Exhibition view. Photo by Arnis Balcus

The role of photography as a document is constantly overrated. The role of camera in photography is also overrated. Yes, of course, we could agree about the indexical nature of photographic images—camera always captures whatever is before the lens. But what is being produced is an image, a confusing and treacherous one. Whenever we talk about the realism of photographs and how wonderfully this or that photograph has captured “life,” “moment,” or “truth,” we are being betrayed by the image. We are led into forgetting that we are looking at an image, an artificial and constructed piece of visual information. When we look at a photograph and see what is depicted, we overlook the materiality of the photograph itself. Perhaps all we need to know about photography was said already before photography became a subject for art historians’ debates. “This is not a pipe” (Ceci n’est pas une pipe), wrote René Magritte on his painting The Treachery of Images (1928-1929) that depicts a pipe. Accordingly, when we look at a photograph, we should see a photograph, not only the subject matter. “Experimental,” “alternative,” and “manipulated” are just some names given to numerous photographic practices that bring into focus the materiality of a photograph or the apparatus that produced it. Recently, Robert Hirsch has established a new term, “handmade photography.” This is the kind of photography that interests us here.

According to Hirsch, the difference lies in the verb: either one takes or makes a photograph.[1] Taking a photograph would refer more to the default mode of the function of the photographic apparatus. In the taking mode, the photographer selects a moment out of the time continuum and selects and/or arranges the space and the people. The photographer, no doubt, manipulates the camera and the printing process, but these manipulations become invisible because the resulting image appears so “realistic” and recognizably “life-like”. The medium of photography seems to dissolve before our eyes as if we were looking at the subject directly. To put it in other words, in taking a photograph the medium of photography and photographer’s labor must be concealed. Making a photograph, on the contrary, will inevitably make visible some part of the photographic process. The subject matter of such photography often is photography itself. The photography that is made, not taken, often explores and expands the limits of technology, like the early work in color photography such as the autochromes by Eduards Gaiķis (c. 1918). If you want to see good (or artistic, etc.) photographs of flowers, you go somewhere else. The fact that Gaiķis took these photos of flowers is not especially interesting. Instead, these images are valued as rare examples of early color photography made by a Latvian photographer.

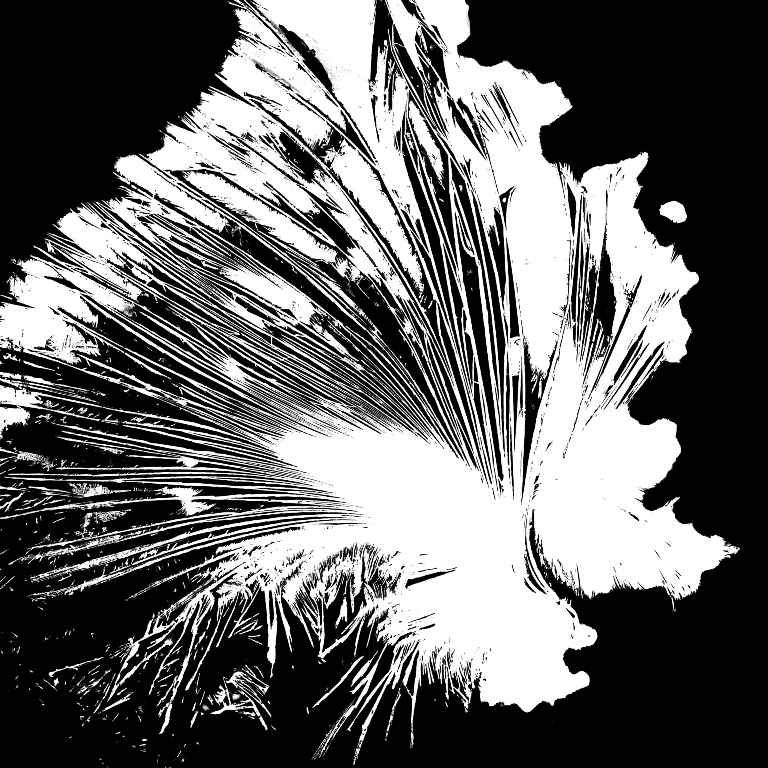

When photography is made, not taken, the subject matter can become completely irrelevant or even non-existent. Although it is a taboo to talk about abstraction in photography, this term is the closest to describing the vortographs of Alvin Langdon Coburn (c. 1915) as well as the large color prints by Wolfgang Tillmans (c. 2008). Some camera-less techniques also can produce photographic images that are quite abstract. For example, with the series of Crystallographs (1964-1968) by Valters Jānis Ezeriņš, the image was produced first by liquid developer (hydroquinone and metol) drying out on a glass plate and then by the photographer making gelatin silver prints from these plates. Nothing taken, all is made.

The making of photographs came to the foreground in theoretical writings just as the digital process gradually became the leading photographic technology in practically every field. For many in the 1990s and early 2000s, the realization that digital photography is “immaterial” was shocking—there’s just zeros and ones, this is just a computer file, and it is stored on a cloud. Soon things got even worse with the advent of social media and the massive popularity of cellphones with built-in cameras. The end of the old world of photography was symbolized by events such as the bankruptcy of Kodak in January 2012, and the beginning of a new one—by the inclusion of the word “selfie” in the Oxford Dictionaries of English and announcing it to be “the international Word of the Year.”[2] Now, everybody is a more or less decent photographer, and all photographs are on Instagram or somewhere else online. The cameras as well as the algorithms at work in smartphones tend to get better and better, letting anyone take decent quality snapshots in a totally automatic mode. It may seem that the leading method of popular photography then is taking photographs. Yet an opposite trend also exists: for example, many of the selfies are carefully made, not simply taken, just as numerous other genres of popular photography on Instagram.[3] On this background of popular photography, some practices stand out that are more oriented towards the materiality of photography. There are photographers who return to, or revive, obsolete historical processes. Others, like the artist Līga Spunde in the installation Hope I won’t get bored in heaven (2015), continue to critically explore the artificiality of the photographic image.

Photography that is made, not taken, has often appeared as a footnote or afterthought to the dominant narrative of the “real photography”—that subject-dominated, “documentary” variety of image-making that takes up the bulk of photography history textbooks as well as the collections of world’s leading museums. The attitude of art historians and curators as well as popular taste, however, is changing. Instagram, after all, was conceived as an image-editing app to add a nostalgic, old-school, and often “handmade” look to your too-perfect digital cell-phone snapshots. Knowing that, it feels almost ironic to see how the hashtag #nofilter is used to describe early color photographs (actually composites of three negatives) made by pioneering Russian photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky between 1909 and 1915.[4] No less ironic is calling the cartes-de-visite of the Civil War soldiers “the Instagrams of their times.”[5] Perhaps Adorno and Horkheimer’s vicious circle of “culture industry” indeed exists, and what is considered experimental and marginal once, later gets appropriated by the mass culture.

***

The Riga Photomonth exhibition Paintings and Sculptures curated by Arnis Balčus and Elīna Sproģe is on view until 30 May at the exhibition hall of National Library in Riga. It features works from artists of three different generations – Eduards Gaiķis, Valters Jānis Ezeriņš and Līga Spunde. Their experiments with photography reveal the quest for the boundaries of the medium.

The article was originally published in Riga Photomonth catalogue.

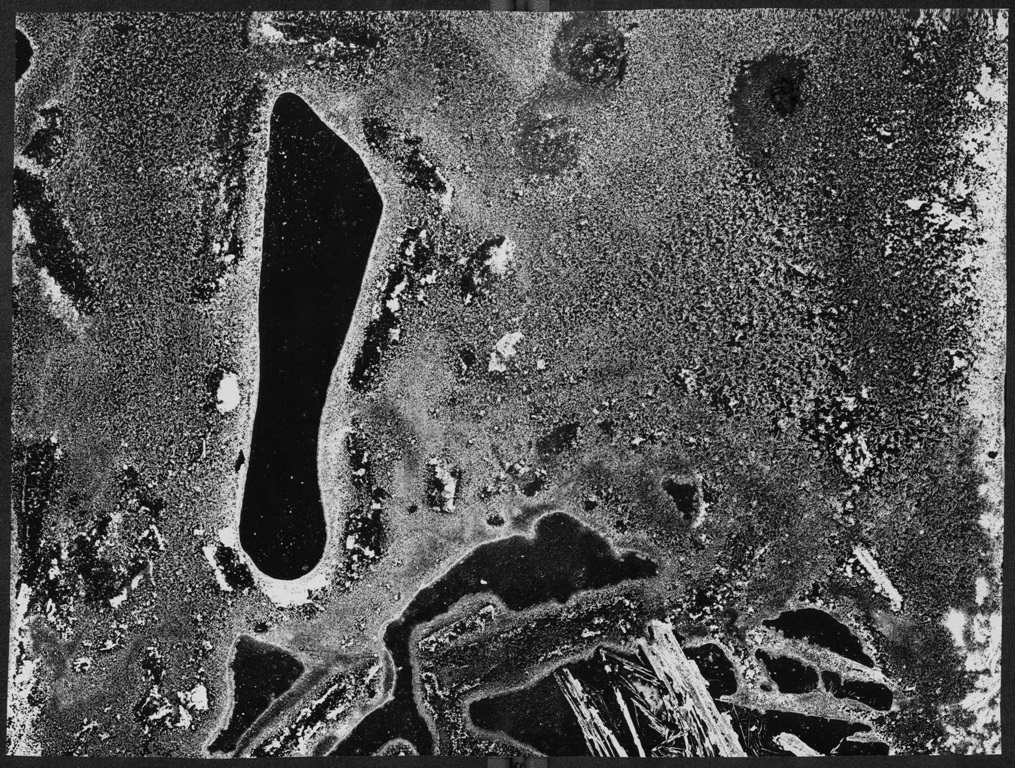

Exhibition view. Photo by Kristine Madjare

Exhibition view. Photo by Kristine Madjare

Exhibition view. Photo by Kristine Madjare

Exhibition view. Photo by Arnis Balcus

Exhibition view. Photo by Arnis Balcus

Exhibition view. Photo by Arnis Balcus

Valters Janis Ezerins. Crystallographs (1964-68)

Līga Spunde. From the series Hope I Won’t Get Bored in Heaven, 2014

Liga Spunde. Unhurtness, 2014

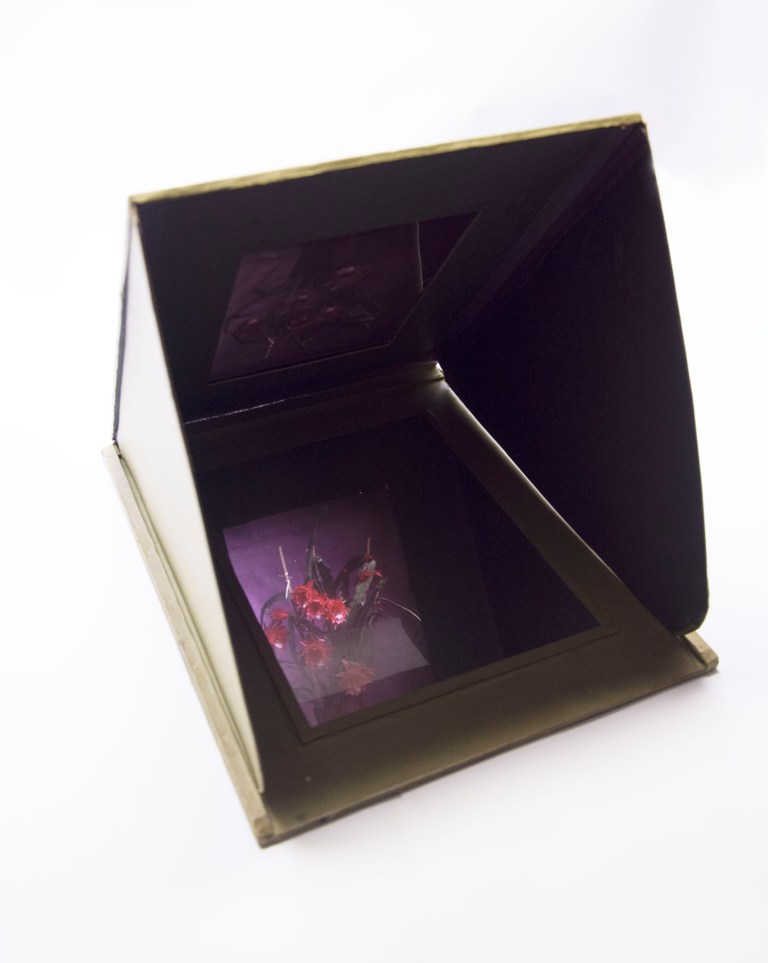

Eduards Gaiķis. Autochrome in a diascope

[1] Robert Hirsch, Transformational Imagemaking: Handmade Photography since 1960 (New York and London: Focal Press, 2014).

[2] “The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013,” The Oxford Dictionaries, November 19, 2013, available at http://blog.oxforddictionaries.com/press-releases/oxford-dictionaries-word-of-the-year-2013/.

[3] For a relevant discussion of different types of photography on Instagram, see: Lev Manovich, “Subjects and Styles in Instagram Photography” (2016; Part I available at http://manovich.net/index.php/projects/subjects-and-styles-in-instagram-photography-part-1, Part II available at http://manovich.net/index.php/projects/subjects-and-styles-in-instagram-photography-part-2).

[4] Chris Pleasance, “Who needs Instagram filters?”, Daily Mail Online, May 13, 2015, available at http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3079645/Who-needs-Instagram-filters-Beautiful-100-year-old-images-look-like-altered-actually-earliest-colour-photographs-including-antique-selfie.html.

[5] Natasha Frid, “About Last Night: Milk Gallery’s Civil War Flashback for Soul-Lit,” Milk, July 22, 2015, available at https://mi.lk/articles/4181-About-Last-Night-Milk-Gallery-s-Civil-War-Flashback-For-Soul-Lit. The article is about the exhibition “Soul-Lit Shadows: Masterpieces of Civil War Photography,” curated by Johan Kugelberg at the Milk Gallery, New York, July 22 – August 21, 2015.