Vytautas Kumža, Don’t Fall in Love With a Prop, 2018. Unfair’18, Amsterdam. Photo: Vytautas Kumža

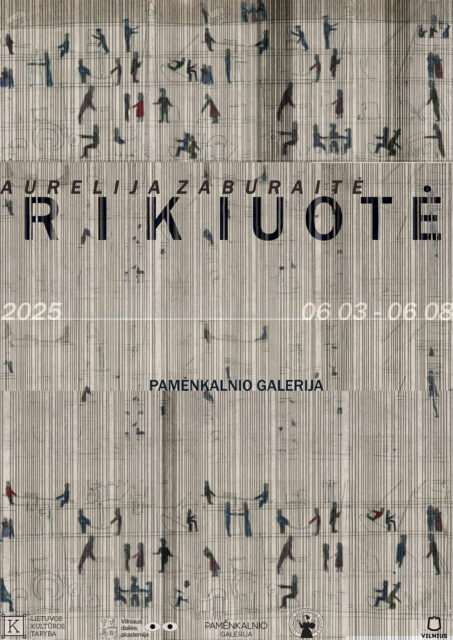

Vytautas, this time two years ago we were preparing for your exhibition ‘Trust It, Use It, Prove It’ at the [si:said] gallery. Having graduated from Vilnius College of Design and studied at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, you were studying at the time at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam. You had already received a young talent prize from the Ron Mandos gallery, and had been nominated for the European Photography and Dutch National Portrait Gallery prizes. We met in 2016, after we received funding from the city to publicly present artists originating in but living and working away from Klaipėda. You haven’t lived in this city for eight years. Do you still feel connected to it?

While I was living in the capital, I tried to avoid contact with Klaipėda. I wanted to start anew, and the cultural field there was completely different. However, I now realise and value how active my creative environment had been. KCCC and the Klaipėda department of the Association of Lithuanian Art Photographers have had a clear impact on my initial creative endeavours and on their development. However, I hadn’t had any creative connections with Klaipėda for a long time when the si:said gallery offered to exhibit my work.

How imporant is place/city/habitat in your work?

The creative atmosphere around a newly chosen place is of the utmost importance to me, starting from the cultural scene in general, to my own studio, where I work and spend quite a lot of time. It’s very important for me to be able to get inspiration there, and to give something back to the local culture too. I don’t think any specific cities are noticeable in my visual work, although I guess it influences my creative decisions.

In the exhibition ‘Trust It, Use It, Prove It’ (2016) you talk about the differences between objects and their photographic representation. How and why did you become interested in this subject?

It all started during my studies in Amsterdam at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy, while I was working at the same time as an assistant photographer. I was amazed by the difference between an object and a photograph of it, by the variability created by the light and the context. Then I started to explore the different ways in which photography can construct illusions, and also how they can be presented.

Vytautas Kumža, Tricks and Trade Secrets, 2017. Installation view, Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam. Photo: Vytautas Kumža

Your multi-layered photo-collages are usually capable of confusing even the most observant viewer. Separate details intertwine so organically that it’s difficult to put a finger on the visual axis of a piece. What should the viewer ‘read’ in your photography? Is the viewer important to you at all?

Usually, spatial sculptures or installations that exist for just a limited time only create a harmonious view from a certain point of view, until I capture it. I use many different techniques, from theatre set constructions to adaptations of analogue photography for contemporary photography. I encourage the viewer to cypher the visual implications and possible narratives. As we are now used to massive amounts of visual feeds, I set various ‘obstacles’, which show that the work was only later on made from analogue visual manipulations. The viewer is very important to me, as I am interested in how images communicate, depending on their context, and on what sense that can carry. I try to provide the viewer with an interpretive medium, and just to navigate him or her. I leave the possibility in my photographs for creating your own narratives.

In the series ‘Tricks and Trade Secrets’ (2017) you pursued the topic of trade, of the magic spell of commercialisation. What is your view of the illusionary world that photography creates?

I don’t think that I myself give in to manipulation; I’m too conscious of that aspect of photography. Images that relate to commercial photography and which allow for the banality of the genre to be grasped are my main tools for creation. The viewer sees what is familiar and readable to him, although I try to add the missing multiplicity, the general symbols and classic dichotomies. I very consciously used contemporary fashion photography, and surrealist, interwar avant-garde inspired images in the series ‘Trick and Trade Secrets’. The clearly visible iconography, interlacing narratives and images, can be read on many different levels.

Could you say a bit more about your latest photographic series ‘Don’t Fall in Love with a Prop’ (2018)?

When everything seems already written, painted and photographed, I’m more interested in techniques of visual construction than in digital image rendering or post-production. I believe we live in an era where technical myths and digital progress are no longer visible: most of the images that reach us have already been altered post-production.

I show the development of a cultural process by revealing what’s behind the scenes, and I think that’s more interesting today than the result itself. Although alterations are not usually visible in the final piece, that’s what forms the basis to my fascination for photography. I decided to show construction as a wonderful independent process, and as the potential to create photography. The series was inspired by a chapter in a beginner’s guide to photography called ‘Don’t Fall in Love with a Prop’. The publication shows how to set up a photographic studio in an amateur environment, and suggests various techniques, tips and tricks.

I created the series with that in mind, making it a visual how-to for the viewer. I use didactics, object repetition, and their functionality, as I lead the viewer through my studio space. The artwork is accompanied by a poem by Maria Barnas. The text is printed on a notepad, so that viewers can each take a page.

Vytautas Kumža, Trust it, Use it, Prove it, 2016

Recently, the emphasis has shifted towards the invisible side of the creative process. I mean both in a physical sense (behind-the-scenes tours of theatres, exhibition halls, museums) and in a mental sense (the creative process). Surely, the details of an artist’s private life, and its eventfulness, reinforce (or sometimes detract from) the intrigue. How much behind-the-scenes should be shown? Doesn’t the artist ‘bare himself’ this way? Should certain mystical moments remain private? Where can we draw the line, so that studio props don’t overshadow photography itself?

A slightly visible backstage does intrigue the viewer; it can add to a work’s effect, depending on its construction or any noticeable errors. Every artist chooses how much of his creative process, or personal life, should be revealed. By presenting his work, in a way he exposes the ideologies or topics relevant to him. That’s very individual. In my work, I only disclose the creative space, usually artificially constructed. However, the mystical moments appear by themselves, and are hard to form artificially. I believe that if a work of art has a clear concept, the studio props won’t be able to obscure the photograph.

And finally: your future plans?

I’m currently getting ready for a solo exhibition at the Villa Mondrian Museum in the Netherlands next spring. The preparation for this exhibition takes most of my time, as I try to develop new means of presenting and extending the boundaries of the photographic discipline.

Thank you for the conversation.

Vytautas Kumža, Don’t Fall in Love With a Prop, 2018, 50x70cm

Artist Vytautas Kumža

Vytautas Kumža, Tricks and Trade Secrets, 2017, 70x100cm

Vytautas Kumža, Tricks and Trade Secrets, 2017, 50x40cm

Vytautas Kumža, Tricks and Trade Secrets, 2017, 50x40cm

Vytautas Kumža, Tricks and Trade Secrets, 2017. Installation view, Galerie Ron Mandos, Amsterdam. Photo: Vytautas Kumža

Vytautas Kumža, Staged Landscape, 2017, 90x135cm