Rūtenė Merk is one of the most intriguing young Lithuanian painters. Her work reveals a multitude of prevailing tensions in the field of art and beyond. One of the most interesting aspects of the artist’s practice is how, through her sensitive regard for her medium, she simultaneously elaborates on and breaks with the Lithuanian painting tradition. I hope this conversation will serve to reveal this ambivalence.

I am delighted to get the chance to conduct this interview at this specific moment, Rūtenė. Partly because I believe that your artistic practice has experienced quite a sudden shift over the last few years, which I hope can be better understood and expanded on through this conversation. And partly because, on looking back, it becomes apparent that figurative aesthetics are regaining momentum in contemporary art. After lingering on the margins for a while, figurative works have returned to the galleries, kunsthalles and museums.

While you were based in Vilnius, you occupied a rather ambiguous, even uncomfortable, position. As a painter, you were associated with Lithuanian post-conceptual artists and their core ideas. Meanwhile, among them, you were regarded as primarily a practitioner of painting. I am curious how you see this relationship then and now, especially in the light of all your collaborations, even singular, accidental ones, such as the repainting of Malevich’s piece in the context of the 12th Baltic Triennial, a series of dinners, and part of the scenario for the exhibition ‘Tap VVater’ created with Jonas Palekas, the crafting of one of the first ‘tunarolloranut’ objects conceived by Robertas Narkus, etc.

Thank you for the invitation to talk, Audrius.

Yes, I studied painting, but I found the field too shallow in Lithuania; it lacked diversity, and did not present vocal or differing positions. I did not fit into the local context of painting, since I did not agree with the masculinist culture and ideology of its authorities. I followed the agendas of the CAC, and the Tulips & Roses and Gardens galleries, because the post-conceptual art scene in Vilnius had more energy, openness and irony. But I always knew I wanted to paint, and generally to work in a studio.

For me, collaboration was a natural part of being on the contemporary art scene. The repainting of Malevich’s Sisters was an interesting challenge on the theme of the timelessness of painting. Jonas Palekas and I tried to approach the culinary arts in a conceptual and experimental way, but I didn’t incorporate painting into this practice.

I was attracted quite early on by what I would now call the semblance of a digital image. During my studies, photography and video art were still the most popular mediums in art, and various screens and the circulation of images solidified into an unavoidable part of our daily lives.

It was curious, for example, to find an entry like this on my old Tumblr: ‘Pinhole picture made from light, paper and silver vice versa digital picture found on the internet made from pixels. They both represent contrary sides of the space.’ Or this photograph, produced when I was studying in Edinburgh and trying to connect elements of impressionist style and digital image, the anachronicity of painting and the impact potential of a contemporary image.

Rūtenė Merk, Vingio parkas, Vilnius, 2012

And what is your life like in Munich? Do you still collaborate with other artists?

After moving to a new city, I began collaborating with the city itself. Having already tried out a couple of residencies, I realised that painting needs constancy and a good technical basis, which are pretty highly developed here. The city itself is not very large, but it offers quite a lot of notable shows on contemporary painting, and there is a wide network of art museums and institutions.

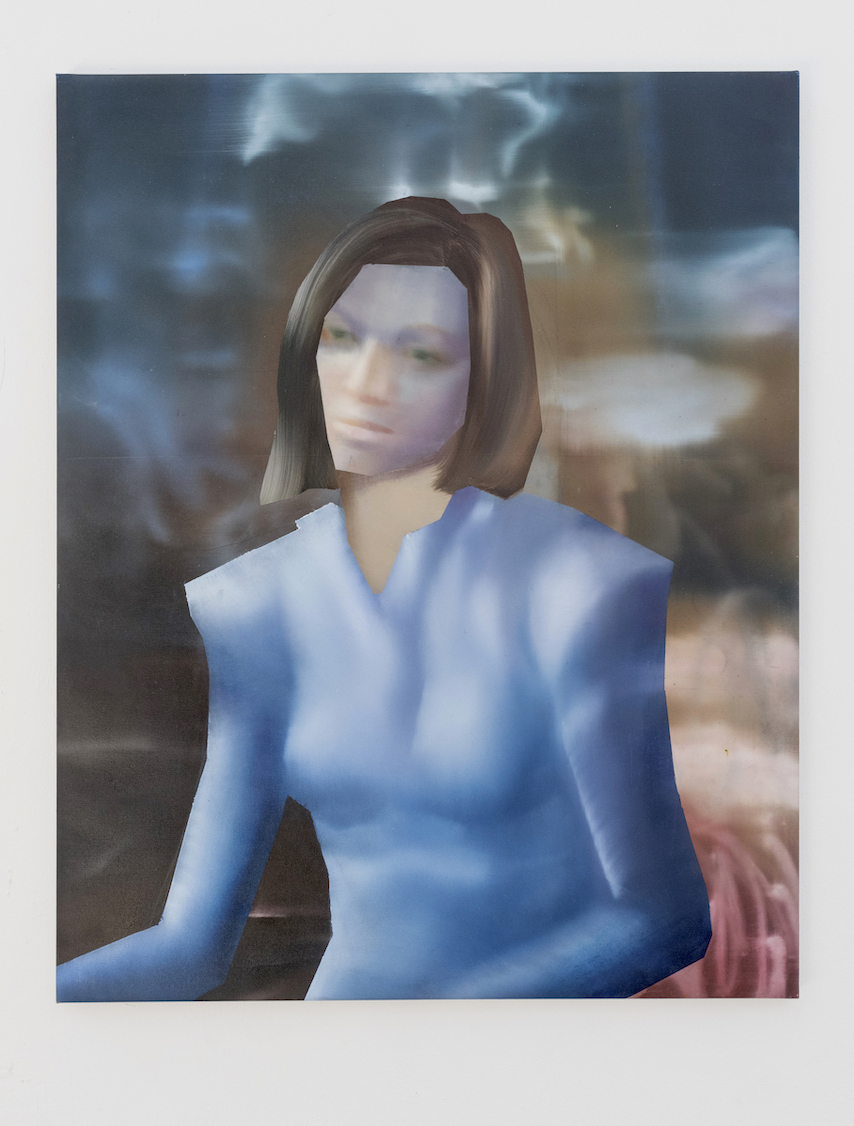

Your works from the last few years present ghostly but straightforward depictions of certain tropes, which are usually easily recognisable by their content and form: Wilson the Volleyball, Aki Ross, still-life with a crab claw and a salad leaf. Still, it seems as if the actual selection of the depicted objects, although clearly well thought out, is not of the utmost importance: appearances crystallised in the very multitude of images, able to turn into something else just as they are grasped. But there is something the chosen images share: your paintings usually depict characters or objects which, originating as fiction, attained an actual symbolic charge in popular culture, becoming ‘more real than real’, turning into simulacra of sorts. It would be interesting to find out how you choose what you depict in your paintings?

In all fairness, I choose my painting motifs slowly, and I reject a lot in the process. In spite of external and internal pressures, I am not an artist with a singular motif or a singular obsession. A large part of my works are portraits, and, for example, some of the latest ones are attempts to repaint a character I have already taken a liking to, Aki Ross from the film Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within. I would connect the Egyptian version of Michael Jackson (Remember the Time First, Remember the Time) to my earlier work David, in which I repainted an androgynous sculpture by Verrocchio depicting the young David after overpowering Goliath, the supposed model for which was the young Leonardo, who at the time was an apprentice in Verrocchio’s workshop. Both of these figures are historical, and also timeless museum objects. Avatar Aki, the Egyptian King of pop, and Wilson the volleyball were the three figures featured in both the ‘Spirits Within’ and the ‘Virtualcros’ shows.

The other inspiration for both shows was ‘Tronie’ (face), a subgenre of Dutch and Flemish painting. It spans expressive, occasionally grotesque portraits of individual types, ‘stock characters’, e.g., a beggar, a fool, an old man, a young woman, Jesus, Mary, or even faces of flowers or fruits. On the other hand, it is known that these nameless portraits usually had actual people (‘sitters’) posing for them. I looked for traces of this realness while repainting so-called ‘minor characters’ from computer games, digital avatars, which occasionally lead brutal, nameless lives (Leonda).

I’m not sure I see my characters as simulacra as described by Jean Baudrillard. I like Hans Belting’s notion of the inherently contradictory nature of the image: images make physical (bodily) absence visible by turning it into an iconic presence. Every image, even though it is unavoidably interlaced with the spectral, retains an element of reality to it. In my virtual space, a crab claw from a computer game meets a ‘real’ car or phone, and the digital avatar meets me. By calling the show ‘Spirits Within’, I wanted to refer to ‘souls’ living in various image mediums, as if they were artificial bodies.

It seems that, visually, the impression of ghostliness is evoked by the fact that your paintings are produced not so much to be looked at directly, but intended to be seen through an LCD screen, as if this mediation was presupposed in them. This liquidity of depiction made me see your works not by interpreting them positively (as in, what they are about, what is depicted, etc) but rather negatively, i.e. by examining what the images don’t reveal, what they stand in place of. Blurry coloured backgrounds and clipped figures reminiscent of computer graphics channel their replaceability, as if their position could be occupied by any other image, and their transparency, whereby an image taken out of context uncovers the ideological charges of these objects-symbols, which are almost forced on us, and indicate the conformism conditioned by seemingly innocent depictions and entrenched in contemporary culture. It is especially interesting in the context of painting, which in the popular context is probably the medium most associated with the individuality of an artist.

Your remark about an LCD screen is partly true. My paintings are not intended to be viewed solely through screens, even though that is unavoidable. I don’t paint ‘from nature’, and don’t create characters ‘in my head’. I draw from the digital image, the sources of which vary: a film still, an image ‘from the internet’, a screenshot of a computer game, a digital render, a phone snapshot, etc. The screen participates in the chain of painting as an example of an image, a tool for composition, a means of documenting the process, the memory bank of a finished painting.

The painting of a digital image on canvas, due to both the static nature of the painted image and the anachronicity of its institution – the process of working in a studio, the gravity of art history – unavoidably separates it from its digital dissemination, and slows it down. Painting is a dinosaur-like apparatus of sorting and accumulating images.

I would agree with the remarks about the liquidity and replaceability of the digital image. It is more easily disseminated, and more prone to manipulation than its precursors. I try to register that on the surface of the canvas. The sudden shift in my painting that you mentioned before is probably this expansion of form, which expresses the digital image more accurately.

But I would doubt that these new images are more transparent, or that my paintings reveal their ‘ideological charge’. Rather, they are ambiguous, cloudy and spectral, requiring a slow mode of viewing that would investigate their believability and reliability as an incredible story or an unclear testimony. I would not ask how ideology can be exposed, but how it can be chosen correctly. I think Aki Ross has a hopeful political future.

I am also interested in the relationship between artwork and commodity, and I think that, especially now in Lithuania, it is important to discuss this briefly. Despite the fact that we see works of art as self-sufficient objects, granting them the privilege of autonomy from the rest of the world, they still circulate in the economy as things among things. Even more so, the art market is probably a paradigmatic example of the speed of savage capitalism, when it is not so much the object as its value that is fetishised. On the other hand, the origin of this value lies in romantic and religious images of uniqueness and genius. I don’t think there was ever a time when this tension did not exist, but I also can’t help noticing that over the last few years it has become more problematic. A favourite example of mine is the 2016 Berlin Biennale, curated by the New York collective DIS. Despite the variety of activities that this collective engages in, it is first and foremost a fashion and lifestyle magazine. The biennial itself received a lot of often substantiated criticism regarding its falling out of touch with the locale and alienation from the art community and the city; but in my opinion, it also presented one of the symptoms of the thinning line between the fields of art and the creative industries, which is undoubtedly observed in the art market as well.

I know you’re currently working with galleries in Vienna and the USA, so I naturally want to ask how you regard the art market, whether these tensions are familiar to you, and how many possibilities you see for a young artist to participate in it?

What a difficult but interesting question!

I’m not an expert in the art market, but I think it has quite an interesting structure, simultaneously conservative and mobile. It is apparent that art possesses both a financial and a symbolic value, even though for me that does not automatically create tension.

I didn’t see the biennial curated by DIS, so it’s not easy to talk about it, but I think awareness is not a new artistic strategy for the fashion and business industries: Andy Warhol and Reena Spaulings could be examples.

Social media grant new possibilities for young galleries and young artists alike. And for me it is this constant and unavoidable overload of information and knowledge of so many good young artists being out there that creates the tension. On the other hand, networking is often overrated, and I would agree with you here, although maybe less ironically, that the value of art is partly not a matter for this world.

If so, then tell us how you became the star of a reality show in Japan!

Very unexpectedly! Probably due to hashtags like #nukadoko, #nukazuke or #koji. The Japanese producers of a show on Tokyo TV noticed my experimental cooking blog, and offered me an opportunity to familiarise myself close up with their tradition of fermenting vegetables. By the way, this great journey ended unexpectedly and symbolically in the restaurant which served as the set for ‘Lost in Translation’.

And what is your relationship with contemporary popular image culture?

This question is so absolute that I can only reply with a joke: my relationship with contemporary image culture is a friendly one.