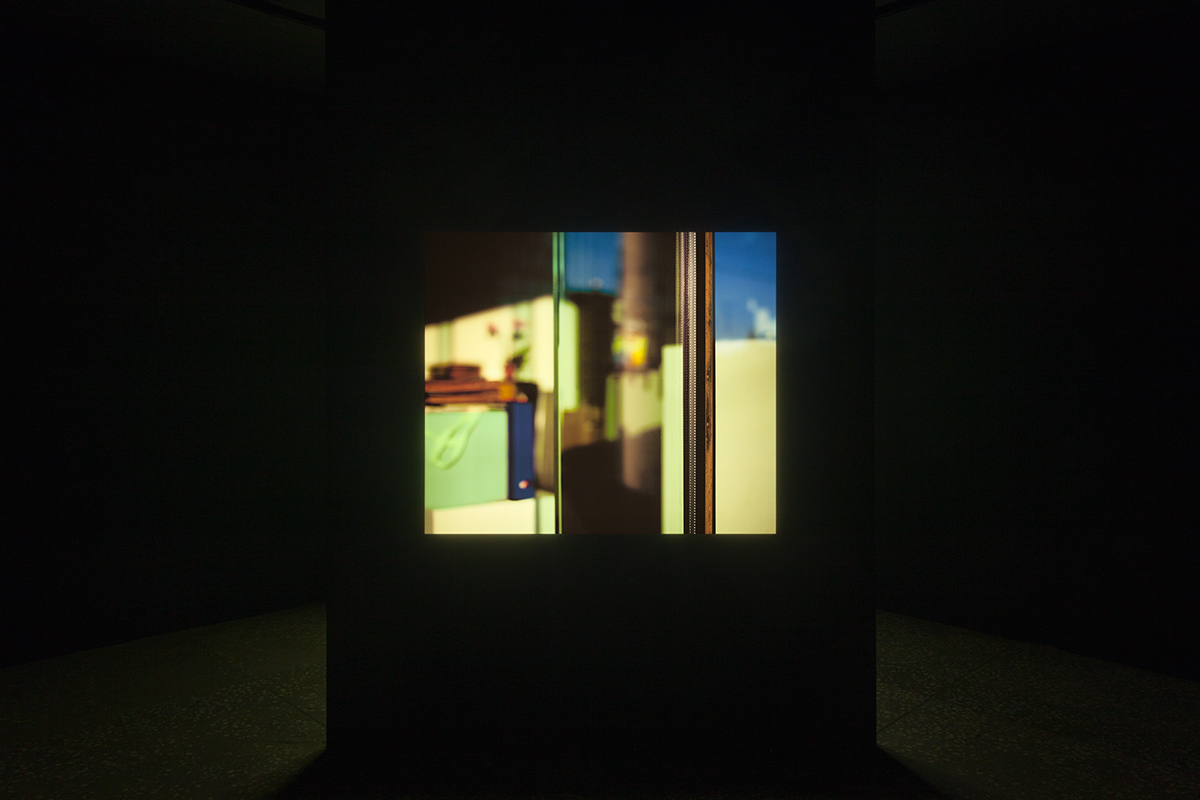

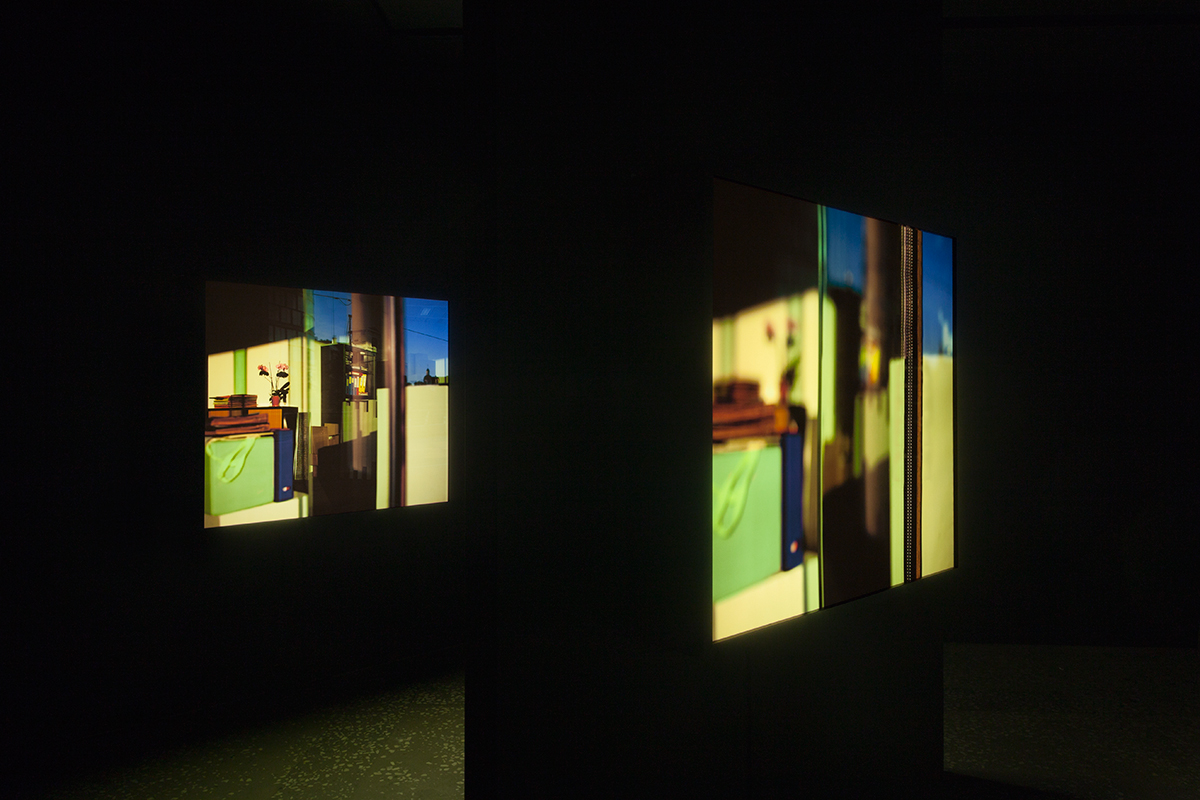

Anyone tired of ‘white cube’ spaces will be delighted to step into the darkness of Paul Kuimet’s solo exhibition Late Afternoon, currently on display at Tallinn City Gallery. The show has a minimalistic built up structure which quickly hides the viewer behind its heavy silky curtains in the cinema-like blackness. What the white cube accentuates, Kuimet’s ‘black cube’ makes disappear. It is radically different from the ‘museum without the walls’ principle by French surrealist, novelist, and art theorist Andre Malraux, which puts the viewer in the spotlight together with the artworks exhibited. Paul Kuimet’s use of the black cube offers anonymity and seclusion; the very moment a visitor finds their way through the soft, but heavy, theatrical wall of fabric, they leave the side of the audience behind to become part of another reality, entering the artist’s viewpoint and can no longer be seen as part of the audience anymore. Unlike traditional cinema that paralyses its audience by handcuffing them into comfortable cinema-chairs, Kuimet resists from restraining visitors of their movements, but instead forces them to be active in a room full of darkness where the only visible thing in the photographic installation is a light-box. Visitors become like moths finding their way towards the light, continually ‘dancing around’ the still images until they seem to start moving. Each visitor ends up creating unique moving images of Kuimet’s still life every time they enter or reenter from the other side of the curtain. This way every photographic installation also becomes a spatial one, dramaturgically creating as many Late Afternoon experiences as there are visits.

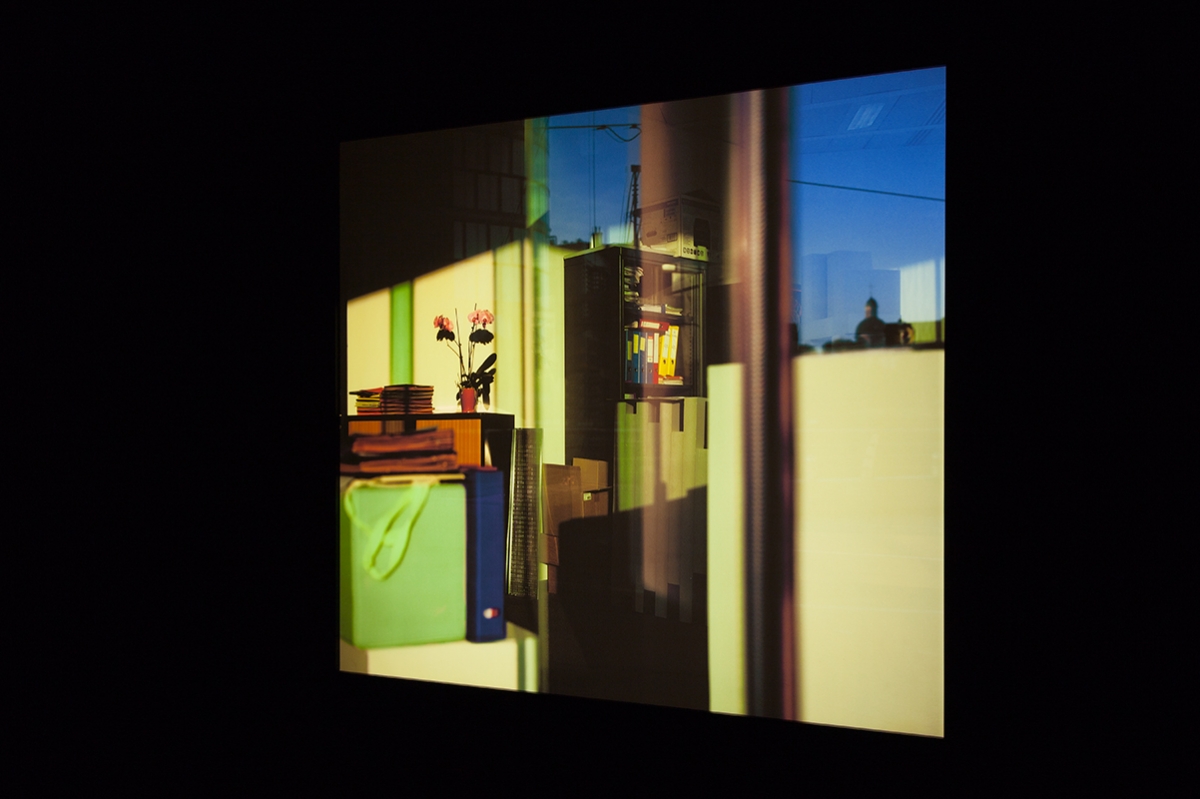

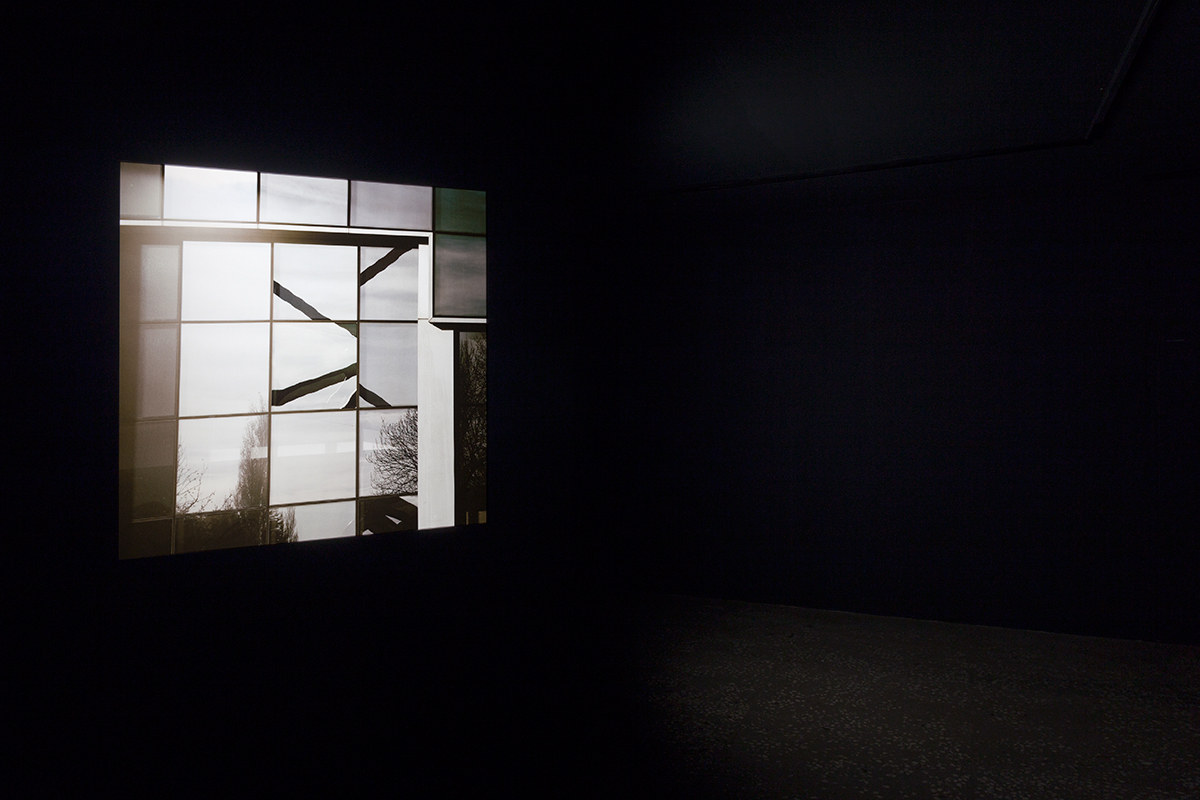

Late Afternoon is divided into three parts, two of which, Late Afternoon and Perspective Study, each consist of two architectural photographic installations, with the third part Still Life being a 16 mm analogue film projection. All parts contain medium-reflective pieces. The images and the technology used to produce them are of equal importance. If one takes time to wait, there comes the understanding that all three works are actually emphasising the subjectivity of motion and statics. Paul Kuimet makes his audience pay attention to the casual things which tend to go unnoticed. At the same time he changes one’s understanding of the difference between film and photograph, movement and stillness. One can even say that his photographic installations are about movement and the 16 mm film really represents stillness. Late Afternoon shows that movement and non-movement are not dissimilar after all, and that actually there is no stillness whereby it could all just be a play of the mind – the way you look, when you look, from where you look and how long you look. Playing with the space and time, Kuimet takes away the naturalness of linear perspective – there is no longer pre-approved ‘correct’ points of view, but endless valid possibilities to explore the perspective without any fear of disapproval – so no-one (not even the gallery worker) can see the viewers gaze within Kuimet’s black cube of darkness.

There is an idiom in Estonian language about the ‘greyness’ of everyday life, where everything around seems to melt into a boring monochrome non-place called the ‘everyday’. This colourless world has no movement or unique features, just one and the same perspective each day … every day. Late Afternoon, with its classic office interior and architectural motifs, illuminates our consciousness to this nothingness using flashes of somethingness to force us to see what we have forgotten to notice, the exhibition becomes a laboratory where exhibits interact as a ‘mathematical proof’ that unique colours, details and motion do exist in everyday space-time. By making the statics disappear Kuimet’s exhibition turns the everyday non-space into a space taking us from nothingness into the desired state of being something. Isn’t this quality something to be grateful for?

In the basis of understanding Paul Kuimet’s choice of media should be a theory that photography itself is a language. Everybody can take great pictures, but will they form sentences and ideas? Kuimet’s clean lines, minimalism and fascination with architecture have been refined having studied film and photography at universities in Tallinn (Baltic Film and Media School & Estonian Academy of Arts), London (University of East London) and Helsinki (University of Art and Design Helsinki – TaiK). Kuimet has also taken up artist residencies in Italy, Brussels and Austria. Kuimet is one of the first contemporary Estonian artists who dared to start researching the early 21st century socio-cultural context in Estonia. His first solo exhibition in 2010 at the Hobusepea Gallery in Tallinn showed his photo series In Vicinity. Referring to an earlier photo series by Dan Graham, he drew an honest visualisation, taking a closer look at the not-so-perfect architectural and spatial policies of Tallinn’s recent developments – at that time idealistically viewed, oh-so-popular countryside-suburbias, where cowboy-like desire to own a piece of land resulted lifeless patterns of densely adjoined ‘dollhouses’ without desired privacy and lifestyle. In 2013, Kuimet made it to the Kumu Art Museum, where he exhibited 38 framed silver gelatine prints on aluminium composite called Notes on Space. The photo series consisted of selected photographs from the section of catalogued monumental paintings in Estonia from the book Notes on Space. Kuimet’s series focused on photography’s failure to represent the grand murals of the Soviet state and acted as an example that there is no ‘one-size-fits-all system’.

Daniel C. Blight has written in his essay called Underneath about Notes on Space: “We can see them, imbued with history and nostalgia, but in doing so we choose not to see something else, perhaps because it sits outside of the language of representation with which we are familiar.”[1] I guess what Blight means is that in the 21st century we cannot keep adding new dispositions to the existing curriculum, but need a completely new system and mindset. Hanno Soans[2] has picked keywords such as ‘systematisation’ and ‘pictorial perfection’ to describe the artistic techniques of Paul Kuimet. Although Kuimet often uses video as his artistic media he considers himself mostly a photographer and names artists like Stephen Shore and Robert Adams as his main influences. Kuimet shares Shore’s Andy-like (Warhol) aesthetic emptiness and like Adams is concerned with moments of regional transition and does not fail to see the beauty of the everyday. But there is definitely more in that the characteristic that we might call systematisation also gives Kuimet’s images this perfect mathematical look of an architectural drawing.

Photography by Paul Kuimet

________________________

Previously exhibited in Brussels (between 13th April to 5th June 2016), LATE AFTERNOON is on display at the Tallinn City Gallery from 18th of June and 24th July 2016. The exhibition has been organised within the framework of the residency exchange programme between the Estonian Union of Photography Artists and Brussel’s Space Photographique Contretype.

Paul Kuimet is the recipient of various prestigious awards like the Wiiralt Scholarship (2011) and the Sadolin Art Prize (2012). Recent exhibitions include The Baltic Pavillion, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania at the 15th International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia (2016), Espace Photographic Contretype (Brussels, 2016), Kohatu. CAME travelling exhibition (2015-2016), From Explosion to Expanse (Tartu Art Museum, 2015) and Black House. Notes on Architecture (CAME, 2014).

[1] The text is published on the occasion of the exhibition Notes on Space. Photos by Paul Kuimet at Kumu Art Museum (Tallinn, Estonia), 10.10.2013–05.01.2014.

[2] The essay is published in the catalogue of the nominees of Köler Prize 2013. Published by Lugemik & EKKM, 2013, ISBN 978-9949-9391-3-8