by Šelda Puķīte (Riga), Valts Miķelsons (Riga) and Indrek Grigor (Tartu)

In one of his most famous pieces, “Things” (exhibited in the attic of Tartu Art House 19.03.-06.10. 2012.), Jevgeni Zolotko worked on the idea of the physical world being pure and innocent, as he himself claims in the interview given to Rael Artel on the occasion of the exhibition “Lukewarm. Prologue” held at the Tartu Art Museum (18.12. 2013 – 09.03. 2014). But, as he also states, it was for him foremost an ethical question: “The way in which we relate to the material world defines us, not vice versa”.

The exhibition “Lukewarm” continues to explore the same question. The exhibition space consists of three dominant elements. A video mimicking a fictive science show for children, a set of pencil and watercolour drawings of ancient Greek sculptures and a row of three sinks with mirrors above them, forming a triptych, which is all accompanied by an audio-mantra of (proper) hand-washing instructions.

Unlike most of Zolotko’s previous exhibitions, “Lukewarm” is very choreographed and “talkative”, meaning that the symbols generating the story in the exhibition space are open to interpretation, and the story itself very straightforward. So even though in the aforementioned interview Jevgeni opposes his practice to the straightforwardness of propagandistic posters, posing as an example the famous “Don’t blabber”, his work does literally blabber this time.

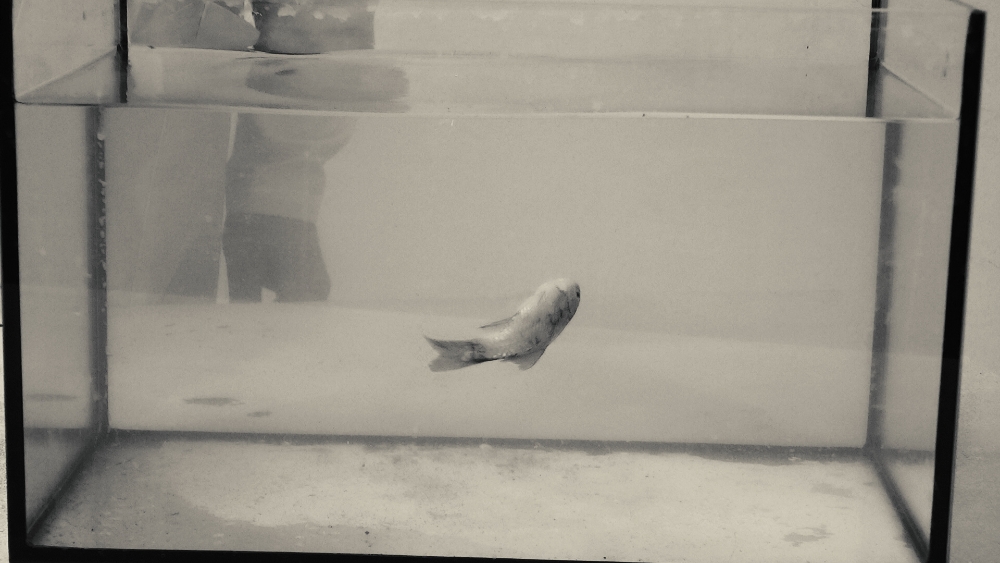

In the video, a man in a white lab coat presents to the “children” who observe the show a “magnificent experiment” that illustrates the “sustainability of life in extreme environmental conditions”. First, he puts a fish into liquid nitrogen, showing the icicle to a child, who looks rather scared, declaring that “literally – the fish is not alive anymore”, but puts it then back into the aquarium where it immediately revives. In the context of religious symbolism or imagery, characteristic of Zolotko, the events referred to are clear. The televangelist is telling us the story of Christ’s crucifixion and revival, which in this context works as a metaphor for the belief in the possibility to re-establish the eternal beauty and truth of a holistic world, which has been corrupted. And we all are guilty of this crime, as is clear from the instructions of how we must wash our hands, which fills the exhibition space, also becoming the soundtrack of the otherwise muted video. Even though the viewer is addressed as a child, it is clear from the bloody hand towel hanging next to one of the three sinks that everything goes by the book, and as Pontius Pilate couldn’t so we cannot wash the guilt from our hands.((In the Gospel of Matthew, Pilate washes his hands to show that he was not responsible for the execution of Jesus.))

But the intriguing thing in this situation is the man in the white lab coat, who is like a kind of neutral observer or objective grownup. How did he take this position? What gives him the right to patronise us? Bringing up the question of whether the artist implies that with this being the prologue, he intend to actually tell us the truth in his next exhibition? But then it turns out that the televangelist, is a two-faced man, he tells us the truth, and we believe him, because we do believe everything that is said on TV. Our corruption lies in believing the authoritarian/authorial voice. We cannot get our hands clean precisely because we are told to do so. In the interview Zolotko admits his own corruption – we should not believe him – “he has lost his virginity” working on the theme of lukewarmness. A fact that is again very symbolically signified by the bloody towel next to the sink.

The dialogue between the “authorities” is accompanied by the series of watercolor drawings of ancient sculptures. At first glance, they seem to stand for the eternal truth of beauty. But on second look they start to reveal more and more hidden layers. The background of the drawings is the same rusty-red colour as the stains on the white towel, which presumably is symbolising blood. So it establishes the opposition of pure white and colour, whereas Zolotko himself is known for working in grey, which physically is not a colour at all. In the interview with Rael Artel he comments on lukewarmness or neutrality, which is the leading theme of the exhibition: “There are only very seldom totally black or white situations… Maybe in this grey time the most important things take place? Not in dramatic situations or days of happiness, but in this grey everyday… From the theme of neutrality arises the question, what does neutrality mean in an ethical sense? You are not against evil nor are you for good.”

As we know, the general belief of ancient sculptures having been white is not correct – just as contemporaries of Pilate, they were once colourful. Through millennia, the authoritarian voice of historical truth has tried to wash off the blood from its heroic story. But the stains on the glass protecting the drawings prove the impossibility to hide the truth, which as we know from the video, can survive “extreme environmental conditions”. On a further level, and this might be an overinterpretation, it seems to be more than a coincidence, that the ancient sculptures often lack their hands. And, as everyone who has ever visited a sculptor’s studio knows, there is no dirtier profession. So the theme of washing one’s hands becomes, in the context of Zolotko himself being a sculptor, even more symbolic.

Despite the apparently brutal self-criticism that Zolotko is putting himself through, the longing and with that the hope and belief in the possibility to re-establish a holistic truth is ever stronger. So, as the title of the exhibition suggests, it is an introduction, a prologue to the next upcoming exhibition which opens on March 30 in Noorus Gallery, Tartu. “I want to be more and more precise. Even the way I speak. I say one thing and have then to specify it and then even more and even more… It’s like a journey to the horizon, it is endless.”

While the endeavour of the artist may indeed invite some cynicism, the monumentality of the symbolic stories that Zolotko is telling is impressive.

Photographs by Indrek Grigor