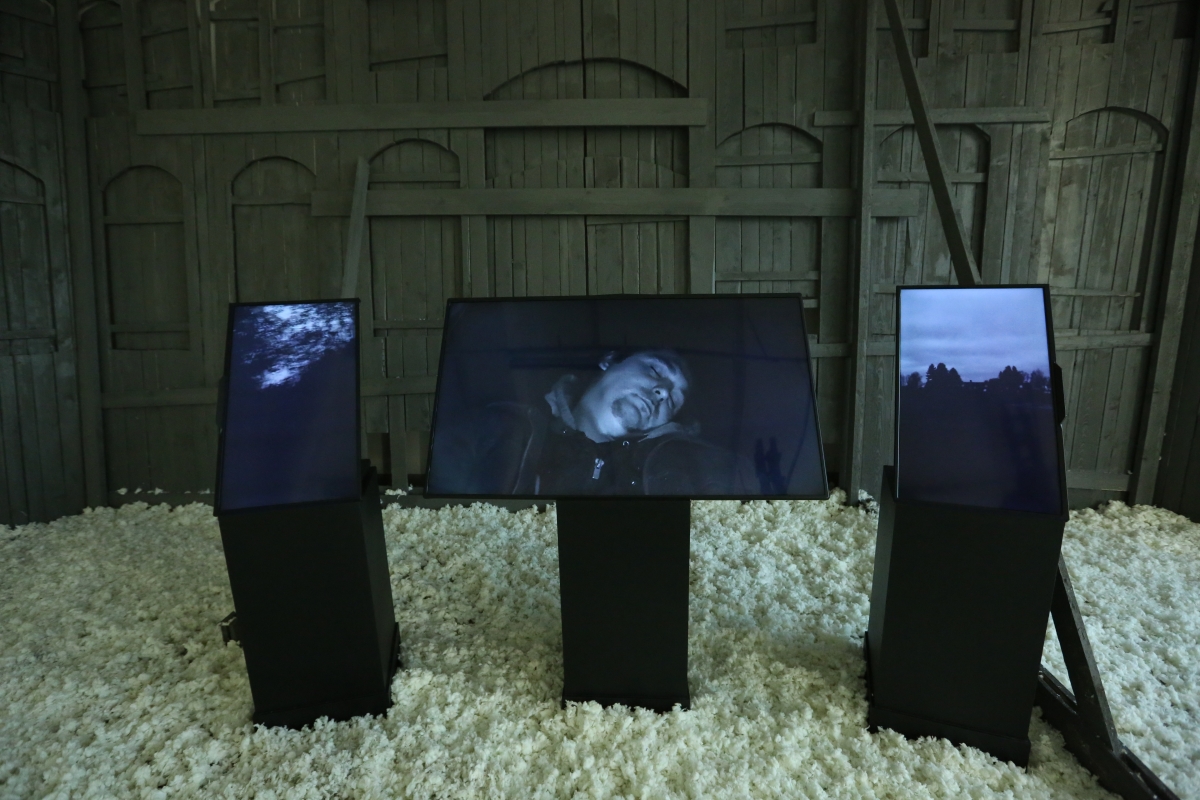

Javgeni Zolotko “Foundation (I)”, installation, 2016. Photo: Annika Haas

Often when intense fall commences and autumn enters its darkest days and nights, many towns and cities across the world embark on celebrating the festival of light. In October and November in Latvia, this period of contemplation is also known as the silent days of God (Dievs) or ‘Dievaines’ in Latvian, meaning ‘Time of the Dead’. The ancient Latvians believed their dead ancestors, draped in a coat of fog, would tumble by and help them find answers to different questions posed by the living during this time. Those who have experienced at least one festival of light will understand that this event is not dedicated to any such contemplation, nor does it revere the sun like on the summer solstice (Jāņi Day). Rather, it encompasses artistic attractions and makes use of visual effects instead, demonstrating the latest trends and possibilities in LED lighting and video projections.

If we are to look back over history, we can see that the idea behind the ‘festival of light’ is not so far removed from the light shows created during the ‘dark’ Middle Ages. In this period, they worked on creating kaleidoscopic rosettes and stained glass windows of gothic churches which would be illuminated by sunlight. At the peak of Rococo during the Baroque period, they fashioned dazzling gold interiors and at the peak of the sweet Rococo through combining the use of mirrors with these reflective gold properties, they could achieve incredibly illusive room enlargements. Ultimately, when the light bulb was conceived during the period of the industrial revolution, a new wave of electromagnetic rays were consequently produced which are nowadays referred to as light pollution. However, the purpose of light has always implied something other than simply having a physical or decorative function. In the Middle Ages, the role of the stained glass light effects in churches were to create a sense of presence of the divine light, while in Baroque times, gold also represented wealth and authority in addition to this divine light. With the advent of the Enlightenment in European culture, light eventually became a metaphor for mental vigorousness and the development of critical thought.

This year, when the festival of light had finally reached Tartu after a prolonged break and Estonian artist Tanel Rander had emerged as one of its most unexpected organisers, it became clear that these events would surpass the aesthetic properties of light and the technological possibilities of projections. Instead the light would be politicised and shone straight into the faces of the audience. Rander’s project with its messianic title The Promised Light consisted of an exhibition in two parts: an installation by the Tartu-based artist Yevgeni Zolotko at Galerii Noorus and an international group show at Tartu Art House, which brought artists together with art historians and social activists. Both exhibitions represented darkness and light as metaphorical terms to talk about the up and down sides of power relationships between individuals, countries and cultures.

The selection of the works to be exhibited seemed unfinished; instead they more served as representatives of the issues currently important to the organiser and therefore became a platform for Rander as a socially active artist rather than an elaborately calculated exhibition put together by a curator. Each of the artworks exhibited acted as counterpoints, questioning the legitimacy of ideals created during the Enlightenment against that of our reality in the 21st century. For instance, the sharply ironic video work by Turkish artist Berat Işik Dancer in the Dark (2003), explored how thousands of individuals and nations who, depending on their global positioning of power, could be made anonymous and have their ability to be heard or noticed taken away from them. As such, the video shows complete darkness interspersed with a voice desperately trying to attract our attention. The right to be heard is similarly important to the work by Kaunas-based student collective and activist organisation Aukštasis Moxlas who staged several public protests against Vytautas Magnus University in 2014 and 2015. Aukštasis Moxlas criticised the higher education system for being more concerned with profiteering from students than ensuring their protection and qualitative education. In their eyes, students entered a system resembling a Saṃsāra wheel that was ruled by creditors, borrowing loans which they would inevitably have to repay through working in some factory in Great Britain or Scandinavia. Various materials from these protests were exhibited as a post-factum testimony including placards which copied the design of the Lithuanian supermarket chain MAXIMA, and a lottery wheel which determined future employment places of students.

As a left leaning exhibition, it became clear that what was being illuminated was the relationship Western civilisation had developed with consumerism. Here, Austrian artist David Kellner’s animation could have been used as a promotional video for the exhibition itself. Based on antique myths that had been transported from the past into our modern-day context and society, The River (2012-2013) spun a symbolic narrative about the river of life and death dictated by financial systems. In Kellner’s story, Death features as a boatman collecting money from an endless queue of people who can afford to pay for his service. Meanwhile, those outside of this finance-driven system and relationship end up drowning in the river of anonymity.

Another transit ‘river’ is also depicted in the work Message: 147 of 494 (2016) by the Estonian artist of Latvian descent, Diāna Tamane, who continues to portray her family in line with her previous projects. Tamane, whose parents work in trade and specialise in transporting goods along various routes between Eastern and Western Europe, represents this by creating a wallpaper-like photographic portrait of her mother as a truck driver and a collage assembled from her father’s amateur photo album of sellable goods meant to be traded through the internet. In the context of this exhibition, Tamane’s work acquires political and social overtones putting in the spotlight several Postsoviet condition based issues as for example change of the market and consumerism tradition, including import export strategies between the West and much more cheaper sales platform and travel lines of East Europe. Or gender based issues as female experience being the track driver for the international logistic company. However, in my opinion, her actual aspiration is simply to present personal narratives leaving the tricky relationship topic between the former West and East Europe block to become nothing more than just a background.

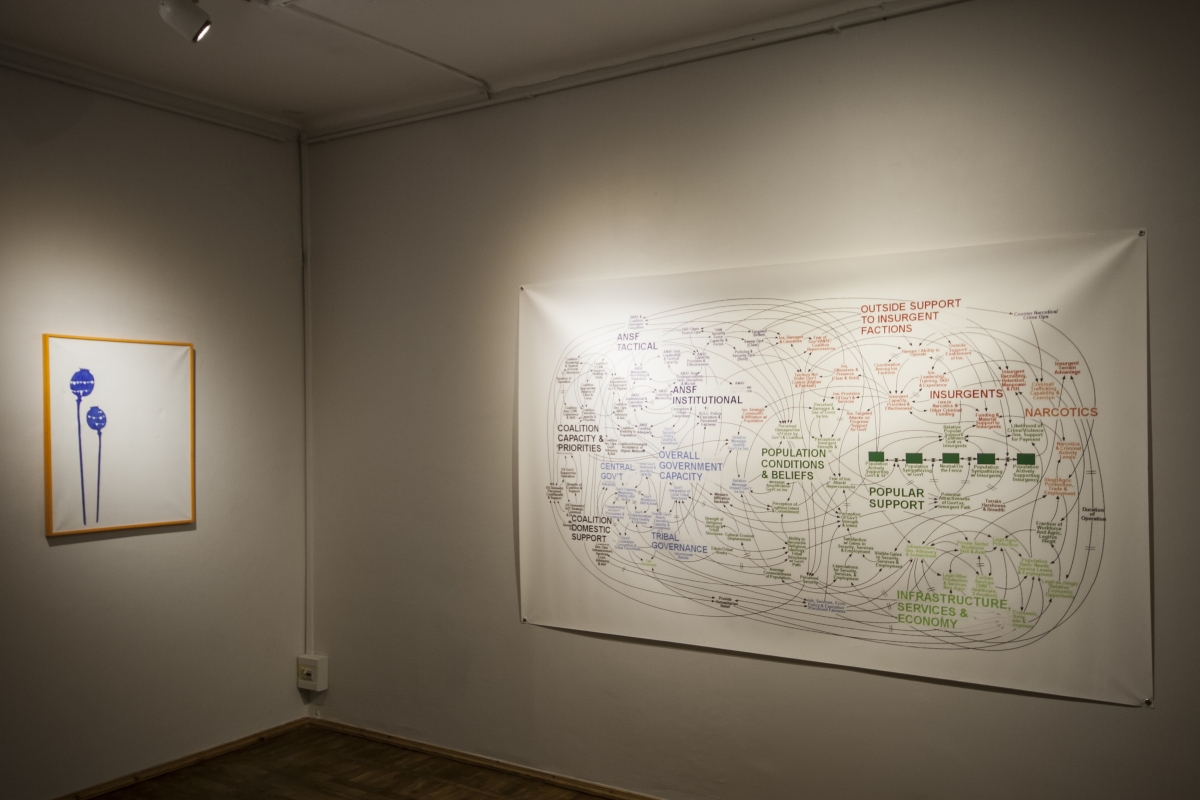

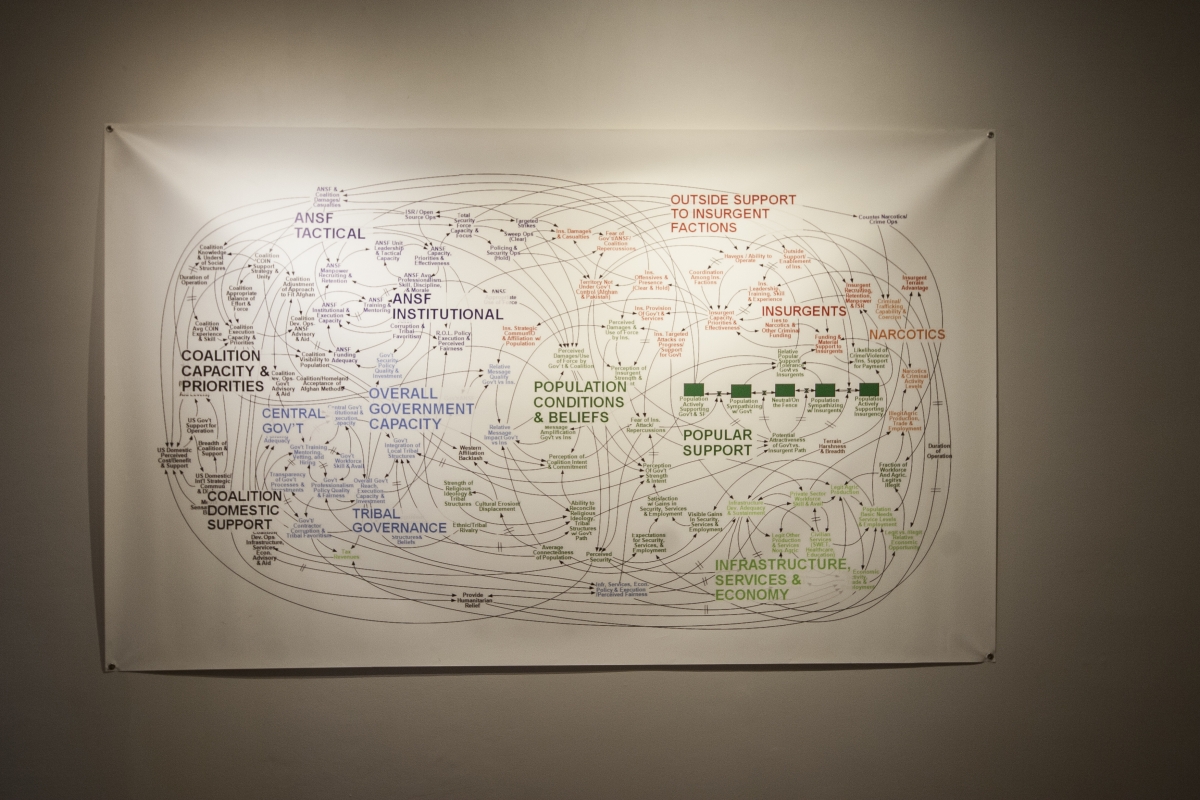

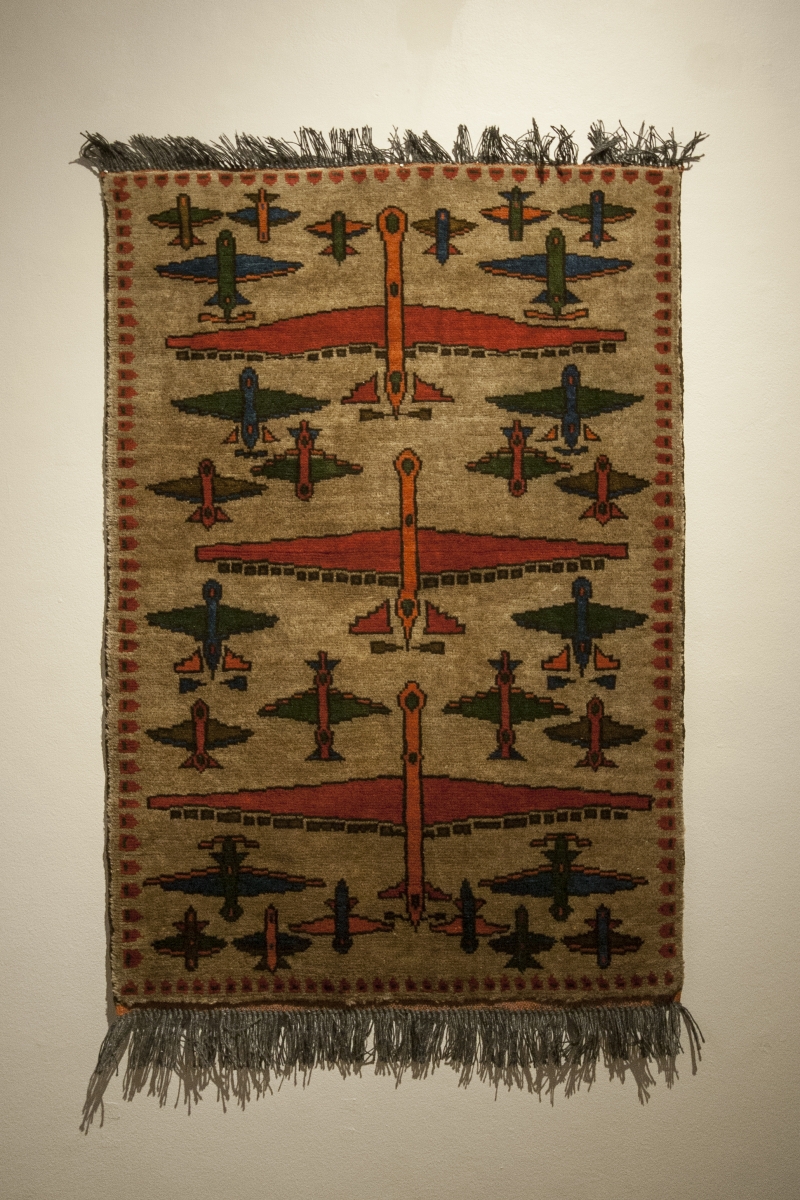

Meanwhile, the installation Pandora’s box 2.0 (2016) by Slovenian art historian and restorer Matija Plevnik is a deliberately social-political work, the catalyst of which was the aftermath of 9/11 in 2001 which turned Afghanistan into a permanent war zone. Matija’s installation, an exhibition within an exhibition, displayed several testimonies – PowerPoint presentations of strategies on how to usurp power, words that are subjected to censorship in film credits, representations of national export resources and carpets with drone motifs as the subsequent produce of war – all of which reveal the relationship between Afghanistan and Western world, as well as its consequences throughout various historical periods.

Unfortunately supply creates its own demand, which can transform local traditions or specific supplies into a global business project without any concern how it affects the country and people that are living there. This is a topic which maybe in a less pro-active way then in case of Matija Plevnik also interests Estonian artist Terje Toomistu. In her video work The Archaeology of Ayahuasca (2016) she tries to develop the story about the business of Ayahuasca brew in Amazon and experiences people have by using it. The market that is made with the help of psychedelic plants and shamanism spiritual séance provided by locals is an old story, attracting westerners since the big Geographical discoveries starting in the end of 15th century and has been affecting the so called supply countries longer than one might think. I must admit, however, that in the absence of context proffered by Rander, this documentary or more likely teaser of movie would left me indifferent, wondering what was exactly the message audience should receive besides knowledge of such kind of brew market as well as question if works in progress (as I learned to know) is always a good idea to exhibit.

Several counterpoints of this exhibition bring out the relationship between culture and power. Art, just like architecture, has always been an important instrument of the ruling power, and depending on its position, has served as an ally in its efforts to forge new systems of value. The representation of three wooden models of culture houses built in the 20th century and accompanying texts in the installation Agora (2016) by Hungarian artist Bence György Pálinkás was reminiscent of the processes of politicisation of cultural buildings.

Looking back at Matija Plevnik’s installation, he featured the painting Mutt (2016) which referenced Marcel Duchamp’s famous ‘urinal’, emphasising the imperialism of Western contemporary art and propaganda. In order to further accentuate his message, Plevnik selected ultramarine pigment for its symbolic colour. Ultramarine was highly regarded during the Renaissance period and was acquired by mixing poppy oil with lapis lazuli stone, extracted from Afghanistan’s mines during the 14th and 15th century, poppy oil also serving as a current reference to Afghanistan’s biggest export – opium.

Two pieces which coexisted as both aesthetic and social works of art in this exhibition were the sound installation Song (2015), created by Latvian artists Anna Salmane and Krišs Salmanis in collaboration with composer Kristaps Pētersons, and Foundation (I)(2016) by Jevgeni Zolotko who I previously mentioned. The work of Anna and Krišs Salmanis featured song fragments from the Latvian Song Festival, which could have been perceived as the soundtrack to the whole exhibition. Their installation developed out of a statistical analysis on the popularity of words in the repertoire of the festival’s song, revealing that besides the words ‘sun’ and ‘daughter’, ‘God’ was the third most popular word used. It was repeated almost as a mantra endlessly in the most different versions, also including Latvian anthem’s first thrilling accord ‘God’ which would usually have been followed by ‘Bless Latvia’ – as in ‘God bless Latvia’. In the context of postcolonial theory, which Rander is undoubtedly interested in, we could discuss the aggressive colonisation carried out by Christianity. However, as the Salmanis’ research illustrates, in the Baltic States pagan worship of the sun organically blended with the Christian mythology.

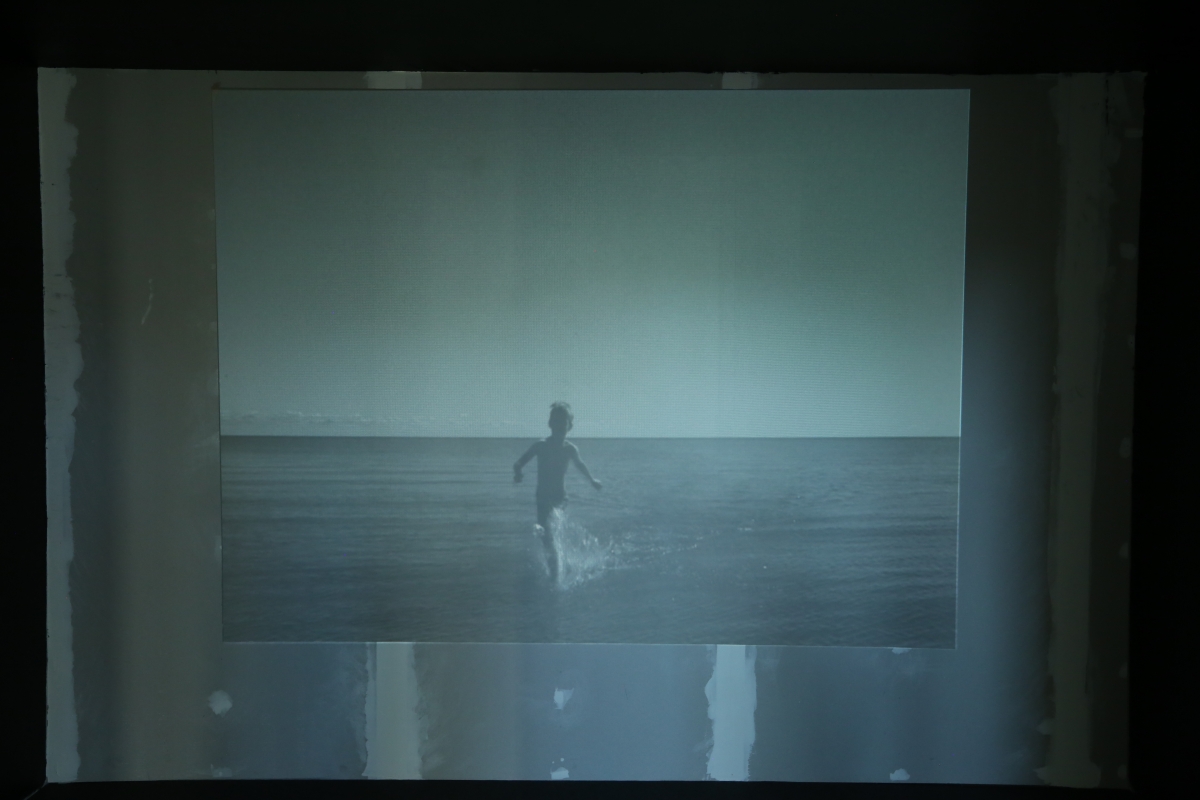

Zolotko’s relationship with Christianity becomes far more complicated with its social, cultural, historical and personal aspects merging into one. His work formed a spatial installation which utilised the gallery’s layout, transforming it into a basilica touched by entropy, its grey wooden plank wall at the far end of the room producing an instant association with iconoclasm. The space, just like father and son – the leading characters of the story line of art work, represents the eternal co-existence of such opposite categories as light and darkness, young and old, innocence and tainted by life experiences. The video installation, which resembled an altar triptych, portrayed a very private family drama as well as a few general relationship models in a rather messianic way, thus showing a rather brutal contemporary version of the relationship between God and Christ.

Rander’s project is a non-exhibition, a social-political act, where the selected works served as instruments to shine a light on a range of black spots in the system. Because the main target audience for this exhibition were the regular exhibition goers, Rander tested and questioned that part of society, which at the very least, in theory, represents its more intellectual and receptive side. Here I am reminded of the American conceptual artist Jenny Holzer, known for her powerful textual works exhibited in public spaces. One of her works from 1988 states: “IF YOU AREN’T POLITICAL YOUR PERSONAL LIFE SHOULD BE EXEMPLARY”, posing an immediate question about what ‘exemplary’ actually means. Although Rander’s project did not “illuminated” in the biblical sense one truth about the current state of humanity and did not give any solution or exemplary method to solve the existing problems in contemporary society that could be followed without objection, it undeniably triggered some issues about the Western culture and its controversial position of having metaphorically speaking the brightest light or in other words the truth of worldly order.

Galerii Noorus 13.10. – 29.10.16

Tartu Art House 20.10. – 13.11.16

Krišs Salmanis, Anna Salmane (in collaboration with Kritaps Pētersons) “Song”, Audio installation, 2015. Photo: Indrek Grigor

Rapolas Valiukevičius “Higher Education”, installation, 2016. Photo: Annika Haas

Bence György Pálinkás “Agora”, installation, 2016. Photo: Indrek Grigor

Diāna Tamane “Message: 147 of 494”, fragment of installation, 2016. Photo: Annika Haas

Matija Plevnik “Pandora’s Box 2.0”, installation, 2016. Photo: Annika Haas

Matija Plevnik “Pandora’s Box 2.0”, installation, 2016. Photo: Annika Haas

Matija Plevnik “Pandora’s Box 2.0”, installation, 2016. Photo: Annika Haas

Javgeni Zolotko “Foundation (I)”, installation, 2016. Photo: Annika Haas

Javgeni Zolotko “Foundation (I)”, installation, 2016. Photo: Annika Haas

Javgeni Zolotko “Foundation (I)”, installation, 2016. Photo: Annika Haas

Javgeni Zolotko “Foundation (I)”, installation, 2016. Photo: Annika Haas

Javgeni Zolotko “Foundation (I)”, installation, 2016. Photo: Annika Haas

Javgeni Zolotko “Foundation (I)”, installation, 2016. Photo: Annika Haas

Javgeni Zolotko “Foundation (I)”, installation, 2016. Photo: Annika Haas