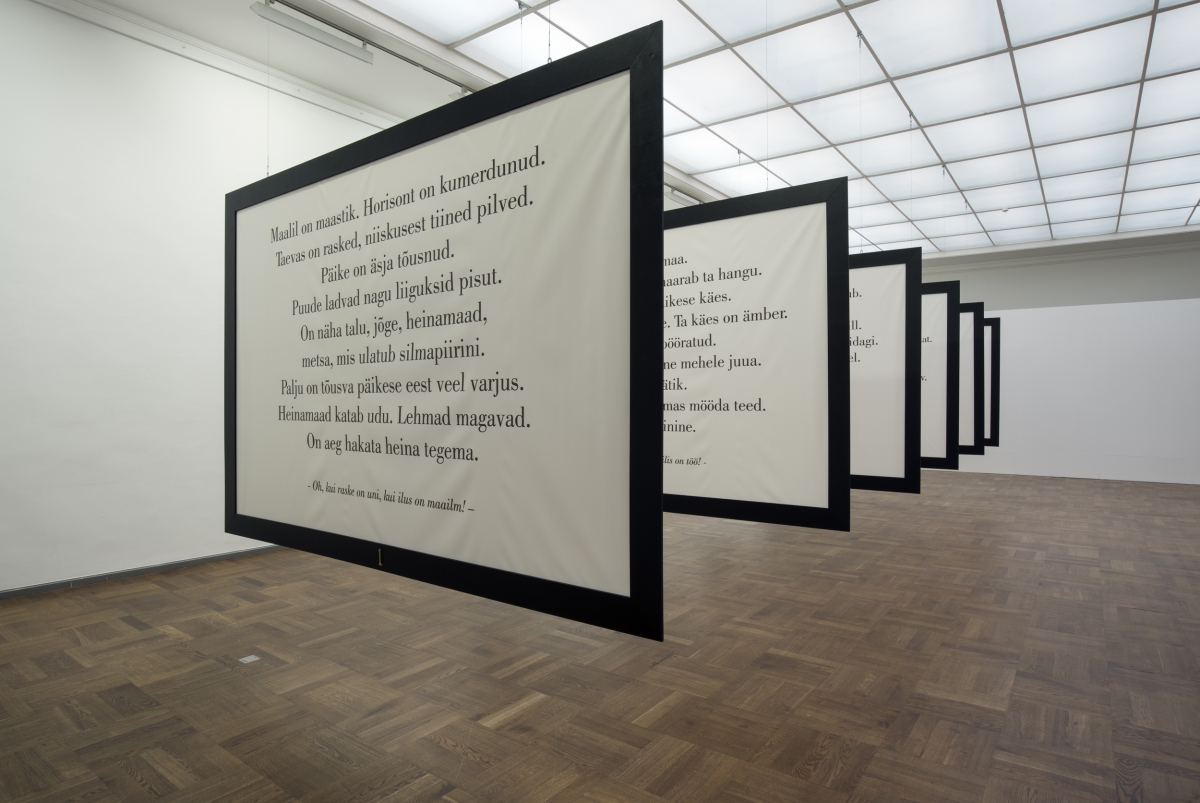

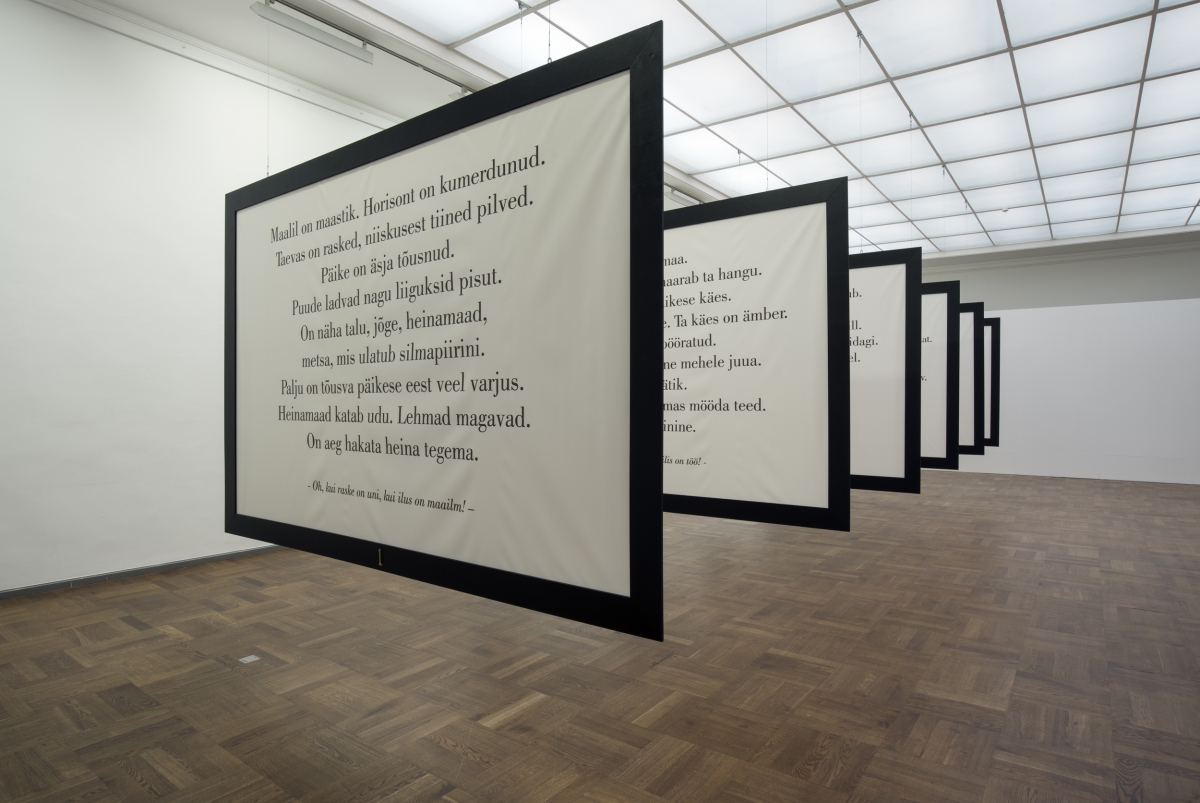

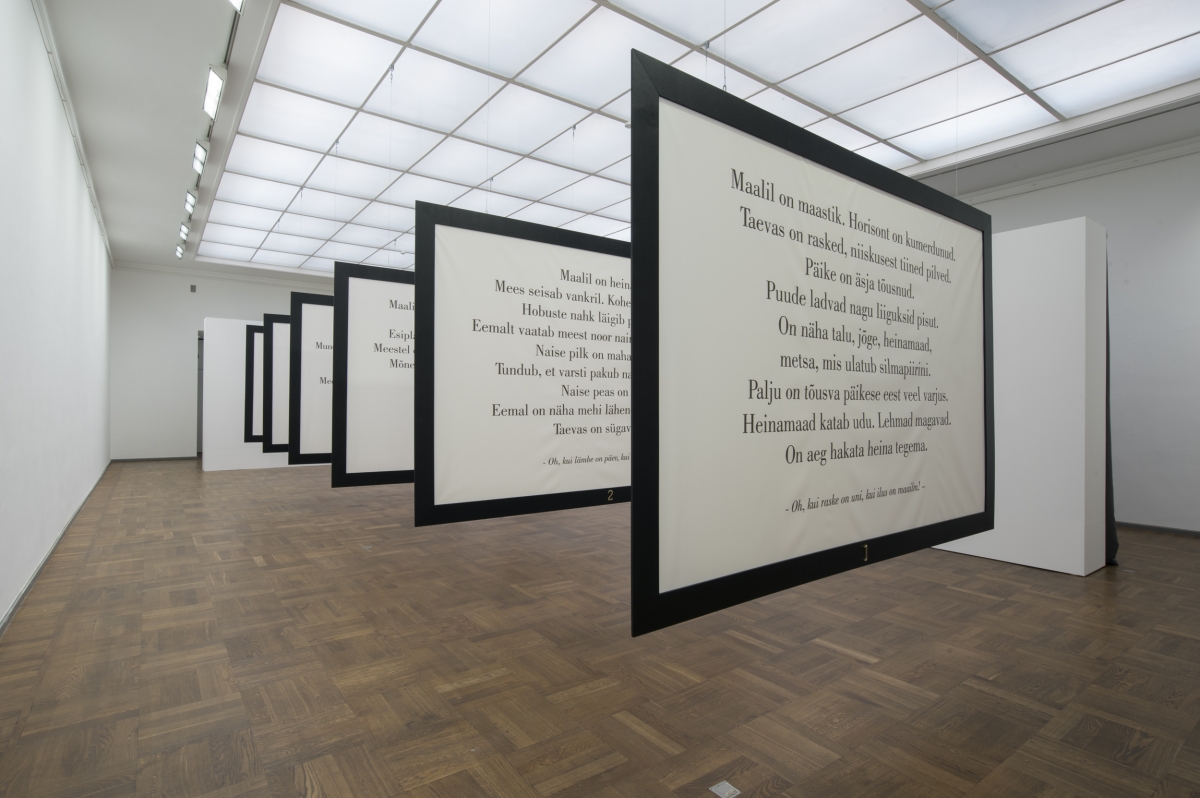

Andres Tali. Pastoral Pastiche. 6 digital prints on screen fabric, 300 x 200 cm. 2006

Courtesy of the Estonian Art Museum

The future is a riddle, and by starting to solve it we begin to shape it; trying to solve this riddle is understanding that the future is already happening and sooner or later we will find out about it, even if right now we do not want to know anything about it.[1]

– Hasso Krull

What will happen in the future? How to imagine what has not yet come into being? Neuroscientists have come up with the concept of the “prospective brain”, which explains that an important function of the brain is to use the information that is stored in episodic memory to imagine, simulate and predict future events. The psychologists Endel Tulving and Jüri Allik associate chronesthesia – the awareness of time and the ability to travel to the past and the future in your thoughts – with the uniqueness of being human. Furthermore, Tulving proposes the chronesthetic culture hypothesis, according to which humans must be aware of time and able to imagine the future, as only on the basis of this can they change their environment and act sustainably. The ability of the human brain to imagine the future messes with the familiar past-present-future linearity and allows for the future to change the present.[2]

But does this actually work and how? The current global nationalist and conservative political developments force us to think about the future. Can the past be used as a model for predicting the future? If so, what signs should be seen as meaningful? The US presidential elections, the attempted coup d’état in Turkey, the acts of terrorism in France and Belgium, the national conservatives in Estonia and Hungary – all of these seem to be real and serious symptoms. Hey, we can see where this is going, what is happening?! Is this what we really want? It is not, is it? But we are not doing anything about it because we live in a perpetual present that is relayed to us by technology and the media, where every tragedy is unexpected, yet unsurprising; shocking today, forgotten the day after tomorrow. The prospective brain has been collectively shut down, it seems.

The exhibition Silence. Darkness is an invitation to look at things from another angle, to step outside the inevitable past-present-future flow and acknowledge that the relationship between our notions and motivations and the wider context is changing and unstable. The passing of time has a ruthless effect on our past decisions, it exposes the unviability of our previous best intentions and forces us to re-evaluate, forget or distort them in our memories. For this reason, the works that Silence. Darkness centres on are not fantastical either; on the contrary, they delve into history. When visitors leap and reach into different layers of history, these continued excursions become the present and are actualised in the artworks that they are seeing at that very moment. The utopian visions and reflections on the past that the artists propose have great potential to become a model for some scenario of the future. The tension lies in the conflict between imagination and reality: “In researching the future, there is a constant dilemma between knowledge and hopes and fears. Our knowledge of the past and the present is the basis for looking into the future.”[3]

Ideology, utopia and perspective

This international exhibition in Tallinn Art Hall brings together the works of nine artists, whose topics include hoping for and imagining an ideal world, but also forever-inevitable change and ideological failure. The artists provide us with a cross section of the world, they discuss how East-German Marxism-Leninism lecturers were made redundant after the fall of the Berlin Wall, how artists make ethical choices and adapt under different rulers, the search for a capitalist business messiah, the animistic utopia in Africa and the realisation of a capitalist Utopia in a Tallinn suburb, the pattern of passing on the genes of ancestors and the potential developments of the romantic narrative.

If our goal is to see into the future, then it is also a question of the limits of our imagination and our modus operandi. Thinking of the future is most often described by metaphors related to sight: the future is ahead of us and before arriving at it, we should be treated to a sight of a clear panorama. In this case, seeing is an analogy for things becoming clear and imagination is the ability to form a mental image of something that does not yet exist. The system, whereby our memory relies on the past to check whether a vision is likely and what we imagine is realistic, is still functioning throughout all of this. Dreaming is a deeply ideological process, which brings out the discourse in which we think.

The social function of art is important here, art as a conveyor of memory and interpersonal reality. Art and visual culture in general, literature, and ideological narratives constantly provide us with material on which to draw in our visions. In a sense, culture also determines the standard vision of the future, its typical imaginary form, which is like an anchor or a lighthouse that starts to shape the vision of those whose fantasies are blank. “We live in a time when our capacity for imagination is actually manipulated”, the artist Marko Mäetamm observes in Dirk Hoyer’s interview film (Ap)Art (2015), which examines the relationship between artists and utopias. “We are programmed to imagine what they want us to or what is in the interests of big business. I feel our imagination and fantasy is becoming more constrained, rather than broader.”

How then to imagine the future? Inevitably, the concept of an utopia, which has suffered from overuse and loss of meaning in everyday conversations, is central also to this. Thinking about the future is a very creative process. Attempting to picture something that does not yet exist is similar to an artist’s creative work, in which they single out an image and do away with everything that is unimportant – everything that we can include in our mental image of the future is precisely what is the most important and creates meaning. A look into the future is always from central perspective, it is the vision of a single person from their own viewpoint.

Still, why is the exhibition titled Silence. Darkness, which tends to evoke closeness and scarcity, if humans have the ability to travel to the future in their minds, and the best intention to devise social utopias and move towards them; if there is knowledge and a readiness to learn from the past and make the best decisions for the future? In his film, Dirk Hoyer asks Estonian artists about social alternatives and potential future developments. This makes complete sense – who else than artists, who are sensitive to social conditions and informed in their analysis of them, could be oracles who see opportunities to change course and think outside the box in order to offer alternatives to the current state of learned helplessness? When the interviewees are asked what kind of an utopian vision they are inspired by, they are at a loss for words and the film also emphasises this. Looking into the future does not come easily. Their knowledge of actual circumstances, current politics and the global economy weighs heavily on them and they hesitate to talk, like Thomas More did, about a new way of life that is socially close to ideal or about a socialist realist nice sunny future that is already here. Perhaps the whole concept of the future is merely a scam and because it will never arrive, it is also impossible to imagine it? Or it will never arrive, precisely because it is impossible to imagine? We live in a perpetual present and we are not facing a bright panorama, but silence and darkness instead.

Anneli Porri

Silence. Darkness. If we know what was, do we know what is coming?

Exhibition at Tallinn Art Hall

27.08.—09.10.2016

Artists: Neïl Beloufa (FR), Kennedy Browne (IE), Phil Collins (GB/DE), Jaana Kokko (FI), Holger Loodus (EE), Kristina Norman (EE), Anna Škodenko (EE), Andres Tali (EE), Anu Tehver (EE)

Curator: Anneli Porri

Photography: Karel Kolimets

Andres Tali. Pastoral Pastiche. 6 digital prints on screen fabric, 300 x 200 cm. 2006. Courtesy of the Estonian Art Museum

Kristina Norman. Festive Spaces. Single-channel video with sound, 30 min, 2016. Courtesy of the artist

Kristina Norman. Festive Spaces. Single-channel video with sound, 30 min, 2016. Courtesy of the artist

Phil Collins. marxism today (prologue). Single-channel HD video with sound, 35 min, 2010. Courtesy of Shady Lane Productions, Berlin

Phil Collins. marxism today (prologue). Single-channel HD video with sound, 35 min, 2010. Courtesy of Shady Lane Productions, Berlin

Kennedy Browne. The Myth of the Many in the One. Single-channel HD video with sound, 19 min, 2012. Courtesy of the artists

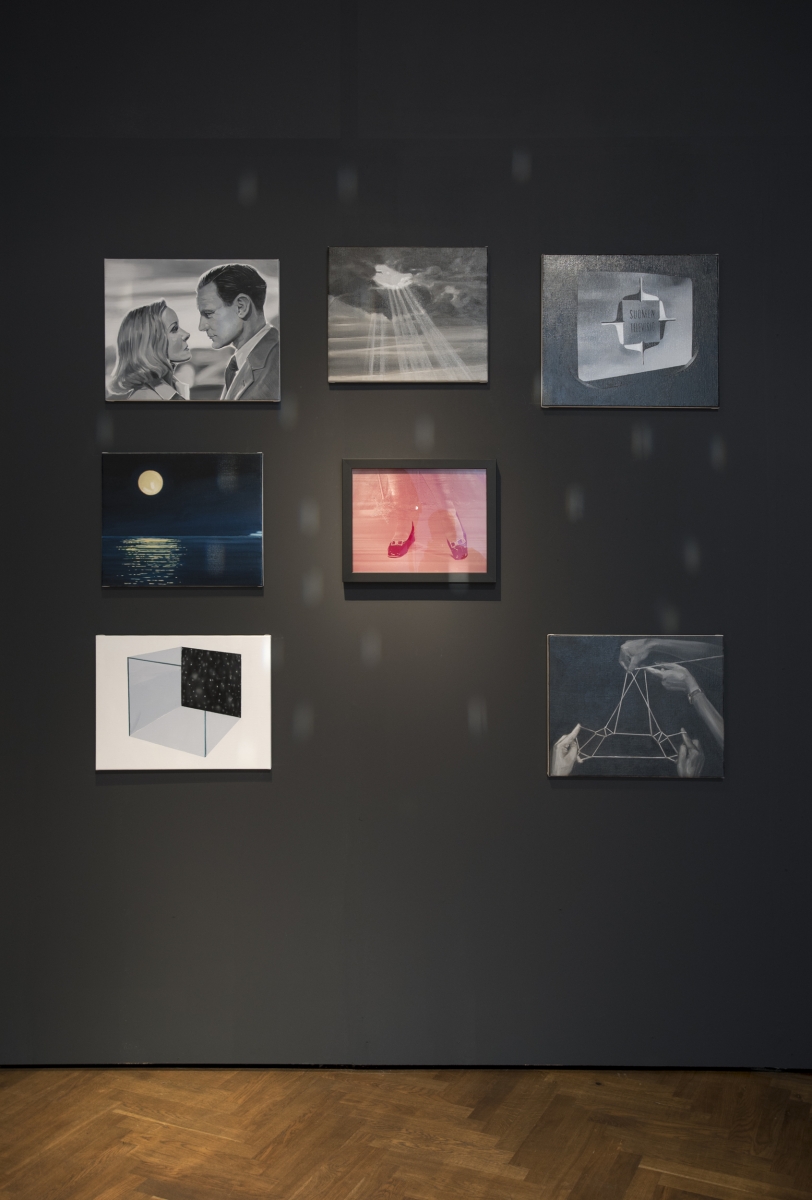

Kennedy Browne. The Wonder Years. Installation, 2013. Courtesy of the artists

Anna Škodenko. Idealistic. Oil on acrylic glass, acetone transfer, 100 x 200 cm , 2009, 2016. Courtesy of the artist

Anna Škodenko. Idealistic. Oil on acrylic glass, acetone transfer, 100 x 200 cm , 2009, 2016. Courtesy of the artist

Neïl Beloufa. Kempinski. Single-channel video with sound, 14 min, 2007. Courtesy of LIMA

Anu Tehver. Tissue Samples. Silkscreen on hand-knitted surfake, 64 × 81 cm, 2016. Courtesy of the artist

Holger Loodus. Three Scenarios with Eternally Falling Snow. Oil on canvas, acrylic glass, laser cut, copper, light, 38 x 50 cm, 2016. Courtesy of the artist

Holger Loodus. Three Scenarios with Eternally Falling Snow. Oil on canvas, acrylic glass, laser cut, copper, light, 38 x 50 cm, 2016. Courtesy of the artist

Jaana Kokko. What There Is to See? Single channel HD video with sound, 24 min. Courtesy of the artist

Jaana Kokko. What There Is to See? Single channel HD video with sound, 24 min. Courtesy of the artist

[1] Hasso Krull. “Mõista, mõista, mis see on?” – Vikerkaar, October, 2010. http://www.vikerkaar.ee/archives/12380

[2] Endel Tulving. Mälu. Tartu: University of Tartu Press, 2007, p 279.

[3] Krista Loogma. “Tuleviku-uuringud ja stsenaariumimeetod.” – Akadeemia, No. 3, 1997, p 548