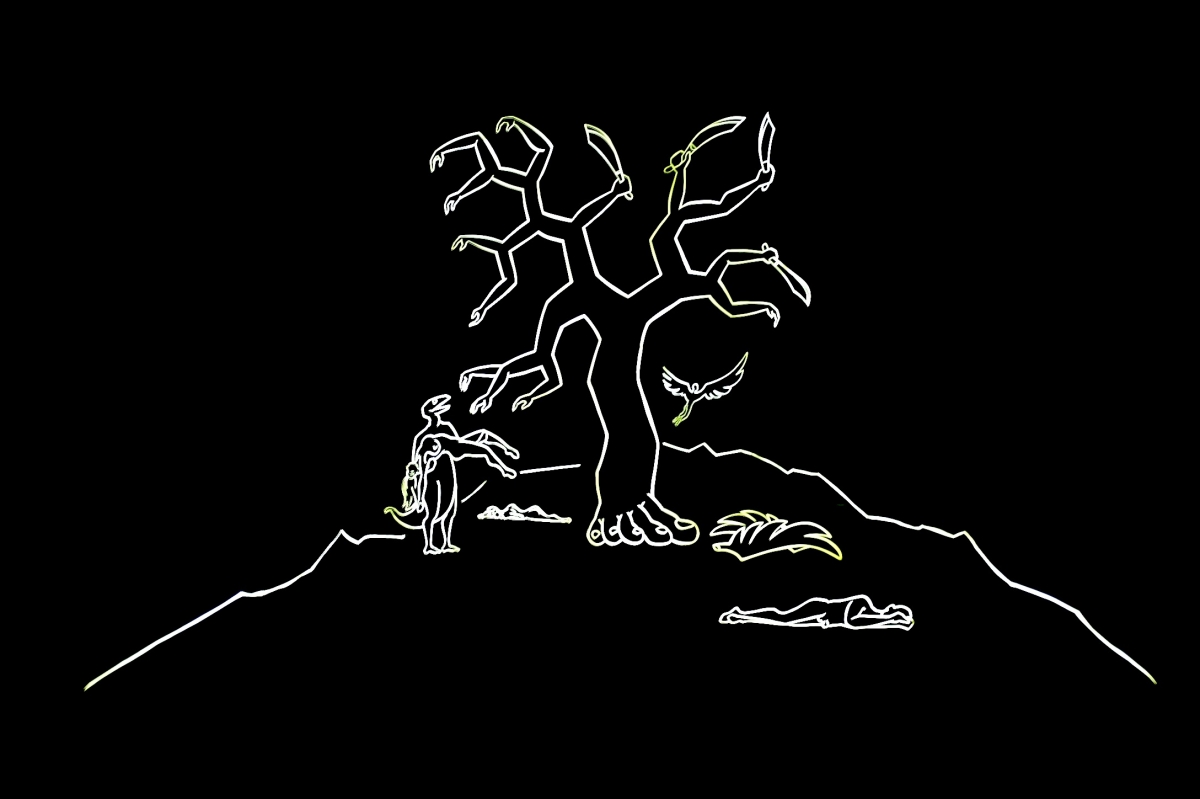

Miķelis Fišers, What Can Go Wrong, Latvian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. Photo: Mārtiņš Grauds

This year, 13 May marks the opening of the 57th Venice Biennale, at which Latvia was represented by Miķelis Fišers, with his solo exhibition What Can Go Wrong. Inga Šteimane, the curator of the Latvian exhibition, believes that Fišers’ esoteric deviations are interesting, and also possibly the only unbiased way at this moment to touch on some of the global socio-political issues worrying people around the world. And the apocalyptic themes he engages so intensely and playfully in his artwork lead to thoughts about Hannah Arendt’s concept of the ‘banality of evil’. We recently spoke with Fišers and Šteimane about the biennale, including this year’s theme ‘Viva Arte Viva’. Does this theme, chosen by the festival’s director Christine Macel, allow artists to shut themselves away in escapism, or does it encourage them to use the act of creativity to stand their ground in the face of difficulties?

Laura Brokāne: Can you tell us how you reached the final version of the Latvian exhibition?

Miķelis Fišers: The exhibition consists of three parts: 16 woodcarvings in the hall of columns, a large-format hexagonal painting, and monumental light installations in a long, triangular space with sound by Error, similar to the installation Mountain Climber at the Cēsis Art Festival a year ago. After long discussions, we received an additional space that until then was unused. The space has no floor, so you cannot enter it; you can only look in through the window. With it, however, we almost doubled the space available to the Latvian exhibition at the Venice Biennale, and found the necessary room for a light-and-sound installation.

Inga Šteimane: The exhibition is based on quite a classic trilogy format. One segment is the small woodcarvings from Miķelis’ solo exhibition Unfairness. Then, by looking for a related but monumental technique, we arrived at the light installation. And the third segment is the large-format painting.

MF: I am, of course, continuing the themes in Unfairness: conspiracy theories.

IŠ: Dramatically speaking, these small carved boards are dystopian. They contain all sorts of ugliness.

MF: Irony, which sometimes borders on cynicism, and various types of criticism: all of this can be seen in the carved boards and the light installation, which is like an enlargement of the boards. For balance, I had hoped to make a dolefully enthusiastic painting that would tell about the development of the universe from entropy and chaos to higher forms of life. That was very bold of me, bordering on foolishness. I had imagined painting an epochal work on commission, within a certain amount of time. And that doesn’t mean standing in my workshop, painting whatever I want, and if it doesn’t work out, starting the next painting. But I found myself in a predicament, because while I was painting, I realised that my personal experience was not in the work. I had figured out what the movement would be like, that everything would be beautiful, and everyone would like it. But then, at one point, I understood that it wasn’t for real. I needed to create something that would stand opposite the ideas in the little boards.

And then I went through everything, listened to lectures, contemplated, read, and understood that it was my own ego that was preventing me from creating this idea. The painting finally emerged after being washed off several times, and it’s about struggle and emancipation from the ego. Its title is Breakthrough. Farewell to Selfness. Selfness, however, is not a precise word: it doesn’t refer to existence, but rather to the ego. Of course, I don’t want to claim that I’ve emancipated myself from my ego, but at least I’ve begun to look at the issue seriously. Actually, I didn’t really paint the painting; instead, the painting transformed me. Even my method of meditating changed. I noticed that as soon as I began thinking about how I and the Latvian exhibition would be received, nothing worked any more. But when I painted what I was really thinking, then it worked. It was an unending struggle. The insanity is in the obligation, and in the fact that I had to paint, if not the best work of my life, then at least a very good piece.

And … well, the result is something that is at once repulsive and beautiful. By no means do I want to impose my own interpretation, but one could say that the painting consists of three parts: the world of the ego, which is pretty flat and simple (the screaming ego will do anything to maintain its position and dominate); the things that hide behind this reality, behind the visible world (similar to the way in which a beautiful body hides the innards that allow it to function); and the bottom part is ambiguous and multi-layered, it is the not-fully-defined, not-fully-developed, true existence, in which everything is possible. But that’s just my version of it. I was more like just the executor. The less I control, the better it comes out.

Miķelis Fišers and Inga Šteimane at , Latvian Pavilion, 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. Photo: Mārtiņš Grauds

LB: This process of creative torture coincides with the theme of this year’s Venice Biennale, which can be interpreted as an artist’s independence, as opposed to, for example, socio-political involvement.

IŠ: In our conversations with Miķelis we came to the conclusion that his esoteric deviations and fluctuations could at this period be one of the rare unbiased ways of highlighting socio-political issues; and a way of presenting these idealistic visions in such a way that the somersault-like intensity of his work might let viewers begin to think seriously about socially important issues. Other methods can really make the issues seem flat and ‘made to order’.

LB: It is precisely the imagination that is important when trying to comprehend and empathise.

IŠ: Yes, Miķelis works with old values, images. An image is actually a completely esoteric thing, because it is an assumed view that has formed over the long existence of art, which the professionals know and which no one else can either record or repeat; everyone has to begin at zero. Miķelis works with this kind of understanding of art. But at the same time, he also has a conceptual frame, which manifests itself in his added stylisations. That seemed very interesting to me. And it stands opposite the bias of contemporary art, which in terms of form must not resemble a classic work of art, or work with the image, but which instead resembles something more like a consumer object or a non-material, assumed substance.

In contemplating how artists have come into contact with the occult, the supernatural, the paranormal, we also came across a link with classic modernism. For a long time no one talked about the theosophical ideas of [Vassily] Kandinsky and the other Expressionists. They often based their radical, formal transformations on deeper visions. Interestingly, Miķelis uses the same theosophical resources that were available to Kandinsky: Helena Blavatsky, Nicholas Roerich, Rudolf Steiner. One can track how completely different works of art are created from the same foundation. This foundation led Kandinsky to abstraction, but it leads Miķelis to ‘literature’, as he says himself. This motif that something needs to change, that this is the last straw, can be found a hundred years ago, and also in Miķelis’ rhetoric today.

In order for the exhibition to be richer in context, I have sketched out in the biennale’s catalogue some of the possible esoteric narratives that are also found in the work of some other Latvian artists, including Diāna Adamaite’s quest for an alternative ethos, Arturs Virtmanis’ occult overtones, and Gints Gabrāns’ themes of enhanced consciousness. Thus, Miķelis is placed in a small group of his countrymen.

Miķelis Fišers, What Can Go Wrong, Latvian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. Photo: Mārtiņš Grauds

LB: Inga, it is very important for you that Miķelis should not be misunderstood in Venice. Is it a misunderstanding to attribute reflections about today’s post-truth situation to his art?

IŠ: Roland Barthes explained that, to put it simply, myth is created by erasing history from a specific fact. In terms of presentation, that means erasing verbs, when only proof remains that something exists. In his invented myths, which contain fictitious facts, Miķelis achieves the effect of history through form, through the title, which contains a verb, and through detail. This is especially the case with his woodcarvings. With a precise description of place and attitudes. It’s a strange process, in which the viewer is led into an unusual form of history. One can contemplate whether that could be defined as post-truth, or rather as metaphors that point to truths.

LB: When you imagine, you return…

IŠ: To the fact, or, let’s call it truth. I categorically reject the interpretation that Miķelis is only goofing off with his art. If that were the case, he wouldn’t have the purposefulness with which these actions and plots are developed.

MF: Maybe he’s goofing off with tears in his eyes (laughs).

IŠ: Well, of course, an artist’s world is at least ambivalent and incomprehensible.

LB: When speaking about the forthcoming exhibition, Inga, you used Hannah Arendt’s concept of the banality of evil.

IŠ: Yes, Arendt says that evil is nothing extraordinary. What is extraordinary and worthy of cultivation is goodness: humanism. And evil can emerge quite naturally, which is why it is banal. I think that’s beautifully formulated idealism, which likens evil with banality, and puts forth humanism as something worthy of cultivation. I think this exhibition could be an investment in turning our thoughts to this theme.

LB: And so we come to the theme of an artist’s responsibility.

IŠ: Miķelis knows how to formulate this, he always reminds us of the responsibility of the artist. Although it’s complicated for him …

MF: It is complicated. And I don’t want to moralise in a textual format, considering that I already do that indirectly in my work.

LB: Tell us about the title of the work, What Can Go Wrong.

MF: It can be understood as a question. And in the small boards, you can see the bad things that can happen. But it can also be a declaration, the quality of being sceptical, or something else, whatever the viewer wants. From a cosmic point of view, of course, nothing bad can happen. Even if our lives are destructive and we’re destroying the planet, why assume that’s bad? Maybe we need to acquire this experience at the landfill; maybe there’s no other way for our souls to learn anything. Humanity isn’t something so very wonderful that we should get extremely worried about it, from the cosmic point of view, of course. So, I don’t think the title is pessimistic at all.

IŠ: I think the title has succeeded in realising that special formula that’s so characteristic of Miķelis: he’s able to create slogans that automatically contain duality. Ever since his very early work. Of course, we expect art to be so miraculously significant, so full of many different meanings. This title alone creates a space in which thoughts can go round 360 degrees, and spherically, too; and wherever they stop, there will be a context, whether it’s purely a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’, or something else; but that won’t be the only context. And I like that.

LB: The title is also a powerful image.

IŠ: Yes. It contains a philosophical question, but it is also simply clever. In general, I like the way Miķelis works with language in his art. I believe the form and content have turned out well. It’s characteristic of his work that the content contains both a ‘yes’ and a ‘no’ at the same time: it’s not lyrical esotericism in which you can comfort yourself; instead, you try to grasp the ungraspable.

LB: With regard to the theme of this year’s biennale, can it be interpreted as escapism and shutting oneself away in the mind of a genius?

IŠ: It could be. People are already smouldering about the need to search for new borders in art. The convergence of art with everyday objects has been happening for some time already, and there’s really no direction left in which to continue this, so there’s a desire to stake out new borders. The concept of ‘art’ is at the centre of the biennale’s theme, but it hasn’t really been explained; they’ve only relied on a powerful tradition. Intuition and the artist’s special world are stressed, as is allowing the artist to exist in this special world, of course. The question is, how to harness the artist’s escapism, without losing the connection with everything else. Very simply put, the answer is that, by existing in a unified space, art is probably not able to shut itself off from the rest of the world.

LB: How would you, in general, describe the preparation process for the biennale?

MF: I think it would be much cleverer and more rational to have artists submit already-existing works of art for exhibition at the biennale, because the stress of preparing new work for it sometimes seems intolerable. Obligation is so difficult to combine with creativity … Then again, perhaps without that suffering, there might not have been a result. Everything’s probably all right the way it is, but I would have liked the process to be calmer (laughs).

IŠ: Yes, I also felt a great responsibility as a curator. The usual way of interpreting an artist is to put your knowledge on the table, understand the type of space you’re working with, and then position the work of art. But in thinking about Miķelis in the context of the biennale, I understood that it’s difficult to get an overview. The space is very large, and doubts creep in about what others know or do not know.

LB: And the already-mentioned anxiety about being misunderstood.

IŠ: Exactly. Even if you don’t worry much about being misunderstood, you still have this responsibility, which should definitely be said. Even if each viewer, no matter whether a simple visitor or a professional, finds something of his or her own in the work of art, and adds his or her own remark, I still need to know exactly what I should say. When working with the Latvian exhibition at the Venice Biennale, one encounters plurals, which aren’t the best allies. This vague ‘we’.

LB: How do you judge Latvia’s previous participation in the Venice Biennale?

IŠ: This space we acquired in 2013 was a fundamental turning point. It’s too bad that the good exhibitions by Kristaps Ģelzis and Gints Gabrāns were exhibited outside the Arsenal. In addition, the former spaces had to be adapted quite a bit to accommodate art. I’m glad we’ve been able to extend the space for this exhibition, and that the space can be extended even further. Of course, I think that the organisation of the Venice Biennale should be delegated to a professional institution, such as an art centre, as it is in many other countries.

MF: I agree completely. The fact that the biennale is designated as public procurement makes the process simply absurd. The situations are straight out of Gogol. If it wasn’t so important, you could just distance yourself from it all.

IŠ: And the competition regulations should be changed, too, so that the artist isn’t forced to participate practically anonymously.

Miķelis Fišers, What Can Go Wrong, Latvian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. Photo: Mārtiņš Grauds

Miķelis Fišers, What Can Go Wrong, Latvian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. Photo: Mārtiņš Grauds

Miķelis Fišers, What Can Go Wrong, Latvian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. Photo: Mārtiņš Grauds

Miķelis Fišers, What Can Go Wrong, Latvian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. Photo: Mārtiņš Grauds

Miķelis Fišers, What Can Go Wrong, Latvian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. Photo: Mārtiņš Grauds

Miķelis Fišers, What Can Go Wrong, Latvian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. Photo: Mārtiņš Grauds