In this sorrowful time that has afflicted us, any attempts to find a language and forms of expression we could identify with, which could deliver at least some sense of shelter and comfort, have become almost a necessity for our survival. Our human imagination can project the wildest forecast, contemplating our planet’s future in fifty to one hundred years from now even though there is little need to look so far ahead, for the death toll in the Mediterranean, human despair on the USA-Mexico border, the burning devastation of the Amazon and other present-day disasters are right here, right now, unravelling before our very eyes.

Meanwhile, despite much anxiety arising from reading these events on daily news bulletin, art events such as the Venice Biennale continue to attract a growing number of visitors – national pavilions are being produced, airplane tickets purchased, queues outside pavilions increasing as is the usage of single-use plastic cups regardless of the ecological concerns nearby exhibitions are often featuring as urgent. We currently live in a time when the art world, with its face of Janus, the ability, so to speak, to critically observe the surrounding world instantaneously transforming its suffering into an aesthetic adventure, is revealing itself in its full glory. Could this be the moment when the tools of art have been completely depleted?

While working on this article, it is impossible not to consider these questions regarding the participation of the Baltic States in the 58th Venice Biennale, the theme of which was May You Live in Interesting Times. Although taking part in large events on this scale is essential for small countries like us – the objects of this intention being to announce ourselves in the international art scene and become equal participants in the art community – each year, nationalistic overtones and different approaches utilised by every pavilion beget one question: how do we envisage ourselves on the stage of contemporary art?

For a while it has been common knowledge that, on a global scale, it is much better to position oneself in relation to a certain region, and yet every year we witness each country taking a slightly different approach. Each Baltic state allocates different amounts of funding to the arts, however reciprocated, with internal support and long lasting quality control (sometimes even over decades) in the hope that it might eventually pay off, as has been the case with the Lithuanian Pavilion this time around. Although the significance of awards could be debated, recognition on this scale is remarkable nonetheless because while the Baltics have never won the Grand Prix before, art from this region is becoming more renowned internationally. However, we must note there are several aspects that contribute to these so-called achievements in the art world, which stem from various circumstances that are often not related to art at all. For example, what happens after the award has been received – when hands are done shaking, words of recognition finished being uttered – when excitement and ecstasy has died down or faded away: do the lives of artists get any better?

Opera-performance ‘Sun & Sea (Marina)’ by Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, Lina Lapelytė at the The Lithuanian pavilion, 58th Venice Biennale, 2019. Photography: Andrej Vasilenko

The opera-performance Sun & Sea: Marina at the Lithuanian Pavilion was created by an all-female team: filmmaker and director Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, writer Vaiva Grainytė and artist and composer Lina Lapelytė, together with 20 participants and singers (whose names I cannot seem to find anywhere). The Pavilion was curated by Lucia Pietroiusti from the Serpentine Galleries in London. This multi-disciplinary project focused on climate change, highlighting global and ecological crises, the contemporary art scene included in that. Although the pavilion’s success affirmed the rise in popularity of performance as an art form over the last few years, it is also a much more expensive and time consuming medium of art than others. The conversation about what it means for artists to present their work in the current economic climate has only just begun. Included in that conversation is the question of how selfless work without appropriate remuneration invested in the Venice Biennale pays off later on and where the work will resonate most.

These are times of austerity in which most artists cannot survive or make an affordable living off their art alone. Furthermore, according to information already known about the Venice Biennale, it is predominantly funded by the big art market players with state funding never being sufficient enough to produce pavilions single-handedly. In terms of the Lithuanian Pavilion, its performance was originally only open to the public on Saturdays. This has recently been extended to also include Wednesdays. The curator Lucia Pietroiusti noted: ‘Going into the vernissage week, we didn’t have enough money to guarantee us until the end of the Biennale, even performing once a week’[i]. Is adventurism the new norm these days? Why is there still an expectation to produce works of art that their exhibitors cannot even afford to show for the duration? This year’s Venice Biennale clearly demonstrated insufficient amounts of resources for artists, producers, curators etc. coupled with enormous expectations to present high-quality artistic content and experience, which resembles gross entertainment demanded by the contemporary consumer, and is resonant of slave labour fuelled by the ambitions of these nations.

From what I have read and with whom I have listened to, the Lithuanian Pavilion is formidable and provides a very interesting format for this year’s Biennale. Yes, I did not see the performance because I was not there on a Saturday. Perhaps this is the reason I find it so interesting to contemplate the performance without having witnessed it, since I am wary of over-heightened emotions and pathos that people have employed when referring to it, and more so because the Venice Biennale has been so weak this year. Maybe events of this scale can no longer transmit the language of art to the viewer who has grown accustomed to experiencing art through digital means. The relationship between physical or real life experiences and the way they reverberate on our screens or social media accounts can no longer be separated. Maybe this is the reason the effect normally conveyed by a theatrical presentation and/or opera is so enormous which the Lithuanian team have been very successful at harnessing this year. I am also interested in the issue of this performance, based on the language of theatre, being developed with minimal financial aid and therefore forced to survive for the duration of the Biennale by only running one or two shows per week. How is it possible for such an event to acquire significance in the context of the whole Biennale? Or perhaps the opposite is true – the moment of presence and magic experienced during the performance after having to wait in the queue for two hours? In other words, what I mean by this is that the experience of art acquires a whole other meaning once your own time has been sacrificed. The exclusivity of art invites further reflection on the accessibility of art in our current time; although the art world addresses subject matter that affects, relates to and concerns each of us, the forms and expressions of art are becoming inaccessible to a growing number of viewers or, on the contrary, they become too accessible and no longer appear fascinating.

Saules Suns, Daiga Grantiņa, Pavilion of Latvia at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019.

Meanwhile at the Latvian Pavilion, Saules Suns, a collaboration between two organisations – Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art (LCCA) and Kim? Contemporary Art Centre – presents the work of Daiga Grantiņa, a Paris-based Latvian artist. It is essential to note that the Latvian Pavilion has finally made a commendable step forward by selecting to present contemporary art that is not just connected to the local Latvian scene. The pavilion, a partnership between the curators Inga Lāce and Valentinas Klimašauskas, presents a very poetic installation that depicts objects gliding through space in various relational and proportional arrangements to each other, casting conjoined light and material reflections and associations. In the accompanying exhibition text, Inga references architecture, i.e. J. G. Ballard’s sensory homes that adapt to their inhabitants, and links these aspects to Daiga’s work, whilst Valentinas examines the artist’s vision through the prism of transformation and assigns transformative qualities to it.[ii] As is the case with a lot of poetic and abstract work, these installations can be interpreted in many ways and each viewer can find something to relate to. It is interesting to observe that Daiga’s creative practice is dedicated entirely to the appeal of poeticism and aesthetics without considered attempts to embrace anything else in her work. What could this anything else be – socially political and ecological themes? Her work could be interpreted in the context of female art practice (as it has already been mentioned in several press releases – this year all three Baltic States have been represented by female artists), whilst also adding feminism to it. This work could also be perceived within the framework of abstract art traditions, although I doubt it has much in common specifically with Latvian history of art. Rather it is interesting to think of Daiga’s work as a meaningful choice in the context of contemporary art, when artist’s interests flow in an unexpected direction, when materials and relationships become the main subject matter and motivation behind creativity, irrespective of considerations relating to the choice of material, for example, are these materials good for nature and health or how vital is it to create new work in the era of overproduction? Additionally, what is the role of the language of abstract art within contemporary art? Does it carry enough power to speak to people today?

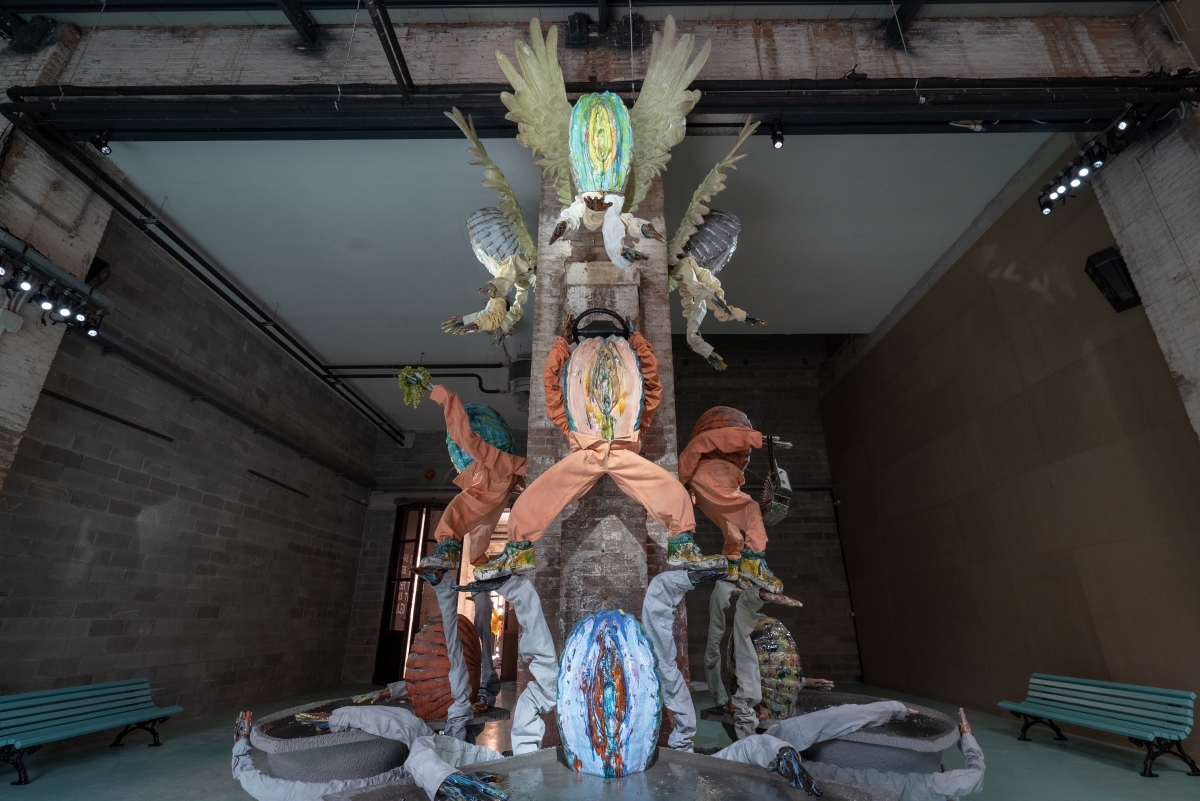

Exhibition view. Kris Lemsalu “Birth V – Hi and Bye”. Photo by Kent Märjamaa. The Estonian Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennial. Commissioned and produced by Center for Contemporary Arts, Estonia

Whilst thinking about the three Baltic art pavilions, I keep returning to the question: how do we look beyond the stereotypes we have placed upon ourselves and how do we avoid self-exoticism that still manifests itself as a tendency in representations from the Baltic States? Great expectations that we tend to have for ourselves and the resulting fear we might be misunderstood or not be good enough for an international audience, are present every time. In a way, the Estonian Pavilion has managed to avoid this with Kris Lemsalu’s work Birth V. The grotesque, clown-like character Lemsalu brings to life as her alter ego has already become her brand identity, reminding us of a misunderstood (mistaken) and excluded figure, of those who are different, and adapting her performativity each time she makes a public appearance. This year in Venice the artist has created a strange, phallus-like fountain installation. Its launch featured a performance, a decadently-odd presentation that was reminiscent of the traditions of Venice carnival, while also echoing pagan and ritualistic practices. Kris’s work always evokes mixed feelings – on one hand theatrical, unable to exist without an audience, and yet at the same time introverted, as if internally frayed and separate from everything else. Once again, the sculpture displayed in Giudecca, a neighbourhood on the outskirts of central Venice, leaves a rather absurd impression. Covered in vulva-like ceramic sculptures with wings, arms and legs, some even hold a basketball etc. making this sculpture appear more like a prop from a play. It seems that was also the intention of the pavilion, to focus on the Biennale opening days when it has the highest number of visitors – especially from the art world – emphasising the performance and presence of the artist over the exhibition’s structure, which will remain observable for viewers for the duration of the Biennale. This approach has almost become common practice in the contemporary art environment – the ‘special offer’ or the so-called spectacle art can be seen only for a few days when the exhibition is first launched with funders and VIPs present. But afterwards, the exhibition becomes ‘flat’ like an outdated poster informing us about something we have already missed. I would not want to imply that the presentation of the Estonian Pavilion is not interesting – it certainly is, and for me it is easier to view it in a wider context because I am familiar with Kris’ work, but what is it like for a viewer encountering Kris’s work for the very first time? That is what I thought about.

Although we all value and endeavour to experience the metaphysical presence transmitted by art, and its ability to move us and make us view things differently, unfortunately pressing structural problems and an abiding hypocritical, even cynical, attitude that has dominated the art world for decades is beginning to emerge. And this year’s 58th Venice Biennale is certainly one of the examples that attest to this. Despite the intriguing title May You Live in Interesting Times, controversy was stirred not only by Cristoph Büchel’s provocative work – the actual ship Barca Nostra on which at least 800 refugees have died – but also by the structure of Biennale. The main exhibition resembled an art fair without a cohesive conceptual line or at least different sub-themes, leaving the work of artists looking like they had been ‘thrown’ together largely ignoring mutual relationships. Thus, even strong works lost their individual voices in the struggle for attention. Because of this background, of course, pavilions geographically further away, like the Lithuanian Pavilion, which offered a unique experience stood out immensely. What is also worth remembering is that it is essential to be in the right place at the right time. Let us see how Lithuanian artists will apply this recognition and take this opportunity further.

[i] Elisabetta Povoledo, Their Beach Opera Won at the Biennale. But They Can Hardly Afford It, The New York Times, May 31, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/31/arts/lithuanian-opera-venice-biennale.html

[ii] Daiga Grantina, Latvian Pavilion Saules Suns, La Biennale di Venezia 58th International Art Exhibition. – Riga, Mousse, 2019.