Euroland, exhibition view, Temnikova & Kasela Gallery, 2017

Europeans tend to think of cities, especially those that stand out with their urban landscapes, as battlegrounds of fictitious powers, cunning politicians and nefarious business moguls. With compelling speed, gentrification policies eat up smaller and larger neighbourhoods, so far turning numerous undeveloped areas into new business hubs or hipster realities. Although artists play an equal measure in contributing to the process of gentrification, often moving into poorer areas, the question is how, instead of aligning themselves with the institutional powers, can the art realm respond to this situation, themselves being active participants and shapers of the city and its image? In light of the growing crisis and criticisms surrounding neo-liberal systems and even democracy itself, the very foundations of these Western paradigms are being increasingly questioned. For a long time, Europe has regarded itself as a common ‘land’ or ‘forum’ that everyone now undeniably finds in crisis. The exhibition Euroland poses difficult and uneasy questions that resonate with the complex and troubling times Europe is undergoing – how can artists, and non-artists alike, approach urban city spaces and life that has been shaped in Europe and Russia after WWII? Do we have to accept institutionalised discourses in our lives, and what kind of response can we offer?

Euroland brings together artists representing various countries, cities and contexts (Moscow, Berlin, Vienna, Tallinn, etc.) offering different perspectives that speak about the issues raised by the exhibition’s conceptual idea. Each offers their own artistic method, which at first glance might seem incompatible, but together they nevertheless form a unique dialogue. The main, and most noticeable, points of reference in the exhibition are Tõnis Vint’s graphic art series made between 1971 and 2001 and Juhan Soomets’ sound installation The Artist’s Room (2016).

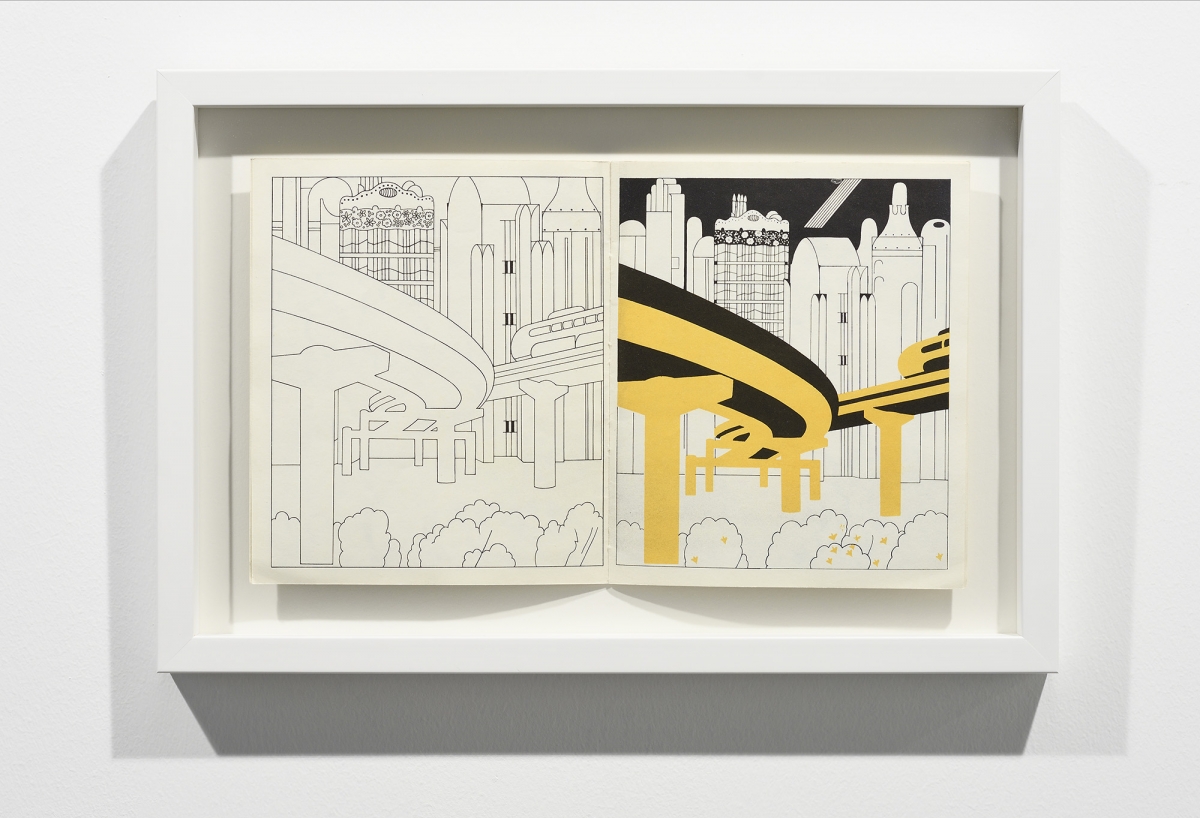

Tõnis Vint, Into the Year 2000, book illustration, framed 1973

Vint, a classic in the Estonian art world and a representative of the Estonian school of architecture, famously developed a minimalistic, abstract and graceful language of lines outlining urban structures that project the contours of a future city, or desired city. He was the first artist in Estonia to accent the “empty space” concept – the idea that emptiness is not non-existent; instead, it is the beginning of all ideas and forms. This can be observed in his series of work presented in the exhibition, in which imagination is conjured only by means of lines and contours, thereby dreaming up a city full of hope, and attractive to its residents; a beautiful city that is responsible. These romantic projections and images that were brought to life by artists in the Cold War era were incongruous with the realities they endured at that time and what came later. One could have labelled these projections as escapism, but they also contained a kind of freedom of thought that was provided precisely by the language of architecture. While Oleg Frolov, the exhibition curator, states that “… Vint’s experiments signify the institutions of a bureaucratic and meritocratic state and rather symbolise a quest by a European, robbed of his identity, than an attempt to find a universal artistic language,” this is a statement I cannot fully agree with. During the Soviet era, architecture, urban town and city planning were fields in which artists could dream; they could realise ideas that were not necessarily allowed in the field of visual art. In the context of the Soviet system, this was a window to align oneself with a European language whilst also preserving local authenticity.

Ekaterina Borsuk, Roof, 2016

In a way, Russian artist Ekaterina Borsuk’s colourful, small-format drawings depicting the industrial face of Moscow and other large cities stand in opposition to Vint’s work. Her scenes are almost abstract, because it is impossible to clearly define what it is that we see in them exactly – whether it is a fragment or corner of a building, rooftop, electrical wiring, or something else which can often be seen in the foreground set against a red sky. The contrast of bright colours and the clumsy, robust drawing creates a slightly apocalyptic, even unrealistic, impression. In the context of the exhibition, it might be possible to read the drawings as a deconstructing message about the city and its institutional powers, which are on the verge of decline. But at the same time, this urban melancholy also seems a bit naïve and romantic, and in this sense the drawings are similar to Vint’s work, differing only in language and expression.

The uniting piece in the exhibition is Juhan Soomets’ interactive sound installation, which viewers discover on their own by touching lines that cartographically connect all of the works in the exhibition into a single tangle of sound. By rubbing one’s fingers against the aluminium lines running along the walls of the exhibition space, a variety of sound compositions can be created. In turn, these different sounds create a sort of ambient atmosphere for the whole exhibition and also a theme for it, in a way. Frolov compares it to the “micro-economy in the city which relies on certain technology, clever positioning, and employs people’s emotional and cognitive capacity”. But Soomets’ work is also like a playground or an instrument, with which one can work; it does not anticipate specific outcomes, only possible scenarios. This work of art can be perceived as a fairly precise metaphor for systems that are directed by ‘invisible forces’ or have been programmed. But deviations are in fact possible within any system, even the most precise system, and maybe that’s what this installation is about? Soomets’ work is in some way related to Leopold Kessler’s First Tallinn Dog Picnic (2017), which also tells about centralised institutions and systems that anticipate specific types and patterns of activity and results – in this case proving his point with a dog’s behaviour.

I also see an echo of Soomets’ work in Swedish artist Klara Lidén’s video Untitled (Trashcan) (2011), which portrays an office-like atmosphere in which nothing particular happens, except that the artist suddenly decides to climb inside a wastebasket and ‘fold’ herself into it completely, thereby disappearing from the view of the visitor or camera. This art work can be read in two different ways: as a commentary about the public and private, the individual and society, the artist’s creativity and the frameworks and values imposed by institutions. In this case, the wastebasket serves as a powerful symbol pointing to a specific matrix of power in which all of us must fit. At the same time, it can be interpreted very directly as a place for ‘leftovers’ – but leftovers of what? What exactly are we squandering in our current crisis of democracy?

Denis Stroev,Casing: The Head of Saint John, 2013

It’s possible that Denis Stroev’s work Casing: The Head of Saint John (2013), which tells of the loss of humanism in contemporary society, answers this question quite directly. The installation consists of a carefully made brass frame supposedly holding an image of Saint John, whose face has been ‘cut out’. I can agree with the curator on this one, that the face here is like “a symbol of rational and moral values”, and that the frame is like an indication of “technological and military apparatus as well as an educated bureaucratic class ready to implement the cruellest of policies”. Like a ghost, this work of art precisely reflects the political crisis as well as the feeling in Europe and beyond of impending war.

Euroland also includes a work by the curator himself, Frolov’s sculpture/installation Anti-War Monument (2017). It consists of a pile of objects resembling large bird houses, in which the house-like form has become something of a face with two holes that look like eyes and a peg for a nose. This imitation of a face even has a blue tear drawn on it. Each little house sits on a pole that has been broken off. Taken altogether, the scene is quite sad – it’s as if these objects have been thrown out and no longer are of any use to anyone, hence they’re grieving. Frolov’s work is a powerful metaphor for the war that he calls the unceasing war (in Russia) which has already been lost. The imitated faces in his sculpture reflect not only vulnerability and sorrow but also the helplessness that dominates contemporary society, which is incapable of engaging in political discussions and critiques of the rhetoric used in those discussions. The curator’s installation can also be viewed as a comment on the exhibition he has created, which supposedly plays on and stimulates viewers to think about the forms of ideology in society today, especially in the context of the crisis of democracy, but which are at the same time restrained enough to create a definite sound. Here, we must return to Soomets’ sound installation once again. It lights up and creates a humming sound in people’s heads for a certain length of time, but then it disappears again after a short while, waiting to be discovered anew by the next person. The dynamics of passivity that can be observed between the works of art in this exhibition are definitely the best and most precise comments about the theme presented by the exhibition itself.

Euroland, Temnikova & Kasela Gallery, Tallinn, Estonia, March 18 – May 6, 2017

Curator: Oleg Frolov

Artists: Ekaterina Borsuk (RU), Leopold Kessler (DE), Klara Lidén (SE), Juhan Soomets (EE), Tõnis Vint (EE), Denis Stroev (RU), Oleg Frolov (RU).

Photography: Temnikova & Kasela Gallery

Euroland, exhibition view, Temnikova & Kasela Gallery, 2017

Tõnis Vint, White clouds II, 1971

Euroland, exhibition view, Temnikova & Kasela Gallery, 2017

Oleg Frolov, Anti-War Monument, 2017

Euroland, exhibition view, Temnikova & Kasela Gallery, 2017

Euroland, exhibition view, Temnikova & Kasela Gallery, 2017