Before an important night of talks at the British Film Institute, filmmaker Mike Figgis was entrusted with driving Jonas Mekas to the event. Accidentally making a wrong turn, the driver had no other choice but to go all the way back on Waterloo Bridge in the peak hour. Anxious about the mistake and being so late to an important event, Figgis turned to look at Mekas and, expecting to confront a concerned face, he saw instead that the filmer was recording something of great interest to him through the car window. “I am glad you made the mistake,” Mekas smiles. Accidents make for some of the most beautiful moments in his oeuvre. Accidentally or not, the Mekas fever that raged throughout last December – when hardly a day passed without a story on a Mekas retrospective or an exhibition in international press – involved some highly unexpected personalities like Pamela Anderson, who shared an extract from Walden with her 0.5 million Facebook fans. Therefore the following conversation with Jonas Mekas ponders on differences between accident and experiment, between documentary and diary, and on the beginnings of everything.

The Pompidou retrospective opened with images shot in 1949-1950 Brooklyn, Williamsburg. These images mark the beginnings of you as a filmer. What originally drove you to record life and sights around yourself, what were you most interested in capturing at the time?

My brother Adolfas and I acquired our first movie camera, Bolex, within months of arriving in New York. We started filming for no apparent reason, just to learn more about the new “tool” and see what we could do with it. At the time, we lived on Lorimer Street in Williambsurg, Brooklyn. If I’m correct, the first shot we took was of a tree that was growing on the street outside our house. We started by filming our hands, one another, and progressively our horizon grew – into the streets, parks. In a word, all started with us trying to master a newly-acquired cinema apparatus.

Where and to whom would you screen your first films?

We only showed materials from the first years to our friends. We had a projector, so we could show films at our home. The circle of friends later expanded – we could hold screenings at our friends’. But I would not show my films publicly for almost ten years, until I finished Guns of the Trees (1961). So for a decade, I just filmed and wrote scripts that I’d send to Hollywood and have returned back to me. We would often go to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) with Adolfas. They’d have a new screening of movie classics almost every day. It was a period of learning film history. At the time, there were several experimental filmmaking clubs in New York, we kept an eye on those, too. We met quite a few young people who were interested in cinema and filmmaking there. We’d spend nights at cafés and pubs, discussing what we’d seen. Sometime around 1951, my brother Adolfas got drafted and I started filming Lithuanian immigrants in Brooklyn and other places I travelled to: Boston, Philadelphia, etc.

In spring 1953, a few of my friends and I opened Gallery East on Avenue A and Houston. It was the first gallery in Lower New York. We decided we should exhibit not just artworks, but also films – that was where we started screening avant-garde cinema.

It seems that at some point in your life you would have gladly chosen a career in Hollywood. When was the turning point that made you realize independent/avant-garde cinema was more interesting to you?

The more I saw of it, the more important the avant-garde branch of cinema became to me. Truth be told, before coming to New York, I hadn’t seen any of the French and German cinema of the 20s and 30s, I had no idea there was an alternative. The more I saw of historic and contemporary independent cinema in cinema clubs and MoMa, the more it attracted me. Until around 1960, I was a schizophrenic, torn between the familiar mainstream cinema and the newly-discovered non-commercial cinema. My first film Guns of the Trees was made without a detailed script and largely improvised, even though some of the dialogue was scripted and actors had to act it out. This shows how I was balancing between two distinct filmmaking modes. But then, as I was looking at the previous footage I had done, I saw that it was a film diary of sorts, it reflected my entire life, my friends. Much of that footage was later used in Lost, Lost, Lost (1976), the first section of which depicts lives of Lithuanian emigrants. I noticed I was drifting away from the “fabula-based” and towards poetic cinema, taking, above all, the form of the diary. It should not, however, be confused with documentary cinema that often employs a script and uses filmed footage to illustrate it. Whereas I simply filmed life. I made some sketchy notes before filming the lives of Lithuanian émigrés, but that could hardly be called scripting. I never knew what would happen in front of my camera.

Still, you won a documentary award at Venice Film Festival for The Brig (1964). Would you agree that some of your films could be called documentaries?

In my view, the period of documentary cinema ended sometime in the 60s, before Cinéma vérité, even earlier. Documentary film as a genre was very popular between 1935 and 1950 in England and the US. The Cinéma vérité period saw a change in technology – there came lighter, less bulky cameras, better sound recording equipment. One did not require a large crew, you could go out and film with a friend. This is how Cinéma véritéstarted – filming on location, not necessarily in a studio, without artificial lighting. Even though scripts got shorter and no one would adhere to them so pedantically, there was still some planning involved. And still, even this much looser form of filmmaking cannot be compared with filmic diary, which cannot have any scripts at all, since you cannot know what will happen the next moment. Television, too, had much to do with cinema breaking free of the script.

I would not agree to be called a documentary filmmaker. I think that people who call me that do not understand my cinema, what I do. Filmic diary, too, is a mode of documenting time, but it is a personal form of filmmaking and when I’m doing it, I do not have a goal of documenting anything. When it comes to Andy Warhol, for instance, his footage is now an important record of the period, but it is rather a small window into his private life than an official document. With time, the result does become some sort of documentation, but when I was shooting, I was not documenting – simply reacting to the environment, people, friends. Why – I do not know. I walk through life filming and do not even know why I do it. I am not a documentary filmmaker, I am a diarist.

BFI season curator Mark Webber does not like to call films ‘experimental.’ He thinks this is disparaging to filmmakers – as if they did not know what they did. What do you make of the term?

I also hate it, I might have been the first one to criticize it. In fact, none of us are experimenting, it was the press that came up with that term. Scientists might be experimenting, while artists usually go straight to the point. Sure, there is a factor of chance, accident, but when we try out one way of doing things or another, it is not experimenting. So forget this word, call our films avant-garde, not experimental.

Few in Lithuania know that Jackie Kennedy Onassis wanted you to do a biopic about her. Why did she want to entrust the task to you?

She liked my style of filming and she trusted me. She did not want a team from commercial TV doing her biography – she wished for something more private, personal. She loved my film Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1972). She showed the movie to her family and friends on Mother’s day. She also liked Walden.

I had already shot some footage for the biopic, but had to stop because certain people from commercial TV started poking in and asking Jackie who I was, why the project was given to me and not to them. And since those people were her family friends, I decided not to complicate her life and relations with influential TV channels – I suggested pushing back the project to some later date. Her biographers later wrote that shooting was discontinued due to finances, but it wasn’t so.

Your new film “Outtakes From the Life of a Happy Man” (2012), which is being screened at the Serpentine Gallery, constructs its narrative by editing together new video footage and archive 16mm film. What have you discovered while working on these two distinct formats and editing the film?

When I started editing the footage, which, for various reasons, hadn’t made it into my previous films, I decided I had to record the process and use some of it in the film. I was going for some sort of Brechtian alienation effect (Verfremmdungseffekt), when they remove the reality illusion and show the viewer that theatre is just theatre. Likewise, I do not hide that I’m editing, that this is a film, you can see me working. The only way to record the process is videography.

By the way, ever since the 1960s and 70s, I wanted to make a film out of letters sent to me by a fifteen-year-old. These were letter-diaries – the girl, Diane, wrote about herself, her life. I never made this movie and when I was editing this one, I remembered I had preserved extracts from those letters and even a sketchy script called The Film I Never Shot. So all the text in Outtakes are extracts from her letters.

You’ve stressed on numerous occasions that many of your initiatives happened from a necessity – when there was no film magazine in New York or a movie theatre screening avant-garde films. Over the years, the situation has changed radically. What needs do you see today?

Yes, back in 1953, I started screening films only because I had seen and liked some of them, while my friends hadn’t seen them and there was no place where they could. There was no other choice, the only way to show certain films to my friends so we could discuss them later was to screen them myself. The Film-Makers’ Cooperative was also a necessity, as was Film Culture. There was no other magazine where we could share our thoughts about film – so we had no other choice but to start one of our own. Well, there was a film magazine at California University, but it would come out once a year or two and it focused mostly on mainstream cinema. And in Film Culture, we wrote on both mainstream and non-commercial cinema, we treated all strands of filmmaking equally.

Now, the biggest need for cinema – movies on film – is to be preserved. Either UNESCO, or culture ministries in all the countries that used to have cinema on film should set up film laboratories so that everything that has been created over the last 120 years does not disappear. What would happen if we lost the 120 years of documentation? So I think that preservation of film history is the most urgent need. Just like we guard all other artworks from past centuries, we should preserve film.

The conversation originally in Lithuanian on Artnews.lt

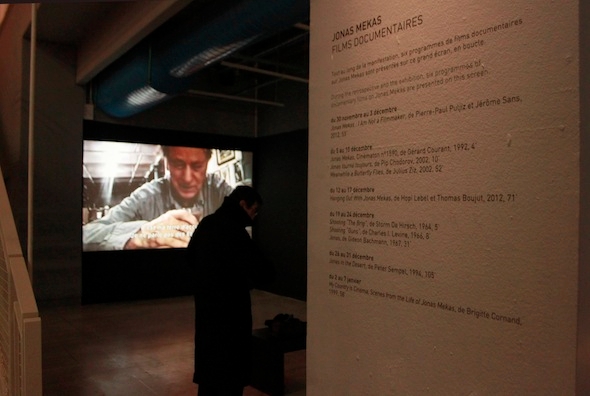

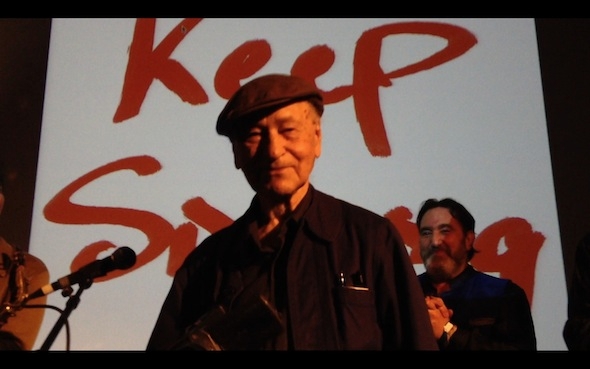

Moments from „Jonas Mekas and Friends“ (2012.12.12 Serpentine gallery, London):

Photographs by Jonas Lozoraitis and Justė Jonutytė