This interview took place in June during a record-breaking heatwave in Tallinn. In the background of this brain-slowing temperature I sat down with the team of Tallinn Photomonth: Laura Toots, artistic director, and managing director Kadri Laas. We talked about the historical legacy of the event and this year’s programme, an expanding approach to photography, a need to constantly revaluate what we focus on, how we can slow down and reflect, and some of the global conditions of image-making today.

Paulius Petraitis: I would like to start with a long-winded question. The director of the first Tallinn Photomonth (2011), artist Marge Monko, recently stated in an interview that the very title Photomonth has to deal with the problematics of the word “Photo” contained in it. The tension seems to come from what the word defines and which avenues it opens and closes. I think for someone from outside, quite a usual reaction coming to one of the Photomonth’s exhibitions is that of a surprise because they are confronted with works which have little to do with how photography has traditionally been defined. Could you speak about this relationship, and why it is important to have an open definition of photography?

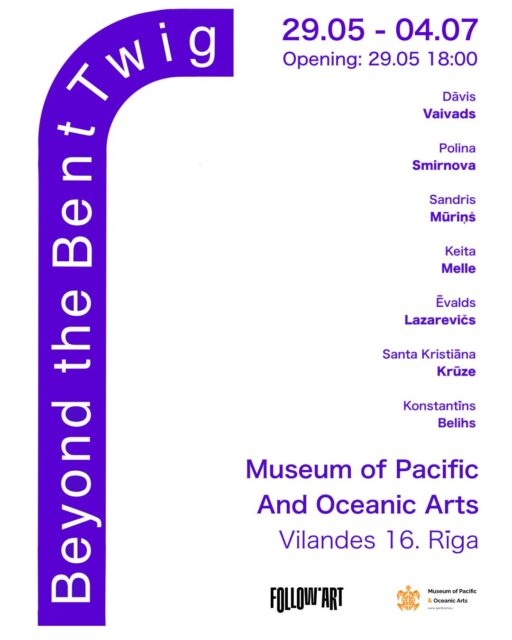

Laura Toots: The Union of Photography Artists (Foku), which is behind the Tallinn Photomonth, was founded in 2007 by ten members who were mainly linked to the Department of Photography at the Estonian Academy of Arts (EAA). It was a like-minded group of colleagues, and their idea was to promote photographic art next to printmaking, painting, and sculpture – artistic practices which have historically been more acknowledged as such. With Tallinn at the time about to be one of the European Capitals of Culture, the idea was to join energies and minds for an international event in 2011. This is the legacy. The name has also been kept to reflect that. At that time, one needed to promote a wider recognition of photography as art.

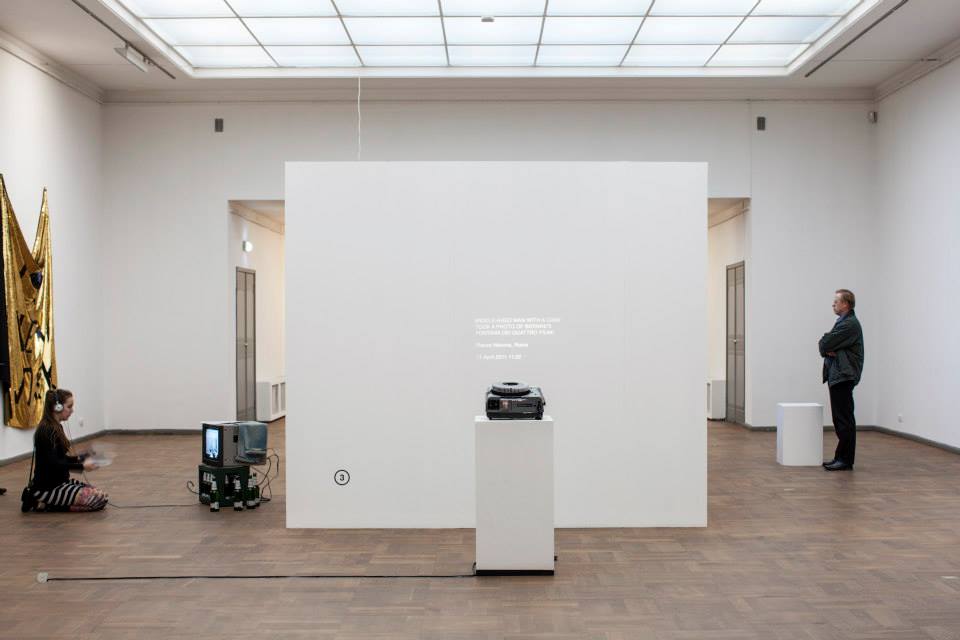

Kadri Laas: It was also related to discussions that Western Europe had already decades ago, that photography is a form of visual arts. All Tallinn Photomonth biennials have promoted this attitude. The first main exhibition in 2011 at Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn was an international contemporary art show that brought forth artistic positions concerned with the use(s) of photography, but blurring the borderlines between forms of expression. Visitors could see photography in a way that was new to local audiences: works in new formations, placed in an experimental way in the space, and maybe most importantly, made to escape set categories of how the medium has traditionally been defined. This situation allowed us to challenge and think about definitions of what photography is.

LT: The members of Foku had also had incorporated film, video, sculpture and spatial interventions into their works – an interest that was also passed on from this organising body to the Tallinn Photomonth biennial. Therefore, since the first edition of the biennial in 2011, the artists and curators behind it have felt the need to broaden the boundaries and rules of photographic art. The necessity to think more broadly about the term “photography” has become more inevitable in the world we live in, which is mediated by screens and cameras. Everything is photographic.

KL: The expectations by the visitors hoping to see something else – you are right, that is there. Sometimes it’s a more clearly expressed reaction, sometimes more a discussion formed by an understanding why is it like this. When we approach international curators and invite them to propose projects for the biennial, this is something we ask them to consider. The received proposals have been very interesting – what is photography nowadays when we are talking about screens in a wider sense, cameras and scanners with unimaginable capabilities, or jpegs as an integral part of society?

Marge Monko’s installation Flawless, Seamless on Freedom Square, 2017. Photo: Kristina Õllek

PP: This is perhaps symptomatic of the global shift in how photography is understood and functions. We acknowledge that photography has changed, but it is also changing and will change. We need to constantly update this idea of what photography is, what it entails, where its limits and boundaries stand. What’s interesting for me, and what I find valuable, is that Tallinn Photomonth tries to tackle these rather difficult questions. The “Photo” in the name feels a bit like an anchor, but it is important to ask what photography’s legacy is in 2019 and what ways we have to talk about it, to open it up. For us in Lithuania the situation is slightly different, since we have a strong tradition of a long-standing and influential school of humanistic photography. It still forms our thinking. I think compared to Estonia, the idea of classical photography is more strongly ingrained into our cultural fabric.

LT: I agree. Artist Eve Kiiler, who was one of the people behind photography curricula at EAA, has said a similar thing. The move towards more critical and conceptual photography in the early 1990s was possible due to the adventurous attitude of not having traditional teachers. Applied photography education existed already before, but as a degree – at Tartu Art College and at the Estonian Academy of Arts – it’s only 20 years old.

KL: When we discussed whether to keep the word “Photo”, we added the subtitle “Contemporary art biennial” for clarity. But we also kept the main title for the discussion to still be present.

PP: Tallinn Photomonth is a special photography event in the Baltic context not only in its expanded approach to the photographic discourse and image-making, but also that it is consciously reflecting and positioning itself within the field of contemporary art.

LT: The Department of Photography at EAA has trained a lot of people currently active in the contemporary art field. Not only as artists, but also as curators, programme directors, project managers, etc. Marco Laimre, who ran this department during 2005–2017, has said that having “photography” in the name was mainly to distinguish it from other departments in the academy, otherwise he would have called it “Department of Contemporary Art”. As I studied in the same department, I’m also keen to continue working with this interconnectedness and feel comfortable in this relationship.

KL: It is inspiring to think about artists graduating from the photography departments without making any photos at all, just like there are sculptors who make no sculptures and painters who have no paintings to show. The need to expand one’s world and practice is very present. It also seems to be a wave of discarding the labels as “photography”-artist and “installation”-artist as well as the specific divisions in the art academies where the trend seems to be more open to general visual art programmes.

The core team of Tallinn Photomonth 2019 with curator Heidi Ballet. From left: Kulla Laas, Kaisa Maasik, Heidi Ballet, Laura Toots, Kadri Laas, Sille Kima. Photo: Helen Melesk

PP: 20, even 10 years ago, the focus of critical discussion around photography was its malleability and manipulation. A few years ago a prominent strand in these discussions was the unprecedented influx and abundance of images, which was also reflected in your opening exhibition in 2017 called “Image Drain”. Working with this year’s programme, what do you sense is the focus? Do you feel that we have, to an extent, accepted the situation that we live in a world full of images and are moving on to other issues?

LT: We seem to have accepted the situation and are now thinking about navigating and surviving in this abundance, as well as related policy-making on various levels. This year’s programme brings forth some of these strategies. For Heidi Ballet, who is the curator of the opening exhibition at EKKM, the focus is on the environmental issues. Matthew Post together with Simon Dybbroe Møller work with the development of technology discussing images and objects and routines that are not photography but are photography-like.

KL: The latter exhibition, for example, also talks about photos being sleeping data on the phones that are continuously taken but never looked at. The abundance of images and other data are still important topics – information existing and not existing at the same time. The third main exhibition at the new Kai Art Center, curated by Hanna Laura Kaljo, offers a recovery from that intense world by presenting artists whose practices span visual art, meditation, contemporary dance, writing, and traditional medicinal knowledge. As our lives are so busy, winters are dark, information so abundant, and everyone expects us to do so much, the question is what to do with that? How to navigate, to cope and survive?

LT: Maybe we should slow down or even hibernate during winters to be more in connection with natural processes around us, to be more us. I have started to pay attention to it much more since working together with Kaljo and analysing her focus on receptivity, to our bodies and our surroundings. The flood of information has alienated us from each other for such a long time and to such a degree, that now we are looking for closeness with each other. And for the ground under our feet. If nature and our bodies tell us to take a break or slow down, we should listen.

PP: That’s an important point. You are running the biennial together for the second time in a row. How are you approaching this Photomonth and its programme?

LT: This year’s programme skips the satellite town that we’ve had for 3 previous editions. We aim to be more compact in order to have thorough discussions with artists and curators, as well as collaborate more closely with institutions we work with. The goal is to have more dialogue. With the curators’ first site-visit in January we hoped that they would already cross-pollinate each other – be aware what others are working on and propose events for each other’s exhibitions.

KL: In 2019 we have three international exhibitions at three different venues in Tallinn, by the abovementioned curators. The main programme of this year’s Photomonth opens gradually on consecutive Fridays throughout September. The last week of the month is the Professional Week, when all the shows will be open, art fair Foto Tallinn and specially programmed networking events take place. The series of three screenings of artist’s films, curated by Ingel Vaikla and Jesse Cumming, takes place at the cinema Sõprus in Tallinn Old Town. In October the public and educational programme will be emphasized. On top of that we have a satellite programme, with 18 independent events, varying in size and duration, taking place in Tallinn.

PP: What is interesting about the Photomonth is that not only is it artist-initiated and lead, but also that its leading persons change. After Marge Monko was the director in 2011, Kristel Raesaar led the biennial in 2013 and 2015, it was you for 2017 and also for the upcoming 2019 edition, stopping there. What do you think this rotation does and how this process affects the programme?

KL: The rotation is not an established principle in itself. But until now it has happened that no director(s) has taken on more than two Photomonths. I think organising any big event repeatedly has pros and cons; but it definitely needs fresh ideas at some point. At the moment we have ideas for the next Photomonth, but I consider it a healthy decision to pass it on now when everything is still stimulating.

LT: I also think rotation of people and ideas makes it simpler to react to current times. These revisions have helped the Photomonth biennial in many ways. It adds flexibility, intimacy – it is an organization, but then again it isn’t.

PP: Yes, I’m thinking if that also contributes to the expanded approach to the notion of photography. As people are changing maybe there is less of a habit for a certain pattern of thinking to set in, as each person or team brings a different background with them. Photography, as a traditional medium, is still an important part of Marge’s artistic toolbox, while Kristel has her own different profile. And you have your own background and other jobs – Laura you are working as a curator at EKKM and Kadri at the Estonian Contemporary Art Development Center. Thus perhaps each person or team adds something to this understanding of the definition of photography that the Photomonth displays, making it pluralistic and more like a dialogue. So the approach becomes polyphonic, which for me is a strength of the Tallinn Photomonth.

KL: Yes. And in addition to the team’s understanding and approaches constantly changing, Photomonth has always invited guest curators for fresh blood and ideas. In 2011 Adam Budak and Vytautas Michelkevičius curated the main exhibitions (at Kumu Art Museum and Tallinn Art Hall respectively), in 2013 it was Niekolaas Johannes Lekkerkerk (Tallinn Art Hall), in 2015 David Raymond Conroy (EKKM), in 2017 Anthea Buys (Tallinn Art Hall) and Stefanie Hessler (EKKM).

LT: For us it is like a playground, where we constantly inviting other “playmates”– curators and other collaborators – to have a dialogue. Enjoying ourselves in the constructive process has been important.

PP: This being the fifth edition and tenth year of the Photomonth, do you feel there is a need to step back and reflect what’s accomplished?

LT: Definitely. It is something we should make time for – to reflect and to ask, what did it give me, what it gave to the art field, friends and colleagues, what new acquaintances were made. It’s not that it’s an anniversary year, I think taking time to review should be a regular part of our actions, also in everyday life.

KL: I agree. We are not only stepping back, but also stepping away from the Photomonth after this year’s edition to pass on the chance to work with what’s been built so far, and more importantly, ask a question – what would a contemporary art biennial be and what does it need in 2021?

Heidi Ballet and artists in conversation, the opening of Tallinn Photomonth at EKKM, 2019. Photo: Helen Melesk

Ingel Vaikla introducing the opening screening of 2017 film programme Imagining places at Sõprus Cinema. Photo: Kulla Laas

Main exhibition of Tallinn Photomonth 2011 – Beyond at Kumu Art Museum. Photo: Karel Koplimets

Main exhibition of Tallinn Photomonth 2013 – Shadows of a Doubt at Tallinn Art Hall. Photo: Kristel Raesaar

Main exhibition of Tallinn Photomonth 2015 – Prosu(u)mer at EKKM. Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

Laura Toots and graphic designers Jaan Evart and Ott Kagovere planning the display vitrines for the opening exhibition at EKKM, 2019. Photo: Helle Ly Tomberg