Among us all there are feeders and there are eaters. Most of us are eaters – but only some of us are feeders. In Oslo, at the Migrating Art Academies Food / Biotechnologies / NeoColonialism workshop in May 2014, most of us were feeders as well as eaters, which, given that we lived and worked together for the entire time, boded well for the week.

“If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world.” – JRR Tolkein

Food is, primarily, fuel. Around the back of the Central Stasjon in Oslo, the Fattighuset, the Poverty House, provides food to those who cannot afford Oslo’s high prices, donated by the city’s supermarkets. The recently arrived, the recently evicted and the recently redundant are all welcome without prejudice, with no demand for papers or permission, and the queue for food parcels on every Friday is many hundreds strong.

Food is also love – a connector to our families and desire to nurture and grow. On the first full day of our workshop we visited a seemingly abandoned spot in Herligheten, within sight of the roof of the opera house and overlooked by a busy arterial road that services the city. People have taken over this waste ground to grow their salads and vegetables in raised garden allotments. When we visited it was cold, grey and raining quite hard, yet there was a sole Asian lady tending her radishes in the wind and rain as if they were growing gold. The plastic sheeting she used as a cloche battered in the icy wind as she showed us her young seedlings.

Food is, yet again, a signifier for sophistication, and we can’t help ourselves but to make our judgments upon the desired foods of others. Upmarket Maldon salt from Essex in England had a firm place in the well-appointed kitchen in our middle-class Oslo family house, yet there was no roasting tray to be found and few saucepans. Five tubes of squeezy cod roe lived alongside a bewildering array of Scandinavian condiments in the American-style fridge but the spread for bread was margarine, not butter.

Two cornerstone projects in the MigAA Food workshop in Oslo examined our relationships to food and the identities it can appear to bestow on us – or should that be the identities that we bestow on it?

Persefoni Myrtsou (born and raised in Greece, living and working in Berlin and about to marry a Turkish man and spend some of her time in Istanbul) cooked moussaka for the workshop and for visitors and as she did, she talked about the ingredients, their origins and histories, such as the tomato, which is now a staple of the Greek kitchen but was introduced to Europe in the 1600s by the Spanish conquistadors who’d brought it from Mexico where it had been domesticated after originating in the Andes mountains a very long time before that.

It’s easy to think that moussaka confirms the assumptions we make about it, that it’s very Greek and very traditional, but, Persefoni explained, its modern Greek form was invented by an early 20th Century Greek chef and ideologue, Nicholas Tselementes who, as part of a new Greek modernism, determined to rid Greek cuisine of its long-standing Turkish, Roman and other influences. He sought to “purify” Greek cooking, through the introduction of French cooking methods such as Bechamel sauce, which were much more sophisticated than the peasant foods of old, and he became the darling and kitchen-essential of the Greek bourgeoisie.

Moussaka, as Persefoni pointed out, isn’t even a word of Greek origin – it’s probably Arabic, and different versions of it exist in every country and region across the near and middle East, like hummus and falafel, two other common topics of Mediterranean culinary dispute. Yet if you asked anyone what they consider to be the most famous Greek dish, there’s a good chance they’d say moussaka, such was Tselementes’ success in “cleansing” Greek cuisine of Ottoman influences, via French technique.

“There are people in the world so hungry, that God cannot appear to them except in the form of bread.” – Mahatma Gandhi

Diaz Juan Pablo (born and raised in Columbia, living and working in Berlin) cooked tamales. He’d never cooked tamales before but his mother did, and Juan described to the workshop and to visitors how tamales are very much a comfort food, a dish to be made and shared on special occasions. Like moussaka, except that tamales go back to the pre-Columbian era, a portable food stuff, originally carried and eaten by warring Aztec, Mayan and Incan armies, prepared by the Aztec women they took along with them and now loved by Hispanic people across the Americas. Juan explained that because tamales are eaten across many different peoples, countries and regions, each has their own local ingredients, not least for the masa, the dough made from cornmeal that holds the fillings in place, which in turn, is held together with a wrap made of any readily available, large leaf.

Using cornmeal and banana leaves he found in an Oslo Oriental supermarket, Juan explained that for the last 20 years, nine out of 10 corn crops are now genetically modified, and usually they’re mono-cultured, that is, they’re all the same breed of corn. In 2008 alone, Monsanto’s triple stack corn was planted on 32 million US acres. But it wasn’t always this way. Corn, like the tomato, was first domesticated in Mexico and was taken down to the more southern Americas where indigenous varieties began to grow, such as Black Aztec Corn, Bloody Butcher Corn, Brown Sugar Popcorn, Cancho Blancho, Country Gentlemen, and Dakota Black((http://www.treehugger.com/green-food/6000-year-old-peruvian-popcorn-reminds-us-how-new-gmo-corn-really-is.html – accessed 20/5/2014)). Genetic modification is a controversial development for a main, subsistence crop such as maize. It has been illegal to grow GM corn in Mexico since 1998((http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2013-10-30/brazil-says-yes-to-genetically-modified-foods-dot-mexico-says-no – accessed 20/5/2014)) yet in Brazil, GM beans are being embraced wholeheartedly for their national crops, not least to eliminate the hazards caused by local viruses((ibid – accessed 20/5/2014)). It is likely to remain controversial in the Americas, not just economically but culturally and philosophically, for as long as strong national and regional feelings remain attached to these basic and fundamental ingredients.

Food policy itself remains controversial. We throw away 30 – 40 percent of the food we produce and yet nearly one billion people live in near starvation((http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/may/26/feeding-frenzy-hungry-man-rayner-review – accessed 20/5/2014)). Panic in the commodities markets in 2008 and 2010/11 forced food prices up by 30 percent((ibid – accessed 20/5/2014)). In other recent years, failed harvests or poor weather have rocketed up prices of tinned tomatoes, coffee, chocolate and most recently there was a threat to the cost of the humble lentils and rice. When prices rise, they rarely go down afterwards unless there are important commercial reasons for the retailers to reduce and Kim Hachmann and Steffi Simmen (Form Future collective) presented a manifesto for local food production outside of big business in the video piece they made on site in Oslo.

The current vogue for local produce is preceded by the story told by Matthias Roth’s moving image of the cucumber, a common fruit in Cold War Eastern Germany, morphing backwards and forwards with a “morning glory” of tumescence into a banana, a fruit so unattainable and so desired by East Germans that they broke down the Berlin wall to avail themselves of them in the West Berlin shops, refusing to believe that there would be more tomorrow and the day after((http://zeenews.india.com/home/when-bananas-brought-down-the-berlin-wall_577051.html – accessed 20/5/2014)).

Our relationships with the food we rely on or that we love can be odd, when seen by the standards of others. Amber Ava (raised in London, UK and studying in Bergen, Norway) cooks for an office of professionals to make her rent and explained how they are delighted to be fed middle-eastern lunches, for example, but would not be happy with, say, English comfort foods such as cauliflower cheese. Amber offered recipe cards for the bread and the cheese we’d made under Brian Degger’s guidance during the course of our workshop, along with tokens of exchange which could be traded for samples of the food and drink on offer during our public event in the gallery. To earn these, guests were asked to write a note, a story or a recipe for a food that is meaningful to them, such as their childhood comfort food to their student survival food to the food they’d learned to love while travelling or on holiday.

Lina Rukevičiūtė and Mindaugas Gapševičius experimented with bio-techologies to explore directions of travel for organisms with chemical compounds – Miga by finding ways to generate new salt crystals, Lina by setting an apple on a road to mummification.

“Fermentation may have been a greater discovery than fire.” – David Rains Wallace

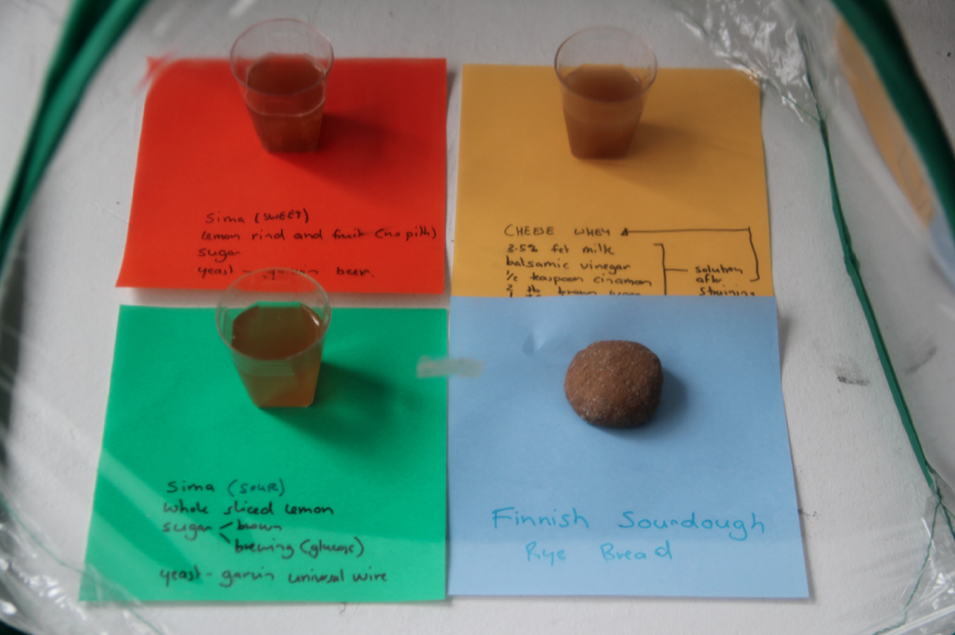

The art of the kitchen is in understanding bio-technologies. The reaction of acid to alkaline, the emulsion of oil and water, the chemical breakdowns during fermentation are all part of the alchemy that comes about during the making of our food. Brian Degger (Australian, living and working in the UK) ran evening workshops on how to make different fresh cheeses, Finnish sourdough bread and Finnish Sima beer – a beer that blends surprisingly well as a mixer for the rum, vodka and gin that we’d brought in to escape Norway’s punitive alcohol taxes. The rigours of making Finnish sourdough bread are now being practiced in Bergen, Berlin and London from the starter created in the MigAA Food / Biotechnology / Neocolonialism workshop.

Bon Appetit!