Opening of the exhibition. Photograph by Mārtiņš Otto, Rīga 2014

This summer the group exhibition “(Re)construction of friendship” was site-specifically installed at the Corner House in Riga, the main building of the State Security Committee (SSC) until 1991 and one of the key attractions of “Riga 2014”. The mediated reconstruction of the past often plays a major role in these kinds of memorable places. Thus on the first floor of the Corner House one finds these dramatic headlines, amateurish, bad quality black and white photographs and sketchy stories furnished with chronological timelines, historical facts and personal accounts reminiscent of the typical memorial museum’s display. After two floors of multiple affective loadings as well as three empty ones you enter the sixth floor where the “(Re)construction of Friendship” exhibition is placed – turning out to be a strong counterpoint to the touristic expectation.

In the preface of the exhibition catalogue, entitled “Where’s friendship”, two of the exhibition curators – Aesa Sigurjónsdóttir and Kārlis Vērpe – formulate the project’s key question: “Does the dubious ‘friendship’ highlighted in the exhibition only arise under totalitarian regimes and can it be set into relief against the eternal enlightenment project of the Western world?”((Aesa Sigurjónsdóttir & Kārlis Vērpe, ‘Where’s friendship’, in: Kārlis Vērpe, Draudzības (re)konstrukcija / (Re)construction of friendship, Riga: Art space 2014, p. 9.)) The answer proposed in the artists’ works is clearly a “no”. Dubious ‘friendships’, strategic and (in)official alliances between two parties, certainly also appear in the “former West” and can both be created and found in the present – far beyond the Soviet system. Here, we are facing the core of this exhibition’s conceptual outline: the research on what these ‘friendships’ were/are, how they were performed, and what role they inhabit in the post-socialist and “pOst-Western”((This goes back to the German term ‘pOst-Westlich’, which emphasizes the constructedness of the ‘East’ and ‘West’ and combines these concepts. The ‘pOst’ implicates that not only the ‘East’ but also the ‘West’ has changed. For more information, see Elize Bisanz, Diskursive Kulturwissenschaft, Analytische Zugänge zu symbolischen Formationen der pOst-Westlichen Identität in Deutschland, Münster: Lit Verlag 2005; Marlene Heidel & Elize Bisanz, Bildgespenster. Künstlerische Archive aus der DDR und ihre Rolle heute, Bielefeld: Transcript 2014.)) present.

As the discursive attachment to the old opposition of totalitarism vs. democracy inscribed in the confrontation of ‘East’ and ‘West’ renders deeper analyses an impossibility, most artists were transgressing national and geo-political borders though never denying their culturally preconfigured gaze – like for instance the artist, writer and critic Tanel Rander (*1980) who is showing a photography, video and text based installation. His photography series “No Borders” (2013) included a ‘snapshot’ of the open Latvian-Estonian border, depicting a two-channel banner, an image to the left, and a text to the right saying “No Borders! Next Stop – Parnü!” in Estonian, English and Latvian. The image is the “M” of the fast food restaurant McDonald’s in the familiar corporate font, surrounded by an equally well-known circle of golden stars on a green background. The flag of Europe, symbol of the European union, orbits around a global icon which represents profit-oriented policies, expansion, exploitation, cultural homogenization and entrepreneurial rationalization (see George Ritzer’s “The McDonaldization of Society”), – next to huge letters proclaiming “No Borders!”. This perfidious image symbolically crystallizes the dilemma of many individuals, groups, areas and regions in Europe and elsewhere: the global dictatorship of the capital causing dramatic effects on people’s lives and mobility and therefore performing new geographical borders – bound to ecological resources, technology and average loans. In his equally political and outraged texts, Rander summarizes: “Friendship means business, capital means segregation”.

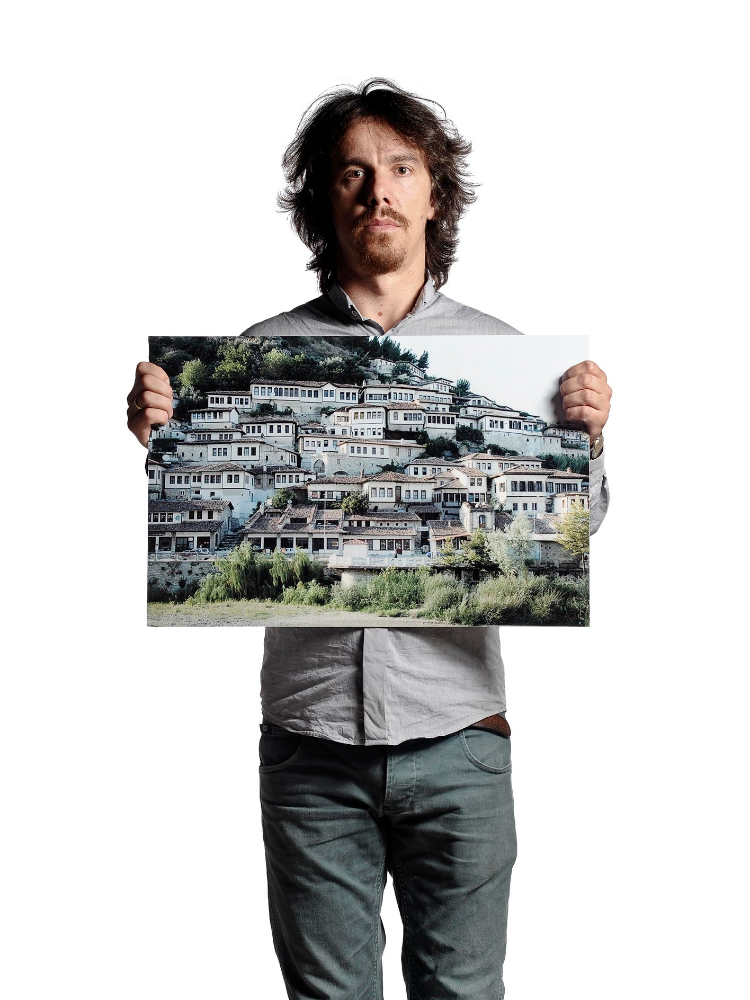

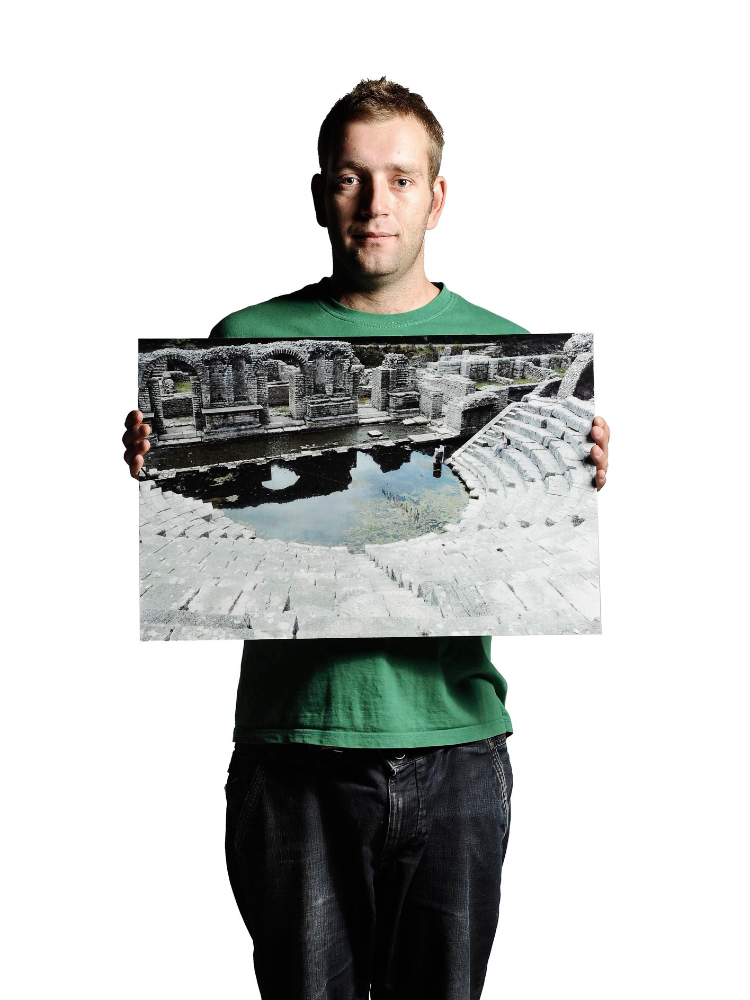

After this heated example I want to take a look at the photographic series “My Name Their City” (2012) by artist and filmmaker Alban Muja. Based in Kosovo, he investigates socio-political themes connected to local histories, like in “My Name Their City”, where he asked young Kosovan adults, born during the 70s and 80s, whose parents gave them names of Albanian cities, to hold “their” city’s postcard into the camera. Although these oversized, anachronistically looking city postcards only have a pure linguistic connection to their carriers, the young people’s serious expressions reflect the phenomenon of collectively naming one’s child after the city that one feels related to – but is prohibited to visit for decades. Through these staged photographs Alban Muja reminds us of a political reality that affected this group of people so deeply that they inscribed the loss of their home country literally ‘in the name’ of their kids, who thus became ‘actors’ in the tragedy of “insurmountable borders until the 90s”((Aesa Sigurjónsdóttir & Kārlis Vērpe, ‘Where’s friendship’, in: Kārlis Vērpe, Draudzības (re)konstrukcija / (Re)construction of friendship, Riga: Art space 2014, p. 9.)).

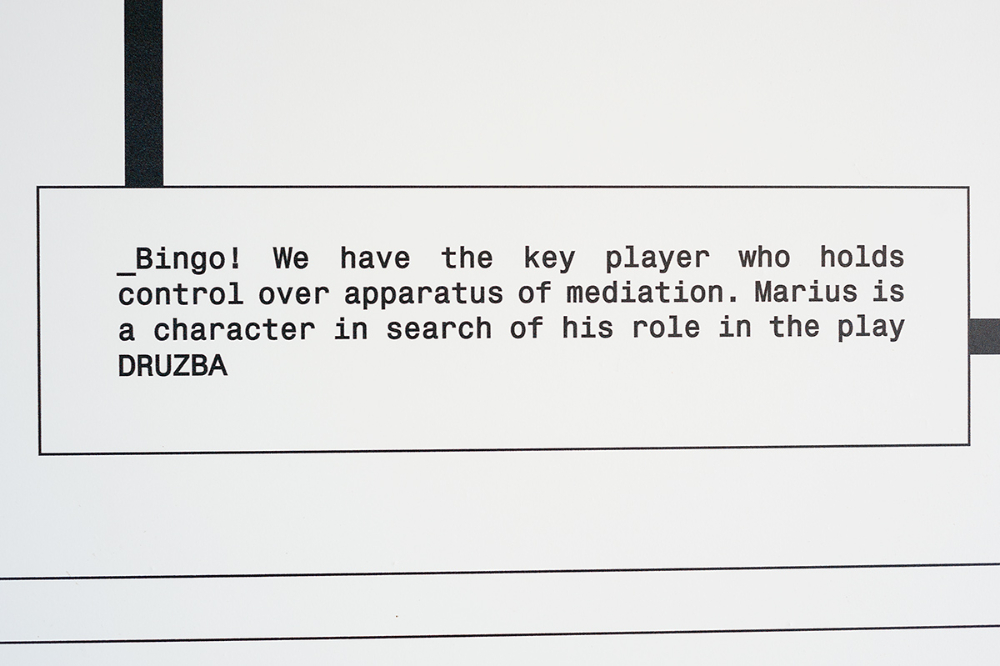

Another iconic work in the exhibition is “Družba” (Russian word for ‘friendship’), an ongoing research project and multimedia installation by Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas that started in 2003. This installation couldn’t be placed better than here – in a former SSC headquarter, where the performative power of the word in Soviet culture((To read more about the textual performativity as a cultural practice: Sylvia Sasse, Texte in Aktion. Sprech- und Sprachakte im Moskauer Konzeptualismus, München: Fink Verlag, p. 24.)) got ensured and controlled. “Družba” is the biggest oil pipeline built by the Soviets in the 1960s and 1970s to transport oil some 4.000 kilometers from Russia to the Baltic States, Ukraine, Belarus, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Germany. After the dissolution of the socialist states and the fall of the Soviet Union this large artery for the transportation of Russian (and Kazakh) oil across Europe was privatized. Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas consider “Družba” as a huge symbol for the sociocultural effects of Soviet politics in Europe. Preparing a “psycho-geography of the oil network”((See the short description on Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas website: http://nugu.lt/dossier/index.php?mid=224 [latest access 22.09.2014])) they conduct a fictional travel to each (in)significant station and branch of Družba, drinking coffee, chatting with locals and occasionally writing their dairy. The installation is characterized by a geometric black architecture with small monitors screening video material from the Lithuanian Film Studios and Lithuanian Central State Archives, including educational videos like scenes depicting ‘teachers at work’, propagandistic videos of Soviet industrial companies as well as a filmic ‘play’ with African-like masks. The three videos literally ironize the ritualized procedures and speech acts of authoritative discourse((Alexei Yurchak, Everything was forever until it was no more. The last Soviet generation, Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press 2005, p. 21.)) during Soviet time; they are surrounded by wallpaper with archival images and associative personal accounts constellated and arranged in a fake, neurotically precise timescale.

A conceptually and formally very convincing work is Sandra Krastiņa’s newly produced piece “Archive Unit” (2014), comprised of five oil paintings on paper directly attached to the walls of the Corner House. This work refers to an uprising in Soviet labor camps in Kengir from May 16 to June 26, 1954, which is described in the exhibition catalogue: “During the uprising, the prisoner’s gained control over the camp territory: they drove out the guards, laid down their requirements to the prison authorities, broke down the wall between the man and the women sections, founded a self-government, and began to devise self-defense tactics. Parallel to these organizational activities, inmates of various nationalities searched for one another to talk about home; naturally, men and women met, fell in love, danced and sang, because autonomous folk groups even existed – until one night when armed guards in tanks invaded the camp.”((Sandra Krastiņa & Kristaps Epners, ‘Uprising’, in: Kārlis Vērpe, Draudzības (re)konstrukcija / (Re)construction of friendship, Riga: Art space 2014, p. 49. ))

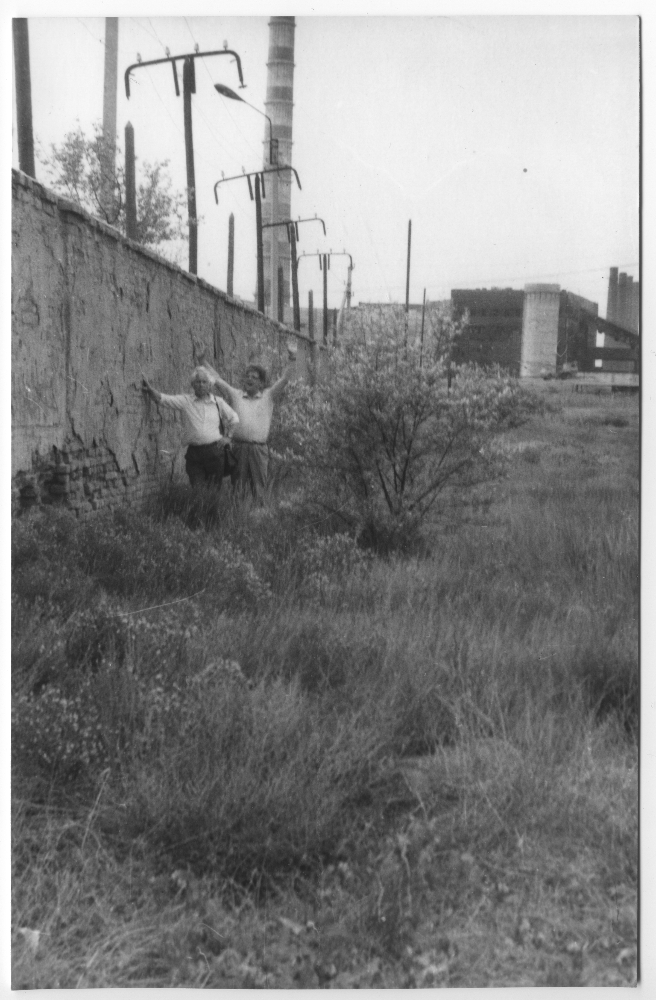

For her piece Krastiņa utilized a low quality photograph of the early 90’s depicting two elderly men visiting the camp 40 years after the event. The two white men are standing against a wall, looking into camera whilst one – surprised or in panic – is raising his hands. Krastiņa appropriated this photograph for her conceptual wall paintings, sensitively experimenting with its documentary quality and the relation between painting and photography. In “Archive Unit”, this “near-documentary” status((By the term “near-documentary”, photographer Jeff Wall described an image regime which is ambivalent about the veracity of what it describes.)) of the photograph is analyzed by zooming into the visual field and creating different cutouts. Using rusty-colored paint, Krastiņa turns the amateurish, antimemnonic photography into a memory image by means of an “almost auratic rendering” of the banal which, according to Hal Foster’s remark about Gerhard Richter’s paintings from photographs, takes place when “life gets congealed into an image”.((See: Hal Foster, ‘Semblance According to Gerhard Richter’, in: Benjamin H. D. Buchloh (ed.), Gerhard Richter, London, England: The MIT Press 2009, pp. 113-134 (here 121).)) In the wall paintings the two men are portrayed without faces, marked with a disturbing “blur”, carefully inserted by Krastiņa. Although the chosen photograph is not linked to resemblance and depiction, the five paintings still seem to successively shatter it.

In another room, together with Kristaps Epners, Sandra Krastiņa has built a huge, protruding metal cube, reminding of Christian Boltanski’s metal-based archive installations – with the slight difference that here the sculpture is an abstract object in space that is impossible to enter. This site-specific installation, entitled „Uprising“ (2014), encases the floor’s outside wall and navigates the visitor through a narrow corridor that ends up in a room’s corner: opposite to a private photograph of an old man standing at the very same wall which dissolves in Krastiņa’s fifth painting (from left to right). This “lost”, amateurish photograph gives no incontrovertible evidence of anything but its distanced, ‘touristic’ relation to the uprising. In this physically distressing and claustrophobic architecture, no questions get answered neither about the photograph’s age, its source, the man’s identity nor about his relation to the uprising.

The exhibition accomplishes to illuminate the “pOst-Western” condition, the end of the blocs, the dissolution of oppositional thinking, and the passage into a time when either/or-, friend/enemy-, own/foreign-schemes and dichotomies are overcome.((See: Elize Bisanz, Diskursive Kulturwissenschaft, Analytische Zugänge zu symbolischen Formationen der pOst-Westlichen Identität in Deutschland, Münster: Lit Verlag 2005, p. 7.)) Considering that the invited artists come from various countries in Europe (Estonia, Germany, Iceland, Kosovo, Latvia, Ukraine, Sweden) and the USA, it creates a new discursive space which captures still unknown histories, may it be about the military relationship of Iceland and the USA (Spessi & Erik Pauser, Base, 2003/2014) or about the atmosphere of the interrogation rooms of the STASI (Daniel & Geo Fuchs, Stasi – Secret Rooms, 2014), and – most relevant aspect for this article – reinterpret the abstract concept of a ‘true’ and ‘noble’ friendship as a freely chosen association in contexts in which it becomes inconsistent, fake (e. g. Tanel Rander, No Borders, 2013), utilitarian and even ridiculous (e. g. Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas, Družba, since 2003). In the artworks introduced, ‘friendship’ is characterized by the utilizations of virtues, recruitments, enforcements and takeovers – under the sheer appearance of partnership, reciprocity and equality. These conceptual ‘reconstructions’, performed by the artworks in the exhibition, emphasize visual art’s capacity to appropriate past elements, whilst embracing uncertainty, transience and incompleteness. Starting from ‘dubious friendships’ in totalitarian regimes, it creates a mnemonic stage for a “feeling of uncertainty”((Artis Ostups, ‘About the picture of history’, in: Kārlis Vērpe, Draudzības (re)konstrukcija / (Re)construction of friendship, Riga: Art space 2014, pp. 39-42 (here 43).)), causing great epistemological doubt.

For more information about the exhibition see here.

Interview with Inese Baranovska

(Re)construction of Friendship, exhibition view. Photograph by Martins Otto, Riga2014

Sandra Krastiņa & Kristaps Epners, Uprising, 2014, installation. Photograph by Janis Nigals

Sandra Krastiņa & Kristaps Epners, Uprising, 2014, installation. Photograph by Janis Nigals

Sandra Krastiņa & Kristaps Epners, Uprising, 2014, installation. Photograph by Janis Nigals

Sandra Krastiņa & Kristaps Epners, Uprising, 2014, installation. Photograph by Janis Nigals

Sandra Krastiņa & Kristaps Epners, Uprising, 2014, installation. Photograph by Janis Nigals

Sandra Krastiņa & Kristaps Epners, Uprising, 2014, installation. Photograph by Janis Nigals

Sandra Krastiņa, Archive Unit, 2014, paper, mixed media, canvas, oil. Photograph by Janis Nigals

Sandra Krastiņa, Archive Unit, 2014, paper, mixed media, canvas, oil. Photograph by Janis Nigals

Sandra Krastiņa, Archive Unit, 2014, paper, mixed media, canvas, oil. Photograph by Janis Nigals

Tanel Rander, No Borders, 2013, series of photographs

Alban Muja, My Name Their City, 2012, series of photographs

Alban Muja, My Name Their City, 2012, series of photographs

Alban Muja, My Name Their City, 2012, series of photographs

Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas, Družba, 2003 ongoing, multimedia installation, 3 min 48 sec, 2 min 08 sec, 1 min 17 sec

Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas, Družba, 2003 ongoing, multimedia installation, 3 min 48 sec, 2 min 08 sec, 1 min 17 sec

(Re)construction of Friendship, exhibition view. Photograph by Martins Otto, Riga2014