Photo: Lithuanian Mycological Society

The lifespan of the fruiting body of a fungus, except for some polyporaceae fungi, is very short – from several hours to a dozen days. People believe that fungi grow very fast, which is partially true, but this only applies to what people call a mushroom, the overground fruiting body of the fungus. All the rest of the fungus is mycelium, a branching network of long thread-like hyphae. A similar burgeoning network of microorganism research can be detected in the forest of Lithuanian contemporary art, or mobile artist laboratories replicating this forest. The evidence for this has become denser recently, provided by certain art phenomena, exhibitions and discussions that have emerged over the recent years. It seems that the somewhat delayed or hitherto out-of-place spores of reflecting on post/trans-humanism, the Anthropocene, or ecosophy have only recently enabled us to begin gradually identifying the fruiting bodies of art in an attempt to discern the antibiotics, vitamins, growth stimulants, ferments or organic acids from them, and determine which are destructive or protective. Nevertheless, manoeuvring between a lack and excess of certain themes in art also prompts one to think about certain art ecologies from the use of recyclable objects, themes or motifs, to sustainable consumption of art and culture, and their universal visibility or intelligibility. Are such art phenomena (still) unknowable like mushrooms – organisms of extraterrestrial origin, which can intoxicate or cure, spring up after the rain in some cases, and live from just a few hours up to several millennia? Even if these phenomena are knowable, does art, like mushrooms, then lend itself to being cultivated somewhere beyond its habitual forest, and does it also agree to participate in conjunctions of new processes without being asked?

Photo: Lithuanian Mycological Society

The world of mushrooms is one of the largest and least studied. Only about one-hundred to three-hundred thousand mushroom species have been described to this day, a number that is supposedly only one fifth of their total. It seems quite natural that the proactive research of species was focused on humans themselves in the first place. Discoveries in human morality, faith and behaviour gave way to the glorification of the human mind and humanity’s achievements, particularly the technical ones. The epoch of self-fetishism spawned misanthropes and the hikikomori (引きこもり, meaning literally “pulling inward, being confined” in Japanese), who experience alienation, prefer browsing the Internet to sleep, and stay year after year in the same room, in the same bed, like self-reproducing and self-destroying fungi in Petri dishes. We have become hybrid versions of our own technological networks, mutating and evolving depending on the speed of development of our prostheses. Either intuitively, or in some cases more consciously, we have constructed networks of survival that mimic nature’s symmetry and harmony. As if parenthesising in the brackets of knowledge the facts about organisms which live longer than us, to apply the same mechanisms of surviving longer on Earth to ourselves. “Earth’s natural Internet”, was how Paul Stamets, one of the most prominent American mycologists referred to mycelium in the 1999 Fall issue of the Whole Earth Review magazine (p. 74–77). His research on mycelium reorganised biology into bio-logic and made it possible to view mycelium as an example of social [self-]regulation rather than just an unexploited element of bioproduction. In his 2008 TED talk, Stamets presented six different ways mushrooms could save the world: They can restore habitats that have been devastated by pollution; they can naturally fight flu and other diseases; they can kill ants, termites, and other insects without using pesticides; they can create a sustainable fuel known as Econol; they can strengthen the immune system of humans and the environment due to the fact that there are around fifty species of medicinal mushrooms rich in protein, fiber, vitamins C and B, calcium, and minerals which also lower the risk of cancer, heart disease, and allergies; the future of our human health depends on creating sustainable farming practices, of which mushrooms can help clean up the soil that has been polluted by industries producing toxic waste.

Darius Žiūra, from the series Forbidden Fruit, 2010–…

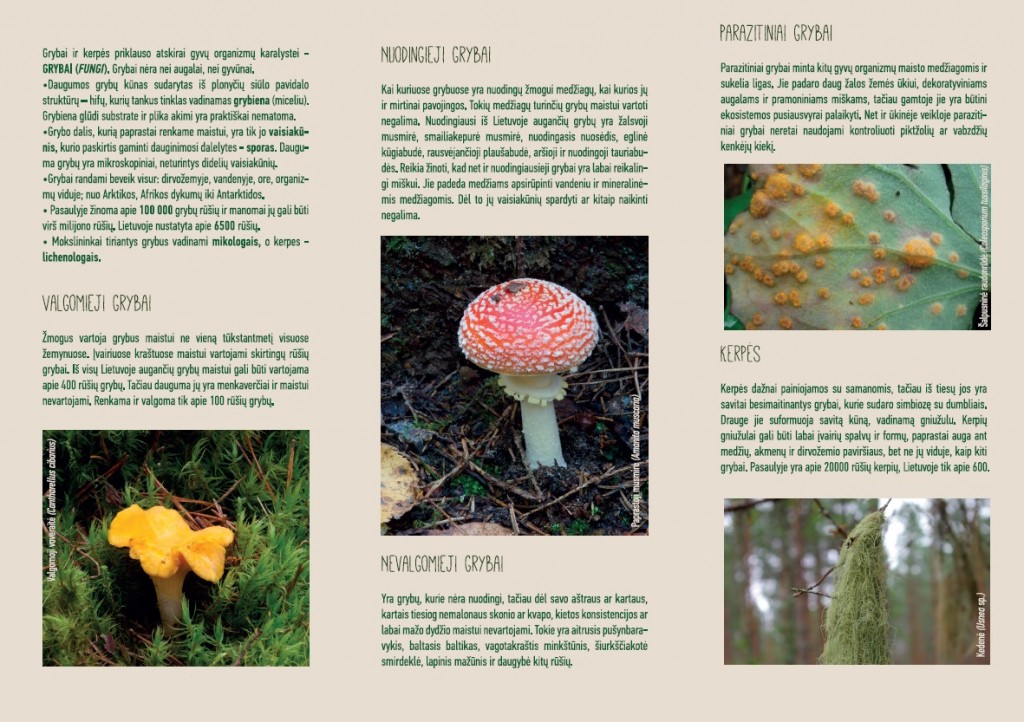

Hence, we are turning into mushrooms, and any separation from micelium, the network woven by the hyphae, could mean death or terminal illness. This somewhat straightforward concept and previously mentioned processes were illustrated by Darius Žiūra in his exhibition SWIM at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius in April–May 2014. Žiūra drew interspecies parallels by “planting” hallucinogenic mushrooms next to photographs of prostitutes in the exhibition hall. Without invoking any special bio-genetic scientific substantiation, Žiūra grasped the eroding distinctions between humans, animals, machines or fungi in a literary, seemingly intuitive way. Tackling the problems of dehumanisation and (the necessity of) humanness, Žiūra employed the symbolic allegory of mushrooms to forcefully expose his perception of humanity in decline. The exhibition presented particular human beings as toys of primal instincts, as unknowable as four fifths of all fungi species, dragged out of bed or a Petri dish just like us, the ones looking at them – the same kind of alienated misanthropes.

Darius Žiūra, SWIM, CAC, 2014. Photo: Marta Ivanova

For almost two hundred years, naturalists were trying to determine whether mushrooms were plants or animals. Finally, in the second half of the last century they established that mushrooms were an immense autonomous part of living nature: the kingdom of fungi. About one thousand fungal composites with antibacterial and antiviral properties or biologically active elements are currently known. Such facts which demonstrate our meagre knowledge seem to suggest that after we study our existence and our ever-improving daily lives, the desire to explore our environment and enigmatic microorganisms also appears natural and necessary, albeit somewhat primitive and awkward, in that it can raise particularly sensitive questions. The constant colonisation of microscopic life forms for our own benefit – by means of “instrumentalising” certain properties or bodies – relates to another aspect of Žiūra’s exhibition, and leads us to the mushrooms grown in the same CAC hall during the XII Baltic Triennial (2015) for the laboratory-style exhibition Psychotropic House: Zooetics Pavilion of Ballardian Technologies, as well as Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas’ earlier Zooetics project which acts as a platform for exploring future environmental fictions and models. Curiously, in this latter case, the literary membrane of J. G. Ballard’s sci-fi idea seemingly legitimised the use of “psychotropics”, while only a year earlier, the psychedelic Psilocybe cubensis species mushrooms from Žiūra’s exhibition had been banned by the authorities.

“There is no working strategy that stipulates collaboration between scientists, the Mycological Society, the Forestry Institute and other organisations. Hallucinogenic mushrooms are considered so dangerous that they are included in the list of Class A drugs and psychotropic substances, though it is possible for any teenager to buy the mushroom spores, mycelium and even the mushrooms themselves online, receiving them in the mail.” (Darius Žiūra, “SWIM”, Satenai.lt, April 15, 2014). Interestingly, the psilocybin contained in these mushrooms is an alkaloid similar to capsaicin in chili peppers, responsible for their hot taste), the stimulant cocaine and nicotine, one of the most poisonous alkaloids. Although there are obvious differences between the danger of the mushroom species which were exhibited and intended to be exhibited in the two mentioned exhibitions, this still points to several things. First of all, the moderately or ecologically used themes of microorganisms, ecosophy and critique of synthetics in art have become somewhat domesticated and more widely spread over the year. Equivalent ideas had been grown earlier, for instance, by Maurizio Montalti, a designer, artist and engineer-turned-researcher. Montalti established the Officina Corpuscoli in Amsterdam in 2010 as a trans-disciplinary art studio which focuses on researching ecosystems, microorganisms and their symbiosis, mostly working with mycelium and conducting futuristic design tests. One of their long-term scientific research projects The Growing Lab uses mycelium in the process of creating new materials. The project’s goals are to transform the consumption-based economic system into an ecological one based on energy saving, reduction of carbon dioxide emissions, and cuts in production costs. Mycelium is used to grow dishes which can replace plastic containers. The results of this project were exhibited in Montalti’s show The Future of Plastic at the Fondazione PLART art centre (Naples, Italy) in September 2014.

Maurizio Montalti’s exhibition The Future of Plastic. Fondazione PLART in Naples. Curated by Marco Petroni. Photo: Maurizio Montalti

Another example from the global context is the building blocks grown from mycelium by the Canadian artist Philip Ross. Interested in mycology and bioengineering, the artist manipulated the properties of living microorganisms and used them to create sculptural objects. Such micro/mycoarchitectonics seemingly shifts the role of nature that is constantly controlled up till now by human design, as it now acquires the right to self-reorganisation. One can only speculate subjectively whether the growing algorithms of such topics in art are not, in fact, just an echo of everyday life becoming increasingly greener. Recently, there has been an increase in more eco food stores and vegan restaurants opening up, more raw-food cookbooks, more people running all different kinds of marathons – to demonstrate their healthy lifestyle, and the expansion of craft-based thinking. We are going back to our natural origins, and this effect of the zeitgeist is shaped by political, ecological or ideological trends.

It is not just the topics of microorganism domestication, but also their very circumstances which have led to the emergence of new administrative responsibilities and institutions (or at least a basis for these to emerge) which seek to discuss the interdisciplinary relations between new formations and the consequences of technological advancement, from the Extropia Institute being one of the most vivid examples of optimist humanist philosophy, which fostered dreams of eternal life and ideas of nanotechnology, biomedicine and cryonics, to the negotiations between national delegations during the Paris Climate Change Conference in November 2015 that lasted nearly two weeks.

Officina Corpuscoli studio’s The Growing Lab project. Demonstration of a growing bowl

The aim of the Zooetics Pavilion was to demonstrate earthly collaboration between different life forms – in this case, mushrooms and humans. The idea of testing the sci-fi premise that objects, buildings or forms could not only be produced but also grown, presupposes the condition of mycelium’s compliance or a certain mycoeugenics in an attempt to invent the best and most sustainable compound, improving its properties primarily for the benefit of humankind. If we understand the kingdom of mushrooms to be separate and an autonomous part of living nature which populates the Earth even more densely than humans, we face the legal and moral aspect related to experimentation and its consequences rather than exhibiting. So far, in the context of these artistic collaborations, the same legal acts declare the helplessness of the human being in one case, and of mycelium in the other. Who will determine the right to grow whatever and whenever one wants in the future? Will a Myco-ethics Inspectorate join the number of existing animal rights and plant rights institutions for environmental protection at some point? Such speculations are just as fictional as the objectives set by the Zooetics Pavilion, which prompted us to reconsider the role of artists in developing such scientific topics. Are they members of the ecosystem of future processes who have an exclusive right to be autotrophs (producers), in this case producing visions of future life while performing the roles of a visionary, biochemist, naturalist, mycologist, lawyer, and finally, artist? At this point, the field of art becomes reminisicent of mushrooms again. It seems to have a kingdom of its own that resists clear categorisation because it too is flexible and functions like a wayward playground, making it possible to take different roles and create new possibilities for survival and coexistence.

Opening of the XII Baltic Triennial at the CAC, 2015. Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas, Psychotropic House: Zooetics Pavilion of Ballardian Technologies, 2015. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko.

Saprotrophic, parasitic and mycorrhizal fungi are distinguished based on nutrition. It is estimated that around fifty to one hundred-billion tons of organic material are synthesised annually in various ecosystems by saprotrophic fungi. Parasitic fungi feed on secretions of living organisms. They live in the organisms of plants, animals, even humans. Mycorrhizal fungi coexist with plants and form mycorrhiza – the symbiosis of a fungus and a plant. Still, it seems that from a nomadic perspective the differences between the ability to change and redesign our human identity and the identity of other organisms, anthropocentrically, determine the view of our own coordinates in regard to the mentioned organisms and the whole ecosystem in such art projects. In a situation of inevitable change of the environment one must acknowledge the relative nature of unchanging values and identities, which means that we might have to recognise the previously subordinate organisms as equal or even superior to us. According to the Norwegian ecosopher Arne Naess, empathy for all other organisms does not mean diminishing sensitivity to humans: “We don’t say that every living being has the same value as a human, but that it has an intrinsic value which is not quantifiable. It is not equal or unequal. It has a right to live and blossom. I may kill a mosquito if it is on the face of my baby but I will never say I have a higher right to life than a mosquito.” (Walter Schwartz, Arne Naess’ obituary. The Guardian, January 15, 2009).

Bacterial Love Letters papermaking workshop with Wojtek Mejor and Andrew Gryf Paterson. Photo: Lina Albrikienė

Here I would like to mention the Bacterial Love Letters workshop held at the Malonioji 6 project space by the artist and curator Andrew Paterson in 2015. This workshop presented a method of making paper from plants in order to “write” on it with local bacterial cultures. It was interesting to learn how microorganisms were employed here without altering their properties artificially, and how their informational superiority to human linguistic communication was revealed. What a mysterious, unfathomable yet universal way it was, both a medium and an equal conversation partner. Perhaps such conceptually, non-anthropocentric and holistic art which treat all ecological collectives and totalities as tantamount is capable of harmonising the tension-filled global world more effectively than political tools. At this point, one could also recall the fourth Interformat symposium on flux of sand and aquatic ecosystems, which took place on May 22–25 2014, at Nida Art Colony. Here, artists also reflected on the sensitive resonance of nature’s fluidity and our relationship with it or vice versa. They also addressed the need to convert our perspective into more of a post-humanist one. Coming back to the events that were part of the XII Baltic Triennial, Valentinas Klimašauskas’ readings about the restoration of biological species How to Clone a Mammoth and the series of telephone conversations titled The World In Which We Occur curated by Margarida Mendes and Jennifer Teets, have left a mammoth’s footstep and a missed call in this text. These two events, which employed an archaically verbal approach without additional technical means, except for a telephone, made me think about (increasingly marginalised) direct verbal communication, possible only between humans. It is only immortal so long as it is wrapped in a temporal, live act, rather than a post-digital membrane, although the contents of the speech were oriented to a post-humanist company here as well.

The Metaphysics of the Runner, 2014. Display view at the CAC in Vilnius. Artnews.lt nuotrauka.

From the idea of cloning, a transhumanist’s household codeword, we move onto the most lucid post-humanist art approach (synthetically blueish like the Fiji mineral water flowing in the installation Crave that Mineral), recently cultivated in Lithuania by artist-duo Neringa Černiauskaitė and Ugnius Gelguda known as Pakui Hardware. The Metaphysics of the Runner, their debut exhibition in Lithuania which exhibited at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius between June 26 and August 17, 2014, became a symbolic starting point for this topic’s exploitation. They continue to emerge as important leaders among other contenders in this ongoing marathon.

Reflecting on human self-development aided by technology, and the anthropomorphisation of machines in their works, in the 2015 Kaunas Biennial the artists presented the aforementioned installation of objects connected by circulating minerals Crave that Mineral, but also their older piece from 2014, Shapeshifter, Heartbreaker, which works illustratively in this text as a field for growing and cutting mushrooms. It depicts a stock-market flash crash with synthesised 3D graphics that almost resemble yeast budding. The progress of technology that can replace humans is the regress of a certain factory of humanity, where the latter word functions only as an appendix or prosthesis.

Pakui Hardware, Shapeshifter, Heartbreaker, 2014. 3D motion graphics for 3 LED TV monitors, stock data from Bond Market Flash Crash (16/10/2014)

Mushroom seeds, discovered in 1792 through the lens of a microscope, were only called spores five decades later in 1778. Non-anthropocentric worldviews seemingly promise to solve a range of problems from financial crises, terrorism and emigration to climate change and genetically modified organisms. Meanwhile, art that is informed by science and technology, often taking early action, seeks to stimulate new sensual experiences and knowledge to activate and improve life. It will not be surprising if art – like synthetic mycelium akin to artificial intellect eventually surpassing the human mind – will begin to grow and evolve, thus diminishing us after we will have become historical pollution, and our original selves will have subsided into the Svalbard Global Seed Vault (located in the northernmost Norwegian archipelago) together with the eight hundred thousand other species of seeds, mushrooms and their spores, and the bacterial love letters we will have sent. But so far mushrooms keep growing, ecological consumption of art still calls for strict grading, and our diminishing selves unwittingly and increasingly turn into hikikomori (which sounds like the name of a Japanese mushroom) who prefer surfing the Internet, even in the case of this text.