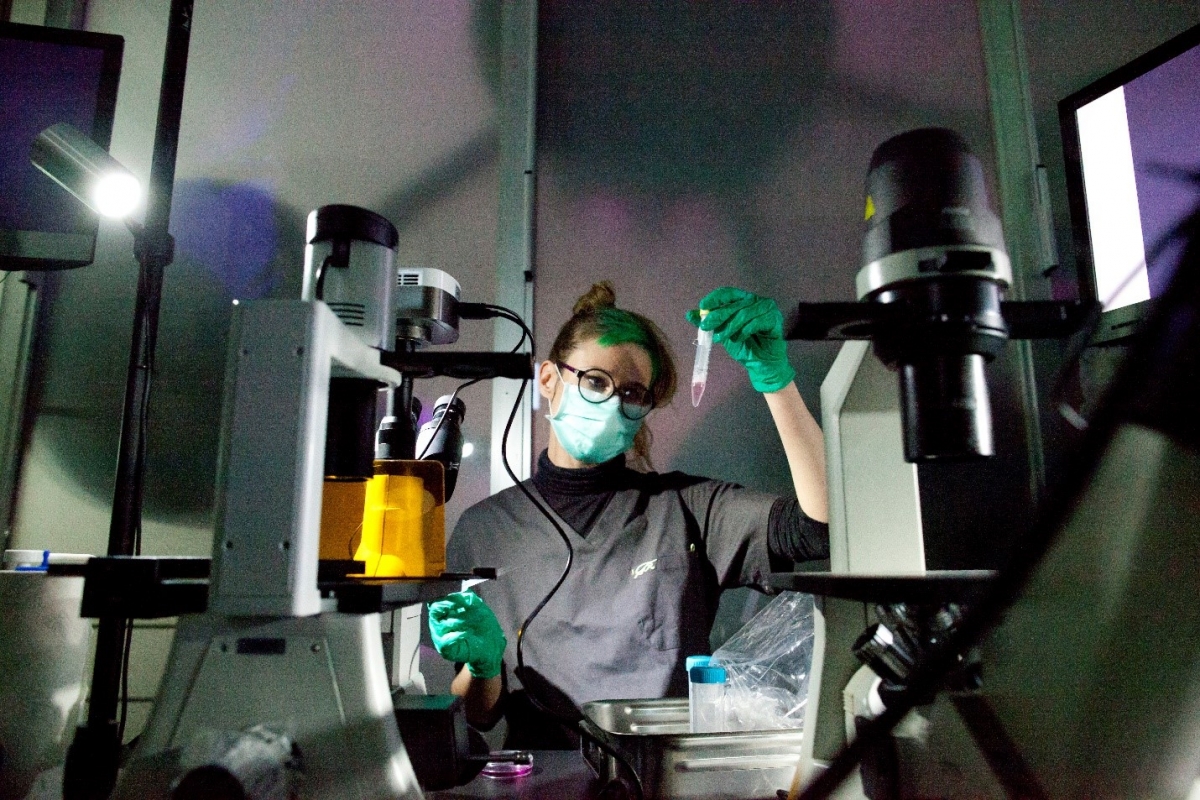

Courtesy of Špela Petrič

Dr. Špela Petrič (1980), BSc, MA, lives in Ljubljana, Slovenia. Her artistic practice combines natural sciences, new media and performance. She is interested in all aspects of anthropocentrism; the reconstruction and reappropriation of scientific methodology in the context of cultural phenomena; living systems in connection to inanimate systems manifesting life-like properties; and terRabiology, an ontological view of the evolution and terraformative process on Earth. While working towards an egalitarian and critical discourse between the professional and public spheres, she tries to envision artistic experiments that produce questions relevant to anthropology, psychology, and philosophy. She extends her artistic research with art/sci workshops devoted to informing and sensitizing the interested public, particularly younger generations. She is a member of Hackteria.

The name of your website has intrigued me from the first encounter and in a way seems like a good starting point to discuss your artistic practice. So what is Life in the TerRatope?

The terRatope refers to the “thick here”, the place we inhabit as much as compose (I embrace the pronoun we in all its slippery inclusive/exclusive, totalising/collective connotations). The prefix terRa can be read as terra, pertaining to the Earth, or as tera, derived from teras, the Ancient Greek word for monster. It implies the fear and fascination of otherness inhabiting the topos = place, which holds a grip on us even if we reject essentialism with its fixed, clear-cut categories and adopt the fluid post-structuralist, new materialist view on the world.

The terRatope is filled with us, beasts coaxed into existence by developments in mimetic and synthetic bio/technology, and our relationships are a mess. To consider us strange means to approach us with an unsettled mix of awe, fear, desire, rejection and care. Instead of assimilating or annihilating monsters, the terRatope calls for making more, which invites new forms of relations and politics. Due to this the terRatope doesn’t contain the same anthropophagic ecological significance as the Anthropocene, it doesn’t evoke defetism. In the terRatope there’s no time to cry over spilled milk, just a need for reframing.

I do believe that the whole universe and its course of events is at fault of something happening at certain moments. Keeping in mind that for many years you were (strictly?) science oriented, what has drawn you to become an artist? How did that happen?

Perhaps it was just a happy accident, though I like to imagine that I had kept my eyes peeled for the opportunity and took the leap when it arose. During the formative years, when students are molded and groomed into the stuff that makes scientists, I was increasingly haunted by an “outside” to this knowledge production, beyond the subjects of the scientific method, that which is in professional circles usually deemed unnecessary, distracting, irrelevant. I needed to understand how this domain is interwoven with and even constitutional to society (as is a common claim about both art and science), since the day-to-day scientific research was an extremely alienating experience and felt more a sacrifice than a privilege. Like many PhD students, I had a bout of depression that allowed me rethink my academic career. I picked up on my interest and engagement in poetry, theater and performance that I had paused while studying biology. Ljubljana is a small city and it didn’t take long before the word of a disillusioned scientist lurking amidst the art scene came round to Jurij Krpan, the curator of the progressive Kapelica Gallery, who at that time was working with the pioneer of Slovenian bioart Polona Tratnik. He was interested in expanding this field and was happy to find someone with a background in science willing to go down the rabbit hole of art and biotechnology. The very first project got me completely hooked. Living organisms and science in the context of art challenged me as a whole and wholly, too – emotionally, intellectually, ontologically – it was unsettling, humbling, rewarding and bottomless. It also motivated me to finally conclude my science PhD and enroll in the Transmedia program at LUCA, Brussels.

Project Naval Gazing. Courtesy of Špela Petrič

Despite of the fact that your website is quite informative on the subjects of your previous projects, it would be interesting to know which one would you point out as most rewarding one, the one that stands out? And briefly what it was about?

That’s a difficult choice to make. Naval Gazing, a project realised in collaboration with Klaas Timmermans from the Netherlands Royal Institute for Marine Research and supported by the Bioart and Design Award, still fascinates me. During a six month collaboration on Texel, an island of the coast of the Netherlands, we constructed a 7,5 m habiton, a six-winged kinetic structure with a tetrahedron center. When released in the sea it would tumble and move, propelled by the wind and currents. The habiton itself is an uncontrollable, large and elegant structure that once released inspires fascination, sometimes it seems mechanical, other times almost alive. Its continuous movement prevents marine organisms from attaching, at least for a while. The habiton writes a story of colonization. What begins as a human-artistic intervention of abstract form into the marine environment, is eventually overgrown with algae, seaweed, barnacles and entangled with objects picked up on its journey. At one point the accumulated weight sinks the habiton to the bottom of the sea, where it is finally appropriated as a living space. The colonizer is colonized and reborn as a habitat. At the moment, having previously been test launched for only a few hours, the habiton is still awaiting the opportunity for its final release.

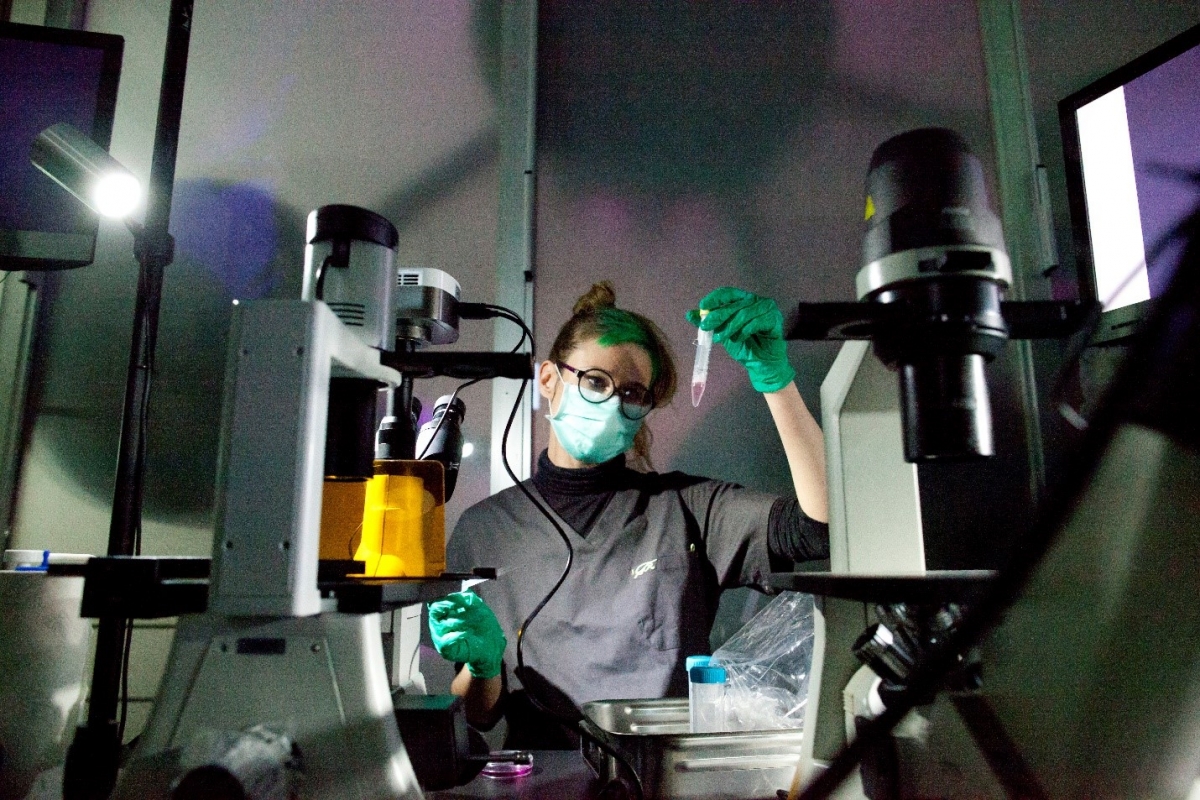

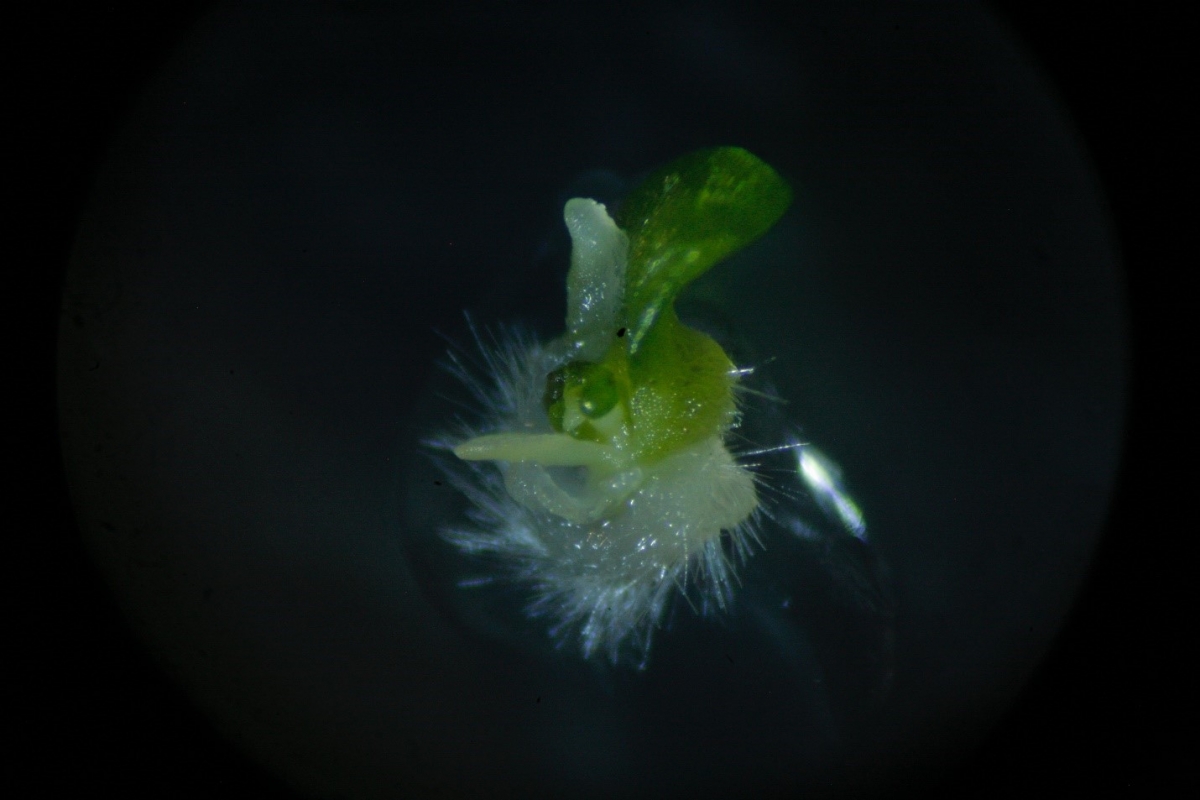

Project Phytoteratology. Courtesy of Špela Petrič

An eco-critical nature/culture discourse puts mankind as one element in a larger ecosystem and questions or maybe even rejects the human-centered world. What is your position towards this approach?

In the current state of knowledge, economy and politics, it would be really hard to argue against a deep interconnectedness and interdependence of processes and beings, but what does it mean to reject a human-centered world? Does it call for an alternative centering or an existence without a center altogether? And who exactly is this human anyway?

Michael Marder proposes to strive towards phytocentrism (plant-centering), which is philosophical joke of sorts, since he argues extensively that plants in fact do not have a center (rather, they have a middle). Phytocentrism is a project of discovering a common principle, that of growth, which finds “centers” in each and all growing beings. It estranges the human to the extent that we are no longer the yardstick by which we can only ever see deficient versions of ourselves in other kinds of creatures. That said, this sliding center can be an exhausting and terribly inefficient way of organizing daily life (it’s even quite a chew for art!), leading to fatigue and indifference.

Lately, I’ve been looking at care as an organizing principle, a way to veer away from the politics of exploitation without the dread of continuously failing to live up to the ideals of post-anthropocentrism and other sexy-but-unachievable constructions. Caring for something or someone is involving, implicating, but it is also a means for the career to become significant for (not necessarily to) the cared for. At this moment the dominant societal affect might in fact be powerlessness, since many of us already find ourselves at the fringe, decentered, precarious and facing uncertainty.

Instead of enthusiastic ‘decenterings’ (which never seem to quite reach their targets anyway), care might be a better antidote to capitalist malaise. But because it’s at odds with scientific objectivity that prescribes distance, this discourse has also remained on the fringe, as a feminist topic.

Do you aim to contribute, even on a microscale, to the improvement of living systems or a given ecosystem?

I do hope to contribute – something – an examined life and a specific flavor of care? What I’ve come to understand is that improvement means different things to different entities and that improvement is also an ideological imperative and that not all things want improving. That said I will scream and fight to make space for the weeds, both metaphorical and literal.

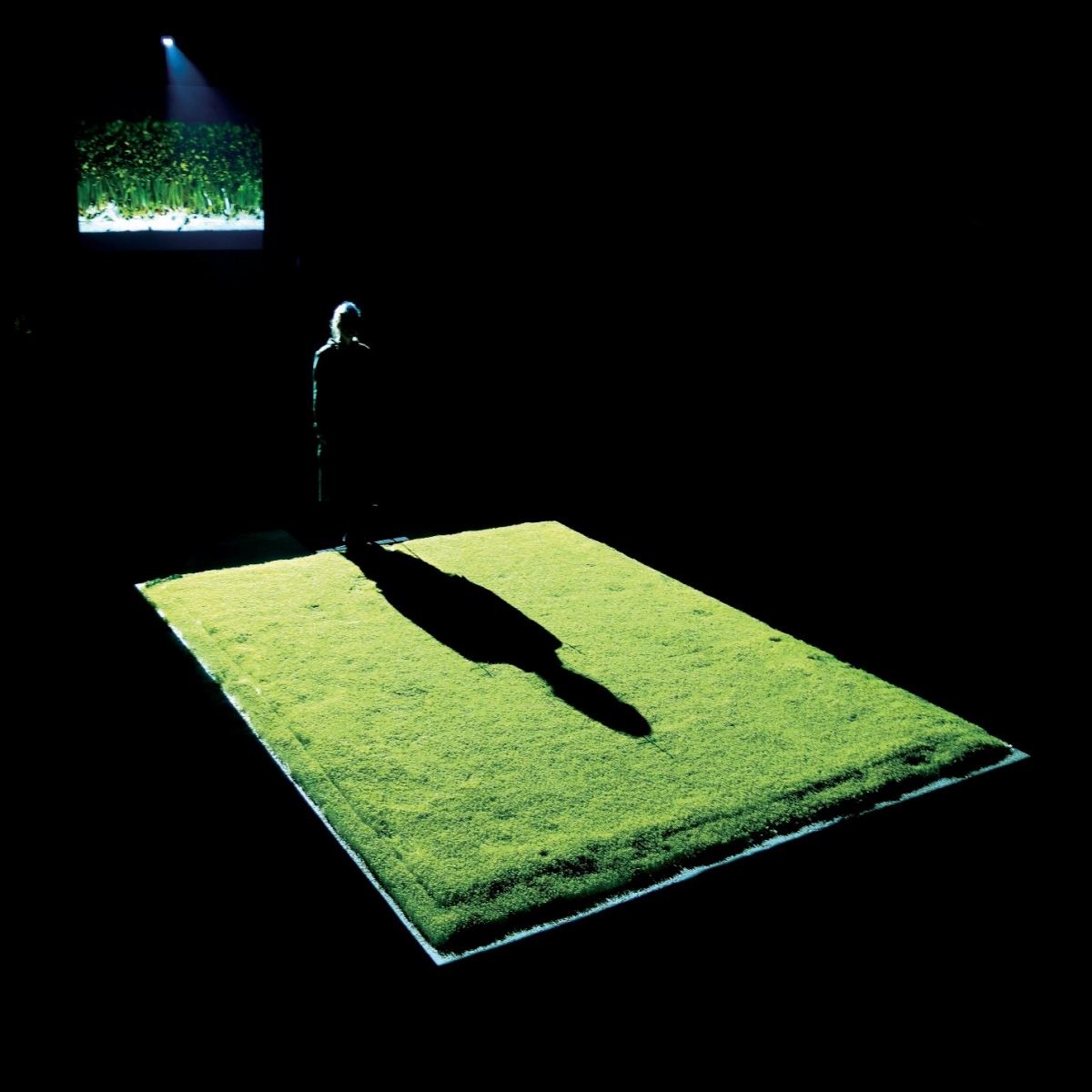

Confronting Vegetal Otherness. Courtesy of Špela Petrič

Of course, science as a tool for creativity and implementing unique approaches can be truly rewarding. Does your scientific background get in the way of the creative process, let‘s say, rationalising it?

There is no way to answer that question without being born again, at least twice, studying art and, as a control, not studying at all, then comparing the creativity not influenced by science to its current state. Haha. We are all significantly shaped by our experiences, especially the ones which are diligently practiced. A bit of the science background is in the way I perceive and act, it connects me to a body of knowledge I’m comfortable navigating. On the other hand, the past 8 years working as an intermedia artist have left a significant mark as well – in terms of opening up to materiality and embodied ways of knowing, collaborating in multiplicity and without consensus, also learning to survive in the art-network structure.

Having experienced two very different domains quite intimately, I observe the hidden ways in which technoscience helps to maintain the social and cultural landscape through an affirmation of certain values and worldviews that are complicit with the current economic system. The alliance is not all that surprising since humanism, science and capitalism all have origins at roughly the same time and place in history, but perhaps the ways in which these have persisted, adapted and become invisible is.

I’ll give you an example of this insidious abduction which I experienced working on the Confronting Vegetal Otherness opus. My best attempt at performing artworks that would be respectful to plants and their agency to me meant avoiding the violence of anthropomorphism, to avoid projecting my humanness onto them. Instead, I investigated molecular connections, material biosemiotics and intercognition, the proof of which was inscribed onto the bodies of plants as well as my own. However, the process of making these artworks was disconcerting for me; the act of tending to the plants created an attachment that never grew into the sentiment I expected. I couldn’t understand, was I in fact my worst fear, the cold hard navel-gazer (ab)using plants to get ahead in the art world? I think it was anthropologist Natasha Myers who hinted the wedge of objectivity might be to blame. You see, I had internalised the scientific imperative of non-involvement as the highest ethical standard, while performing the salto mortale to connect to plants, I had unwittingly amputated love, the tool perhaps most useful to achieve this, because western philosophy tells us empathy with plants is not possible and natural science confirms we are better off this way.

Špela Petrič. Courtesy of Miha Fras

You are participating in the 8th Inter-format Symposium on Rites & Terrabytes as well as in Summer Exhibition that will take place in late July-August at Nida Art Colony, Lithuania. First of all, knowing that you are still in the process, what is your experience while reflecting upon the given contexts of nature, culture, and identity of the Curonian Spit?

I arrived to Nida with a plan to develop the final piece of the Confronting Vegetal Otherness opus. Phytocracy would be a participatory performance during which we probe a particular area to map the ways in which plants govern people. The tools developed for this action would engage the participants in a kooky narrated experience of plants that emerges from an anarchic recombination of actual positions of governing bodies, stakeholders, ecological relations etc. Taking a closer look at the discourses relevant to plant-human relationship and specifically to the Curonian Spit was a necessary first step of my research.

Many texts have been written about Neringa as a (post)romantic, (post)modernist eden, a romantic symbol of the hard life “man-against-nature” turned elitist “kurort” (resort) and finally a national asset and source of pride, consolidated by the Unesco World Heritage Site status. The construction of the Curonian Spit as a myth-place, with a carefully selected and sometimes re-invented history, points to a struggle of establishing a national identity, which could be understood as a post-colonial process of emancipation from the Soviet but also German (Prussian) past (the recent resurgence of paganism in Lithuania also supports this). In relation to the environment (the curated nature), it is interesting to look at the governance of the Curonian Spit through the paradigm of “global nature”, which follows a North American model of wilderness, cultivating the image of a well-balanced, pristine ecosystem as a commodity (this view was promoted by Lithuanian president Valdas Adamkus, who in fact worked for the U.S. Environment Protection Agency). Global nature is deterritorialised in the sense that interests to maintain it often come from dislocated places. To the people living in the precious locales, biodiversity and wilderness become a paradoxical resource – how exactly is the exploitation supposed to take place if their value is derived precisely from the fact they are untouched (this antagonism is perhaps most apparent in the conflict between the Neringa Municipality (the local inhabitants), private investors and the National Park)? It seems that transnational economy and governance significantly inform the (non)utilisation of land, which is underscored by the collaboration between scientific institutions supporting the Spit’s status of a natural treasure (surveys of species, ecological research, dune protection) and economic interests (e.g. research results articulated as input for the management of ecosystem services). So it is important to keep in mind that while the turbulent history and intense landscape interventions on the Spit raise obvious questions of nature/culture and national identity, these might be significantly influenced by the overarching narrative of global neoliberalism.

Thank you, Špela, and best of luck in your future ventures!