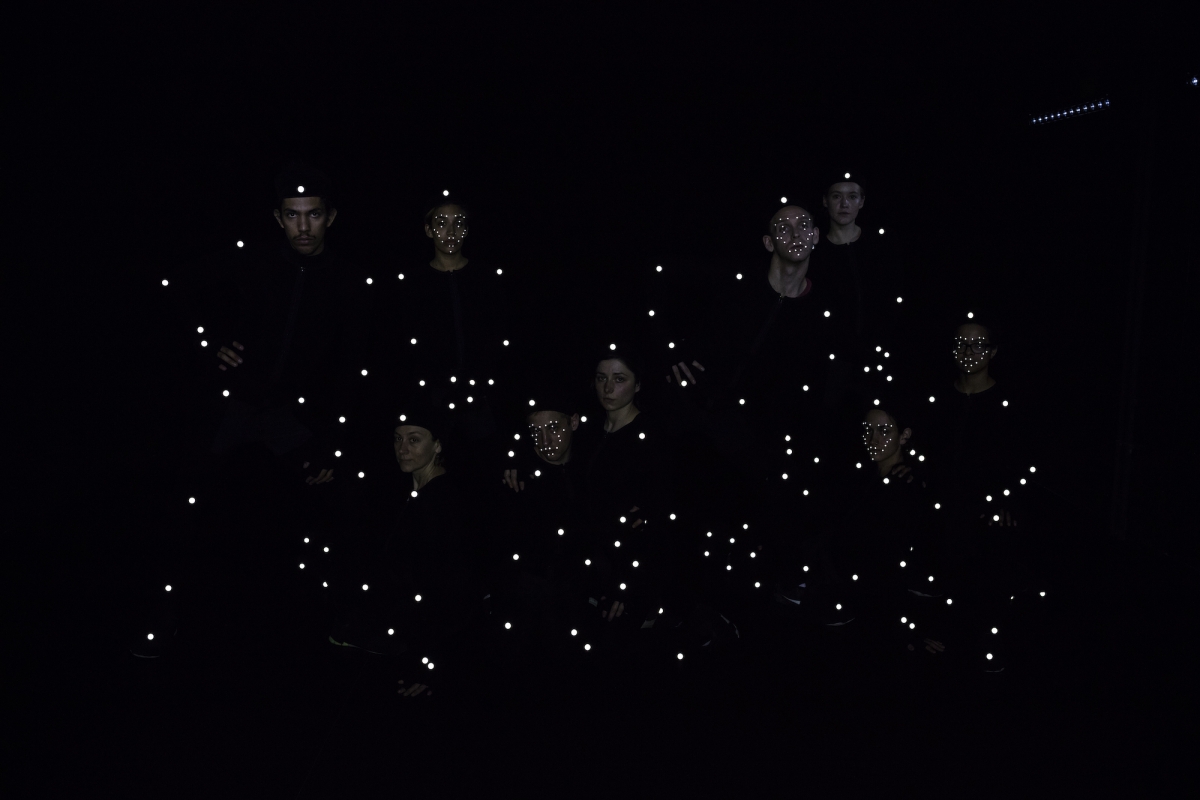

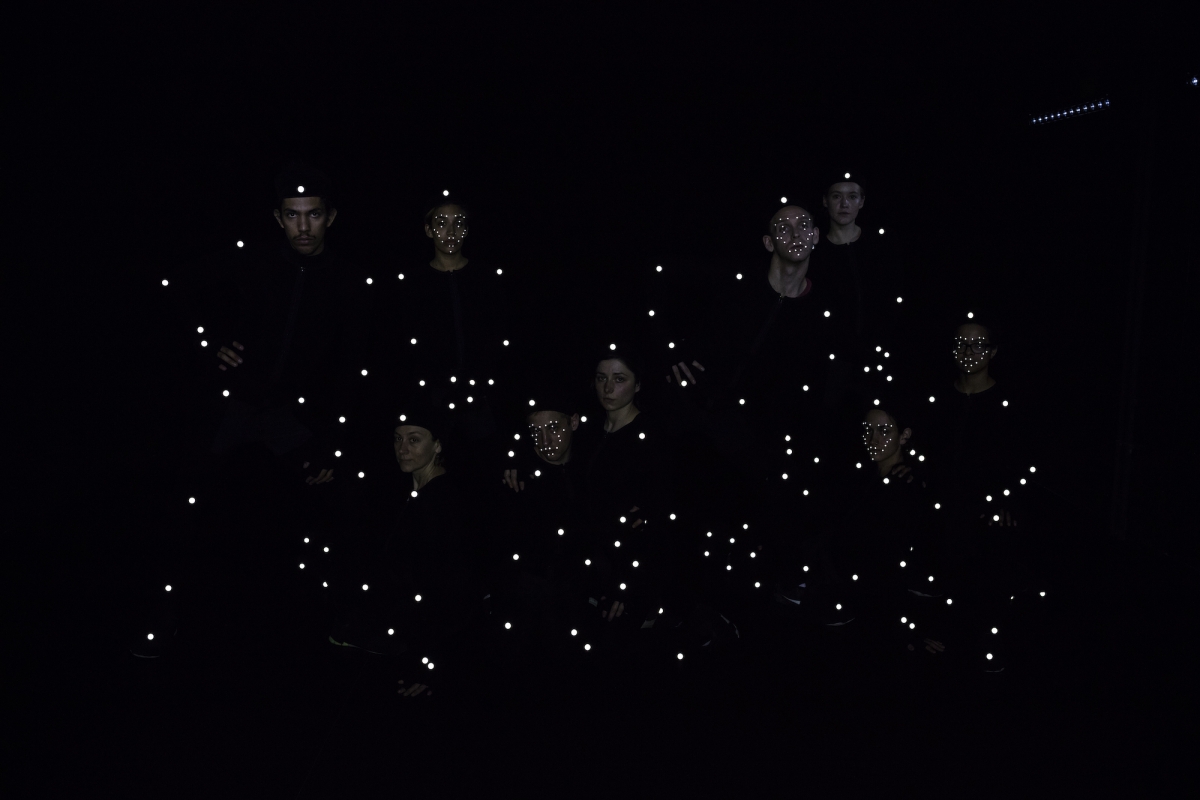

Alexandra Pirici, Signals, 2016. 9th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art (Installation view), courtesy Alexandra Pirici, photo Timo Ohler

Understanding of the contemporary art field’s economy is fragmented and notoriously immersed in mystique.[1] The fragmented nature is often attributed to the economy lacking in a clearly identifiable empirical imprint that could transcribe the field into quantifiable data, feeding econometric analyses, substantiating macro-readings and theorisations. Meanwhile, the mystique may be seen as both a product of this condition and its compensation mechanism, propagated by anecdotal relay of information, clichés and the media’s (as well as the contemporary art world’s) predilection for sensationalism, as showcased by the extrapolating conclusions drawn from the staggering auction sale prices for the works of such big hitters as Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons and Gerhard Richter.[2] From the position of an outside observer, the latter tendency may appear as the only clearly identifiable indication of the art world’s economic structure, but as Olav Velthuis’ and Erica Coslor’s insights into the global art market demonstrate, the disproportionate visibility of transactions at the top level of the market — whether in terms of price or normalcy of such exchanges — tends to misrepresent the field as a whole. There exist great discrepancies between the top end of the pyramid events and the lower end of the pyramid realities, which is where the predominant number of actors and transactions find themselves.

At the heart of the contemporary art economy’s mystique lies the opaque nature of its price-setting practices and the fact that the ‘stickiness’ (i.e. a negative inclination to fall) of art’s prices has a logic that is strategically specific to contemporary art’s socio-institutional and market ecology, which is in turn heavily reliant on reputation, sociality and informal circulation of information. Unlike ‘normal’ luxury markets, sticky prices aren’t so much about communicating exclusivity as is the case for luxury goods, but must be seen from the perspective of contemporary art ecology’s reputational economy and centrality of self-positioning, in which a decline in the price of an artwork could irredeemably tarnish the gallery’s and the artist’s reputation.[3]

Pricing is as a result always an exercise in quantifying projected hype subject to the particularities of an ecology, in which a decision on price is part and parcel of a larger strategy of reputation-setting over time. This process of strategic communication of identity (a.k.a. branding) functions as an important vehicle in generating hype and differentiating oneself in a product-rich market. Consequently, brand emerges as a crucial referent for buyers: ‘for many collectors, buying an artwork is akin to buying an equity stake in [an] artist, whether these returns are psychic or financial, as both the artist’s fame and possible prices depend on work done before and after’.[4]

While there certainly exist single name artist brands who may have consciously exploited the affordances of the hype-hungry contemporary art market to build their super-star status, often positing this as the main commitment of their ‘practices’, group branding is a more prevalent strategy.[5] The latter allows multiple actors to benefit from the circulation and visibility of a single pseudo-movement tag that has been attached to a set of individual artistic practices. The expediency of branding via herding is clearly reflected in tag-themed (whether explicitly or implicitly) group shows, collections and even gallery brands that align themselves strongly with a particular tag.

Primary and secondary market actors — galleries and auction houses — are also brands, although of a slightly different order. While some of their brand may derive its identity from the kinds of artists that they represent/sell, the core of their brand is to be found in their ‘trustworthiness’ mediated via their sectorial heft, which in turn is dependent on their power position within the socio-institutional ecology of the contemporary art field and the nature of their collector base. Consequently, price plays a strategic role in ensuring that a work lands in the rights hands — whether it is a collection that would amplify the significance of the work or a prestigious institutional setting.

This means that pricing an individual work is not just about ‘selling equity’ in a particular artist/tag brand but is also always a question of the gallery’s status in the socio-institutional ecology of the field as well as a question of securing a certain pedigree of a collector base, with the latter two factors operating in a mutually reinforcing manner. Thus, for a gallery, getting the correlation between projected hype and the value appreciation curve right as well as ensuring that all the auxiliary conditions are optimally aligned is an exercise in highly contingent fine tuning that if successful, can set off positive feedback that steepens the curve to reach meteoric heights.

However, the meteoric rise stories are relatively rare, and given the multiple contingencies involved in building up monetisable hype for a primary market actor to stay in business, economist Canice Prendergast identifies the art market’s in-built propensity to move towards oligopolistic structures, and on the level of demand, to opt for blue-chip names:

The art market increasingly resembles a winner take all market, where a large fraction of expenditures are concentrated on a small number of artists (and indeed galleries). There are (at least) two sources of this: (i) the artist’s (and gallery’s) name as the measure of quality, and (ii) a desire by many collectors for ‘trophies’.[6]

It becomes apparent that while the ‘art boom stories’ are inaccurate in their depiction of the art market as a whole, they reveal something fundamental about its nature; namely, that it’s a right tail market (i.e. a market with a propensity to sell a low volume of highly prized goods), in which hype has the capacity to generate high returns for a very limited set of actors, while this golden sliver is what’s being chased after on both sides of supply and demand. This also means that as a winner takes all market, the contemporary art market is structurally pivoted to privilege the already privileged, whether it’s a gallery with a powerful brand, an artist with a strong position in the socio-institutional/market ecology, or an institution/collector with a consolidated status (and of course, purchasing power). Consequently, the winner takes all logic also functions as a mechanism that re-entrenches existing power configurations, making the market and the general socio-institutional ecology ever more elite and impenetrable.

This is not to say that there are no pressures being exerted on this tightening top-tier consolidation. Firstly, the scramble to the top means that the market bubble is constantly moving towards greater likelihood of combustion. The fact that it does not burst is in part to be attributed to the lack of regulation that makes collusion permissible, and in part to the lack of transparency that makes it go unrecorded. Meanwhile, the top-tier is constantly being replenished by ‘fresh blood’ that has made the transition from the ‘emerging’ scene (which is most often funded, either covertly or overtly, by blue-chip galleries), whereas on the side of supply, where barriers to entry are generally high and dependent on personal social networks, the replenishment of liquidity flows stems from the increase of disposable incomes of top earners with the advent of neoliberalism.[7]

Politics of Resale

The question of ‘controlled replenishment’ on the supply side is intimately tied to the problem of the art market’s illiquidity. The latter is a consequence of artworks being difficult to resell at secondary market outside the auction house and dealer networks, which only cater to the top sliver of the art market. Meanwhile, galleries may help resell the work that they have sold previously, however, there is a strong reluctance to normalise and regularise such practice via visible and accessible channels. Strictly economically, it is of course far more advantageous to draw artworks for sale from the gallery’s inventory rather than from the inventory of their clients; this would be the case for any market. However, unlike most markets that trade in durable goods, the primary market actors in the contemporary art market have a tight control over the ‘flows’ tap when it comes to the systemic conditions of ‘stocks and flows’, which means that price ‘distortions’ are inherent to the normalcy of that market.[8]

The stocks are the goods that are readily available for sale on the primary market, whereas the flow is composed of goods that enter the market from both primary and secondary markets (i.e. resales), with the price of a good being determined by the supply from both directions. By closing off/tightly controlling the flow from resales, primary market actors can set prices that correspond to their strategic imperatives rather than any other criteria. Apart from constraining liquidity, lack of a diverse and normalised secondary market leads to ‘distortions’ on the primary market, which are significant not because they deviate from what prices could have been if the market was subject to ‘perfect competition’, but because these ‘distortions’ reveal the authoritative power enjoyed by the ‘distorters’ within the contemporary art regime.

One argument that is often used to justify this infrastructural constellation relates to the ethico-institutional role of the gallery vis-a-vis the development of artists’ careers. Since galleries don’t just position themselves as market brokers, but also as professional guardians, the prospect of opening up the market to other actors is construed as a major threat to the interests of the art field in general insofar as it would make the overall ecology highly volatile, and hence even more precarious for its lead producers. To this extent, the fairly recent scandals surrounding flipping (i.e. purchasing an artwork by a value-appreciating artist and quickly reselling it for profit, sometimes orchestrating a series of resales to increase total profits) provide a good example of the ‘evils’ that are said to be associated with letting ‘foreign bodies’ penetrate the protected zone of contemporary art.[9] However, it seems that this cataclysmic approach is overstated, and the more pertinent question is on what terms does the opening up of the secondary market take place?[10]

In fact, there is cause to consider the ecological volatility and professional precarity of the contemporary art ecology as being indebted to the winner takes all/right-tail syndrome and the monopolistic distortions that are caused when some ‘galleries and artists make most money, but at the expense of a stock of unsold work sitting in storage’, and most importantly, the rest of the field.[11] This effectively causes a bifurcation of the field between a very select group of actors with access to high profit margins and the rest who are just about trying to survive.[12] This situation is both mediated and entrenched by the pressures on regionally and locally organised markets to join the global circuit for visibility, branding and transnational legitimation that can be capitalised on locally/regionally, as well as opportunities to access the top-tier complex with its highly prized clientele and institutional possibilities (e.g. inclusion in exhibitions at established museums).[13] There is a mutually supporting dynamic between the ever-intensifying chase to the top and the integration of new markets that is produced when globalism is posited as an essential constituent of operating within the contemporary art regime, both onto-ideologically and as a business model.

From the perspective of the contemporary art regime, the allure of ‘new markets’ is as much about glocalising the narratives of contemporary art in order to justify its global relevance as it is about tapping into new networks of locally/regionally formed economic elites. This is starkly evident in the attempts to diversify geographical representation at major contemporary art fairs and the desire of major museums to reinterpret their art historical cannon on display towards a more ‘multipolar’ vision, which is protracted into collecting policies tied to the establishment of regional acquisitions committees composed of HNWIs and other representatives of local/regional elites. The decision-making processes and their rationales remain almost entirely exclusive to these privileged cohorts, reflecting the standard modus operandi of contemporary art regime’s ‘imperfect information’.

Information before Art

In an opaque right-tail market, information itself is a highly prized asset, only delivered to the right kind of client. In this sense, when we talk about stark informational asymmetries between the insider actors ‘in the know’ and those outside of these privileged networks, we are effectively describing — as Suhail Malik has correctly identified it — a cartel formation,[14] which from an economic point of view is only a logical step away from an unregulated oligopolistic market. In the contemporary art regime, cartelisation operates on two mutually reinforcing levels: at the socio-institutional level reflected in the ethico-political principles that revolve around art’s exceptionality, and at the level of market dynamics, which as has been described above in relation to stocks and flows, leads to highly concentrated price inflation.[15]

While cartelisation and a right-tail market arrangement may be viewed as two sides of the same coin, what ultimately allows this configuration to be kept in tact and entrenching is at the structuring heart of the contemporary art project, and I would argue that it is the control over the informational landscape which is contemporary art. The roots of what constitutes contemporary art are to be traced via the most basic question, which is, ‘what makes something contemporary art?’ Despite being trivial and somewhat circular, the answer to this question — ‘whatever is seen as contemporary art’ — institutes an algorithmic logic that is amplified systemically and resonates in all corners of the regime.[16]

As has been noted by various authors, the lack of substantive intrinsic criteria that cause something to be contemporary art results in the socio-institutional setting not only serving as a purely institutional gate-keeper but also as a purveyor of ontological inauguration.[17] Thus, framing and social insertion become the critical devices for being contemporary art. Since both of these strategies are dependent on what Elena Esposito calls ‘second-order observation’ — gauging what others think in order to formulate one’s own position, what remains repressed is that when raised to the abstract level of ‘the art world/the art field/the art market’, the ‘herding syndrome’ produces clusters of reflexive resonances that then appear to be the reality that we call contemporary art in its core formation. It is from this perspective that we can say that information is contemporary art, hence introducing a more expanded understanding of information in the context of contemporary art.

One can then understand the contemporary art ecology as an unevenly distributed informational terrain with highly concentrated clusters of reflexive activity that effectively serve as mountain beds for the sharp peaks of transactional exchange. The ‘mountain beds’ are the loci of gregarious behavior that are formed through the interlocking of wider institutional and market activity, which is amplified further and further through a series of positive feedback loops, producing augmented visibility and consolidating the status of its lead actors (artist, gallery, key institutional actors, key publications, key financial benefactors, etc). The clusters are networked into a larger constellation of similarly concentrated zones of reflexive activity, serving not only to delineate a ‘field’ but also to boost the status of the pre-existing entities with weighty reputation as these become the links through which new clusters fashion their appearance.[18]

An actor’s comparative advantage isn’t so much about having access to information about a pre-existing state of affairs but it is about one’s positionality: how/where others see you relative to the highly concentrated clusters of reflexive activity, and hence the power that you possess in shaping the informational terrain towards your advantage. Such approach deviates from the one where information is a pre-packaged given with highly asymmetrical entry points.

Power as Reflection

The ambiguity in understanding information in contemporary art as a reflection of an existing state of affairs, which coalesces with the description rendered in the very beginning of this essay — the ‘empirical imprint’, and information as a reflection of reflections that actually constitutes what is considered to be a market, is also to be found in the divergences Elena Esposito highlights between the neoclassical understanding of information and the one that she puts forward in The Future of Futures. Neoclassical economics tends to position information as a neutral reflection of the state of the market at a given point in time that should ideally be accessible to all market actors in order for them to make ‘rational’ choices; hence, the criterion of perfect information that produces transparent efficient markets, and the market’s inbuilt tendency to strive towards equilibrium.

Elena Esposito shows how perfect information and transparent markets are in fact examples of neoclassical delusions[19] that ignore the reality in which ‘information, far from being evenly distributed and available to everyone, is the factor that enables gain’, and is the rationale that drives market activity.[20] It is worth quoting Esposito at length:

Behavioural finance demonstrates that the behaviour of investors cannot be explained on the basis of explicit information alone, but, nevertheless, should not be dismissed as irrational. […] People often rely on information that may appear irrelevant if one refers only to the alleged ‘fundamentals’ of the economy, including voices and ‘rumours’ circulating in the markets (noise), contexts and backgrounds of the news that affect their reception (framing), and a widespread perception of ‘market sentiment’. These forms of information are far from balanced and tend not to compensate in the way foreseen by the theory of efficient markets. On the contrary, they often intensify and reinforce themselves through a positive feedback mechanism, where investors buy in response to an increase in prices and sell in response to their decrease — that is, where investors make decisions based not on the explicit information contained in prices, but in reference to the additional information they read in prices, following trends and the perceived behaviour of other investors. The market, in this case, does not behave like a filter, neutrally transmitting information about the world, but becomes the real object of observation. Investors turn their attention to the market and its dynamic, neglecting goods and commodities.

Although referring to financial markets, this seems to be a very fitting description of CA’s socio-institutional and market ecology. The ‘fundamentals’ such as information about price and transactional history are actually secondary to the ‘noise’ of seasonal hypes, ‘rumours’ of mid-career retrospectives at major institutions, and contextual contingencies that allow for noise and rumours to potentially follow completely divergent trajectories depending on the nature of the operating contingencies at the receiving end. The ‘positive feedback mechanism’ that is set off when a resolute sentiment gains enough traction is the process of constitution through information, in which artworks, artists and discourse recede into the background, and the observed movements relative to one’s positionality take centre stage. Some aspects of this dynamic are captured by Canice Prendergast when he describes the structuring logic of the art market as one of a ‘beauty contest’ — an analogy originally coined by Keynes in relation to stock markets:

Beauty contest markets are those where buyers care about what others think when they decide to buy. […] There are two implications of this: bubbles, where prices drift far from true fundamentals, and herding or groupthink, where most people’s information does not get incorporated into prices as people see more with their ears than with their eyes. […] These markets are prone to bubbles. There has always been a suspicion that beauty contest logic can cause prices to drift far from their fundamental value (‘I’ll buy at this crazy price, as I think I can sell to you at an even crazier price, and you think you can sell on to someone else at a yet a crazier price’, and so on…). […] The inherent subjectivity of art makes this a prime candidate for such bubbles.[21]

While the ‘beauty contest’ paradigm provides an apt illustration and is certainly true to form, it tends to reduce this state of affairs to a superficial hunger for status as the overarching proclivity of the contemporary art ecology, whereas it seems that the more pertinent conclusion to be drawn relates to the implications picked up by Keynes and Elena Esposito in relation to anticipatory and reflexive pricing tactics. Just as access to information is not the pivotal locus of gain but rather the latter emerges from the positionality of an actor endowed with the capacity to construct the informational field, the ultimate ‘trophy’ is not the possession of an artwork or asset/capital desired by others but being in the position of an actor whose movements are taken as indicative of where the wind is blowing. If the tendential reorganisation of the modern economy qua financialisation has effectuated a systemic detachment from the ‘underlying’ and not just simply a loss of stable references vis-a-vis valuation,[22] this logic is not only reflected within the contemporary art regime but accelerated through the latter’s affordance of transforming liquidity and access to informational constitution into power.

[1] See Josh Spero and James Pickford, ‘Art market ripe for abuse, say campaigners’ (Financial Times, April 17, 2016) [accessed on http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/d5098c7e-018c-11e6-ac98-3c15a1aa2e62.html#axzz48o7p6Qpr]

[2] See Oliva B. Waxman, ‘An Orange Balloon Dog Sold for $58.4M So Here Are 10 Other Cool Jeff Koons Balloon Pieces’ (Time, November 14, 2013) [accessed on http://newsfeed.time.com/2013/11/14/an-orange-balloon-dog-sold-for-58-4-million-so-here-are-10-cool-jeff-koons-balloon-pieces/]; Kate Connolly, ‘Amount of money that art sells for is shocking, says painter Gerhard Richter’ (The Guardian, March 6, 2015) [accessed on http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/mar/06/amount-of-money-that-art-sells-for-is-shocking-says-painter-gerhard-richter]; see ‘Andy Warhol auction record shattered’ (BBC, November 14, 2013) [accessed on http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-24937683].

[3] Canice Prendergast, ‘The Market for Contemporary Art’, November 2014 [accessed on http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/canice.prendergast/research/MarketContemporaryArt.pdf]

[4] Prendergast, p. 8.

[5] Most recently, this has been clearly evident in relation to the ‘post-internet’ tag, which over a couple of years has moved from a marginal trend associated with a younger generation of artists living in Berlin and New York, to a transnational preoccupation paraded in contemporary art’s most reputable institutions.

[6] ibid, p. 9.

[7] See Madelaine D’Angelo, ‘Is there a Bubble in the Art Market’ in Huffington Post (November 24, 2015) [accessed on http://www.huffingtonpost.com/madelaine-dangelo/is-there-a-bubble-in-the_b_8630434.html]

[8] Prendergast, p. 17.

[9] See Katya Kazakina, ‘Art Flippers Chase Fresh Stars as Murillo’s Doodles Soar’ in Bloomberg (January 7, 2014) [accessed on http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-02-06/art-flippers-chase-fresh-stars-as-murillo-s-doodles-soar.html]

[10] Olav Velthuis, ‘Artrank and the Flippers: Apocalypse Now?’ in Texte zur Kunst (Issue no. 96, December 2014). See contrasting approaches: Flipper Extraordinaire, Stefan Simchowitz (http://www.artspace.com/magazine/interviews_features/how_i_collect/stefan_simchowitz_interview-52164]; Seth Siegalaub’s The Artist’s Reserved Rights and Sale Agreement (1971) (http://www.primaryinformation.org/the-artists-reserved-rights-transfer-and-sale-agreement-1971/_); Real Flow ‘Art Is the Sublime Asset’ (http://www.p-exclamation.com/wp-content/uploads/Real-Flow.pdf).

[11] Prendergast, p. 13.

[12] Gregory Sholette, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (London: PlutoPress, 2010).

[13] Horowitz, p. 17.

[14] Suhail Malik, ‘Civic Virtue in Neoliberalism and Contemporary Art’s Cartelisation’ in 13th Istanbul Biennial Book, 2013, pp.130-152.

[15] A stronger claim would be to state that primary market actors engage in price-fixing behaviour.

[16] See John Roberts, ‘Art After Deskilling’ in Historical Materialism (18, 2010), pp. 77–96 [accessed on http://platypus1917.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/robertsjohn_artafterdeskilling2010.pdf]

[17] See Armen Avanessian, Amanda Beech, Suhail Malik, Robin Mackay, ‘Beyond the Contemporary’ in Spike (Summer 2013), pp. 90-104 [accessed on http://amandabeech.com/Writing/Beyond%20The%20Contemporary/PDF/BeyondTheContemporary.pdf]

[18] This clearly evident in the fact that the list of the most reputable blue chip galleries and contemporary art institutions has not changed much in the last twenty years. New players appear but their status is always underwritten by a link to the established actors, which only re-consolidates the status of the latter. A somewhat comical but very telling symptom of this tendency is the frequency of Hans Ulrich Obrist’s inclusion into contemporary activity across the globe, which has led to jokes about the curator’s ability to clone himself in order to make himself available for all of his publicly visible commitments.

[19] See also Donald MacKenzie on Milton Friedman in An Engine, Not a Camera: How Financial Models Shape Markets (Cambridge, MA/London: The MIT Press, 2006) pp. 9-10.

[20] Esposito, p. 66.

[21] Prendergast, 25.

[22] Suhail Malik and Andrea Phillips, ‘Tainted Love’