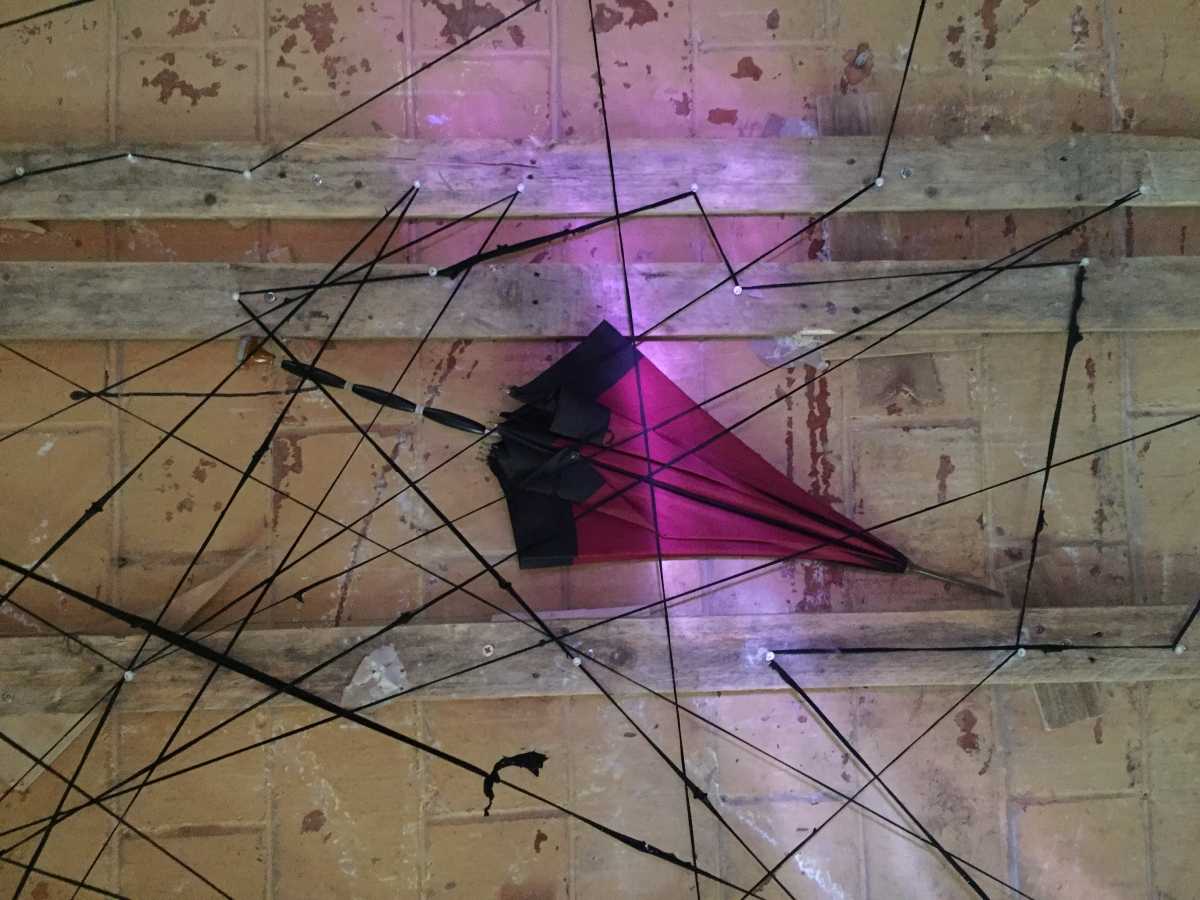

Installation including the video “Never forget to change umbrellas” (2009)

The exhibition ‘Roosa toss väljas’ by the Kraam collective was organised within the framework of the feminist LGBTQ festival Ladyfest. It was dedicated to the queer-activist Anna-Stina Treumund (1982–2017), whose death shocked the cultural and feminist scenes in Estonia and internationally. As someone who built bridges and brought a lot of people together, she was the heart of many discussions. For her final diploma work at the Academy of Arts, she presented a exhibition project ‘You, Me and Everyone We don’t Know’ (2010) that consciously sought to bring visibility to lesbian women. In her consequent work she provoked her audience to think further about the subordination of women, female sexuality, the social and psychological mechanisms of patriarchy, creation of otherness, the histories of queer subcultures in Estonia, and BDSM subculture. As an activist she was the initiator of popular feminist Facebook group Virigina Woolf is not afraid of you which grew out of a reading group, and one of the initiators of the feminist festival Ladyfest in Tallinn since 2011. She continued fearlessly to share what she believed in, breaking stereotypes and taboos on the way. The exhibition ‘Roosa toss väljas’ dedicated to her functioned as a kind of safe space. Safe spaces are rare, and that is what makes them so valuable. This is how I will discuss the installation-exhibition here, in order to look more broadly at the role of safe spaces, because it seems to be an important role that part of alternative culture has increasingly come to acquire.

Kraam is a collective consisting of Minna Hint and Killu Sukmit. It has been active in Tallinn since 2015. They have organised workshops, film nights, concerts and a free clothes shop. They toured east Estonian towns and villages with the last, and they plan to head for south Estonia this summer. More recently, Kraam has offered a platform for a critical discussion about asylum seekers in Estonia, bringing together information, and organising events and workshops to think collectively what can be done. To put it in a nutshell, they have taken on the role of bringing people together, and making the kind of discussions happen that otherwise would not have a platform.

Installation including the video “Never forget to change umbrellas” (2009)

‘Roosa toss väljas’ (literally ‘pink smoke out’) was organised as part of the Ladyfest festival dedicated to feminist motherhood. The exhibition’s title is a play on words: ‘toss väljas’ is an expression to convey the feeling of exhaustion or overwork, which here seems to be a reference to Anna-Stina’s untimely death, that brought a new consciousness to the Estonian art scene about depression and the importance of self-care. However, as pink smoke literally filled the space of the exhibition, it is a reference to the creation of a space that the artists called ‘the pink cube’ – a feminist space, a space for respect, care, commemoration, and empowerment.

The exhibition or installation consisted of many intimate smaller environments and installations, involving music, a video work, personal objects and clothes, which were brought to Kraam by the artist’s friends and relatives. Many of the themes in the exhibition involve stories about Anna-Stina’s passions, like having a child, BDSM culture, depression. On one side of the space, there is a broken white wall, from which pink light comes, and next to the rubble there is a length of tape with the message ‘GENDER CHECK’ written on it. In another installation, a sewing machine fills a maxi-cosi children’s car seat. There are red boots hanging from a hanger with a black rivet belt, on a construction made from a high baby feeding chair and a large dark-red mattress. Many of the smaller installations create unexpected connections between things we are not used to seeing together and which are nevertheless connected in her interests.

The video work Never forget to change umbrellas (2009) records a meeting in an airport between Anna-Stina and Minna. In it, they run towards each other with open umbrellas, hug each other warmly, and swap the umbrellas they carry. The work is screened on to a canvas, which has a message from Anna-Stina embroidered on it with white thread: ‘I have two families: a biological one, and a political, queer-feminist, one.’[1] The two works enter a dialogue with each other, and this might explain why the artists consider Anna-Stina to be one of the authors of the exhibition.

A view to the pink space of “Rosa toss väljas” including the smashed white wall at the back.

From the ceiling hangs a pink Ladyfest banner, with two fists targeted at the viewer. On the sofa there is another banner: ‘The world has to be filled with lesbians!’ On the back of a pink row of chairs, we can read the message ‘SUCK ME!’ There are many more important details relating to personal stories that the space allowed to share, such as Anna-Stina’s clothes, books and records that friends borrowed from her but can never return. On the last day I visited the exhibition, another beige leather skirt borrowed from Anna-Stina during her lifetime was brought to Kraam, suggesting that her energy is alive, because, as the theorist and critic Airi Triisberg wrote, her role as a community creator is continuously present.

Apart from being a safe space, it seems that the exhibition functioned as a therapeutic space. It was therapeutic in that it allowed us to reflect on this loss to the whole Estonian art scene, the feminist and gay scenes. In that one year after Anna-Stina took her own life, it allowed and provided a space for grieving and acceptance. One of the artists, Killu Sukmit, told me that several visitors to the exhibition had mentioned to her that although they were cautious about what they might encounter before coming to the exhibition, in hindsight they actually experienced the environment as a relieving one.

With her dedication, honesty and sharp analytical skills, Anna-Stina Treumund gave birth to so many important conversations. One of the urgent conversations that the exhibition ‘Roosa toss väljas’ brings to mind, which is waiting to be held on the art scene, is centered around mental health and the importance of self-care and care for others in a context where depression is so widely legitimated. What does it mean to collaborate with someone suffering from depression? How can friends and professionals take this into account? What are our responsibilities towards each other? How can we care? Its neglect seems to have a certain Soviet air to it in Estonia, where professional care for depression itself had a dubious role, having once served the structures of power and repression. Holding such a discussion can only be initiated in a safe space, hence the importance of safe spaces for those suffering from depression, and for those close to them. With a growing amount of people suffering from depression the topic concerns us all, and hence, we need to start this conversation.

Installation with a Maxi-cosi and a sewing machine.

Installation with high heels and a row of chairs.

Installation with pink boots that belonged to Anna-Stina Treumund. According to Killu Sukmit they mark the footprint of the artist, and transmit the idea of being on the way, making one’s mark, and kicking the door open.

[1] This message was the first sentence in Anna-Stina’s essay ‘Foremothers’ published in Archives and Disobedience: Changing Tactics of Eastern European Visual Arts (2016).