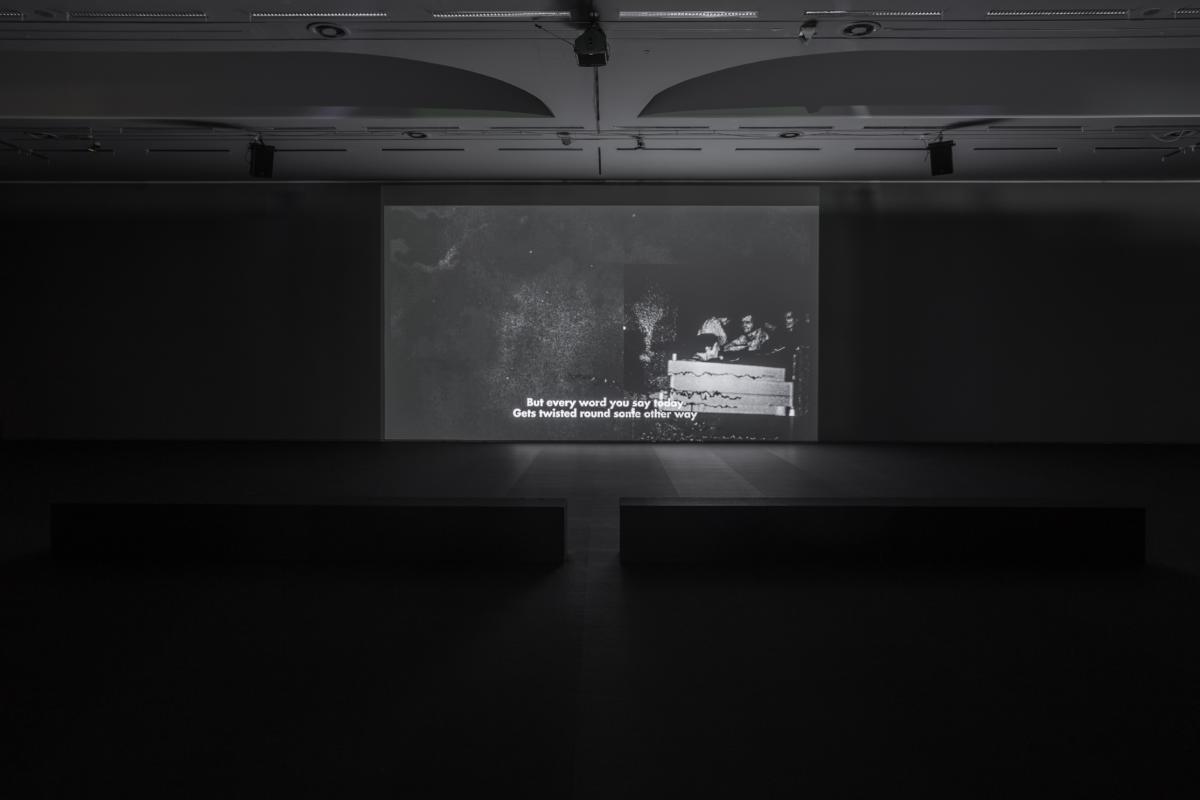

Deimantas Narkevičius, Stains and Scratches, exhibition view. National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2018. Photography: Andrej Vasilenko

‘Stains and Scratches’, a solo exhibition of video art by Deimantas Narkevičius, was presented in the 12th, the grand exhibition hall of the National Gallery of Art from 28 January 2017 to 25 February 2018. It was an integral installation, combining autonomous video stories shown in an isolated screening space, spectator interactivity enabled by stereoscopic vision, and audiovisual interrelations between the projections and separate soundtracks. The exhibition might be partially considered a retrospective of a long-lasting collaboration with the cameraman Audrius Kemežys. Gintaras Kuginis, the architect of the exhibition, was a member of the team of architects who famously designed the modern reconstruction of the National Gallery building. The contribution of the designer Vytautas Volbekas is also clearly discernible.

Bearing in mind Narkevičius’ artistic style, such complex integrity in an installation, consisting of separate video works, is an unusual approach. The artist is well known, and frequently recognised as a master of subtle, highly stylised, coherent compositions of unfolding narrative, by means of screen-based visuality. Looking back into the history of Lithuanian video art, in search of the canon that has formed over the last two decades, we could reasonably assume that such an artistic strategy has become next to iconic for video art as a definite kind of contemporary fine art, as it is perceived through the lens of the identity of the local art scene. Thus, from the perspective of characterisation by formal criteria, the exhibition ‘Stains and Scratches’ offers a certain dialectics of retrospective and première: it is not merely comprised of preceding and newer works, but is also structured as a system of meaning that integrates usual and unexpected modes of perception, in contrast, set off, and in counterpoint. Such eloquent tendencies were already manifested in Narkevičius’ solo exhibition ‘Sounds Like the 20th Century’, shown at the Vartai gallery in 2014.

However, sparing introductory remarks of a formal nature can be regarded as already preceded by this point, as the foreground of the so-called ‘artistic problem’ is taken up by questions that emerge with a much more striking significance: history and projection, memory and perception, representation and imitation, utopia and dystopia, threat and deterrent, manipulation and stratification, continuity and the ephemeral, the social and the psychological, discipline and the periphery, totality and deconstruction.

—

When you look through stereoscopic glasses, highlights gradually dissolve. Tension originates as condensed into trivial, hardly predictable potentialities. Admittedly, it is an artistic adventure. Obviously, another vertical citadel. The extension of darkness in an underground hall sets out reflections of stereoscopical jellyfish to dive through. Keep calm, it is probably just a hallucination. It is even likely that everything is simply normal here.

‘A subject’ that has been bitten by a jellyfishes nap in such a subordinated way cares little about grammar. However, it is naturally looking for a straw to grasp. Let us say, by recalling a debate on normality, explicated after a retrospective decadal exhibition at the Contemporary Art Centre. The foundations under the feet solidify insensibly, the hatch of a submarine in fighting trim opens up, and when a metal shell is already dropped down it is already possible to soak the flippers into a tousled mass of algae at the very bottom. A heavy concentrate of oxygen injects a clog of excessive imagery. The labyrinth of memories from the white cube subsides. The skeleton of structure thus reluctantly unlocks, and you can make an effort to surface out much more assuredly while upholding ledges.

Deimantas Narkevičius, Stains and Scratches, exhibition view. National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2018. Photography: Andrej Vasilenko

The stiffening trepidation of Orwellian apparitions is seemingly a ghostly substance, tending to return by causing a tête-à-tête of collective (un)consciousness with its own faded reflection. One may observe that monotony is objectionable to it, this chameleon that bears a toad-like pulsating tortoise integument, which has outlived each and every trace of time. It is quite difficult to tell whether it is a chthonic creature, or a wave of radiation emitted by a meteorite, ripped deeply into the ground. By quoting the DJ of one Russian radio, ‘Lenin is a mushroom and a radio wave’ (in Russian Ленин – это гриб и радио волна). The paranoia of the 20th century is breathing just behind your back in a persecuting manner, and one is not entirely sure if it is just another horror movie for instilled benevolent amusement at your mischievous disposal, or just another strain of blitzkrieg, camouflaged in a severely lengthy extension of time. In other words, it is always altogether the first, the second and the third…

—

Rhetorics isn’t merely an optics of perception. Rhetorics may stand as a tool. Instrument, to be precise. As an instrument it anchors what it represents. Anchors by concealing representation – as an instrument in instrumentary structure. When I see Lenin’s sculpture returning back onto a postament by the means of reversed motion of video tape (Deimantas Narkevičius, Once in the 20th Century, 2004), I’m witnessing an inversion. When I read a description of this inversion in a catalogue of an exhibition, I’m witnessing a validation of this inversion. I sense the weight of representation of the postament as it appears in different variations: flat space in Lukiškių square that alludes the absence of the monument, KGB museum nearby and torment chambers in a building, evolvents of industrial volumes, intertwingled perspectives in art exhibitions, that mirror these complex indications. I realise that I’m wandering in rhetoric thicket while being perfectly aware, that my experience is just a composite part of a dismantled sentence. When style is a category, it can be a rhetoric instrument as well as a tool of perceptive optics. Perhaps I don’t know what I want to say. In the same way I’m not sure how should I look at stainless steel in monumental projection through stereoscopic glasses. But when I’m dipped into a grimace of its’ heaviness, it seems I’m almost smelling it’s scent. It is diluted, constantly wimping out into periphery. Constantly returning back as if offhandedly.

In the world of representation, as well as rhetorics, it is often managed to confine with something, that could be called an index of reality or even truth of reality. In this light – especially under certain inertia within the active vocabulary – a problem of truth starts appearing so trivial, that gestures pointing out towards this blurred category unfold as almost anachronistic when judged by criteria, valid in the schemes of dominant discourses. In a publication, introducing Deimantas Narkevičius as a representative of Lithuania in Venice biennial in 2001, significant focus on the problem of truth is being distinguished. Here it is being articulated in relation with a dimension of historical memory and contours of social reality. Apparently, the horizon of such complicated reality is not by a long sight flat, observable with a naked eye, unambiguously negotiated or arbitrary under precedent conventions. Thus the questions of historical reflection and it’s method, role of the artist, meaning and value of his oeuvre are gaining primary importance. On the other hand, it is precisely where a distance appears and alienates a stylised narrative from documentary, factographic story, which might appear as ideologically influenced or, on the contrary, directly critical towards such influence. The more this stylized distance is sophisticated, the more it is difficult to grasp basic point of departure and localize vectors of active directionality.

In the exhibition such critical perspective becomes even more complicated when rational, analytical perception is being sharply contradicted by artistic engagement into a domain of mediated senses. It is a secondary stage of distantiation, that examines nearly all usual “institutions of trust”. Naturally, the effect is close to affect, while an effort to reconstruct certain integral, linear narrative is bound to drift through ruptures of meaning, inadequacies, slips of representation and tensions they provoke, tone and background that is constantly anxiously shifting. Such exposures imply certain logic of interpretation. It appears much more meaningful to start with an act of unfolding inner dialectics of “background in context”. And it is only afterwards, when a gesture of return towards the “external” scenario makes sense, as something immanently substantial has been lost somewhere along the way.

Deimantas Narkevičius, Stains and Scratches, exhibition view. National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2018. Photography: Andrej Vasilenko

Deimantas Narkevičius, Stains and Scratches, exhibition view. National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2018. Photography: Andrej Vasilenko

—

Video projection 20.07.2015 for a screen and stereoscopic glasses documents removal of the Green Bridge sculptures ‒ emblemic monument of Soviet period. Having in mind long lasting process of controversial debates concerning the destiny of sculptures, the fact itself took place in an astonishingly quick, operative manner: one day they simply disappeared from a city landscape. On this occasion another rather insignificant wave rippled through mass media without any exceptional uproar. If during the last weeks of July in 2015 you happened to cross the bridge by driving a car, riding a bicycle or taking a walk, you could somewhat surprisingly notice, that the usual place of sculptures was taken by huge monumental flowerpots (certainly, monumental in absolutely different sense of the word and to entirely different extent). Strange, unexpected turnabout.

The Green Bridge sculptures and their representation in the cultural context of dependent and independent Lithuania deserve a separate study. During the period of Independence, the monument used to evoke intellectual polemic on general topicalities encompassing historical memory and it’s traumas, nostalgia and reflection, psychological discomfort and it’s appropriation, symbolic signs of established power and dynamics of their reading from the perspective of cyclic, linear time or it’s discontinuity. In 1995 artists Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas interpreted the monument by realizing a conceptual, site-specific intervention into a public space: mirror cubes appeared on the heads of sculptures for a particular period of time (Coming Or Going?). A retro-colour postcard, that portrays the perspective of the Green Bridge by Arūnas Gudaitis (Vilnius Postcard Series, 2009) was chosen by curators as a representative image of X Baltic triennial Urban stories. An angle wasn’t by any means straightforward, but it appeared convincing enough: when you observe an urban panorama on the other side of the river from the Green Bridge bus stop, each time you’re facing a condensed encounter of distinct historical time. In the context of exhibition devoted to topic of “The Urban”, a postcard unpretentiously suggested casual invisibility of sculptures when seen from somewhere nearby and, almost paradoxically, their undeniable trace in the perception of urban topography even when you’re looking at the LCD screen shimmering above the Opera and Ballet Theatre (just in the neighbourhood of the Green Bridge) through the window of multistorey situated in relatively remote Šeškinė or Kalvarijos districts.

In Demantas Narkevičius’ installation this imaginary topography “in the shade of sculptures” endures. Though a presentiment, that subject of focus is not actually present here, doesn’t let go. It even appears, that the actual optics indescernibly and completely shifted somewhere else. Stereoscopic density interferes between the gaze and screen in a concentrically darkened exhibition hall by straining up an iris of the eye and nerves that roll the eyeballs. By reciting a song, written by famous Russian singer, “I feel your nerves tingling” (in Russian: „Я чувствую, как звенят твои нервы”). According the scenario ‒ at first, there’s a sunny dawn in a silent, absent, empty city. A fellow, as if in a reenacted “making of” session, jumps and claps hands in a somewhat puerile, emphatically pseudo-cinematographic manner. In the middle of the day ‒ passers-by gathering aruond in their summer outfits and lazy gapeseeding moods. In the evening ‒ the workers and their engineering tools for dismantlement show up, strangely accompanied by televisional outdoor studio rituals. Among these scenes, bearing a character of mundane documentary observing theatrical spectacle in a public space throughout a single day, attention of the viewer is periodically brought back to the main protagonists of the film: camera slowly depicts fragments of monumental sculptures, their solemn figures in an imposing close-up ‒ from their heavyweight feet to hammer and hook crossed in a sharp, rusted triangle of a flag tip. And then, obviously, a background ‒ fading in and blurring out in a 3D perspective. What disturbs here mostly is a hazy feeling that nothing is happening out there at the first sight. Or that something is just happening “as if”. In an exhibition hall of a Museum (which, actually, used to be “Museum of Revolution” before becoming National Gallery after Lithuania regained it’s Independence as a sovereign state) the act of observation of such an airy “grimace of representation” starts focusing on somewhat peripheral thickness. It’s symbolic load doesn’t invoke complementary commentaries, as it safely and persistently lies in isolated “margins of frame”, extending and spreading far out of sight.

Deimantas Narkevičius, Stains and Scratches, exhibition view. National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2018. Photography: Andrej Vasilenko

Deimantas Narkevičius, Stains and Scratches, exhibition view. National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2018. Photography: Andrej Vasilenko

Videofilm Stains and Scratches, that had inspired the title of entire exhibition, is composed of the episodes from Andrew Lloyd Weber’s opera Jesus Christ Superstar staged locally in the 80’s as a counter-culture event ‒ known little nowadays, although abundantly exceptional among youth audiences at the time of fait accompli. However, the sight hardly resembles a real staging. It is much more a concert variation of a rock opera. In the video-reconstruction of this rare footage, performers and audience are hiding in a shade of anonymity: names, the exact place and particular circumstances of the event are covered behind the folds of forgetfulness and secondary significance. Meanwhile the surface of the screen is being divided into a few parts: fragments of a concert’s video recording are diving into the surface of the screen out of a hollowness of deep, dark background. Soundtrack (the author is also unindicated ‒ supposedly, intentionally) for this videoinstallation not only fills the vast space in front of the projection, but also echoes in all exhibition hall (even outside).

The mosaic of video images is (a)sinchronically doubled by subtitles, approaching the viewer in a personalized manner. Disruptive logic of an imposed dialogue seemingly illustrates two-sided dialectics between the artist and the perceiver: open structure of meanings that shapes the exhibition is interferred by multiple layers, non-linear mediation, fragmentary extensions. It offers an allusion to Ariadne’s clew: it flirts, seduces, threatens and estranges by hiding in trivialities of external appearances, sensory inducement, counterpoints and tricks. Sequences of imagery visualizes the mirror of subconscious thus forming a retina of visible semblances on the screen: it nestles articulated insights. Self-reflection constantly witnesses the state of mediation in the dotted-line montage of this experience. Some kind of malevolence awakes in you when in a confrontation with a hushed up, anemic concert spree nauseous snottyness kicks in. You have no doubts that you could dedicate this genuine feeling to Andrew Lloyd Weber himself and real characters of the original version of the opera. It could appeal to him as a compliment, I hope.

Deimantas Narkevičius, Stains and Scratches, exhibition view. National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2018. Photography: Andrej Vasilenko

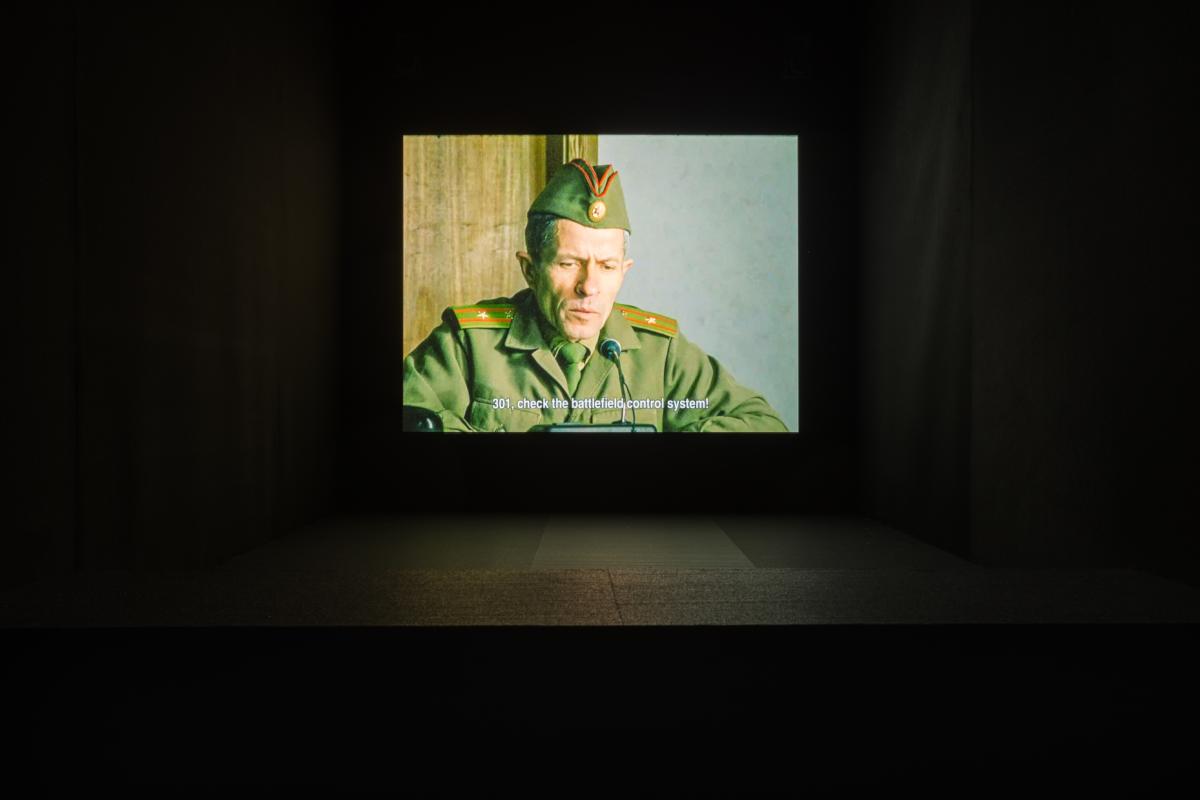

Video films The Dud Effect (2008) and Countryman (2002) were presented vis-a-vis in isolated black-boxes. First videofilm is foundering all the exhibition to the bottom of it’s weight as a submarine of military destination. The genre of a film is close to docufiction. Such an impression is primarily evoked by depicted environment that is accessible only to authors, having aspirations to purposeful research, inherent to investigative reportage or exploratory documentary. In this respect it is not the only, exceptional artwork in the context of Deimantas Narkevičius’ oeuvre. Videofilm Lithuanian Energy (2000) has to be mentioned here, as it portrays the environment of Ignalina (Eastern Lithuania) power plant. Revisiting Soliaris (2007), that is also exhibited in a solo show, borrows interiors of TV tower for it’s scenario. Though here the manner of artistic stylization is undoubtedly closer to fiction film than documentary.

In The Dud Effect we observe images of remote military zones, underground tunnels, bunkers, commanders’ offices. Several carefully chosen scenes convey a background for a story, articulated by allusions of an abstract character. One could assume, that film characters are real Soviet Army officers. Cinematographic portrait of a high rank officer could be excluded as one of the main motives in the videofilm. We witness a preparation for a launch of a bomb: when camera eye surveys visual field of a military zone, viewer’s gaze gets into an office, where the order is being released in Russian language by scrupulously fulfilling the procedure. Nevertheless, something in the film let’s us assume, that this military scenario stands for a metaphore here, an intensely suggestive image. The assumption is prompted by the title of the film, as well as poetic, dream-alike, slightly surreal atmosphere. Here we will not by any means encounter tensions of real gunfight event, turmoil of the battle, concentrated dramatism, historic or quasi-historic fatality. However, the “romanticism” of deserted military corridors and glows of the bomb, penetrating the density of an image, isn’t sentimental at all ‒ it simply can’t be.

A film Countryman, presented in a video-box in front, could make a counterpoint from a perspective of thematic approach. When we look at a bust of general Jonas Žemaitis ‒ Lithuanian partisan leader during the after war period ‒ that was built in 1999 near the Ministry of National Defence, we hear the monologue of the author of the monument, sculptor Gintautas Lukošaitis. But the emphasis shifts towards the sphere of personalized “minor story”. Character of a sculptor unfolds as a vulnerable personality, who is affected by conjuncture peripeteas, competitive topicalities, mundane routine of creative work. Bust of the general, who is now officially regarded as the fourth President of Lithuania, is silently looking at us with all his rigorous greatness from, supposedly, sculptor’s studio. It feels like author’s monologue polishes the stone of monument, expressively black, and warms it up by husky, unassured, slightly confused, doubting voice. Perhaps this is the reason why the monument also starts vividly reflecting stiffened lineament of Jonas Žemaitis face, demandingly recalling factographic and photographic memory, which brings back a real image of historical personality.

In the second part of film Countryman we hear silk voice of light-hearted, though mundanely elegant coquette. The heroine is portrayed as if in lantern slides, in a plot, assembled out of stop-motion images. Almost forgotten sensitivity of observation and self-reflection unfolds as cinematographic eye intervenes in a video-genre manner and starts unnoticeably fusing monumental formality of cinema. Nostalgic colouring and tonality reminds retro-aesthetics of TV, but is much more intimate. Fragile distance is explicated by evidently flirting, as if tiptoeing yarns of voice-over monologue. Structured as a quite peculiar triptych, film ends up with panoramic landscapes and fragmentary scenes from Vilnius Old Town, accompanied by romantic symphonic motives by Richard Wagner. A time flow of a videofilm starts shivering like crinkles of tight thin cloth, distinguishing retrospectively it’s every slightest detail.

Revisiting Solaris, supposedly, might be considered as a film, which is critical to open up a conversation about the exhibition or distinctive enough to sum it up. A legendary Lithuanian actor Donatas Banionis plays part in the videofilm, created as a contemporary interpretation of Solaris (1972) by enigmatic Soviet director Andrei Tarkovsky, based on Polish science-fiction writer’s Stanisław Lem’s novel. Donatas Banionis famously played a role of main character Kris Kelvin in the film ‒ unduobtedly, one of the most significant roles in his entire artistic career. A period of thirty five years separates these two roles in two films: cinematographic masterpiece by Andrei Tarkovski and it’s interpretation in a highly subjective videofilm manner by Deimantas Narkevičius. The actor revisits and reactualizes his own autobiographical memory in a fictitious frame of the story, that artist conveys as a contextual paraphrase, full of cultural references, connotations and subjectivities. The plot entangles several visual narratives. Landscape photographies, made in the beginning of the 20th century by famous Lithuanian painter and composer Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis are being shown in a cinematic fashion, snowy descending hills and meanders of the river resemble misty giant waterfalls. Interiors of TV tower become a scenery for theatricalized action. The artist himself and his wife show up as film characters. One can easily notice, that several rather simple solutions in cinematographic approach uncover unfathomable range of the 20th century memory and imagination. Thus the appearance of real personalities, conditioned by specific everyday time in temporal moment of history and inevitably stencil imagery, seems quite grotesque in a space of modern mythologies (or marked by their loss and absence). Vast horizon, portrayed in one of the scenes (reminiscent of horizon photography by Hiroshi Sugimoto, exhibited in the same hall of National Gallery within the frame of an exhibition Million And One Days), seems much more likely to witness presence of desolate distance rather than signs of time, filled by traces of experience. Projection screen was hung just under the ceiling of the exhibition hall and is possible to view only on the ground floor from the perspective of a “survey balcony”, that is originally designed for a “birds eye view” to the 12th hall of National Gallery, situated below. It is apparently an emphasis, that consciously spotlights ephemeral nature of video time and makes it obvious.

Deimantas Narkevičius, Stains and Scratches, exhibition view. National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2018. Photography: Andrej Vasilenko

Deimantas Narkevičius, Stains and Scratches, exhibition view. National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2018. Photography: Andrej Vasilenko

Regardless the fact, that the title of the exhibition coincides with the title of a videofilm Stains and Scratches, meaning of the keyword itself has not yet been revealed. Presupposedly, the relation of time, appearance, memory, experience to materiality might partially clarify a title, that is not subjected to direct unambiguous logic. It is worth to remember that video medium was discovered by Deimantas Narkevičius only after he gained his academic background and artist’s recognition as sculptor. In the permanent exhibition of the National Gallery, in exposition of collection of Lithuanian art in 90’s, an object Too Long on a Pedestal (1994) by Deimantas Narkevičius is being presented. Object consists of a standart pedestal (museum’s ready-made) and a pair of leather shoes, filled with salt. The object insensibly engages in conversation with Deimantas Narkevičius’ solo show Stains and Scratches by accumulating connotations of artworks in neighbourhood of museum’s collection, architectural volumes of exhibition halls, unfolding time evolvents, tangible materiality of permanence in form. After all, radiance of a screen or pressure of sounding oscillations at the “bottom of the exhibition hall” cannot be at any effort put on a pair of scales together with shoes and two piles of salt. It is probably much more wise to rely not on the expression of a stain or precision of a scratch, but genealogy of meaning, recognizable through them.