Emilija Škarnulytė. Photography: Peter Rosemann

The eyes are trying to cover glaciers in the Arctic Circle. The ears are catching quasar sounds. Dark waters are stirred by a hypnotizing creature. The head is dazzled by unimaginable industrial structures. Ultimately sounds come together with waves, images are pulled into the space of thousands of soft bulbs, into the world of the past and the world of the future. This is only a part of Emilija Škarnulytė (b. 1987) work. Emilija is a filmmaker, a visual artist who studied sculpture at Brera University in Milan, and later took an MA in contemporary art studies at the Tromsø Academy of Contemporary Art in Norway. Her works have been presented at the Venice Architecture Biennale, in Bolivian SIART, São Paulo and Riga Art Biennales, the International Rotterdam Film Festival, the Pompidou Film Festival Hors Pistes, in The International Short Film Festival in Oberhausen, and many other venues. In 2018, her work could be seen in London, Berlin, San Francisco, Houston, Reykjavik, Brest, Busan. In 2009, Emilija Škarnulytė was awarded the MIUR – National Italian Award, in 2015 the Anne and Jakob Weidemanns Award, the Young Artist Award in Oslo in 2016, and in 2017 she won the Cinema der Kunst Project in Munich. This interview with Emilija covers archaeology of the future, hyperobjects, climate, economic and social change.

Emilija, when I started writing, I wondered for a long time which city could be your place of residence, because just in the last month you have been in six countries. Where is your current creative base?

Last year was most constant place-wise, when I performed a yearlong residence at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin. I recently changed my bio, and wrote that I work nomadically. First, I used to live in a triangle between Lithuania, Berlin and Norway; but then projects in Korea and Texas came up … For ten years I have been working like this, and my locality dictates scenarios and mythologies. I have realized that I am not a studio artist; I need to be in the place and get to know surroundings where the action takes place. It is an archaeological, geological research. Those are the professions I dreamt of when I was a child. From a very young age, I was interested in invisible structures, just as now I am interested in the invisible structures of mines, as in direct invisibility (blindness) in my film Aldona.

Emilija Škarnulytė. Photography by artist

What projects are you currently engaged on?

I have two exhibitions in Texas. One is a group project Hyperobjects (term Hyperobjects is coined by professor of literature and the environment Timothy Morton) at the Ballroom Marfa Art Center, curated by Timothy Morton and Laura Copelin. It features my movie Sirenomelia. Another exhibition ‘The Future is Certain; It’s the Past which is Unpredictable’, curated by Monika Lipšić, is now under way at the Blaffer Art Museum. In Berlin’s Planetarium, London’s Bold Tendencies, Riga Art Biennial (RIBOCA) I presented Mirror Matter, in Brest I am participating in ‘Directing the Real: Artists’ Film and Video in the 2010s’, in the Passerelle Center of Contemporary Art, where I am showing Sirenomelia. In the future, the KOSMICA Festival organized by Arts Catalyst in London and the Reykjavik Arts Festival await in a second half of June.

The 360 video projection Mirror Matter, presented at the Berlin Planetarium, is a part of the DOME space exploration project; while presenting Bold Tendencies you invited people to climb on to the roof and listen to black holes. Are your ongoing projects are aiming to cosmic topics?

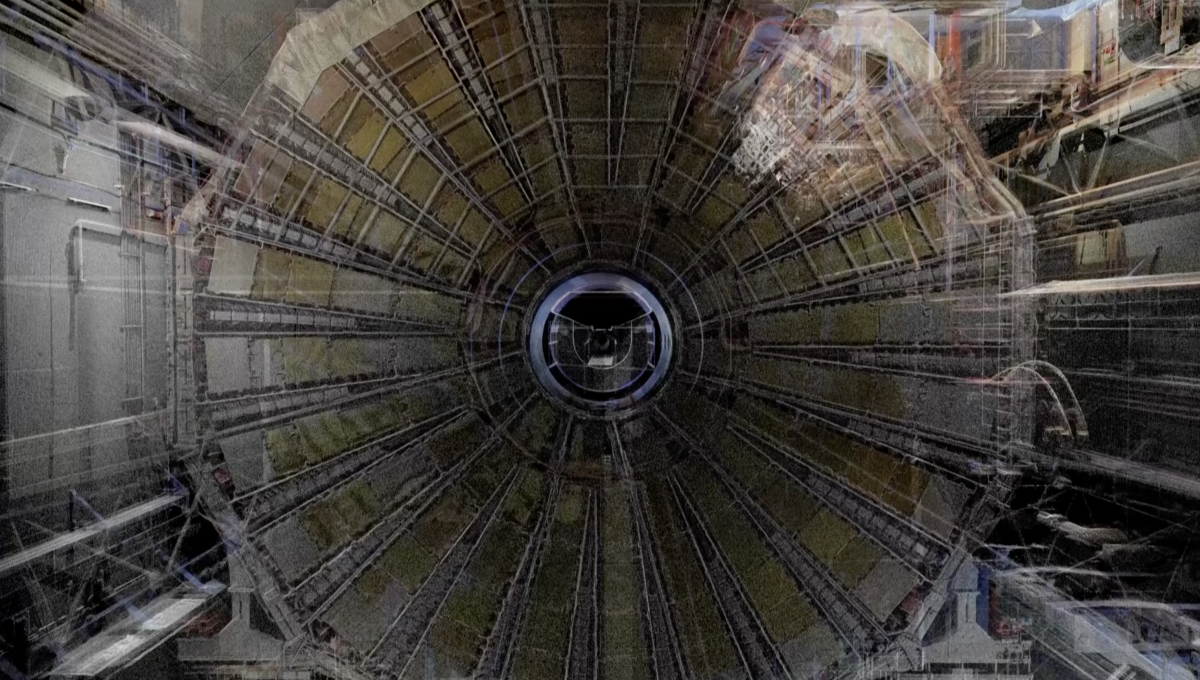

These projects are going and aiming entirely for space exploration. Mirror Matter tells about the Neutrino Observatory in Japan, which was built in 1980-ies. Why build an observatory at a depth of one kilometer? The geometric stratum of electrons and protons cannot travel through geographic strata, but neutrino pierces the Earth’s layers easily, and, once reaches the observatory with 13,000 mirrors installed, neutrino reflects itself. Each of the mirrors is a light detector. In this way, scientists are trying to explore and answer what constitutes 95% of our universe, and neutrinos could provide the answers. As the observatory has stopped working, I created a 3D model of the lighting, construction and even the forms of the bulbs from the architectural drawings, the blueprints of the site.

I do not put my video works on monitors, but present them as large-scale installations, to allow an observer to enter, wander around, and receive a sensory experience. I am interested in physical experience, measurements, human and non-human scales.

Mirror Matter, video by Emilija Škarnulytė, in Kunstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, 2017. Photography: David Brandt

Mirror Matter, video by Emilija Škarnulytė, in Kunstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, 2017.

Tromsø in Norway, where you studied at the Academy of Contemporary Art, is the northernmost city in the world having a university and a botanic garden. On the outskirts of the city there are endless white expanses where nature reigns, and in other places industrialization, which works together with the exploitation of northern resources. You founded Polar Film Lab in this city.

It is true, after a few minutes walk outside the city, if you are lucky, you can find herds of reindeer. Basically, I feel at home in the city, people are close to each other. Tromsø is a city of Sami people, who are reindeer herders; and both languages, Sami and Norwegian, are used there. The academy was founded as a Sami art establishment as well. The city is active, and by the way, it is also the Norwegian techno music capital, where Royksopp and Bioshpere originated. The city hosts the Insomnia Electronic Music Festival, which is closely linked to the Berlin music scene. The Academy offered a very attractive programme, related to expeditions, landscape architecture and politics, and exploitation of resources. Then I also started to work with Tanya Busse, and we have continued taking on projects together.

The idea of Polar Film Lab was born during my studies. One of the largest international film festivals in Norway happens in Tromsø, but they do not have many experimental or short movies. So it was a niche and a need that could be filled with so many creative people in the city, and several spaces to do it. Polar Film Lab is a non-profit laboratory, at the moment runned by me and Sarah Schipschack, where we organize screenings, invite people from different countries, such as Australia, Japan and Palestine, to present their movies, organize creative workshops, and educate people. All on 16mm film.

Tromsø is a place where polar expeditions used to depart from, and one of the largest polar research centers was founded in the city. On each expedition, a cinema was installed on a boat: at that time Super8/16mm film was used in order to film expeditions, and the material immediately needed to be reviewed. It was a floating cinema laboratory. All those films have been scanned, it is a huge archive. Firstly, I wanted to make a laboratory on a boat and let it wander in the fjords … but we’ll see.

Did this place provide different inspirations?

The academy had an interesting landscape architecture programme that explored the northern region beyond the Arctic Circle. This is how the project started with Tanya, after seeing perforated maps of Scandinavian landmarks. The entire landscape of the ocean: just dots, with even more mines planned and already approved – carbon, iron, silver … The perforated landscape also brought up the topics of contemporary Sami political and economic situation. Tromsø is a place where global warming and geopolitical change could be clearly seen and observed: for example, the Northeast Passage has opened, so now Chinese cargo ships sail across the North.

Does Norway no longer seem like a large fluffy bunny?

I always imagined Norway as an idyllic and eco-friendly country, but I have noticed a lot of hidden economic and political structures. In the countryside, mining waste is thrown straight into the fjords, which you would not expect. People protest, but this does not change the situation. It is also very easy for foreign countries to obtain permits to mine in Norway, and these minerals are later simply shipped abroad, and it is difficult to understand why. Also, mines are much more toxic than oil wells, because strong chemicals have been used since the 18th century, and they are not being replaced. The whole area and the surrounding waters are immediately contaminated by these toxic materials.

Hollow Earth, 2013, 22 min. (Together with Tanya Busse). Manifold, Decad, Berlin, 2017. Photography: Julija Goyd

You have recently been to the Spitsbergen. Regarding the Hollow Earth installation (2013) which you created together with Tanya Busse, you stated that this work reflects the changing landscape of the North, which is cultivated by technology, and where ‘violence, desire, greed and emotions are played out.’ Technologies that exploit and explore the Earth’s resources also change the perception of space: all newly discovered layers of the sea, the earth’s surface, are opened up to the eye of the observer, previously not noted. In the installation, you correlated open layers of the Earth with the inside of the person, his emotions. Do you observe the same things now? Is the documentary about spatial projection, where man himself is not present, is a documentary about mankind?

Hollow Earth started on the island of Spitsbergen, where the mountains are like from a postcard, but inside they are empty. This is a chameleon mining technique, because only the shell of the mountain is left, but with supportive columns inside. Another mine is the size of Oslo, but it is not visible because it is in a hollow mountain. In Norway, the study of geology prepares specialists to focus only on the exploitation of oil, there’s no science of land, only how to find and dig up oil.

At the beginning, the project was an observation, now it is changing and aiming more at global phenomena. I am interested in looking at it from different perspectives, talking to mine workers, Sami people. My work poses indirect questions. It could be seen as an archaeological expedition into the future, often into inaccessible places: closed empty nuclear reactors, submarine bases, power plants, mines. These places have no humans, there are only artefacts and remains left. Indirect questions are raised, analyzing human activity and invisible structures, trying to make them visible, though not through political activism, but on the basis of mythology. I watch the greed of a human. I see the space-the landscape- the scenery more as a body with scars left by man, trying to put myself into the perspective of the future. Like Energy Island, in Hollow Earth there are no narratives, nor humans or characters. The geological structure remains, observing one stratum of the Earth after another, starting with aerial shots, approaching the ground, going underground, and moving to a microscopic level. It is an inner cross-section of the modern world, opening and flooding with the topics of human violence, desire, greed. These topics are relevant in No Place Rising as well.

In No Place Rising (2017) there is a striking element, a mermaid, a lonely creature that smashes the blue depths between the infinite fjords in a former Norwegian military and NATO submarine base. A mermaid is a mythical being with the qualities of humans and fish, thus linking land and water. Do you use it as a symbol, or as an effective visual solution?

It used to be one of the most important NATO bases, located 20 kilometers from Tromsø, which was recently sold. We wanted to buy it together with Tromsø Academy and hold techno music festivals. Submarine warships used to moor in the base, and when I first entered it, I wished to make a sports performance, to cross it swimming. Mythology topic appeared after talking with generals about their dangerous missions during the Cold War; and what the West believes about the East, and vice versa, or Korea, its North and South. I have always been interested in tense frontier zones and their research.

Then I thought that talking about Cold War mythology should be done from a mermaid’s point of view. No Place Rising sees everything through her eyes. She is not a stereotypical Mermaid. She is hairless, a woman-torpedo, or perhaps not necessarily a woman, perhaps transgender, but more a new species that have adapted to live in different conditions when there are possibly no people left. She is lonely and sensitive. The space around her is gigantic, aggressive and masculine, the same as in most projects: CERN, mines, underwater stations, and the world of astronomy.

Sirenomelia, 2018, by Emilija Škarnulytė at It’s the Past Which Is Unpredictable, Blaffer Art Museum, Houston, Texas

Does the topic of feminism also emerge in this context?

Recently, yes. If it is a perspective from a future archaeologist landing on the Earth and observing the scars that humans left, so whose perspective is it? Is it hers, or his, or whose? I am currently trying to work out from what perspective it is being looked at. Maybe it is an artificial intelligence archaeologist?

I am afraid not only that all constructions and spaces created are masculine. Most people are discussing the problem of human and artificial intelligence, but nobody talks about artificial intelligence programmed by men, and artificial intelligence programmed by women. In Silicon Valley, and elsewhere, there is a strong male domination, and artificial intelligence will absorb and change a lot of things soon, but who programmed it? Will we go back to the Middle Ages? Because programming is the language of the future, and those who have no access to it have no language.

Space is formed and changed by people, by combining and using it for their own use. Climate change, mass production, consumerism, lack of sustainability: these processes create an environment that manifests the existence of ‘only now’, often embracing humans as the rulers of space. These topics are also presented in your documentary films, talking about the current use of resources, going beyond social class, the boundaries of countries. For you, the idea of a peaceful Earth and reconciliation between humans and nature is important. Is this idea documented and left for the viewer to interpret, or is it documented as a state?

It is an observation, an attempt to convey a message and try to guide; but I do not want it to be activism projects. All the interviews, topics, opinions and questions arising are interwoven separately in publications; and in the actual creative work, I want to leave a lot of time to the viewer for meditation, to feel and weigh the scale, the time, the archaeological section, the timescales. This is important for me. Is it called a passive story? I do not think so; I am giving more freedom for interpretation.

In 2016, the Baltic Pavilion of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia participated in the Venice Architecture Biennale. They chose to describe the histories of the three countries, their development, spatial structures and material objects, by using the concept of a geological period, the Anthropocene, in order to reveal the interrelations, interactions and different interpretations of phenomena. Your documentary film Energy Island was shown in the Baltic Pavilion, depicting the last moments of the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant.

I was very pleased to participate. Energy Island was created from my movies research material, at that time I was working with a project – the topics of the curators of Baltic Pavilion coincided with my field of interest. In Energy Island there is a Sisyphean time, compressed and stationary. There is an important topic in it: the atom comes from the mines, from the ground, and is then buried again – atom returns to the ground, but only much more dangerous after the human touch. Uranium will last for only the next 80 years, so nuclear power plants will have to be closed, and then all of Europe will become a repository for hyperobjects. Sweden is burying nuclear plants in the Baltic Sea, because, as they state, it is one of the safest ways. New industrial repositories are being created.

So like Hollow Earth, Mermaid, Energy Island and Mirror Matter, these are locations as reflections of human activity, scars that have been left. If we find Neutrino observatory in Japan or CERN after 10,000 years, I could imagine them to be like cathedrals, if we look at them from a futuristic archaeological perspective. This is my attempt to create mythology for hyper-objects in the future from today’s perspective. But it is not easy.

You mentioned that you observe the environment from future projections. If we descend to a dream after a few hundred years, what kind of future do you see on the Earth?

I think about it every day. From those aerial shots, Hollow Earth and Mirror Matter, I started using expanded cinema narrative to convey the future perspective of a new cinematic language. You cannot always use a 2D camera, and it is no longer interesting to me just to document the world around. For me, what is most attractive is what is hiding behind politics: feelings, emotions, aspirations. Now I use Lidar scanning technology, a laser used in architecture, mines, which is a surveying method that measures distance to a target by illuminating the target with pulsed laser light and measuring the reflected pulses with a sensor. Lidar scans are 3D models, where you can travel through space and design corners with a camera. Lidar technology helps me to create a sense of the future and perspective, just like you could travel through architecture, flying particles. I like to work with this ‘language’, because if we try to define the future, I imagine all these industries overgrown, forming new kinds of symbiosis and species. I see CERN as an enclosed cave, with stalactites and albino alligators, I imagine all these industrial objects becoming part of geological stratum. Science, understanding of ourselves and of the world are changing rapidly: four dimensions are changed to six, six dimensions are changed to eleven, this statement is changed by saying that eleven dimensions are only a theory … That is how I imagine CERN – it is already in a geological stratum and if founded in the post factum, we (future archaeologists) would speculate: what is it, what was here, whether it was devoted to transcendental world, for what reasons was it built, who built it? Similar to the questions that are now being raised about the Egyptian pyramids. This is the future archaeology.

Mirror matter, 2017, video, 12 min. By Emilija Škarnulytė.

Mirror Matter, video by Emilija Škarnulytė, Hyperobjects in Ballroom Marfa, Mafra, Texas, 2017. Photography: Alex Marks