KUMU is the first major museum in Estonia to host an exhibition about video games. “Let’s Play?! Computer Games from France and Germany” displays a selection limited to these two nations because the exhibit marks the 50th anniversary of the Élysée Treaty.

The curators, Andreas Lange (Computerspielmuseum Berlin) and Blandine Lebourg (Plaine Images), have done a good job when it comes to the selection of games. The visitor can see and play games from an assortment of independent developers, some mainstream productions, and a few experimental art games.

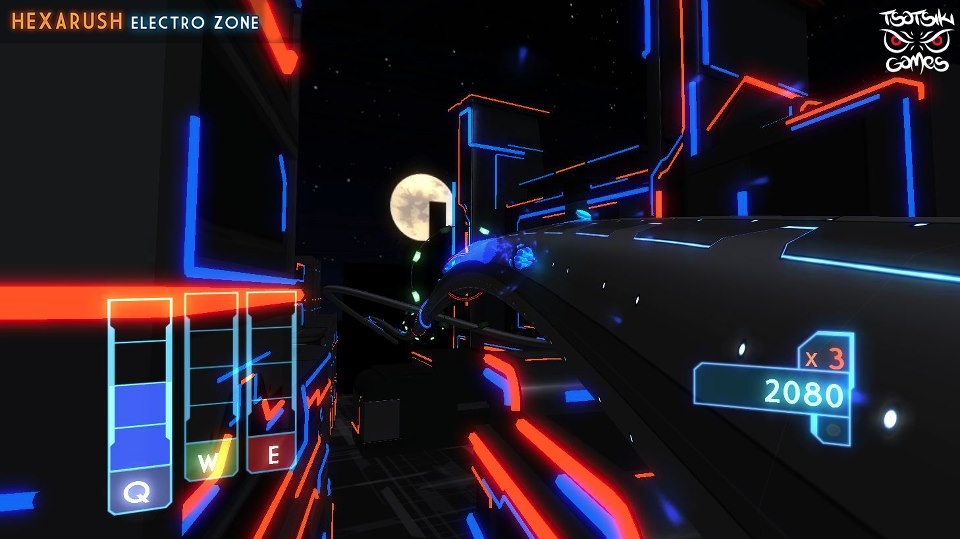

Concerning genres, exhibited are strategy games, puzzle games, role playing games, sports games, and a couple of educational serious games; the latter are made not only for entertainment but with the purpose of addressing some real world problem, and for educating the players (apropos, such games can also be used for advertising or propaganda). Conspicuously absent is one of the most popular of gaming genres, the first-person shooter. It can’t be that the curators did not find any worthwhile examples to include in their exhibition. For instance, the popular and critically acclaimed Crysis franchise (2007–), which is considered by many to be a technological marvel because of its impressive visuals, is developed by Crytek, a Frankfurt-based German game company. The reason for this absence, I conjecture, is that a genre where the player takes control of a disembodied hand gripping a gun, and proceeds to kill most things that move is simply not fitting for commemorating a treaty of friendship.

From a technological standpoint, the exhibition presents a variety of hardware and user interfaces. Visitors get a glimpse at the different ways in which players can interact with games. There is a marked prevalence of tablet and smartphone games. This reflects the shifting trends in the gaming market. Games development seems to be increasingly oriented towards portable devices, specifically smartphones and tablets, because this is a new untapped market.((Fong, Henry. 2013. Four must-read predictions about the Chinese game market in 2013. Gamasutra: The Art and Business of Making Games.Online: http://gamasutra.com/view/news/184803/)) ((Khaw, Cassandra. 2012. Mobile games taking big bites out of Nintendo, Sony’s handheld biz. Gamasutra: The Art and Business of Making Games.Online: http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/175905/)) Given the dropping sales numbers of high-end games produced for specific gaming hardware (consoles),((White, Martha C. 2013. Game Over? Why Video-Game-Console Sales Are Plummeting. Time, February 13. Online: http://business.time.com/2013/02/11/game-over-why-video-game-console-sales-are-plummeting/; Fritz, Ben. 2013. Sales of video game discs and consoles dropped 22% in 2012. Los Angeles Times, January 10. Online: http://articles.latimes.com/2013/jan/10/business/la-fi-ct-video-games-sales-20130111)) and the increasing costs of developing such games,((Campbell, Colin. 2012. AAA games: What lies ahead?. Gamasutra: The Art and Business of Making Games. Online: http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/174972/)) ((Brycer, Josh. 2012. Are AAA studios DOA?. Gamasutra: The Art and Business of Making Games. Online: http://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/JoshBycer/20121211/)) developers and investors are increasingly turning towards the tablet and smartphone markets in hopes of supplementing their falling revenues.((Merel, Tim. 2011. Global Video Games Investment: China, Online, Mobile Ascendent. Gamasutra: The Art and Business of Making Games. Online: http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/134664/. There are also predictions that gaming will increasingly migrate to portable devices: cf. Peterson, Steve. 2013. Mobile to be “primary hardware” for gaming by 2016. Gamesindustry International. Online: http://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2013-04-30-mobile-to-be-primary-hardware-for-gaming-by-2016)) The prevalence of such games in the exhibition can be seen as reflecting these changes.

The earliest institutional exhibitions of video games go back to the early 1980s when art museums began retrospective displays of then outdated first and second generation games. The Museum of Moving Image has shown video games ever since it opened in 1988, and in the end of 2012 it launched an exhibition titled “Spacewar! Video Games Blast Off.”((Suellentrop, Chris. 2012. A Dinosaur Gallery for Video Games. The New York Times, December 15, p. C1. Online: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/15/arts/video-games/spacewar-video-games-at-museum-of-the-moving-image.html?_r=1&)) This is just one of a slew of recent video game exhibitions in various museums across the world. The “Game Masters” exhibition at the Australian Center of Moving Image in 2012 focused on the game designer as auteur (currently the exhibition is touring internationally).((Kolan, Patch. 2012. Game Masters: From Miyamoto to Molyneux, Gaming’s Greatest Minds Under One Roof. IGN, June 27. Online: http://www.ign.com/articles/2012/06/28/game-masters-from-miyamoto-to-molyneux-gamings-greatest-minds-under-one-roof)) The Ontario Science center is hosting “Game On 2.0: An Exhibition” with more than 150 playable games spanning the more than 60 year history of the medium.((http://www.ontariosciencecentre.ca/gameon/)) “The Art of Video Games,” an exhibition seeking to explore the evolution of video games as an artistic medium, with a focus on visuals and creative uses of new technologies, opened in the Smithsonian American Museum in 2012,((http://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/archive/2012/games/)) travelled to the EMP Museum, ((http://www.empmuseum.org/at-the-museum/current-exhibits/the-art-of-video-games.aspx)) and will move on from there through the U.S.((Suellentrop, op. cit)) The exhibit featured 240 games, chosen partially via an online poll, which, some felt, made the show a bit too eclectic and predictable.((Salter, Anastasia. 2012. Playing Through the “Art of Video Games” Exhibit at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Journal of Digital Humanities,Vol. 1, No. 2. Online: http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/1-2/playing-through-the-art-of-video-games-exhibit-by-anastasia-salter/)) Finally, MoMa recently acquired 14 games, exhibited in the “Applied Design” show till January 2014,((http://www.moma.org/visit/calendar/exhibitions/1353)) for their planned collection of 40, as representatives of a new category of artworks in its collections.((Holpuch, Amanda. 2013. Video games level up in the art world with new MoMa exhibition. The Guardian, games blog: http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/gamesblog/2013/mar/01/video-games-art-moma-exhibition; http://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2012/11/29/video-games-14-in-the-collection-for-starters/))

In recent years, museums dedicated to the preservation and exhibition of video games have sprung up. In America there’s the International Center for the History of Electronic Games,((http://www.icheg.org/)) and the American Classical Arcade Museum,((http://www.classicarcademuseum.org/)) which covers the gaming industry from its inception in the early 20th century up to the 1980s economic crash of the arcade industry. In Germany, there is the Computerspielemuseum,((http://www.computerspielemuseum.de/1210_Home.htm)) which is also partly responsible for “Let’s Play?!” Established in 1997, it was the first institution ever to present a permanent exhibition centered on digital entertainment.

In March 2006, the French Minister of Culture characterized video games as cultural goods, as forms of “artistic expression,” and granted the French gaming industry a tax subsidy. He also introduced three game designers, Michel Ancel (responsible for the Rayman [1995–] franchise, and the cult hit Beyond Good & Evil [2003]), Frédérick Raynal (creator of the classical Alone in the Dark [1992–2008] and Little Big Adventure [1994, 1997] series), and Shigeru Miyamoto (the creator of some of the most successful video game franchises of all time, likeMario [1981–], Donkey Kong [1981–], and The Legend of Zelda [1986–]) into the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres as a sign of recognition for their contributions to the arts. This was both a symbolic and an economic move: symbolic, for it confers a kind of high cultural recognition on games; economic, because, as in the case of French cinema, the recognition of games as an art form makes the French gaming industry eligible for financial assistance.((Crampton, Thomas. 2006. For France, Video Games Are as Fruitful as Cinema. The New York Times, November 6. Online: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/06/business/worldbusiness/06game.html?adxnnl=1&adxnnlx=1367579175-Zh+w54L5lEu6Qh9Bq9sb+A)) Another landmark symbolic move came in May 2011 when the United States National Endowment for the Arts expanded the allowable projects applying for grants to include interactive games. Likewise, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in June 2011 that video games were protected speech, similarly to other forms of art.((Funk, Joe. 2011. Games Now Legally Considered an Art Form (in the USA). The Escapist. Online: http://www.escapistmagazine.com/news/view/109835-Games-Now-Legally-Considered-an-Art-Form-in-the-USA))

These and other developments have contributed to the view that at least some video games can, in some sense, be considered as art. However, not everyone agrees that games should be in an art museum.((For instance, Jonathan Jones, an art writer for The Guardian, argues that MoMa’s acquisition of games for its collection is part of a larger misperception that games are art. A work of art is supposed to be one person’s reaction to life, a personal vision, and any definition of art that does not include this dimension is worthless. Cf. Jones, Jonathan. 2012. Sorry MoMa, video games are not art. The Guardian, Jonathan Jones On Art Blog: http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2012/nov/30/moma-video-games-art)) The debate about whether video games are or are not art precedes and enframes the events I’ve just discussed. The whole problematic rose to public consciousness in the mid-2000s when the now departed film critic Roger Ebert stated that video games are a non-artistic medium. There are other critical opinions within the game industry as well, but I will only discuss Ebert’s views in order to give some idea of the critical arguments brought against games as art since many other naysayers have relied on similar arguments.

The crux of Ebert’s argument is that games require player choice and input, a strategy opposite to that employed by serious film and literature.((Ebert, Roger. 2005. Why Did the Chicken Cross the Genders? RogerEbert.com. Online: http://www.rogerebert.com/answer-man/why-did-the-chicken-cross-the-genders)) A work of art is created by an artist—it is an expression of its author’s intent and inner vision. If the public can interfere with or change the work, then they in effect become the authors. An audience is supposed to be led towards an inevitable outcome, not influence it by their actions.((Ebert, Roger. 2007. Games vs. Art: Ebert vs. Barker. RogerEbert.com. Online: http://www.rogerebert.com/rogers-journal/games-vs-art-ebert-vs-barker)) Furthermore, unlike works of art, games have goals, rules, and outcomes, including the possibility of winning or losing. A game without these characteristics is not a game anymore: art you can only experience, not win. This is a romanticist and mimetic or representational definition of art: art imitates nature, but also improves and alters it via the artist as a medium or intermediary.((Ebert, Roger. 2010. Video Games Can Never Be Art. RogerEbert.com. Online: http://www.rogerebert.com/rogers-journal/video-games-can-never-be-art)) To Ebert’s credit, he was consistent, and did not consider many of the films he reviewed to be art either—good entertainment, yes, but not high art.((Ebert, 2007, op. cit)) Basically the dispute is concerned with the definition of art. Instead of giving an overview of counterarguments, I’d like to tease out some problems with Ebert’s definition of art in order to show that it is too restrictive and excludes not only games but also many types of works that are generally considered to belong to high art.

The mimetic view of art is probably the oldest in Western aesthetics. It was first championed by both Plato((Cf. Plato. c. 380 BC. Republic, Books 2, 3, 10, in John M. Cooper (ed.). 1997. Plato: Complete Works. Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company)) and Aristotle.((Cf. Aristotle. c. 335 BC. Poetics, 1447a14-1447b29ff, in Jonathan Barnes (ed.). 1984. The Complete Works of Aristotle, Vol. 2. Princeton N.J.: Princeton University Press)) Both believed that all arts are involved in the imitation of nature, which is a necessary condition for something to be considered art. Looking back at the past century of art, it seems that this theory cannot be the whole truth regarding the matter. What does abstract expressionist painting imitate? Or what do decorative geometric patterns imitate? The mimetic view seems too narrow.

A modified version of the mimetic view is the representation view: a represents b if the sender intends a to stand for b and the audience realizes that a is intended to do so. While this view is broader, many works of art are still excluded. Consider architecture: a church does not stand for the house of God, it is a house of God. A neo-representationalist position—the necessary criterion for art is aboutness, semantic content that requires interpretation—is not a significant improvement either. A sad piece of music is not about sadness. Stating that a piece of music is sad amounts to describing a property that it has; a piece has slow tempo, it is not about having a slow tempo. Likewise, some decorative art is simply beautiful due to the composition of its parts. Such works are intended to work solely due to their perceptual impact on the viewer. Thus insistence on representation as a necessary criterion for something’s being art is at least problematic.

The second part of Ebert’s definition is in line with an expressivist view of art that is rooted in romanticism. A work of art expresses a point of view—the author’s feelings and emotions towards something. A corollary of this view is that art explores the subjective world of feeling. Hence it is somewhat parallel to science, albeit focused on a different realm. But much of art is focused on communicating or exploring ideas. For instance, a great deal of 20th century painting has been about the nature of painting. Artists dealing with impossible geometry invite us to reflect on the peculiarities of our visual system. Such works are cognitive, not emotive. And even if everything humans do is accompanied by some kind of emotion, traces of it need not be discernible in the objects produced. Just as I cannot determine the emotional state of the author of a scientific text, I need not be able to discern the emotional state of the creator of an artwork.

Finally, the assumption that an artwork requires an author becomes questionable if one considers examples like the Surrealist’s Exquisite Corpse, texts like the I Ching, Raymond Queneau’s Cent Mille Milliards de Poèmes(1961), or examples of hypertext fiction such as Michael Joyce’s Afternoon, a story (1990), Stuart Multhrop’sVictory Garden (1992), and Mark Amerika’s GRAMMATRON (1997). Such works have been called cybertexts due to their feedback-centered mechanical constitution. Literary theorist and game scholar Espen Aarseth has dubbed the corpus of such texts ergodic literature (ergon meaning “work” and hodos meaning “path” in Greek). Audiences are expected to directly manipulate such works which are based on a set of rules that generate sequences of symbols for interpretation.((Aarseth, Espen J. 1997. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 10, 1-4)) Much of contemporary technological art also puts the idea of authorship into question. For instance, Eduardo Kac requested that a French laboratory create a green-fluorescent rabbit implanted with a Green Fluorescent Protein gene from a type of jellyfish. The laboratory complied.(( Kac, Eduardo. 2000–. GFP Bunny. Online: http://www.ekac.org/gfpbunny.html)) Who is the author, Kac, the laboratory, or nature itself in some roundabout way? (I’m aware that postmodernism declared the author both dead and buried a while back. I’m not relying on this point here because I’m interested in finding actual examples instead of theoretical counterarguments.((Cf. Barthes, Roland. 1967. The Death of the Author, in Roland Barthes. 1977. Image Music Text, tr. Stephen Heath. London: Fontana Press, pp. 142-148)))

Examples like these show the limitations of representational and expressivist definitions of art that many critics besides Ebert rely on. Yet such cases cannot hope to settle the debate since many of them belong on the fringes of literature and art, and were often knowingly composed to challenge established notions of art and authorship. Furthermore, the line between games and works of interactive art or storytelling is not at all clear. It should be noted that in his later years Ebert recanted somewhat, claiming that games can be considered art in a non-traditional sense.((Ebert, Roger. 2010. Okay, Kids, Play on My Lawn. RogerEbert.com. Online: http://www.rogerebert.com/rogers-journal/okay-kids-play-on-my-lawn))

The reason I’ve discussed this debate at length is that when situated within its framework, the KUMU exhibition implicitly communicates a position similar to the critics of the potential art status of games. This becomes apparent when one focuses on where the games are being displayed. The “Let’s Play?!” exhibition is relegated to KUMUs foyer, next to the coatroom, ticket booth, and museum shop. Social spaces can be conceived of as socially constructed complexes which affect spatial practices and perceptions. Many social spaces are given rhythm by the gestures which are produced in them, while the spaces, in turn, are also producing the appropriate gestures. The everyday gestural realm generates its own spaces, and these valorize certain kinds of practices above others. This gives rise to discourses related to a given space, which generate conventions and consensus prescribing its proper use and etiquette.((Henri Lefebvre. [1974] 1991. The Production of Space, tr. Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 49-52, 55-57, 216-217)) Conventionally, exhibition spaces and galleries are meant for contemplative lingering; the viewer is expected to stop in front of the works on display, take time to experience them, and to meditate. On the other hand, the foyer, like the corridor, is conventionally meant for passing through, for speedy traversal towards some destination, or short-term resting at best. (We get annoyed or suspicious when someone lolls about or saunters in our way in corridors and foyers. Similarly, when someone breezes through the gallery, we tend to think that they were either being superficial or not really interested in the exhibit at all.) Hence within a gallery or a museum, the exhibition space has a higher status in comparison to a corridor or a foyer. Because of this, works displayed within a gallery acquire the status of art, a certain gravitas and a higher value. We as viewers presume this to be the case because they were chosen to be there by those, viz. the curators and critics, with the symbolic power of assigning to or withholding from an object the status of art.((Cf. Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 76-80)) Even when we encounter things in the gallery, which we would not consider to be art, because they are within the gallery (or some other legitimized institutional setting), our first reaction is usually to doubt our own initial judgment instead of adhering to it. Objects exhibited outside the gallery do not partake of this privilege.

Games in KUMU are consigned to a space outside the gallery. On the other hand, concept art from well-known works of Japanese animation is shown in the 4th floor B-wing exhibition space. Both video games and anime are instances of pop culture entertainment that have been, and in some cases still are, considered to be of questionable cultural merit. Furthermore, both were, and to some extent still are, the hallmarks of subcultures that are not yet completely infused with the mainstream. Yet anime concept art, which fits more comfortably under existing and established definitions of art, is shown within a gallery space, while games—the art status of which is ambiguous in light of popular definitions—are shown outside, near the museum door, as if to be passed over quickly or to serve as a distraction for children. Hence it seems that KUMU is following the conservative side of the “are games art?” debate. In comparison to MoMa and the Smithsonian, for instance, where games are exhibited inside a gallery, KUMU is playing it safe. This is a shame.

The exhibition is on view at KUMU Art Museum (Weizenbergi 34 / Valge 1, Tallinn) from April 5 to June 30, 2013. For more information see “Let’s Play?! Computer Games from France and Germany”

Exhibition view

Exhibition view

Summer Stars

Pudding

Anno 2070

Trauma

Hexarush