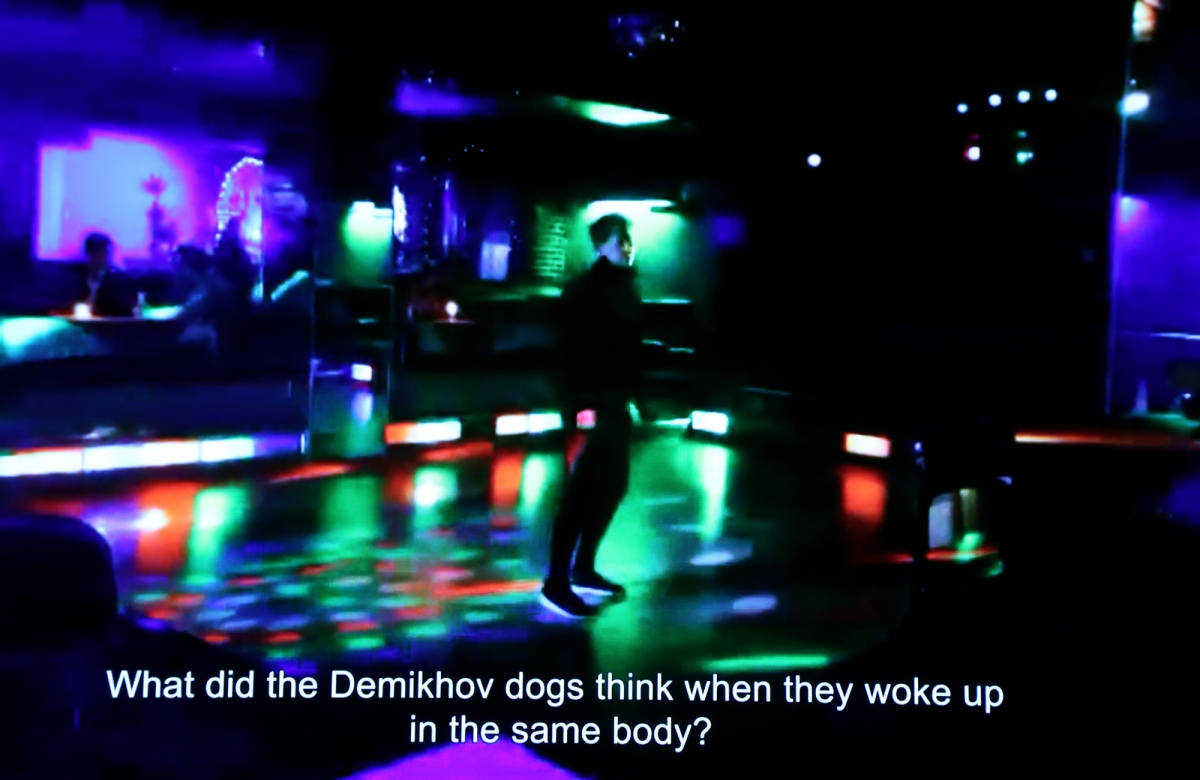

The figure of a dog reappears in the work of other artists, too. One is the work Demikhov Dog (2017) by the Russian-Lithuanian artist Anastasia Sosunova, who based her video installation on the experiments by the Russian scientist Vladimir Demikhov. He was known for his tests on animals, aiming at creating one organism by sowing together body parts from different specimens (his two-headed dog is, in fact, exhibited in the Anatomy Museum of Riga). Sosunova uses the reference to Demikhov as a metaphor for her own struggles with a hybrid identity, growing up in a Russian family on the periphery of Lithuania. Another work referencing dogs is the work by the Estonian artist Kris Lemsalu Phantom Camp (2012), which is an installation consisting of several objects, anthropomorphised dogs in sleeping bags. Within the framework of hierarchical power structures that Survival Kit 10 addresses, the metaphor seems very eloquent: migrants, homeless people, and all those who are not accepted by most of society as some kind of deviation from the norm, are subjected to existential and degrading survival on the outskirts. It is significant that the figures of dogs have their eyes closed, a reference to the pretentiousness of a society that chooses to ignore and not to see, or the protective mechanisms of the victims themselves.

Anastasia Sosunova, Demikhov Dog, 2017. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

video installation; length 7′ 18″

Anastasia Sosunova, Demikhov Dog, 2017. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

video installation; length 7′ 18″

Kris Lemsalu, Phantom Camp, 2012. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

ceramics, sleeping bags; dimensions variable

Outlands as a concept for identity-related issues is tackled by the Polish artist Janek Simon, who has had projects in Madagascar, southern India and Africa. In Riga, Simon offers his work Adventures of Mr. Seven (2013), which is an installation combining video and a collection of found objects. The video shows an interview with an Indian man in his 60s, who is sharing the hard-to-believe adventures of his life with a deadpan facial expression. Reminiscent of Baron Munchausen, Mr Seven could also be interpreted as Simon’s alter ego with a fluid identity. Another work that addresses the question of identity is the installation/environment Las Venus Resort Hotel: Chill Out Dimensional Fold (2018) by the Brazilian artist Cibelle Cavalli Bastos. The artist defies the binary categorisation of gender, and insists on being referred to as ‘they’. Something as simple as a choice of pronoun that we tend to take for granted actually signifies complex processes of deconstruction and formation of identity, where language is a system that we use for the construction of identity. The conceptual work created for Survival Kit 10 is another instance of a polysemantic palimpsest, where tacky camp aesthetics imbue the work with a certain ambivalence: the carnival is over, and the harsh reality remains. The work challenges notions such as beauty, value and taste, representing the opposite of ‘high art’.

Janek Simon. Adventures of Mister Seven, 2013. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

single-channel HD video and collection of found objects; dimensions variable, length 88′ 13″

Overall, Survival Kit 10 arouses the feeling of in-between, of liminality and a threshold state, of being neither here nor there. As an instance of total art, where the building of Riga Circus plays a crucial role as an integral element of the site-specific exhibition project, Survival Kit 10 deals with a range of questions contained in the rich concept of ‘outlands’: hybrid identity issues, ethical questions, abusive power hierarchies, and knowledge creation processes.

Reference: Artaud, Antonin. (1958 [1933]). The Theatre and Its Double. New York: Grove Press

Kader Attia. Reflecting Memory, 2016. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

HD video, 48′, installation in collaboration with Vladimirs Jakušonoks; installation dimensions variable.

Kader Attia. Reflecting Memory, 2016. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

HD video, 48′, installation in collaboration with Vladimirs Jakušonoks; installation dimensions variable.

Performance by Katrina Neiburga, DJ Selecta un VJ Nei, Ragnagmati, 2018. Photo: Otto Strazds, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

Roman Korovin, Car for sale, 2018. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

photographs, paintings; installation dimensions variable, 2 photographs: 150×150 cm

Roman Korovin, Car for sale, 2018. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

photographs, paintings; installation dimensions variable, 2 photographs: 150×150 cm

Roman Korovin, Car for sale, 2018. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

photographs, paintings; installation dimensions variable, 2 photographs: 150×150 cm

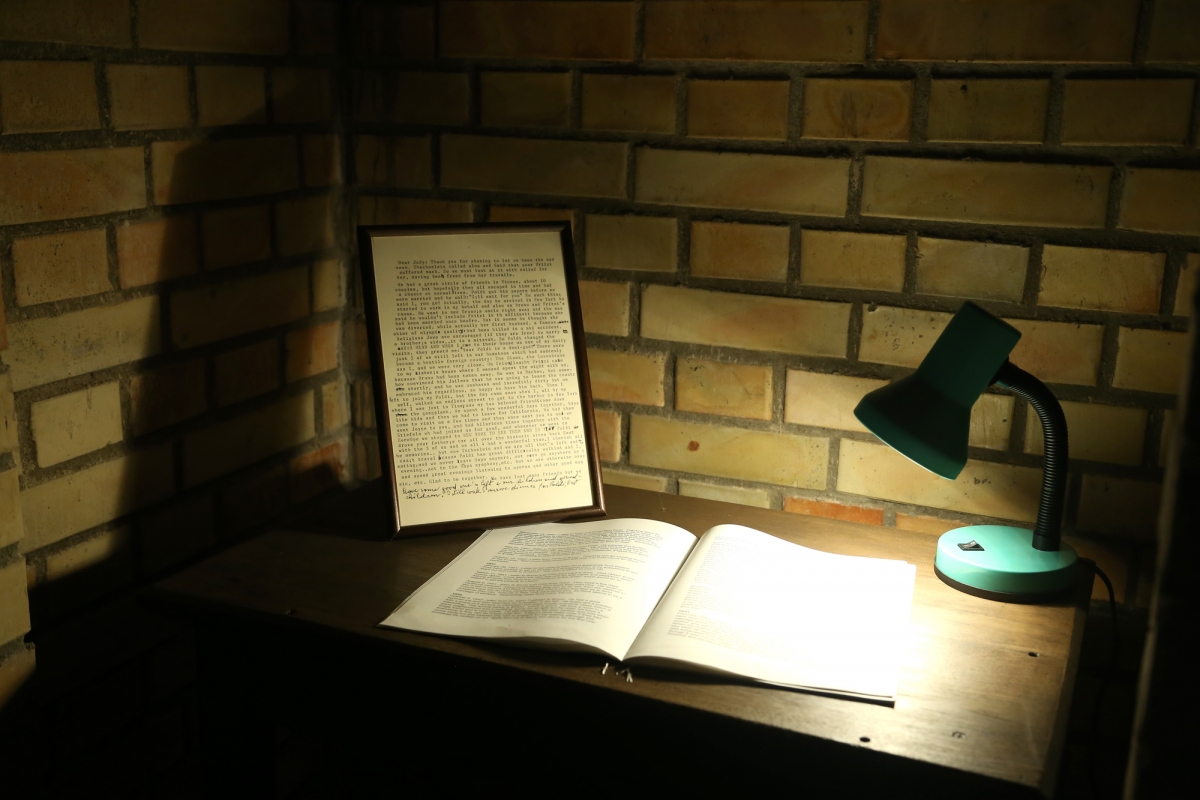

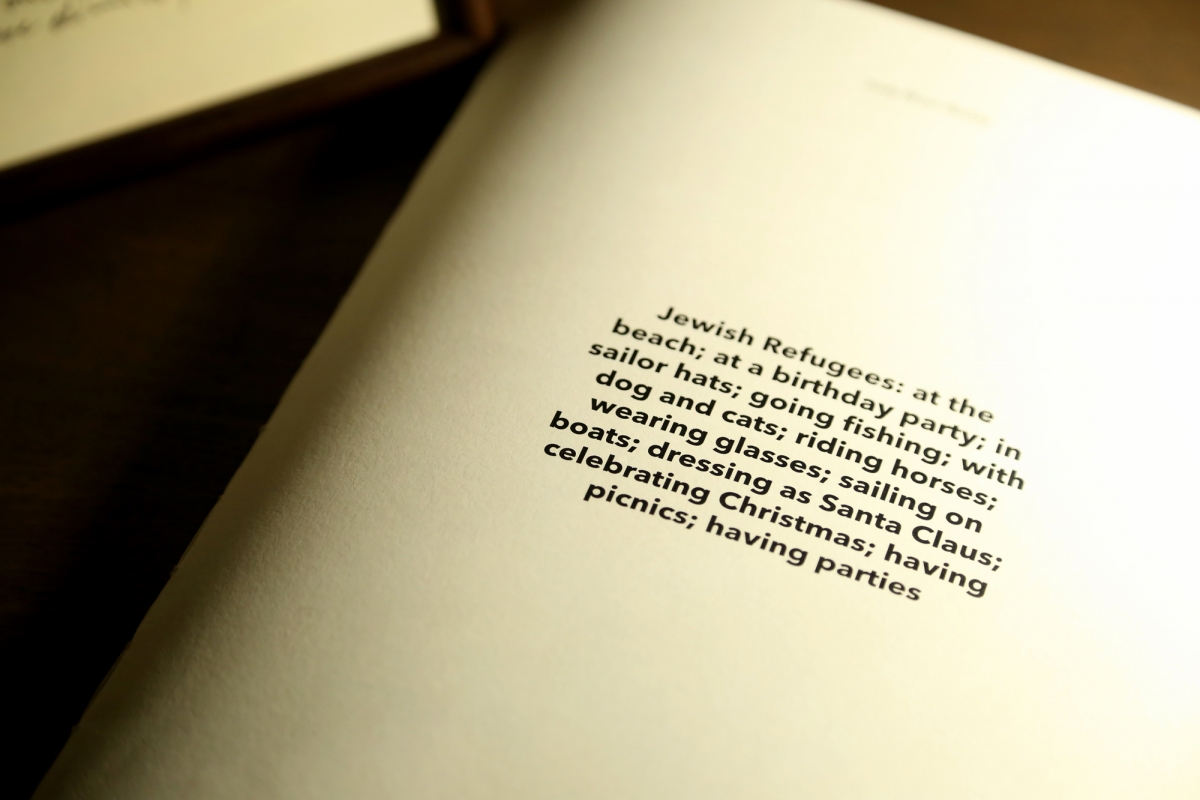

Judy Blum Reddy, Jewish Refugees: at the beach; at a birthday party; in sailor hats; going fishing; with dog and cats; riding horses; wearing glasses; sailing on boats; dressing as Santa Claus; celebrating Christmas; having picnics; having parties, 2017. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

restored 16 mm film, HD video, letters; length 130′

Judy Blum Reddy, Jewish Refugees: at the beach; at a birthday party; in sailor hats; going fishing; with dog and cats; riding horses; wearing glasses; sailing on boats; dressing as Santa Claus; celebrating Christmas; having picnics; having parties, 2017. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

restored 16 mm film, HD video, letters; length 130′

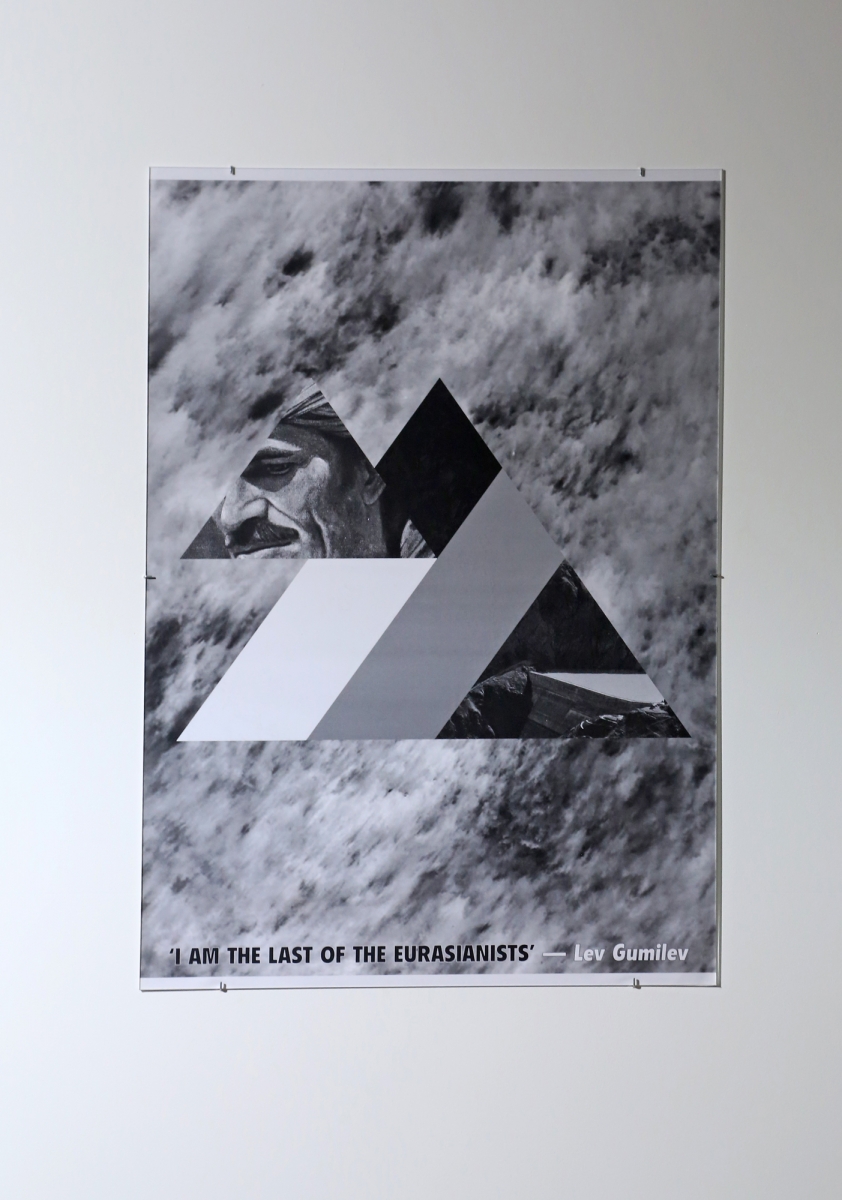

Slavs and Tatars, Kidnapping Mountains (Over-Here), 2009. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

screenprint on paper; 176×120 cm

Zīle Ziemele. Exposition view, 2018. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

Kris Lemsalu, Phantom Camp, 2012. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

ceramics, sleeping bags; dimensions variable

Kris Lemsalu, Phantom Camp, 2012. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

ceramics, sleeping bags; dimensions variable