Due to the occasion of its 10th anniversary, Kaunas Biennial featured a “star curator” Nicolas Bourriaud who was expected to turn it into an exceptional and memorable event. Apparently this aim was achieved because visitors from both Vilnius and Kaunas had a chance to experience themselves a bit like foreign tourists coming to another country—the former because of the new “scenography,” and the latter because of the influx of “new faces.” Obviously, the presence of Bourriaud was a surprise to everyone. Driven by curiosity, we took the occasion to enquire about the curatorial practice, concepts and motivations of the author of The Radicant and Relational Aesthetics. The conversation touched upon a variety of topics such as critique of postmodernity, roles of artists and curators, the problem of representation, abolition of distance, and loss of uprootedness. It is important to note that all the inconsistencies, polemic points and miscommunications that punctuate this conversation are just as crucial as the ideas it touches upon. The discussion is a part of a more general enquiry by Echo Gone Wrong into how artists find themselves within the pre-articulated contexts brought by curators. What ideas and ideologies can we find behind the contemporary curatorial practices?

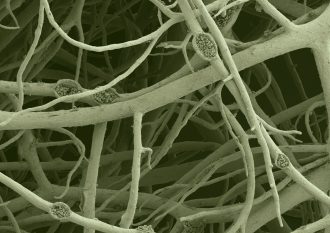

The conversation with Nicolas Bourriaud took place in August 2015, more than a month before the opening of the Kaunas Biennial. We met him in a dysfunctional Post Office building the empty rooms of which were yet to be filled with art. As a guest curator, Bourriaud was working on Threads: A Phantasmagoria About Distance, which was one of the main shows of the Biennial.

Nicolas Bourriaud — curator

Gintarė Matulaitytė — editor (Echo Gone Wrong)

Tomas Čiučelis — philosophy researcher (University of Dundee)

I

the radicant • the end of postmodernity • altermodernity •

looking for the ‘newness’ • leaving for the desert

Tomas: The particularities of your exhibition are still not clear yet, so we will probably have to see the exhibition in order to talk about the exhibition. Meanwhile, what is interesting now is those fascinating ideas that move and inspire your readers. I suppose you‘ve been asked about them a lot, you explained these ideas many times. Every time is like a repetition.

Nicolas: That‘s not a problem because you never say exact same things.

Tomas: That‘s true. Do you feel like your answers change every time, is there a sort of a development?

Nicolas: It‘s like a system of thought. Whatever it is, it‘s like a human brain, you know—it creates new connections all the time. Things evolve slowly, this is how things are. So it‘s impossible to repeat the same idea exactly the same way, you have to consider it from a different angle sometimes and the questions might be different, but it allows you to express the same idea from a different point of view. It shows that ideas are alive, otherwise ideas that could be seen only from one point of view, might be already dead.

Gintarė: Considering that The Radicant was released in 2009, could you say that the ideas like ‘radicant‘ and ‘altermodern’ went through an evolution?

N: Yes, these are distinct notions, I would say. Altermodern was an attempt to create a bridge from what proves to be a kind of dead-end: postmodernism is a dead-end for me, and the idea was to create a word as a key to actually get out of it. So, Altermodern is an attempt to pass from this prefix ‘post’ to another prefix that would allow new ideas to emerge.

Radicant has a totally different function, actually. It functions differently as a concept, because it is actually clearly linked to the vision of modernism and modernity. I would prefer modernity, actually, because ‘modern’ means belonging to the present. That’s the original meaning of the term. ‘Modern’ is modernus in Latin. So it‘s exact synonymous of contemporary, but it has been used to qualify a period of time; and also a set of values, concepts, and attitudes, which were characteristic of this specific period. So the prefix ‘alter’ was intended to open up a situation—one of connections and not one of progress, like in modernism, or that kind of permanent combination of past like postmodernism was. And I say “was” because for me it is over.

T: This is interesting. So in way you see modernity as a certain mode that can be repeated. The way it can be revived now is not in it‘s historical mode, or shall we say, not as a historical motive.

N: …but more like an attitude or behaviour, an attitude towards the present; I like this passage from Peter Sloterdijk’s book on Derrida where he talks about an exile from Egypt.

T: Yes, Peter Sloterdijk’s Derrida The Egyptian.

N: It is about leaving the bureaucratic Egypt behind: the pyramids, the priests, etc. Leaving this apparatus behind and going into a desert for me is the most accurate definition of modernism, of being ‘modern’ I would say. Because –ism is not the right term, being ‘modern’ is to leave big architectural institutions behind you and leave everything to find something new, actually. There is a verse by Baudellaire which is great: “diving into the unknown to find some newness.“

T: But what does it mean to be concerned with today, with the time of now, or with the moment of ‘now,’ with ‘nowness’? You use this metaphor of leaving the construct, the town, leaving the bureaucracy and everything [N: It‘s the main pattern]. But this gesture of leaving—isn‘t it in a way a refusal to deal with the situation instead?

N: I think it would be more like going away from the rarified and petrified forms of our ‘now’ and being able to acquire the new flexibility for the mind. I think that‘s the meaning of the exile out of Egypt.

T: So the gesture of moving away is important.

N: Moving away and trying to find a kind of a desert. It is interesting that in contemporary philosophy, for example, the pattern, the image of the desert is very present, actually. Althusser was saying that you have to create a void in order to access any kind of new. And it‘s something you can find in Slavoj Žižek also—it’s his “The Desert of the Real.” It‘s coming from Althusser for me, actually. So it‘s not random, it‘s not accidental that the motive of the desert is becoming more and more present, because the desert is the rarest thing today: a place where there is nothing.

T: But what do you think is happening in the desert with the subject?

N: That’s the big issue. It‘s interesting to see what happened historically in desert during the exodus, for example, if we come back to this original scene. Because walking, hearing voices, dealing with a few elements, like a bush or… [T: …phantasms…] …yes, phantasms and recreations of new values, new order of things out of nothing, out of small elements that can be found. And that‘s the passage from the architecture to the book, I would say, that‘s exactly what happened historically: the origin was based on the book [T: …which is carried around and read by everyone.] Exactly. [T: Instead of being bound to a place…] Yes, it’s portable.

II

aesthetic thinking vs philosophical thinking • the role of an artist •

the problem of representation • the ‘sublime’ • abolition of distance

T: So can we perhaps jump to… [N: …’Now’? [laughs]] Yes, to the ‘now.’

G: So you didn‘t really answer the question how these ideas are modern in a way that they correspond to the now and did they change from the point where they originated and how.

N: I think the most important thing is to understand that I‘m not a philosopher. I am an art critic and curator and I think as a curator. So all the ideas I could express are translations of what I see in the studios and exhibitions, that‘s really important. I don‘t invent the concept in order to apply it to art or artist—it‘s exactly the opposite. It‘s a way of thinking which is really different from a philosophical one.

T: So it‘s an aesthetic thinking.

N: Yes. I think so, it‘s my basis. The same way Lacan could invent concepts out of this very specific field which was psychoanalysis, in a way I‘m trying to do the same from art, aesthetics and I think it is legitimate to do so. I think art is a fantastic point of view from which we can understand the ‘now’ and where we can dwell in. We can really expand artistic intuitions and ways of thinking into much broader contexts and then use these ideas that are up to a reader to understand. But in a way it is always about a connection between art and society.

G: So you trust art and artists to provide you with the experiences of contemporary life. It also means you trust the sincerity with which they come up with ideas. But they are also influenced by these ideas, so there is a two-way process. They‘re not just experiencing life as it is. Sometimes artists want to fit in the contemporaneity.

T: So the question perhaps is whether an artist is seen as a litmus paper of some sort, an artist as a ‘detector,’ because she detects something—a vibe? Something is happening in her world, and perhaps an artist is not necessarily conscious of what she is actually doing?

N: Sometimes, yes. But it would be a bit reductive to see all artists as a kind of a warner or whatever of this kind, but if you read what is going on in their studios and exhibitions, you can develop a very specific vision of our times. Sometimes an artist is not fully aware of what he or she is doing, yes, but sometimes he or she is fully aware, [G: …to a certain extent…] so you have many many approaches to the world that can‘t be reduced to one.

G: But then there is a question of isolation of the art world; and, most importantly, art world is also part of the global market: quite often artists are not in full control of what they are doing, it is not fully up to them to disrupt the market relations. And when it is up to them, they choose in favor of the market.

T: I come from art background as well, as I started my education in art academy, but I went for theory immediately after graduation. I often try to reflect on my own ‘escape’—because in a way for me it was an escape from ‘Egypt’ into something: into the ‘desert of the real,’ into desert of ideas in order to rethink everything. I remember those conversations with some of the artists about the issues of representation: it was a motive of an artist who represents something—consciously, unconsciously, perhaps it doesn‘t even matter, because what does matter is the result. This issue revolves around how and where artistic ideas are distributed, under which conditions, who is visible, who is not visible. So it is one of the key questions: representation and the visibility of this representation, how and where it circulates, in which circles. So these are the conditions of my interest. Such focus on the conditions themselves can reveal something about an artist, or about who is in the process of selection or the decision to participate or not to participate. We had a really interesting initiative in Lithuania recently—there is a huge book in two volumes: (In)dependent Histories of Contemporary Art which focused on what can be called the ‘unrepresented.’ What or who is ‘unrepresented’ in art? How does this ‘unrepresented’ remain operative in the official discourse, or historical discourse? It was an attempt to create an alternative history or, rather, to recognise the alternative history and I figured it was one of those rare attempts, at least in Lithuanian recent art history.

I found it interesting that there was this need to discuss the question of representation. Another example is when artists participate in an event, they establish a connection or a link between the content that they produce (art itself) and the context that they “use.” This creates a certain structure: form and context. It is a really simple structure, but the fact is that one can never escape it. So the question is, how we think about this structure. Does it reveal something?

N: To answer your question, one has to analyse the different modes of what used to be called ‘representation.’ I would say, representation is just one aspect of artistic practice. Sometimes it can also happen that an artist presents something: it‘s presentation, it‘s taking something out of any context, out of a functioning world and presenting it. An artist sometimes designates something, it is not representation anymore, when artist designates the situation, indicates a way toward something else—that is another facet of art. Sometimes an artist uses already existing structures and that‘s the way he or she is involved in his or her practice: by using the world, using already existing structures, using institutions, using the apparatus of everyday life. That‘s another postulate. So you have four attitudes that are equal to representation in contemporary art today. Neither of them is stronger than the other. They all co-exist.

T: So, what is representation to you?

N: Representation is one figure of this work of… work of… we should probably try to find another word for this, because ‘presentation,’ ‘designation,’ ‘use’—they no longer… OK, representation is presentation of a different aspect of the work of showing. To show something is completely multi-faceted today. Every exhibition mostly uses these four possible attitudes. And then we can talk about representation that is also something else—i.e., when something cannot be presented. It‘s a Kantian definition of the sublime in a way, it‘s what Lyotard was talking about when he was referring to the ‘sublime.’ So, presenting the unpresentable. And it‘s like in a way, in Lacanian psychoanalysis, the notion of the objet petit a: something which is always missing—that‘s the real in Lacanian philosophy. The Real is something that escapes, that cannot be presented, that can only be seen through anamorphosis and that is also a figure which is very strong in contemporary art. But they are not excluding each other, no, all those figures are actually adding to one another. I think.

T: I just remembered one of your passages on Alain Badiou. Did I sense a certain critique towards Badiou?

N: Yes, I‘m not always agreeing with Badiou.

T: When Badiou speaks about representation, for him there is a situation and it‘s representation, which is what he calls a ‘state.’ So there‘s an event and there is always something like a memory of this event in a representation.

N: But what we call representation here during our discussion is nothing but distance between what is lived through our everyday life as something ‘real’ and it’s [representation]. It’s the distance that [one covers in order] to see something in an exhibition. Representation is only about distance and what we call “showing” subsumes all those four different attitudes. It is a distancing away from reality, it’s a critical distance. That’s the way we could define what we see in exhibitions: sometimes these are the same objects we see in our everyday life but now they are seen from a critical distance. It’s very simple in a way, but I don’t think there is any other more precise definition that would embrace everything that we see in contemporary art exhibitions.

T: So “distance” is one of those keywords that you use and perhaps for you an art exhibition is one of the ways to see distance at work?

N: And that’s also seen in the exhibition here, but it is seen from a totally different point of view which is the idea of phantasmagoria which for me (and that’s the key for this exhibition) is also a kind of ancestor for the contemporary art installations. From the very end of the 18th century this very specific—almost ephemeral—type of events that originated in Paris at the very end of the 18th century, is very important for me. And the key word is ‘distance’ because this is what was actually happening during the last two centuries: it is the abolition of distances.

T: Let’s talk about this abolition or disappearance of distance. So the distance itself vanishes, but there is a condition of this vanishing, which is primarily a technological, so perhaps it means that distance withdraws into the unconscious. Perhaps this is also a ‘Heideggerian’ moment: it was Heidegger who made us aware about the withdrawal of a tool or an object. For example, you are not aware about the chair until I mention the chair—this is what withdrawal is for Heidegger. Abolition of distance perhaps happens in the same fashion, because we cannot escape the conditions of this disappearance. Today we travel easily: we simply board the plane and the world becomes accessible because of that. This is not anything new, the very idea of technological conditioning does not give us anything new philosophically, but what actually is interesting is how art contributes to this: how the very structure of art contributes to those conditions of abolishing the distance? There is something in art, that always seems to resist the technological conditioning: it can question it, it can refuse it, it can distance itself from it, but at the same time we have a paradox—art cannot do without technology.

G: And this is how it also provides distance.

T: So, the abolition of distance.

N: It’s a crucial question I think. Let’s think about the definition of the aura by Walter Benjamin, a unique apparition of something which far away— that’s exactly what has been abolished in contemporary art in the last 30 years, I would say. It’s not a unique apparition of something which is located far away—sometimes it can be something very close to us and reproduced one million times. We are living in a totally different visual and intellectual context compared to the time of Benjamin. The role of reproduction has totally changed, and that is the new paradigm that an artist has to address today.

The exhibition “Intense Proximity” that Okwui Enwezor did in Paris was also about this collapse of distance. Based on the analysis of anthropology and ethnology. Going far away to bring back images and documents about the way people were actually living. Today, what is really striking, is that technology is in your pocket: we have smartphones to take pictures…

G: …yes, if you are lucky to have them…

N: …we have computers to record images. Images are absolutely everywhere: Facebook and all the social networks are providing us with tons and tons of images from everywhere in the world every day. It is exactly this collapse of distance that has become a reality. It is something that all of us live with on a daily basis. And that creates the context which is radically different from the 20th century. We have to address that and take that into account if you want to understand the evolution of the aura.

You were mentioning the role of art in this erasure of distance. Language was originally a way to destroy distance: when you write a text you can talk about, say, a ziggurat of Babylon while being in Kaunas. It is an abolition of distance. And artists are addressing realities which are very far from them. But what is actually interesting is that modernism in the 20th century was actually based on the reflection about distance. We have artworks that László Moholy-Nagy made by telephone in the 1930s—as far as I know, these were the first ones of this kind. In the 1960s it allowed Lawrence Weiner to work in the same way: he can be in New York and do a show in Amsterdam because it is all about language. And you can reproduce the language. Even Sol LeWitt was working in the same way.

Today I am showing a piece by Liam Gillick, who is very close to Weiner and—that’s not accidental—he is showing a piece created by correspondence that could also be collaborated by others. We are in a very interesting dialectics between here and there all the time. And that’s also one of the main issues of the exhibition.

III

critique of postmodernity • critique of presence • demand of presence in art • act of resistance • critique of the ‘originary’ • Derrida and language • targets of altermodernist critique • postmodernism as ideology • economical crises and postmodernism

T: One of the points [in your book] is the critique of postmodernity. This is one of those interesting hot points. I must recall here the whole postmodernist project of critique of presence. It is all over in the works of any post-Heideggerian up to Derrida. The absence of distance or the vector that draws you to this state of ‘distancelessness’ is precisely what they were criticising.

N: But art was—and still is—linked to the notion of presence: you have to go to an exhibition. Seeing an artwork on the screen is not enough, you have to see it. Exhibition is one of the last places where you have to move towards the place in order to see something. Cinema is slowly vanishing, the theatre is still there, of course, but the very last place where presence has something to do with our understanding of the language which is presented is contemporary art. Exhibitions are also small temporary temples—places to go. That is the way Georges Bataille was defining the museum as a kind of lung—the city goes into this lung in order to have some air, in order to breathe, to refresh itself.

But of course within this structure of presence artists are criticising this notion of presence. And it is a very interesting historical moment. The structure of distribution of artworks demands our presence, while artists are criticising this presence.

T: What do you mean by “demands our presence”?

N: One has to see the artwork. You receive an invitation for an exhibition—that’s the demand. You are not supposed to stay at home and look at the website. Not yet! It will happen.

G: Presence has to do with our body.

N: Yes. And also it is an act of resistance—one has to take this into consideration. Everything is made today in order to erase our body or our nervous system. According to the logic of entertainment, you are not supposed to bring your body in many places today, bodily presence is something that has become rare. Working with one’s hand can also be an act of resistance in certain situations. Resistance towards total mechanisation of the production.

T: So this is reflected in the new trend of the ‘maker movement’ which calls for just ‘making things’ manually. So the last bit about the critique of the postmodernism. In your book you mention the critique of the ‘originary.’

N: Yeah. It is a common point in all my texts.

T: Do you see the dependence on the ‘originary’ as one of the defining traits of the period that responded to modernity—i.e., postmodernism?

N: Yeah, I think so. At least one important part of postmodernism was based on identities, on the vindication of identities, and it always has something to do with origins, and that’s what I am criticising. Many postmodern modes of thinking have been based on a kind of assignation of residence for the people—e.g., if you belong to such and such minority, it’s enough to define your identity—I don’t agree with that. Identities are constructions and it is much closer to the queer way of thinking than to most of the postcolonial thinking, for example.

T: What do you think about Judith Butler’s notion of [sexual] identity [as a performative construct] then?

N: Yeah, I think it is close to this way of thinking actually. Much more than many postcolonial systems which are based on the fetishization of the origin, and that is what I think is obsolete now and we have to go through it in order to find new ways of thinking.

T: But isn’t it interesting that both Derrida’s and Butler’s and many other’s critiques of the idea of the originary—also you can find it in Derrida a lot—comes from what we call ‘postmodernism’?

N: Not really, I think Derrida is coming from structuralism -never forget that, it’s really important.

T: That is true. But that was not what I meant.

N: He was incorporated, included in what’s called postmodernity, but in many ways he’s beyond that.

T: So is it that Derrida makes a detour over what we call ‘postmodern’?

N: Derrida is postmodern in one specific way which is super important in his work: it is the fact that he has actually created a kind of closed territory which is language. From the very beginning of his work there was nothing outside the text, you cannot get out of the text, and that is very postmodern in a way. This way it is postmodern, but many of his concepts and ideas are actually coming from the Ecole normale superieure where he studied together with Michel Foucault and Louis Althusser who were already at that time teaching there. You can see the structure in his first text Of Grammatology.

T: So basically his critique of the originary is, shall we say, ‘correct’—although I don’t like this word, but let’s use this word for now—it is ‘correct’ but the tools he is using or the conceptual grounding is restrictive because it is language.

N: For me he was always almost jailed in this pan-linguistic vision of the world which is very structuralist actually, and not postmodern at all. It’s something you can find in the legacy of the first wave of structuralism—Roman Jakobson, etc.

T: So who would be the postmodern targets of our ‘altermodern’ times today?

N: Good question, but difficult to answer.

T: Perhaps broadly.

N: I think strangely enough I should give it more time because it is a very wide question. But [in general the target is a] specific type of discourse which is shared by many rather than one two or three thinkers. It’s more like a form of ideology, I would say. Strangely enough, postmodernism is much more an ideology than someone’s articulated thought. It’s spread out, it’s not going from one or two specific sources, it’s the combination of many sources that create a discourse which has become an ideology.

T: So it’s also difficult to define the point in time when postmodernism crystallised itself.

N: But the term just appeared in the mid-70s and it is interesting to see that it was exactly at the moment of the oil crises in the Western countries, which happened exactly in 1973. And then very shortly after that Western countries understood that oil was not infinite, you could not spoil tons and tons of energy, it’s not possible any more. Progress, as it was understood in the modernist times, was over. And then ecology appeared both in Europe and in America at this exact moment. The political ecology appeared as a shared consciousness. That’s a very important moment.

T: So this shared consciousness is one of those targets of an altermodern critique. This is the kind of state that you want to turn yourself against in a way.

N: Absolutely. But the main effect of the oil crises was the financialisation of the economy. Suddenly it was not based on the exploitation of the specific soil but on the transformation of the financial system into something totally abstract. That is what America did, while Japan went into technology, and Europe basically went into the financial system too. 1973 was the year when states had to borrow money from banks instead of producing money by themselves. That is a historic date because the crisis of 2008 is born exactly in 1973. That is why I tend to—and I know it’s a bit artificial—but I tend to say that postmodernism lasted from 1973 till 2008 because it was based on a very specific idea of the financial system which collapsed completely in 2008. Well, maybe it did not collapse, but at least there was a huge crisis which transformed the world completely—just see what is happening in Greece at the moment. So the idea that soil was not important, the ground was not important any more, the Real was not important any more—all that appeared in 1973. One might even say that since then—the end of postmodernism [in 2008]—we are slowly getting back to the Real, but in many ways, not in a caricatural way. We want to find something more solid…

T: So perhaps this is how we can actually connect it to the speculative turn, and the turn toward the real in philosophy.

N: Yes, absolutely. It’s a side effect of it.

IV

the problem of roots • plasticity • phantom pain of an amputated root •

treating the loss of uprootedness • the dualism of globalisation and fundamentalism •

the need to escape from the dualism • false idea of contemporary art

T: Perhaps now we can jump to another topic. Let’s talk about your idea of a radicant. In your book you launch a critique of rootedness and you insist on the disappearance of roots or at least the loss of importance of roots. You describe it in a very visual manner, so it’s easy to start thinking about this notion in terms of, for example, Deleuze and rhizomatic networks. The notion of rhizome has been exploited a lot, but the way you introduce your concept is quite paradoxical. Say, if I am a radicant, instead of putting down roots deep into the soil, I am growing my roots on the surface. That way I can move around and adapt to any other area. I am no longer tied to a specific place.

N: One can also consider different uprootings (plural) [or offshoots]. It’s important to think that these things are not exclusive one to another: the idea of radicant is the horizontalisation of one’s way of thinking, one’s own life in a way, it’s not the verticality of the place one was born at, or the place one decided to live. Uprooting is very vertical, while radicant offers a very horizontal plain.

T: So the root does not disappear after all—it changes instead.

N: There are multiple roots. If you take the ivy, for example, to go back to an image, it does have roots, but it depends on the soil. On some surfaces ivy would grow only a really superficial root, while in a more fertile ground it can grow a much deeper root. It’s not roots against uprooting, it’s more complex than that. I think this complexity reflects the complexity of the subject in a way.

T: It made me think immediately about what Catherine Malabou is working on.

N: Plasticity.

T: Plasticity, exactly.

N: Not super familiar with it but…

T: This idea resonates with the notion of a radicant a lot, although I am not entirely sure because I did not familiarise myself with the notion of a radicant well enough. The thing is that Malabou borrows the term ‘plasticity’ from neuroscience, and in French plastique also means ‘plastic explosive.’ But the main idea is that we are all plastic in the sense that—to go back to the language we used just a minute ago—we have roots and we do uproot ourselves, but only for a certain period of time until something happens, until we have to relocate because of some catastrophe.

N: Exactly, then the ivy does not die, it survives and evolves, because if you cut the original root of an ivy, it still goes on. I think to have multiple roots is the only way to survive the disappearance of your origins.

T: But the key difference between those ideas is that in plasticity there is still this linearity. Malabou claims that you can not be plastic in the sense that I am multiple in many places at the same time. It’s not what being plastic means.

N: Then the difference for me is that the idea of a radicant represents a ramified line. In radicant you have ramifications, but it is still a line as well, so they are not opposed. It’s important to get out of the binary oppositions here. I think one of the characteristics of postmodern thinking is binarism of yes/no. A line is not necessarily opposed to a tree. The very pattern of the radicant combines the two actually. And that is what interests me a lot. In a way one can see a tree as a line: the direction is always the same but it does ramify and the two are not opposite.

T: There is this interesting passage from your text about the radicant, I quote: “It is roots that make individual suffer. In our globalised world they persist like phantom limbs after amputation causing pain impossible to treat since they affect something that no longer exists.”((Bourriaud, N. (2010) The Radicant. New York: Lukas & Steinberg, p. 21))

N: That’s the unhappy exile, the unhappy emigration, and that is a very contemporary phenomenon.

T: So do you think there is a way to think about some new mode that would cure or treat this phantom pain, this loss, this lack?

N:The Radicant was written in this way.

T: Do you see it as a some sort of a treatment therapy or psychoanalysis, if you will?

N: Oh, I wouldn’t go that far… Well, psychoanalysis—maybe, yeah. Maybe it’s something I am quite familiar with, so in a way yes, this discourse might be somehow linked to psychoanalysis—a kind of psychoanalysis of the collective disease which is based on the fetishisation of rules. There is a two-fold enemy I am fighting against in The Radicant: one is the normalisation and standardisation of the world according to what’s called globalisation; and the other one is the fetishisation of the roots in nationalism, various religious fundamentalisms, etc. These two ways are my enemies, so you have to find the third way because what we actually see around us now is the mix of globalisation and fundamentalism.

T: I agree. Perhaps this is what makes this idea so vibrant: you talk about globalism but at the same time you still use the notion of root. But the discussion or thinking doesn’t stop here, we still have a lot of questions. For example it might seem that the radical (sic!) leftist politics can turn towards some sort of a weird nationalism when it appeals to a certain uprootedness—this is what we saw in Greece recently. It never happened before, at least to that extent. Perhaps I sense a similar kind of thinking here in Lithuania as well because on the one hand leftist thought goes absolutely against any kind of nationalism or any kind of fundamental fixation, it’s been criticised throughout for a couple of decades now, but on the other hand we stick to it when we oppose globalisation. What can be criticised is the false solution that we have overcome the problems of nationalism through being truly ‘global.’ I guess those problems have become more complex. I am always suspicious about any kind of ‘solution’—it is never a solution, it’s always a process.

N: But The Radicant calls for individual solutions or collective ones but in smaller groups. It is not about trying to avoid specifically this disaster of the uniformisation of the world which is not the answer to the radical fundamentalisms or nationalisms. We shouldn’t jail ourselves or lock ourselves up into this dilemma between globalisation and fundamentalism. It’s urgent to find other ways, otherwise we are all condemned. So art is important here because I think the solution will come only from creativity. Assuming the fact that every existence is a construction and a creation, it means it is also related to art, and that is why I am [mediating] for art or even for a political scene. It is really important to address it and propose solutions, and artists do, actually.

T: For example, one of the problems artists are addressing here in Lithuania is whether to participate in the already constructed and easy to access international model of exposure—this is something I have been working on recently as well, I am still trying to get more information in order to research this problem. However it is quite obvious that there is a dilemma—and perhaps it’s not a well represented dilemma, it’s not very official dilemma, but it’s always there. Once, while I was still studying at the Academy of Arts, I was even told by one of my lecturers that an artist today has to choose between doing marketable contemporary art and thus becoming a ‘contemporary artist,’ and just doing ‘her own thing.’

N: That’s crazy. That’s based on a totally false idea of what contemporary art is.

T: What is contemporary art?

N: It is art that is made today. I don’t have another definition for it. It’s not a genre of work. What is genre, actually? In my exhibitions you have as much paintings or video art or performance art. I don’t see the difference.

G: The problem lies elsewhere.

T: Yeah, I was addressing a different problem.

N: Art is not a medium.

T: It’s not a medium, it’s not a genre. Of course, if one does her art today, everything one does as an artist is contemporary. The question is how does one see it.

N: But if one incorporates ideology within one’s work it means one is a bad artist.

G: But can ideology be avoided?

N: The main criteria to judge an artwork for me is this singularity of the proposition which is made. If I already saw it one hundred times it’s not interesting to me at all. Singularity is the key. If I discover someone with an attitude, inventing forms that I never saw before—that’s what is called ‘quality’ as far as I know, I don’t have any other criteria. Sometimes it’s not a matter of corresponding to such and such criteria. Singularity is the key word.

V

singularity • how to grow a tomato

T: What is singularity? Can you elaborate a little bit on it?

N: Singularity is the impression you get from an artist whose work could not exist if she wasn’t doing it, that’s very simple. It’s the same when you meet people—it’s not about seduction at all. Singularity is difficult to explain, singularity is exactly like we have it in the dictionary—the fact that something has not been seen or heard before.

T: Did you borrow this term from somewhere?

N: No, it’s really about being singular. A collective kind of singular. It’s not a matter of individualism, but you can be in a group of artists and be totally singular.

T: I find it very interesting the way we use ‘singular.’ I remember immediately that, for example, Alain Badiou finds it very complicated and problematic to talk about the One, the singular.

N: Yes, I know, it’s always two.

T: It’s like counting to one is the most difficult thing, and perhaps it is also an impossible thing to do.

N: But perhaps it’s not contradictory because any singularity has to find its counterpart in the audience in a way. Singularity is more of a situation, it’s always about a confrontation of someone in front of something. Or it is a situation that is created by an artist.

T: So it’s a conjunction.

N: It is a conjunction, of course, because no work exists if it’s not seen or apprehended by someone. That is a definition of art in a way. I could define singularity a bit more precisely if you want. There is a number in mathematics which is omega, the cipher omega is the sum of all the numbers plus one [ω+1, or ‘infinity plus one’]. Art—and what is singularity in art—is this ‘plus one,’ this impression that you see something that you haven’t seen before, that’s the way I would define singularity, it’s this omega number.

G: I’ve written down an example if we may go back to the problem of uprooting as a sort of linking yourself geographically as well as your own identity. You compare radicant to a plant…

N: It’s a botanical term which is in the dictionary, I didn’t invent it.

G: So we know that the plant doesn’t grow from roots, it doesn’t start there.

N: It does.

G: But it comes from the seed and then, as an upper part of the plant grows above the surface, the root grows as well in order to provide the plant with nutrition which is necessary for the plant to stay alive. So I just have this visual example of a farming practice that is based on depriving the plant of water. For example, if you regularly water a tomato, its root will spread on the surface in order to absorb as much water as it can quickly, because the surface of the soil dries out .

N: For me that’s globalisation exactly, that is the best image of globalisation: the roots are not into any soil but they are just fed with chemicals, abstract chemicals, recreating the qualities of a soil. So on the one hand you have this postmodern tomato, and on the other hand another enemy for me is the big tree with one root because that is what we call radical, it’s radicalism.

T: Yes, the radics.

N: That’s one root.

G: If I may continue with that example about tomatoes… What is interesting in the tomato case is that it is possible to grow them differently. Instead of watering it regularly you water it only once and cover the soil with hay as soon as the tomato has been planted. This way its roots grow deep into the soil because when there is no artificial watering it needs to find its natural source of hydration.

N: Sure.

G: The procedure of watering is artificial. It’s not natural because the whole system of watering needs to be taken care of constantly. But the point is how to have a system that is self-sufficient and efficient enough, because a large amount of energy is wasted for care and maintenance of the artificial watering system.

N: Absolutely.

G: Which is not necessary or efficient at all in the case of a tomato. I was told by a self-taught gardener that when she shared this non-watering idea with other gardeners, they were reluctant to apply it—they prefered watering to not watering. Surprisingly, they found watering ‘convenient.’ Perhaps, it is because watering gives people some sense of occupation and relief…

T: …and a sense of contribution.

G: And it is a relief from thinking in a way. So it is painful and hard to do thinking that would change the system. So the question perhaps would be if the idea of radicant helps us to think about systematic change or is it about describing the new state of the world—i.e., the state that changes rapidly by itself due to the technological advancement? Does this idea provide us with tools for implementing the change?

N: I think the key pattern for the times to come is the combination of the two: technology plus the acknowledgement of specific situations. Differences cannot be erased by some new kind of water system for tomatoes, so to speak. The danger lies there too.

VI

technologies as tools • the use of tools • phantasmagoria • the Post Office building •

curatorial practice • choosing artists • curator as a conductor • commissioned art

T: I found a really interesting passage from Gary Zhexi Zhang’s article on post-internet art about this technology problem. The article is called “Post-Internet Art: You’ll Know It When You’ll See It.” It’s about the aesthetics of post-internet art, and there is an interesting passage: “Art might like to talk about what it feels like to live through social media but, by and large, artists find themselves complicit like everyone else, they are always twelve steps behind the tech companies, the parameters of their freedom are established elsewhere.” So he is very conscious about this problem that we always have to be technological, but how to be technological without being behind the solutions that have been already created for us? This is the problem that we perhaps cannot escape, or can we?

N: We can, because technologies are tools. The main issue is the way we use the tools, what’s the ideology behind the tools. Any tool from a hammer to our most advanced technological device today is exactly the same. They are tools. How do you use them and for what purpose? The key problem is in the ideology, then in the ideas. People don’t want to see it because they tend to follow the dominant ideology which provides the use for those tools. But actually we can reverse that. The most accurate political task for the contemporary art is to become a kind of editing table for unproduced new scenarios from the same images. Dominant ideology provides specific scenarios including scenarios for telephones, for tools, for art, for human relationships. Art has to reinvent these scenarios, rewrite the common scenario, and provide a different use for all the tools we have, and that is a very political task, and that is the main political task—even more political than criticising the given. It’s about producing a kind of new philosophy of the use of the world in general, and the tools, in particular.

T: So what is the most important thing in using something?

N: The use is everything for me. It’s the alpha and omega in a way. What else do we have in our lives other than using? We use a table, we use this coffee cup, you are using this computer, we are using words to discuss and exchange ideas. We are using the tools that we have, and that is the core of contemporary art for me.

G: Maybe let’s shift now to this particular exhibition. In 2012 in Klaipėda there was an exhibition called “The Prestige: Phantasmagoria Now” where the motive of phantasmagoria emerged as well. We have the same concept used in the Kaunas Biennial exhibition, so I was wondering whether there is a relation between today’s art and phantasmagoria. Especially given that phantasmagoria does not just carry features of both movie and installations, but it also is or could be associated with a form of entertainment.

N: For me not at all. I wrote a text for this exhibition, but the funny thing is that I totally forgot to mention this in it. Sometimes phantasmagoria for me it’s not about entertainment at all, it’s not at this level I am using this term.

T: Is it this scary aspect that…?

N: No, it’s just the fact that it was invented by Richardson—this very strange Belgian guy who came to Paris at the very end of the 18th century. He was actually inhabiting old buildings in Paris in order to create a kind of environment. So, structurally speaking, he was the ancestor of what we call installation or environments. And the other characteristics was that it was all very much based on the idea of calling the spirits and abolishing the distance between the living and the dead.

T: That was a very popular motive at the time.

N: And it is this notion I am using here. In a way it is a comment on Aby Warburg’s quote “telephone and telegraph destroy the cosmos.” It is an interesting quote. In a way it was a starting point for this show. What does it mean? Can we now have a different point of view on this? Maybe telegraph and telephone, to use his words, are not “destroying” the cosmos but creating something different which is not purely destructive or negative but something that would lead to another perception of the cosmos. But it is interesting to see how this is happening here in the “Threads” exhibition at the Kaunas Post Office.

T: Very much so.

N: It’s absolutely perfect for me because it’s both—as we said before—communication and the destruction of communication: this old Post Office was a place both for communication and for jamming the Western radio signals like those of The Voice of America.

T: Is this fact going to be included in some way?

N: It’s included in a way that I want to keep the building exactly as it is. It’s not going to be transformed into a white cube.

G: It would not even be possible because it’s a heritage building.

N: We are going to have some white walls when needed. I could have transformed it into a white cube, but I want to keep it as a ready-made in a way. It’s not a postmodern exhibition. A ‘post office exhibition’—that’s something very different.

G: Now a practical question regarding the communication and the disruption of communication. It often happens that the invited curators do their research into the local art scene through assistance or even just by addressing contemporary art institutions—and Kaunas Biennial is itself an institution in a way—like National Gallery of Art, or Contemporary Art Centre, or their curators because of the lack of time or…

T: …because it is more convenient.

G: In a press conference of a Biennial this January you said that you don’t care about the big names but it’s usually the big or bigger names that appear on the lists of the recommended artists that gained the trust of the institutions in a way. On the one hand, we can also say that it is precisely the ‘correct’ kind of artists that are included to the list—i.e., those who were fit to represent the ideology of these institutions. On the other hand, these artists made it to the list because they are worth of the attention, because they are relevant (again, according to those who have been trusted to give an advice). So in the case of “Threads” and Kaunas Biennial, how this seemingly technical issue of research, communication and selection of participants was solved?

N: As a curator I am doing the research myself actually, so my assistant Mariana, she is mainly working on production, relations with the artists, etc. So that is the way I work. Some people can work differently but my job, my thing is to…

G: …to engage with artists directly and speak about their work, their practice?

N: Sure, otherwise what is the curator? The one who organises all those elements in order to create a specific meaning in a specific place. Just like a movie director.

T: A director?

N: Yeah, it’s not that far from it, there are many similarities.

T: I remember in one of your interviews you said something about the curator as someone who orchestrates, who is creating an opera while the musicians are still on stage or something like that.

N: I think I was addressing the idea that—just like in the opera—one can either follow a libretto, a storyline, a narrative or not, actually. A good exhibition could be visited both ways.

G: So who is the composer in this case? If a curator is a conductor and the artists are musicians…

N: The equivalent of the composer is the edition of all the voices of the artists.

T: So it’s some sort of a loop.

N: There is no composer, the music comes from the artists, I am only here to provide the storyline or the elements that stick all those voices together in a specific situation. And the nightmare of these kind of shows is to decide what work you will see next during the show.

T: You mean the challenge of how to arrange a narrative?

N: Narrative might not be the exact term for it actually, because it is not about a story, it’s, let’s say…

T: A sequence?

N: It can be a theoretical story or just a theme or an idea that actually makes the meaning move slightly towards one aspect.

G: … to continue this example of an opera—isn’t there a risk of art and exhibitions becoming for art’s sake?

N: For art’s sake? For which other sake do you want to make an exhibition?

G: To help us survive in a way. For the sake of having an experience of life…

N: But the same [is with] artists, [they] have to survive if it’s a good art.

T: If it’s a good art?

G: But who decides then?

N: Me, who else.

G: Yes, but I have a feeling that people less and less have time to actually do their work, so I was wondering how do you manage to distribute your time, how is your attention distributed?

N: I try to focus on the ensemble, the unity of the whole, and then, at the end of the day, on the details. In between there is something which is very important: it is production, contacts with the artists, shipping, etc.—something which I am not focused on at all. My main focus is on togetherness and the [construction of] meaning obviously, and then the small details like the labels, or shapes of the labels, do we need to [buy?] this colour or that colour, these kind of things—details which are really important and you can only decide if you have a clear view of the ensemble.

G: Are any artworks going to be produced specifically for this exhibition?

N: Many, I think. But I am not fetishistic about the production of new work in exhibitions in general. Sometimes an artwork can be seen in a different context and if it’s a good artwork it will also deliver new meanings, new layer of meaning. So it’s not so important to have new things like something completely unseen or works that haven’t been shown somewhere else, in Tokyo or whatever.

T: So it’s the whole combination that is new.

N: Totally, but some works are actually made here or will be produced for the exhibition so it’s both, it’s going to be a combination.

G: I am quite sceptical about the artists who get their work commissioned constantly or regularly, as there is a risk that the work will be produced to fit in the content.

N: But it’s a discussion with the curator every time. Sometimes you have to appreciate it by yourself, see if it’s more convenient to have this piece which corresponds perfectly for the purpose, or if you trust the artist to produce something totally new, if she or he has a project. It’s a permanent negotiation with every one of them. I don’t have any formula for everyone, I have a different discussion with each of them. That’s important, I think.

G: But should art be commissioned at all?

N: Yeah.

G: So you have no problem with commissioned art?

N: No, why would I?

G: Because I think the artist should show commitment to the…

N: But that is what a commitment is if you do a specific project for the exhibition.

G: A long term commitment.

N: What is the long term here? It’s a temporary exhibition, there is no long term. Commitment to what you mean?

G: Commitment to the problem that they are working on.

N: Ah, I see what you mean. But you know for example if you are doing an exhibition about any theme, this theme can belong to the work of an artist who can be really deeply involved with it from the beginning of her whole career. That is the way I invite artists generally. Ah, by commission you mean something which has nothing to do with… Ok, I got your point. No, it never happened to me that I would invite an artist and ask him or her to do something specific that has nothing to do with her or his work. No, never. It would be stupid, and nobody would do that, that’s totally crazy.

G: But you might not need to ask them to … Because that might be the solution for them how to get into the show.

N: No.

G: But you cannot guarantee the sincerity.

N: But if you choose the artist… I don’t know, it’s my job, I would never choose an artist for an exhibition who doesn’t correspond to the idea of an exhibition, so the problem doesn’t exist for me, it has never happened.

G: So the way you work is you come up with an idea and then invite artists who would then correspond to this idea.

N: Of course.

G: And you modify, you sort of embrace the differences, and sort of make an amalgam from it, but it’s not something that you have envisioned in your research…

N: My life is a research. I don’t do research specifically for one thing, I do it every day of the year.

G: So if artists produce the material according to your own ideas and the concepts that you create, then are they not just illustrators of those ideas?

N: Never. Also why it’s very bad, so it would be stupid to ask an artist to do something bad. If it’s artificial, if the connection is artificial we will always see it—it’s obvious, it’s clear. It creates a bad zone in the exhibition.

T: So perhaps the question is about the solution: whether it’s descriptive or prescriptive?

G: A diagnosis.

T: A diagnosis. Yes, it’s the problem when we create a concept or a notion and then we look for an event that would match this notion—this is something Badiou is interested in, he names and then he waits for an Event to correspond with its prescriptive naming. Or is it a descriptive mode that we are talking about? There is a difference between them.

N: It’s not a dogmatic approach that I have. When I start working on an exhibition, first of all I do the lists of artists whose work goes into that direction, obviously—that is the first level. And this is how I developed this show, for example. What is the most phantasmagoric side of the work—what are the aspects of the distance and correspondence, etc. You have to decide things and you have to incorporate those themes into the general view, but it’s never about asking an artist to correspond to an idea, that would be a wrong interpretation of a work, so it’s pointless.

T: So now that we have discussed the idea of the show, it is going to be interesting to experience the ‘before’ and ‘after’ thing.

N: Yes, I am impatient too.

Special thanks to Eglė Matulaitytė for her help during the preparation of the material.

Kaunas Post Office before the exhibition preparation works, Spring 2015. Photos: Arnas Anskaitis