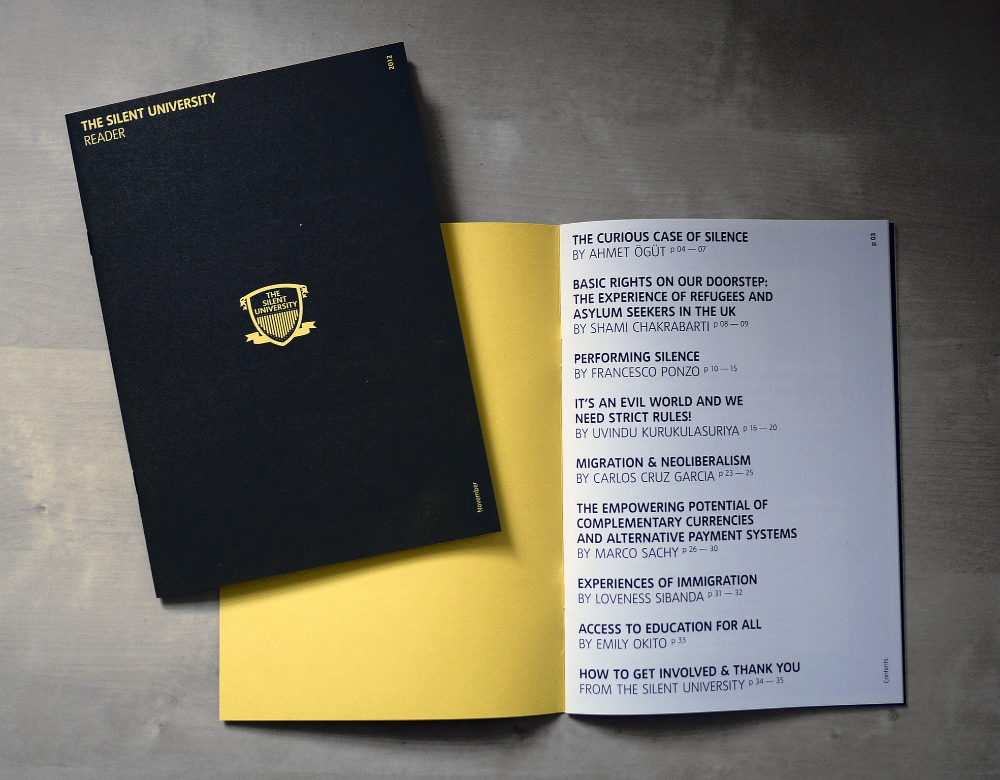

Silent University at Delfina Foundation, London, 2012 ©Ahmet Ögüt

Maya Mikelsone: Ute, can you tell how the art education system has changed in relation to economical context from the time you were studying until today?

Ute Meta Bauer: It depends on the school. In Germany and Austria art education was still structured in a master school system, when i became a professor in 1996. This should not be mistaken as a master course, what it meant was that an art student stayed for several years under the wings of one professor – the master, and knowledge and skills were transmitted from one generation to the other. I attended the university for the arts in Hamburg, a kind of post -68 model, that was very open, and once move freely between classes and professors.

MM: Today art students are prepared to find a gallery, to be professional artists and to be a good manager as well. Were you trained to become an actor of the art market?

Ahmet Öğüt: The changes within the last years have taught us, that especially in countries lacking public and governmental funding for art and culture, there is a strong shift towards the private sector and the commercial system and therefore private foundations, banks, wealthy families and commercial galleries become the main supporters of contemporary art and culture. These developments also have massive impacts on the overall attitude of the students towards their education, their art and their carriers. Most students expect to be taken on by a gallery or an art dealer that will establish them on the commercial art market immediately after graduation. That is what we are currently witnessing in the US.

MM: Also in France.

UMB: The same in London. If you charge such a high tuition fees, you understand the importance of the market to this generation of art students. When we studied it was normal that only in your thirties, or forties you might be represented by an influential gallery. To have a one-person show in an important museum you had to be most likely in your fifties. For a female artist doors were not that open neither in galleries nor in museums. But there was also a lot of freedom, because the arts were less market driven. One had a job to earn a living and did art in parallel.

AÖ: Within the last six years we have been experiencing massive changes in Turkey. When I went to University it was exactly the way Ute just described. While we were studying it didn’t even occur to us that it might actually be possible to make money from our work. At that time we were producing our art from an entire different background and motivation.

UMB: It was more about living an interesting life, not to be ruled by anyone. It was more playful, maybe a little bit too romantic. As young artists we faced less economical pressure than the artist generation today. The art world wasn’t as professionalized as it is the case now and the scene was much smaller. It was also a time of discovering spaces outside museums. The attitude of do it yourself and do-it in the street, to develop your alternative scene we took over from two generations before us – the conceptual artists, as we wanted to distance us from the movement of the “Neue Wilde”, who distanced them from the academisation of conceptual art. I was working with an artist group called “Stille Helden e.V.” and we found an old factory in Hamburg where we curated two larger shows with guests. We showed installation; a few of us formed a band called “Paris ruft”, we did performances, were shooting films and hold readings. In this way we became quite anti-discplinary and were more critical than our professors towards the art field. It was indeed another moment of institutional critique but at the same time we were also little bit naïve – we truly believed we are the world, without even traveling to other continents. Today art students can’t be that naïve anymore, they are forced to be professional from the moment they enter the art school.

AÖ: I agree, it is essential to maintain a certain degree of naivity and autonomy within and towards your own practice over the years – irrespective of how positions change.

UMB: From what I really benefitted as an art student back then, was the openness, the moving between media and the understanding of different fields such as film, theatre and dance, music and literature. But I also realised that I’m equally interested in what my peers do. We hardly showed alone, it was really a time of collective activity and that was accepted and respected also by the “official” art world. It was easier to negotiate a space, we actually received support for our projects although we were quite young at the time. This is more difficult for art students today, instead they might be able to receive grants to study abroad, to go for a student exchange and there are more artist in residency programmes then back then. Today it is already about crafting the right CV while still in art school.

AÖ: Ute, how would you describe the students’ relation with art institutions when you were studying? Did they start as interns or there were other alternatives?

UMB: For me it was a question of day-to-day income. I worked for nine years in various jobs at the Kunstverein in Hamburg to support my studies, not to enter the field. But at Kuenstlerhaus Stuttgart I indeed consciously took my first job as artistic director to have a financial base and also a space for a programme.

AÖ: So you started out at Kunstverein in Hamburg with a paid job?

UMB: Yes. But believe it or not my first job there was as a cleaner, definitely not what I would consider an internship. Next I worked as a guard and installer, I developed their photo archive, worked on loans in the office. All those tasks to my living as an art student is what I would call my practical education as a curator.

AÖ: All within the same institution?

UMB: Yes, many art students would work at the Kunstverein in Hamburg as installers and guards, selling tickets, and the art history students would do the guided tours.

The next job for us was to implement hundreds of power plugs into a former factory area called “Kampnagel” for «Art in public space» office of the City of Hamburg. This was a pretty well paid job, and it generated the funds for our first big show in one of the factory buildings at “Kampnagel”. But the then director of the Kunstverein, Uwe M.Schneede came out of the 68 movement and kept the Kunstverein very open for student jobs, and those became part of our “real life” formation next to what we learned at the art school.

MM: There is an art education reform in France since some years and there is a lot of discussions lately about relation between practice and theory. Can you compare your experience in MIT versus that at the Royal College?

UMB: To answer I would have yet again to go back to my own education. I initially studied stage design. We attended a weekly seminar in dramaturgy that was required, as in stage design one works with texts, with screenplays, with scripts. We were reading a lot of different material and I enjoyed this a lot. The Fine art students didn’t had to this. Also we were the first generation to take diploma exams requiring a project and a written thesis. I had to relearn writing, as during the studies we never had to write anything. When I became a professor at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the Academy of Fine Art Vienna I made sure our students did not only read but also got familiar with writing. To me it is part of the art education to be able to reflect your own work that of your peers and to be able to analyse what is going on in the field in which you operate. At MIT our Visual Arts courses are open to all MIT students of all disciplines. There are always theoretical and practical components that are taught with each course. At the RCA again the way to teach is very different. The RCA is postgraduate awarding master and research degrees and the relationships between teacher and students are based on individual or group tutorials. Seminars of course exist as well, but they are not the core of the curriculum.

MM: Do you think that art students need strong theoretical basis?

UMB: I don’t think one can teach someone to be an artist, but one can teach through art, through critical writing and through theory what artistic practice entails. We know that a large percentage of our students might not become artist with a big A. They might teach art and visual studies, some want to become writers, some designers, and even those who indeed will operate as artists as its commonly understood might benefit from a broader range of knowledge. And there is not one way to make art, to navigate the art world, its crucial to be always clear that there are other ways of working as an artist or what might art be, beyond ones own understanding of art.

AÖ: I agree. I was enrolled in Hacettepe University’s Fine Art Faculty in Ankara for a BA in painting, however not with the idea to become an artist but to become an actual painter. I was very confident about my choice, which, in the end – as we well know – nevertheless didn’t happen. I would have had the opportunity to study interior design, but at that point I didn’t see how that would relate to my interest. Looking back I realize that no matter whether I had studied Interior Design, Architecture, Engineering or Design in general, I would have continued developing my own art practice anyways – and actually holding that kind knowledge and experience would sometimes prove useful today.

In general it is hard to confine your interest to one specific direction, especially in the beginning, when you are just stating out. The most important thing seems to be that we develop an ability to coordinate all the various knowledges we have acquired over the course of our lives and cross, intersect and merge them in new and experimental ways. Therefore the structure of educational programs should be open and flexible and not restricted and fixed.

UMB: This is what I appreciated at MIT. The the students who pursue a master degree in Art, Culture and Technology come with clear idea of what they want, they are often surprised to be confronted with students from different fields in our classes and workshops. Those who study physics or architecture approach certain topics very differently. To study art at MIT is way more challenging and complex, as you will be constantly exposed to people who bring something different to the table. What is also important is to rethink the role of teacher and student. As a teacher you might know more materials as you are at least ten years ahead of your students, you might have read more books, saw more exhibitions, travelled to more places. But your students have the knowledge of their generation and they can give you something in return that you don’t know. I see this more like an exchange rather then me telling them something. At Royal College it is more about deepening your skills in workshops with amazing knowledgeable staff, it is more about exploring your work deeper. Both models are not comparable – they represent simply very different approaches.

Silent University at Delfina Foundation, London, 2012 ©Ahmet Ögüt

AÖ: Just recently I had an interesting encounter with some art students from Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm. We had a discussion about the different school systems in Sweden, other European Countries and the US developed. I had always believed that Swedish students were provided with high standard facilities and everything else they needed, but these students were all complaining. In the end it is not about studying at a good or a bad school, or, let me rephrase, it is not the facilities and the educational standards that decide on the quality of a school. It is about the individuals that come together, share space and time and thereby create the educational environment; you need visionary professors and inspiring classmates. It actually makes a huge difference whether you go to school and study with a professor who is stuck in the academic world or with a professor who sustained an autonomous practice outside the academy.

UMB: I can’t agree completely because In Hamburg at the University of the Arts there were very famous artists like Sigmar Polke, Franz Erhard Walther, Ulrich Rueckriem etc. as professors, of course they attracted very interesting students. At the same time more unknown teachers such as Claus Boehmler in Hamburg, or Fritz Schwegler and Alfonso Hueppi in Düsseldorf taught generations of later very successful artists. It is also about being with your generation, with your peers. We were sharing flats, were going together everywhere – to exhibitions, concerts, to the theatre, we were watching TV together and then we discussed it all. We were from different class backgrounds, came from different cities and countries, and art school was like an umbrella that brought us together. And then there are simply times that are exiting and the early eighties with punk and strong time for indie film, experimental theatre was such a magic moment in Europe.

AÖ: Yes, agree, there are those magnetic moments in time. Again, it is about individuals who happen to be together in the same place at the same time who can learn from each other and grow together.

UMB: There was an evaluation done in 1996 of the situation of artists in Germany and it stated that only 2 of 5 art students enter what we call the art market. But for what are we preparing the other 98% of students that attend (and now pay) our art schools?

AÖ: And why did they study?

UMB: Maybe they become writers, maybe technicians or maybe invent their own jobs. Some might become taxi drivers. But all of them deserve to take some knowledge, some skills with them from these years, something that adds value to their lives.

MM: If thinking about what you get from studies, the problem in Eastern Europe is that the art education system is so old and academic that students are trained as craftsmen but they have a lack of knowledge.

UMB: I had some students that were strong in theory but then had a difficulty with translating it into a work of art, but they still wanted to be artists. Well, you have to figure it out, but we should be always very straightforward and open in our feedback to our students. But what is even more crucial, we should still argue the importance and the value of artistic education. Nobody is questioning why we have to learn mathematics or biology at school even if we don’t become mathematicians or biologists, it should be same in the arts.

Ahmet Öğüt is a contemporary artist born in 1981 in Diyarbakir, Turkey. He co-represented Turkey at the 53rd Venice Biennale together with Banu Cennetoğlu. In 2012 Öğüt completed a year-long residency at Tate and the Delfina Foundation, resulting in the major ongoing project: the Silent University (2012). It is an autonomous knowledge platform for asylum seekers, refugees and immigrants. In October 2013, it opens new branch at the Tensta Konsthall in Sweden and at Le 116 in France.

Ute Meta Bauer is an art curator recently appointed Founding Director of Nanyang Technological University Centre for Contemporary Art in Singapore. Previosly she was the Dean of the School of Fine Art at the Royal College of Art, Founding Director of the Program in Art, Culture, and Technology in the School of Architecture and Planning, Director of the MIT Visual Arts Program and Professor of Theory and Practice of Contemporary Art at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Bauer was also the Founding Director of the Office For Contemporary Art Norway (OCA).

Maya Mikelsone is a Latvian curator based in Paris. She has studied Philosophy of Art at University Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne followed by curatorial training program at École du Magasin.