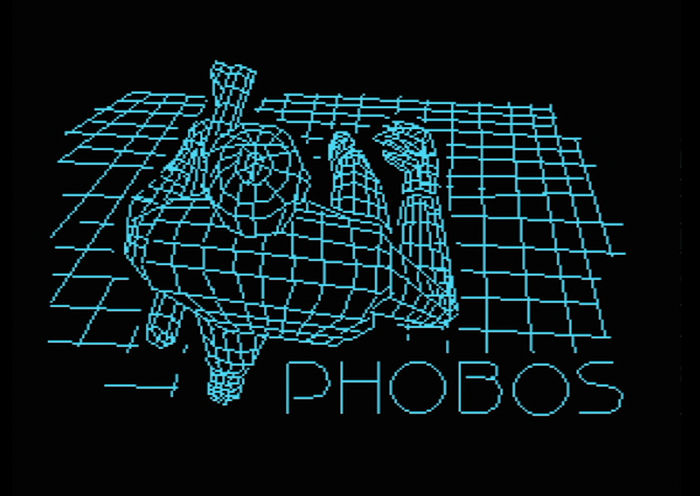

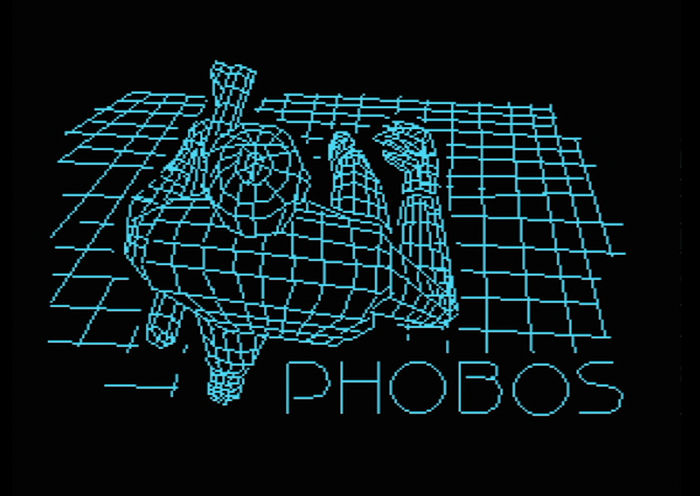

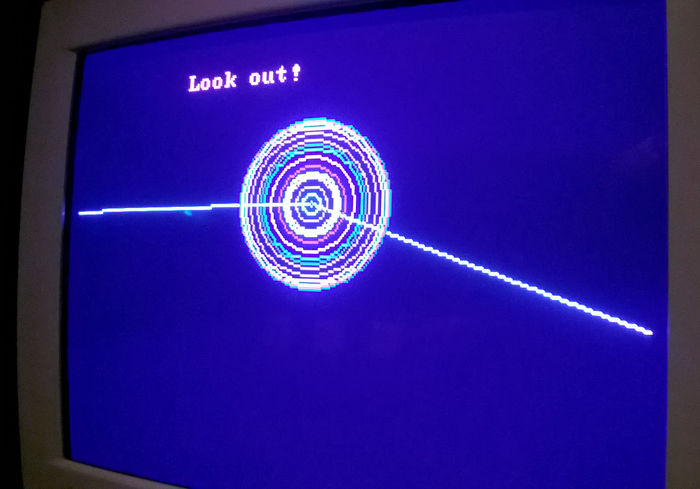

AttackerSoft (Markus Klesman, Oleg Maskhov, Raul Keller), Phobos. 1990, MSX game

Historical review and discussion of the exhibition RAM. Early Estonian Computer Art at Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn.

Since Baltic media art emerged in the late 80s, I have been following its changes. You can be sure that most changes in art come from the result of changes in technology, political systems and economic opportunities. The effect of perestroika and how Estonians gained their freedom through the “singing revolution”, which brought a bloodless change of power, is well known. During this period, when Western art and new technologies entered post-Soviet society, video art was the most radical achievement of technological art. The audiovisual context towards the end of the 80s was a TV-landscape with only four channels in Estonia (two Russian, one Estonian, and Finnish). Only Finnish television offered a window into another part of Europe. Video art was considered crazy and mind-blowing, and there was a strong belief that the more people got to see this kind of art, the more things would change.

In 1990, a few Estonian students, with personal invitations from family friends, were able to study in Helsinki at the Fine Arts Academy where Nan Hoover was teaching video art. Student exchanges between the Soviet Union and Finland did not yet exist. When the students returned, the dean of their arts academy looked upon them with contempt, asking whether they had studied television when they were out there. At that time, anything connected with the screen was considered dirty and very far from being art.

Nevertheless, the beginning of the 90s was a period of rapid change. French-Baltic video art festivals became an important step forward. The first event of this kind was a French-Latvian video art festival held in Riga in 1990, with the last event held there in 1997. In the year after that, the French-Baltic-Nordic Video and New Media Festival took place in Tallinn under the subtitle “offline@online”. And again, in the following years of 1999 and 2000, more festivals under this subtitle were held in Tallinn and Pärnu.

The digital age arrived with the international conference Interstanding – Understanding Interactivity, held in 1995 in Tallinn, organised by Sirje Helme, Ando Keskküla and the Soros Centre for Contemporary Art. The event brought together a distinguished collection of artists, theorists, activists and gurus who would grow to become influential over the subsequent decades of digital art and new media theory: Geert Lovink, Richard Barbrook, Heath Bunting, Erkki Huhtamo, Eric Kluitenberg and many others. Co-organising the ISEA in 2004, which took place in Helsinki and Tallinn, was the Soros Centre for Contemporary Art’s finest hour.

Since 1996, the Art + Communication festival and conference in Riga has been organised by Rasa Smite and Raitis Smits. This event, along with other international initiatives organised subsequently by RIXC (The Centre for New Media Culture), have become the most enduring Media-Art forums in the Baltics. RIXC have also produced other high-profile international events like Media Art Histories (2013), the conference RENEWABLE FUTURES: Transformative Potential of Art in the Age of Post-Media (2015),[1] and the RIXC Art and Science Festival (2015)[2] which replaced the former Art+Communication festival.

Rasa Smite and Raitis Smits are themselves active as artists with projects such as Biotricity. Bacteria battery (2012 – ongoing), Talk to me. Exploring human-plant communication (2011 – 2013), and Pound Battery. A Poetics of Green Energy (2014 – ongoing).[3] At the same time, they also teach in universities. Rasa Smite is an assistant professor and leader of MPLab at Liepaja University. In 2002, they were both nominated for the World Technology Awards in the “arts” category. As a team, they regularly publish their Acoustic Space series of which twelve editions have already been produced.

In looking for an outstanding project by Baltic artists, the MILK project by Ieva Auzina and Esther Polak should be mentioned.[4] Their piece won the coveted “Golden Nica Award” at the 2005 Prix Ars Electronica for Interactive Art. Also worthy of mention is the exhibition Gateways: Art and Networked Culture curated by Sabine Himmelsbach (Germany) at Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn, in 2011. The exhibition introduced a younger generation of artists whose work dealt with the changing conditions of a networked world – a world increasingly transmitted through media. Sabine Himmelsbach stated that, “Through their use of electronic networks and mobile technologies, the artists encourage[d] the public to participate actively and transport new experiences in perception.”[5] Numerous Baltic artists participated in this exhibition: Karel Koplimets & Ivar Veermäe, RIXC (Rasa Smite, Raitis Smits, Martins Ratniks), Anna Trapenciere, You Must Relax (Riin Rõõs and Eve Arpo) and Timo Toots. Timo Toots’ subsequent career has been outstanding. He was also distinguished with receiving the prestigious “Golden Nica Award” for Interactive Art for his project Memopol-2 in 2012.[6] The same project was later shown at the Museum of Communication, Frankfurt, (2013) and Edith-Russ-Haus, Oldenburg (2013), Germany.

The Tallinn-based group You Must Relax (Riin Rõõs, Eve Arpo)[7] began their activities in 2007 with A Day Without the Mobile Phone, an “action in public space” which allowed visitors to give away their mobile phone for 24 hours. The project generated extraordinary media attention and was, to a certain extent, the perfect media artwork in that it was public art, a happening, a sculpture and a telecommunicative project. It later went on to show in Canada, Germany and Brazil. The group continued their experiments based on recycled mobile phones in their project Musical Study of Mobile Phones, which was presented at Leigo Lake Music Festival and the Estonian Concert Hall (2009). The latter of these venues was, undoubtedly, the most prestigious location in Estonia. You Must Relax helped prove and make it possible for “marginal” media art to attract attention among the economic and political elite.

As my focus is mostly on Estonia with regard to the practical media landscape, it is important to highlight Timo Toots, who is currently designing media-based exhibition displays for the Estonian National Museum (ENM). ENM is a spectacular new building which will be opened this autumn in Tartu. The museum is not only dedicated to the history, life and traditions of the Estonian people, but also to recording and presenting the cultures and histories of other Finno-Ugric people and minorities in Estonia. Some of its exhibited material will be digital. Toots is also working on the next version of Memopol, although its final shape and place of exhibition has not yet been decided.

I must also mention the successful work of Varvara Guljajeva and Mar Canet[8], an Estonian-Spanish couple who have been actively collaborating since 2008. They have received prizes such as the Google DevArt award, the third prize at the FabAwards and have been mentioned as being among the “6 couples who are shaping contemporary design”.[9] After years of working in residencies, they settled down in Tallinn and opened a studio in the ARS house for their artistic productions. They facilitate workshops on Arduino and 3D printing, and have initiated “ARS Maker Tuesdays”, a new format which they describe as “an open learning, exploring, discovering, making, sharing, and socialising event, which aims to introduce contemporary creators’ tools and create a place for an on-going discussion.”[10] In this respect, Varvara and Mar are initiators and community builders. Where previously there were no possibilities for technological artists to meet and collaborate, these meetings hosted by Varvara and Mar are revolutionary in bringing together established and young artists, who can drop in and communicate, with other like-minded individuals.

Digital art education

I want to form a separate topic centred on education around digital and media art. I will mostly discuss the Estonian situation, though it is worth mentioning the BA and MA programmes in the department of Photography and Media Arts of other countries, and Vilnius Academy of Arts. Their stated goal is “to educate researchers capable of artistic research in the field of contemporary art, and realise a creative project using the most advanced media.” For that matter, The New Media Art programme at Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas[11] and the MPLab at Liepaja University, who also share similar aims and objectives, are also worth mentioning.[12]

There is a predominantly pragmatic approach at Tartu Art College where students rarely graduate with artworks.[13] The Chair of New Media at the Estonian Academy of Arts is currently led by sound artist Raul Keller, and focuses on more experimental contemporary media projects. The Chair became the successor of the previous E-Media Centre which was established in 1994.

Crossmedia[14] and Digital Learning Games[15] are two relatively new study programmes at Tallinn University which could be described as New-Media based. On the whole, their approach is practical, similar to the new programme of interaction design at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

The major difference between the various educational programmes is that there are technological education programmes oriented toward the art world and others that offer a pragmatic design-world approach. However, the ambition to educate practical multimedia designers was already present in the mid 90s. At the time, media art’s position within the wider art world was rather vague. Now all fields have developed into two general directions: Media Art and Media Design—the latter, taken to include interactive design which could have minimal artistic ambitions. One might also include here the digital film approach—although most contemporary film education is now carried out via a digital platform.

As film is a money-intensive activity, an expectation to connect it with business often arises, which is where Cross-media and Transmedia grew out of. Despite these newly affiliated forms being rather tightly connected with the commercial world, there are undoubtedly interesting cultural developments born out of them. By that, I do not mean to say that other projects originating in the art world are created without expenses when there are also funds and sponsors providing financial support for artistic production. However, I would like to emphasise the distinction between the artistic and the pragmatic or commercial approaches and fields. Few projects seem to fit into either approach or field simultaneously. As a result of this, things can seem unclear with those who create techno-art objects for the art world running the risk of them being misunderstood by both sets of audiences.

The Viljandi Culture Academy of Tartu University deserves a mention for including its speciality in “theatre technical arts” within their performing arts department. The specific aim of this programme has been to teach the use of media technology within theatre, as nowadays, more and more contemporary theatrical artists seem to be integrating or separating digital technology from the stage narrative.

Erik Alalooga is a notable example of a technological performer from Tallinn, persistently expanding his field. He led the interdisciplinary art department at the Academy of Arts for many years, despite its recent closure. Alalooga’s speciality is in technological performances, organising them mostly with students who take part in his courses at the Academy of Art or at Viljandi Culture Academy. His techno-theatre and performances with self-made musical instruments frequently appear within Tallinn’s galleries and performance spaces. Recently, he opened Supersonicum, a sound art and experimental music gallery in Viljandi.

As I mentioned earlier, with regard to media education and digital technology-based visual art in general, I believe there to be a split dichotomy between those whose practices end up seeking non-commercial avenues within the art world, and those whose practices contribute to a more pragmatic means. I would define film education as being rather practical and applied, with an outcome situated in the conventional cinema environment. Accompanying peripheral fields like Cross-media tend to be for the marketing of the cinematic product which can help individuals learn to bring media to a wider audience. All in all, in successful cases, these fields have helped create a vital environment for young professionals with diverse abilities to achieve greater potential than what might have been possible for them, if their interests remained invested in the non-commercial scene of the Baltic art world.

What is happening in the world of media art correlates with what is happening in the historical and theoretical research fields of media culture and media archaeology. By this, I am referring to a specific view of new technologies, non-material art and digital-born art that is based on an art-historical approach.

Here, I want to mention Rhizope: Art & Science – Hybrid Art and Interdisciplinary Research (2014) an exhibition and event held at the Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design, curated by Piibe Piirma[16] which attempted to answer various questions. What is ArtScience? How should we see cross-disciplinary and trans-disciplinary phenomena? How does new knowledge come about through hybrid forms of cooperation between art and science? Other questions related to contemporary bio art and ArtScience were also posed. Participants included Simon Penny, Dmitry Bulatov, Reiner Maria Matysik, Martin Howse, Sara Robinson, Lennart Lennuk and Ulrich Gehmann among others. The objective of the conference and exhibition was to highlight the most important areas where fine art, design, architecture and other fields of art intertwined with science. Subsequently, in 2015, Piibe Piirma defended her PhD thesis on HYBRID PRACTICES. Art and Science in Artistic Research which was based around this exhibition and conference in addition to her own hybrid artworks. It is also worth noting that that one of Piirma’s projects was sent into space with the Estonian satellite Estcube.

Piirma is a great example demonstrating the direction in which media artists and researchers are heading at the moment. Her career highlights the fact that opportunities in the field of media art exist where one is able to realise research, doctoral theses and exhibition projects simultaneously.”

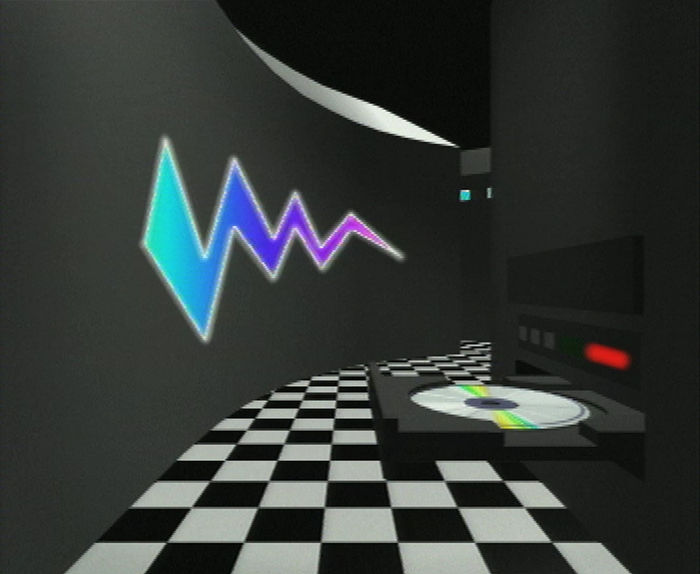

The FARM / BlueMoon Software (Jaan Tallinn, Ahti Heinla, Priit Kasesalu, Juhan Soomets, Kaspar P. Loit, Ott M. Aaloe), Computer game Roketz. 1995

“RAM. Early Estonian Computer Art”

RAM: Early Estonian Computer Art at the Art Museum Kumu in Tallinn, taking place from 17.02. – 04.09.2016, is an exhibition which presents us with another opportunity to discuss the history of digital art.[17] It is undoubtedly held in one of the most prestigious exhibition venues in Estonia, providing a thoroughly selected compilation of digital art from the late 80s to the early 90s.

Tuuli Lepik has been dealing with new technologies since the 90s and defended her MA thesis in 2004 with the title END IF or An Overview of Early Estonian Computer Art. In my humble opinion, she is the author of one of the most beautiful multimedia artworks made in Estonia in 2000 called Artificial Intelligence. This project led me to want to talk about an area of media art conservation which is currently of great interest — the preservation of digital-born projects. Whilst a lot of creative talent and beautiful artworks have been contributed to this field, they are gradually fading, becoming less available as programmes and computer platforms become obsolete or evolve.

A British artist who has been responding to this question of obsolescence in Estonian media art is Chris Hales, who teaches at several institutions in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Finland. Hales has curated a considerable amount of digital artworks that could be categorised as “interactive cinema”. Despite his earlier days being full of witty creative energy spent expanding the possibilities of interactive storytelling, Hales observed the unfortunate decline and gradual fading of this field as it shifted further towards the periphery. Nevertheless, he has continued to react flexibly to the technological changes. He has adapted his interactive narrative course to teach a variety of up-to-date software and hardware platforms, recently incorporating commercially-available headsets used to measure scientific data from brainwaves.

Tuuli Lepik’s exhibition similarly highlights the obsolescence and progression of computers by presenting interesting digital artefacts that are clearly outdated from the late 80s to the early 90s. Her exhibition illuminates the way in which animations and multimedia-like programmes were created back then. The exhibition makes it possible to see how computer graphics were produced, how scientific data was generated and visualised in university computer centres, and how the Yamaha MSX was used in schools for game development, amongst many other pioneering insights.

Despite whatever aesthetic evaluations these productions could be assigned to, it is possible to place all of these into a “history of computer art”. What is also clear is that these projects all vary in innovation. They all have different qualities which range from being very simple, almost naive projects, to works containing universally recognised visual and aesthetic qualities. The exhibition reveals the constraints of that era, showing how the “visual quality” was, of course, dependent on the limitations of the software and hardware of its day. But in spite of this, numerous examples remain fresh and are still of interest today.

Looking back at the early days of digital art and comparing them with the recent fever for technological start-ups, it is possible to begin forming some conclusions. At the beginning of the 90s, several games including Kosmonaut, SkyRoads and ROKETZ were designed by BlueMoon Software. Jaan Tallinn, Ahti Heinla and Priit Kasesalu were programmers who later went on to develop Skype, and also became known as the designers of the early file sharing software Kazaa. Nowadays they are developing delivery bots at Starship Technologies.[18] Though Skype was bought by Microsoft and belongs to the everyday life of “netizens”, what remains of interest and is important to demonstrate is the influence certain designers and programmers of the early Estonian gaming industry had on our everyday global communication.

During the 90s and the 00s, software designers and artists were more free to form connections and collaborations, working on all different types of products. Nowadays, they could not be more separate having shifted into discrete boxes. Those with serious IT and technical competency skills seem less concerned with anything other than entrepreneurship.

To conclude, it is clear that creative practices based on digital technology have spread practically everywhere, from visual art into applied fields. The world encounters digital technology in the theatre, at the cinema, in numerous scientific fields and occasionally in galleries presenting interdisciplinary exhibitions and projects. Where once it was possible to identify specific groups of avant-garde innovators appropriating new technologies, these days it has become harder to distinguish them in our world where digital technology has become a cross-cultural constant.

Amiga 1200, assembled by Retrocomputing Estonia, Juhan Soomets and Ott M. Aaloe. The FARM (Juhan Soomets, Ott M. Aaloe, Kristjan Paemurru, Kaspar P. Loit) Computer game Roketz. 1994–1996

Rauno Remme, Wanna play? 1992 (The programme was written in Basic to parody computer games; there is actually no possibility of winning.)

Hillar Uudevald, Noli turbare circulos meos! 1993

Renee Kelomees, Geom I. 1994, Amiga Deluxe Paint, Music: Renee Kelomees

AttackerSoft (Markus Klesman, Raul Keller, Kaspar P. Loit), Adventurer. King of England. 1990, MSX game

Marko Kekišev, Kalle Toompere, Advertisement for Amerest. 1990–1991, Olav Osolin’s private collection

Photo: Exibition RAM: Early Estonian Computer Art at the Art Museum Kumu, Tallinn.

[1] http://rixc.org/en/conference/

[2] http://rixc.org/en/festival/

[3] http://rixc.org/en/projects/; http://smitesmits.com

[4] http://milkproject.net

[5] http://www.goethe.de/ins/ee/prj/gtw/ueb/enindex.htm

[6] http://prix2012.aec.at/prixwinner/5563/

[7] http://youmustrelax.com

[8] http://www.varvarag.info/

[9] https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-6-couples-who-are-shaping-contemporary-design

[10] https://www.facebook.com/events/1628444280745783/

[11] http://www.menufakultetas.vdu.lt/studies

[12] http://mplab.lv

[13] http://artcol.ee/en/departments/media-and-advertisement-design

[14] http://www.tlu.ee/en/Baltic-Film-Media-Arts-and-Communication-School/Admissions/Crossmedia-Production

[15] http://www.tlu.ee/en/studies/Degree-Programmes/Masters–programmes/Digital-Learning-Games

[16] http://www.piibepiirma.com

[17] http://kumu.ekm.ee/en/syndmus/ram-early-estonian-computer-art/

[18] https://www.starship.xyz