Walking on the Wall (2012) — a performative lecture on design choreography by

Julijonas Urbonas, delivered in 2012 on the façade of the National Art Gallery,

Vilnius, Lithuania.

© Ernestas Parulskis / Julijonas Urbonas

Things have the power to choreograph us, set us in motion (or into stasis). The invention of pavement, for example, had introduced the pedestrian traffic, shoes prolonged the step, while buildings had given possibility to the emergence of parkour or buildering.

In this article, I am introducing the unique creative approach of design choreography that I coined in my PhD thesis.((Julijonas Urbonas: Gravitational Aesthetics, London (Royal College of Art), forthcoming.)) The approach focuses on the choreographic power of things to affect our movements and make our bodies dance. Shifting the creative attention from conventional design goals such as usability, visual appearance, semantics, economy, ecology and safety to the conditions and effects of design choreography, I propose an alternative and dancing experience oriented design approach. Design here, in essence, is turning its attention to kinaesthetic((Proprioception, especially when connected with movement, is sometimes called kinaesthesia‘. This term also emphasises muscle memory and hand-eye coordination. Closely connected with these two systems is the vestibular system, a remarkable sensory organ near the auditory sensory complex that carries out a wide range of coordinated activities. It is connected to the eyes and ears, whose neurons respond to vestibular stimulation; it receives important input from the hands and fingers as well as the soles of the feet; it activates facial and jaw muscles; and it affects heart rates and blood pressure, muscle tone, the positioning of our limbs, respiration, and even immune responses. All of this is done to allow us to stand vertically and move through space with a rhythmic sense of balance.

See Harry Francis Mallgrave: Architect’s Brain. Neuroscience, Creativity and Architecture, New York (Wiley-Blackwell) 2010, 201.)) and whole-body-engaging dimensions of things. It encourages to move body(ies) instead of pushing image or word.

Moreover, design choreography does not deal merely with the organization of gesticulating and dangling human bodies and their parts; rather, it is concerned with the experiences these movements produce, and not only those sensual ones such as the pleasures of climbing a spiralling staircase or bouncing on a trampoline, but also the specific psychological and social circumstances the choreographies generate. As a quick example might serve Jonathan Miller’s poetic analysis of the staircase which in his words is a unique choreographic “engine, in which the moving parts happen to be the person who uses it”, but also often serves as a space allowing people “to stage their preoccupations, choreograph their politics, and dramatize their religions”.((3 Jonathan Miller: Steps and Stairs, Hartford (United Technologies Corporation) 1989, 8.))

Such examples abound, ranging from architectural to implantable scale, from entertainment to military uses, having episodic to long-term choreographic effects, etc. However, in the following text only one type of choreographic device will be reviewed: the wire, that is, various harnesses, ropes and pulleys used for suspending people. It has been chosen for several reasons. First, because such contraptions cannot be easily classified or fall into several categories at once. They are wearable, but also architectural, that is, they function only attached to an architectural body, either ready-made or specially built. Thus they lie somewhere between clothing and building. Another reason is the wide usage and spread of wire devices across different creative areas such as architecture, scenography, cinematic special effects, magic trickery design, and of course aerial dance. This allows bringing these disciplines together on the basis of commonly applicable choreographic design principles.

The strategies and methods of design choreography will be briefly and loosely introduced by analysing various versions of the wire and invoking phenomenological insights. Special attention will be given to the changing relationships with gravity, which will be considered as one of the major forces that affect bodily movement, but also and more importantly as a key element in the organization of perception. In identifying creative areas where design choreography does or might play an important and enriching role, I will provide a series of insights on how such an approach could extend the choreographic potentials of creative practices. This text does not strive to be an extensive introduction of design choreography, but to provide a fragmentary sense of the probable new discipline. Therefore, there won’t be a conclusive ending, so as to give readers some space for their own interpretation, but also to signal that this approach is just in the process of taking shape.

The text is based on my performative talk on design choreography, delivered on the façade of the National Art Gallery. This hybrid of lecture and fairground ride reconstructed the piece Walking on the Wall (1971) by famous American choreographer Trisha Brown. Unlike similar reconstructions, this re-enactment was performed not just by the author but by the audience as well – the public was given a chance to take a stroll on the wall.

The Invention of the Wire: a Non-human Choreographer

Dance historians credit the French ballet master Charles-Louis Didelot as having introduced seeming weightlessness into ballet. He might have been influenced by his performances as a boy marionette in the late eighteenth century Theatre Audinot in Paris, where sometimes puppets were exchanged for real children. Or he might just have been inspired by this imagery of his childhood. In any case, Didelot invented an adult version of the wire and harness machinery, which lifted dancers upward, allowing them to stand on their toes before leaving the ground.((Carol Lee: Ballet in Western Culture. A History of Its Origins and Evolution, London (Routledge) 2002, 189.)) The choreographer noticed and developed the lightness and ethereal quality the ‘flying machine’ gave to dance, and the audience was captivated. That is where pointe, the on-the-tip classical ballet technique, emerged. Thus it could be said that the vocabulary of ballet was designed as much as choreographed.

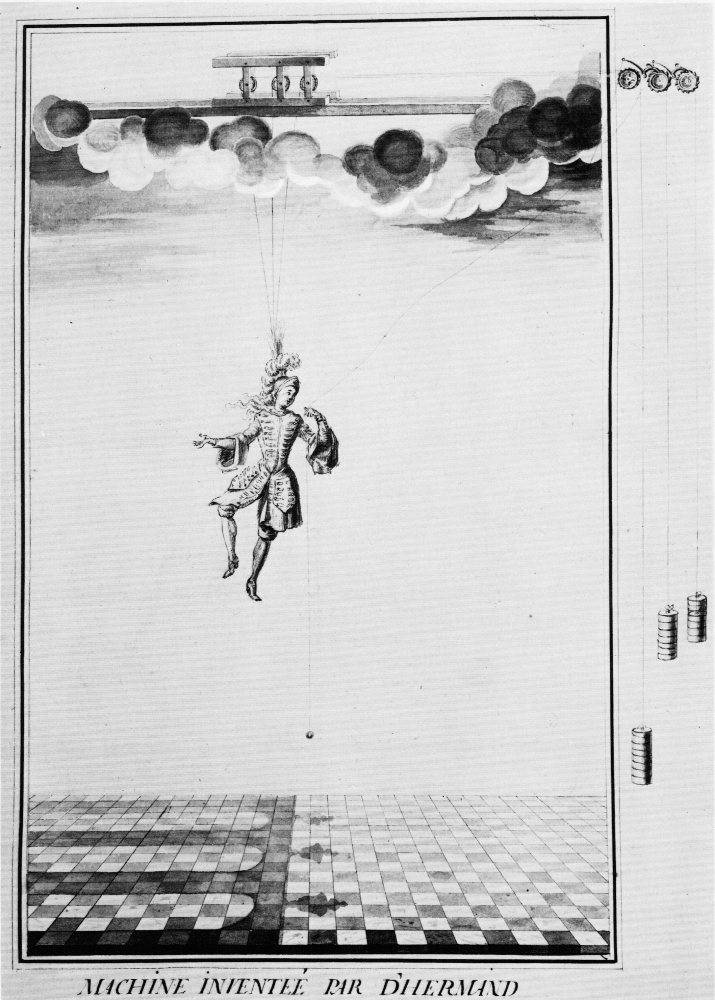

Stage ‘flying machine’, invented by d’Hermand for a ballet at the French court.

Similar device might have been used by French ballet master Charles-Louis Didelot. Engraving, late 17th century.

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

Changing Relationship with Gravity: Altered Perception

Between 1968 and 1972, the American dancer and choreographer Trisha Brown – an aerial dance pioneer – had been using various custom made harness devices as well as ready-made mountain climbing equipment for her performance series Equipment Dances which studied choreographic transformations of the body’s relationship to gravity. Brown focused on ordinary movements like standing, walking or dressing up to demonstrate how they were intrinsically governed by earthly downward pull. One of her first performance pieces, Floor of the Forest (1970), was about getting dressed horizontally. It was as much about dancing as it was the effects of a choreographic prop: a 4 by 5 meter frame made from pipes with ropes tied across. Unto these lines clothes had been hung tightly together with sleeves attached beneath pant legs, forming a solid rectangular surface. The audience was free to move around the periphery of this wearable architecture as the performers dressed and undressed their way through the structure. Watching a video documentation of the performance, it is hard to not take notice of the dramatized power of gravity – even well trained dancers struggle with the quotidian and normally vertical activity.

Floor of the Forest (1970), a choreographic installation by Trisha Brown. Performed by dancers from Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance, at the Southbank Centre, London, 2010.

© John Mallison / Trisha Brown Dance Company

Floor of the Forest (1970), a choreographic installation by Trisha Brown.

© Agathe Pouponey / Trisha Brown Dance Company

Other dance pieces involved dancers performing on surfaces perpendicular to the ground. In Man Walking Down the Side of a Building, Trisha Brown sent her dancer down the façade from the rooftop of her SoHo loft, a seven-storey building. The dancer, strapped into a mountaineering harness, simply walked down the side of the building with arms held tightly to the sides of his body. The quotidian pedestrian activity turned perpendicular is no longer recognizable, challenging body knowledge in such a way that even the well trained choreographer Elizabeth Streb walked like Frankenstein’s monster, as she struggled to keep herself fully upright and her arms – that must have felt very heavy – on her side while moving forward and downward during a historical recreation of the piece.((Gia Kourlas: Elizabeth Streb. In: Timeout [online], 12/5/2011. Available: www.timeout.com/newyork/art /elizabeth-streb?pageNumber=2, last accessed 11/20/2012.))

Man Walking Down the Side of a Building (1970), a performance by Trisha Brown, reperformed on the wall of the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 2008.

© Pepe Barbe / Trisha Brown Dance Company

In Brown’s Walking on the Wall, which was performed at the Whitney Museum of Art, harnessed dancers were perpendicularly hung and could walk, run or remain still at varying heights on two right-angled walls with the aid of climbing ropes and extended tracks that curved around the room.((Chris Salter: Entangled. Technology and the Transformation of Performance, Cambridge, Mass. (MIT Press) 2010, 245)) The performers were walking ‘horizontally’ as if they were taking a casual stroll in the street, stepping around corners, meeting and parting and never looking down, where the spectators were actually situated. But which way is down?

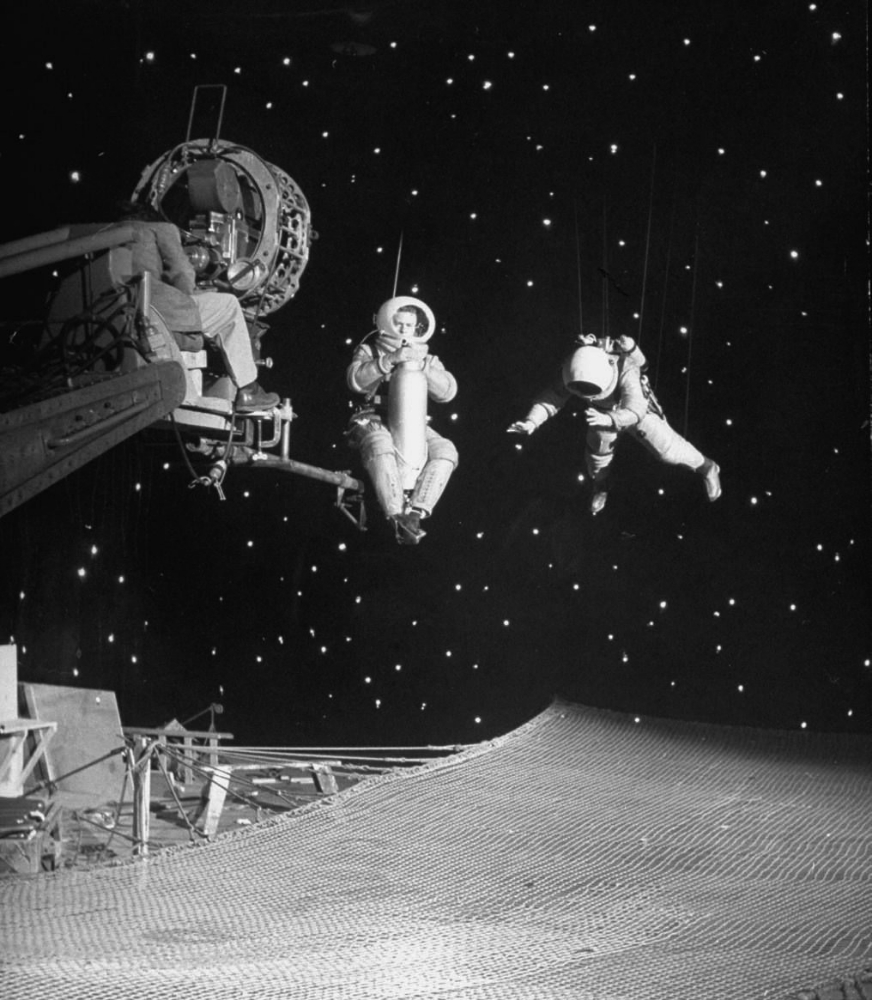

Much like in a weightless atmosphere, it is up to the spectator to decide. The only difference is that this question is posed not up there, in outer space, but down here where gravity pulls us incessantly and irresistibly. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that almost an identical performance had been staged a decade earlier by NASA in preparation of the Apollo 11 mission with a device called Reduced Gravity Walking Simulator. This was also based on ropes and harnesses, used to evaluate the effects of lunar gravity (one-sixth of that of the Earth) on man’s walking and running capabilities. An astronaut weighing 80 kilograms perpendicularly hung against an almost right-angled wall and ‘standing’ on it would have exerted a force of only 15 kilograms – the same as if he was standing upright on the lunar surface.((Francis Smith: Simulators For Manned Space Research. In: Spaceflight Revolution, NASA SP-4308, March 21–25, IEEE International Convention, New York (NASA) 1966.))

A test subject being suited up for studies on the Reduced Gravity Walking Simulator located in the hanger at NASA’s Langley Research Center, 1967.

© NASA / Langley Research Center (NASA-LaRC).

These examples are unique yet limited to professionals and specific audiences. It might seem that only performers could actively immerse themselves in the wire-enabled new sensual realms, but in fact even spectators’ eyeballs could be set into dancing motion. This is the creative domain where empathy manifests itself at its best. And it could be choreographed by design.

The Empathy: Conjuring Dances

In their practice, Trisha Brown as well as other aerial dancers has not been disguising the means of suspension, because their creative attention has been devoted to the bodily movements the devices allowed, not the hardware itself.However, the display of the equipment is a part of the spectacle hard to ignore. The performers experience severe tension in their muscles, pressure of the harnesses and spatial reorientation, whereas the spectators are left to imagine such experiences by empathizing with the performers. The latter may try to disguise their effort, yet the tension of the ropes provides a hint on what is it like to challenge gravity, what is it like to become such a wire-led being. Such an effect has been creatively employed by choreographer Elizabeth Streb for her gravity-defying-or-defining dance performances that fuse extreme sports, modern dance, stunt work, acrobatics and circus. An important element of her dance work is machinery, which provides the possibility to explore “what it could do for the body that the body could not do for itself ”,((Michael Homes: Interview with Elizabeth Streb. In: Bomb Magazine [online], 7/2010. Available: www.bombsite.com/issues/112/articles/3525, last accessed 5/25/2012.)) but also strengthens the sensual connection with the audience. Streb likes to amplify the physical aspects of her pieces – such as the thuds of her performer’s high landings and the clank and clatter of the stage equipment – either mechanically or audio electronically.((Nancy Reynolds/Malcolm McCormick: No Fixed Points. Dance in the Twentieth Century, New Haven (Yale University Press) 2003, 625.))

This approach is employed differently in cinema, particularly when it comes to special effects. Cinema is a lot about visual trickery and illusionism, and therefore it does not usually expose the methods behind the tricks such as the wire systems of the superman flight or the technical means of producing rotating gravity effects to the audience (recall the famous jogging scene under artificial gravity in the spaceship Discovery of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey). Since the suspending devices discussed previously create certain conditions that emulate weightlessness, they have also been used for numerous scenes in films from supernatural fights to sex in outer space. For example, Fritz Lang’s silent movie Woman in the Moon (1929) demonstrated for the first time on screen the absence of weight in space three decades before anyone experienced it for real, that is, before the invention of the reduced gravity aircraft, aka “vomit comet.”((Mark Brake/Neil Hook: Different Engines. How Science Drives Fiction and Fiction Drives Science, London (Palgrave Macmillan) 2008, 81.)) In the rocket on its way to the moon, the passengers have to hold handrails and put their feet in special belt nooses attached on the floor to prevent themselves from floating away, much like it is done by astronauts today. In one scene, most likely employing rig and ropes, a boy performs a light jump to find that it would thrust him so high that only the ceiling of the rocket would stop him. Despite the lack of the motion fluidity, the encounter should have compellingly introduced the new realm of bodily motions in space, but also inspired future filmmakers such as George Pal in whose movie Destination Moon (1950) a rocket’s crew also experience weightlessness and use magnetic boots to attach themselves to the spacecraft’s floor and walls. More recently, the movie Inception (2010), directed by Christopher Nolan, depicted unique scenes of altered states of gravity, where gravity’s direction tilts or even spins around, and one of the proponents careens down hallways that shift and turn upside down. In another scene he fights an array of armed men in zero gravity rooms, bouncing off walls and ceilings like a martial-artist-cum-astronaut. One zero gravity sequence shows the character taking five weightless sleeping bodies, wrapping a chord around them, and floating them down the hall into an elevator. The scenes are noticeable for their extraterrestrial choreographic verisimilitude that was enabled by a unique combination of techniques, most of which were custom designed, such as wire structures and rigid poles like big popsicle sticks for suspending actors midair, even custom moulded fibreglass supports built to fit their bodies. Such trickery is of course concealed to amplify the plausibility of the choreographic circumstances the contraptions allow to simulate, but also to enhance the cinema’s empathetic link with the spectator.

Behind the scenes of the movie, Destination Moon, USA 1950, 92 min, George Pal Productions, directed by Irving Pichel.

© Allan Grant / Time Life Pictures / George Pal Productions

The concealment of the trickery is even more important in stage magic and conjuring arts. More than cinematic special effects, magic tricks demand that the device itself is designed to make it hardly visible (or rather invisible). In cinema harnesses could be masked with the help of computer graphics or photomontage, whereas magic wire-based contrivances have to be created in such a way as to be undetectable to the human eye. This is usually achieved by hiding a harness beneath a costume and using very thin wires, and then enhancing the masking effects with special lighting. In addition to that, since the important part of magic tricks is mystery and wonder, trickery not only has to be undetectable but also should be immune to certain challenges and give ‘testimony’ to the absence of trickery. For example, passing a hula hoop around the body of the levitating performer ‘proves’ the authenticity of the magic or at least dramatizes wonder.

![Flying Illusion (1992), a conjuring performance by David Copperfield. A snapshot from a video recording from: David Copperfield - Illusion. 2004 [DVD] California: Standing Room Only. © David Copperfield / Standing Room Only](http://www.echogonewrong.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/David-Coperfield-levitating.png)

Flying Illusion (1992), a conjuring performance by David Copperfield. A snapshot

from a video recording from: David Copperfield – Illusion. 2004 [DVD] California:

Standing Room Only.

© David Copperfield / Standing Room Only

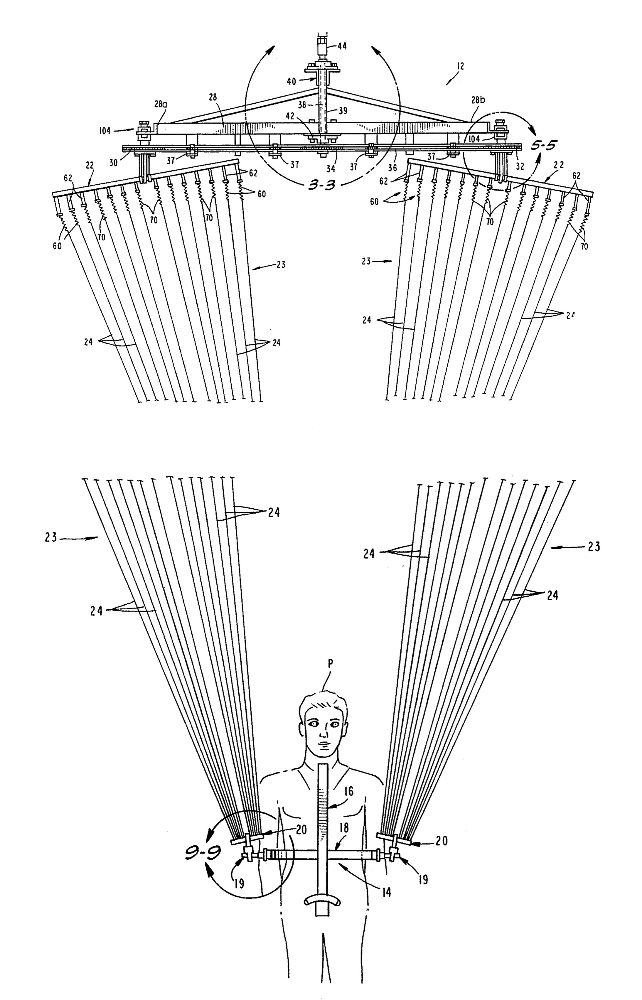

Levitation Apparatus (1994) — a fragment from a patent of a conjuring device by

John Gaughan, U.S. Pat. 5,354,238.

© John Gaughan

Performativity and Thingly Agency

Copperfield’s equipment is unique indeed, and his dance is relatively graceful. The device’s choreographic potentials, however, are yet to be explored. Copperfield is not much interested in this as he makes do with imitating movements such as those of swimming underwater. His levitation dance hardly goes beyond the level of just saying: “You see, I am not using any ropes”. It does not invite aesthetic appreciation and interpretation but rather wonder about what makes him levitate. Unfortunately, the same issue applies to all magic levitation performances I have seen so far. The magicians David Blaine and Peter Marvey, also well known for their magic levitation performances, included. I cannot help but wonder what contemporary aerial dancers such as Trisha Brown or Elizabeth Streb would make of such devices as Gaughan’s computer controlled wire machine.

Actually, among the choreographic machinery the STREB dance company uses – such as pneumatic human launching devices, a human-sized yo-yo and customized bungee structures –, there is a rotating harness very similar to Copperfield’s.

Waterfall, a dance performance by Elizabeth Streb at Millennium Bridge in front of

Tate Modern. Streb’s dancers performed acrobatic extreme-action aerial dance

routines at seven surprises across central London as part of “one extraordinary day”. Choreographed by Elizabeth Streb. Part of the London 2012 cultural Olympiad. Sunday 15 July 2012.

© Michael Jones / Elizabeth Streb

Designed by the Professor Hugh Herr, the head of the Biomechatronics Lab at MIT, the harness was originally created for the show Brave (2009), during which performers executed aerial cartwheels and flipped off a vertical wall, frontally and sidewise, with occasional inverted free-falls stopping a foot before heads would have met the stage.((Tiffany Chu: STREB Dancers Are Brave, Indeed. In: The Tech, vol. 129, no. 51, 2009, 9.)) The device later featured in Speed Angels during the Cultural Olympia in front of the National Theatre as part of the 2012 London Olympics. In the performance, three transcendent bodies were attached to high-speed winches that rocketed up and down at various velocities, sometimes reaching the dizzying speed of eight meters per second. The speed made the dancers virtually disappear from their various spots in space as they mimed, in ever more intricate ways, body rising and falling from 30 meters above the earth to skimming the ground’s surface. At that height and at that speed, the suspendees assumed extraordinary shapes and forms, turning where it seemed impossible, holding shape, ascending and descending together and apart to create muscular arcs in the air.

Speed Angels, a dance performance by Elizabeth Streb at the National Theatre.

Streb’s dancers performed acrobatic extreme-action aerial dance routines at seven surprises across central London as part of “one extraordinary day”. Part of the London 2012 cultural Olympiad. Sunday 15 July 2012

© Michael Jones / Elizabeth Streb

Having explored a hardware-derived choreographic performativity, and engineering such machinery by herself, Elizabeth Streb notices that the inventions not only enable new movements and orientations of the body, but also co-choreograph the dances on their own: “Even though I think I know what might happen with them [choreographic contraptions] once I get them in the space, never the twain shall meet. What I think I know about movement is constantly defied by what the machinery and the dancers reveal to me in practice and by the reality of space, time, and forces.”((Michael Homes, Interview with Elizabetz Streb.))

This is nothing new or radical – creative people often find themselves being ‘steered’ by the things they develop. However, what could be unique is pushing such a material agency to its extreme, that is, designing an object with some sort of choreographic performativity and only then create choreography to specific purposes or formats such as stage dance, cinema or circus. A design choreographer designs a machine, which is later explored by a choreographer or dancer, or actor, or pedestrian, then by a creative director. Finally, an art piece – a dance composition or a theatrical performance or a film script – is conceived during such a free and loose submission to an object’s implicit choreographic didactics and performative capacity. This experimental and open-ended approach may be difficult to direct and its outcome would be unpredictable, but such precedents as Charles-Louis Didelot’s flying machine should encourage us to take up that challenge.

Julijonas Urbonas (Vilnius/London) is a designer, artist, writer, engineer and PhD student in Design Interactions at the Royal College of Art. Since childhood, he has been working within the field of amusement park development. Having worked in such field – as an architect, ride designer, head of fairground – he became fascinated by what he’s calling ‘gravitational aesthetics’. Since then the topic has been at the core of his creative practice, from artistic work to scholarly articles. His work has been exhibited internationally and received many awards, including the Award of Distinction in Interactive Art, Prix Ars Electronica 2010. One of his projects can be found in the permanent collection of the Centre for Art and Media Karlsruhe (ZKM).

The original article is published in: Dennis Paul & Andrea Sick (Eds.): Rauchwolken und Luftschloesser, Hamburg (Textem-Verlag), 2013, 117-127.