‘Introduction to Posthuman Aesthetics’ installation, NKNU Art Centre, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2017. Photo: Christian Döller

I met Mindaugas Gapševičius (miga) and joined the Migrating Art Academies project that he initiated in 2013, followed by many further projects with Institutio Media. We have been communicating by email since then, using this abstracted and reduced means for our collaboration. In generating and developing ideas and concepts, as well as coordinating processes collectively, we have never had enough time to discuss all those even more important questions, such as our future as a species, competition between new forms of life, and the interaction of art, science and education.

Lina Rukevičiūtė: Miga, you keep searching for the secrets of life. Scientist are still only talking about some animals which have the secrets hidden in their organisms but are not yet decoded (such as turtles, lobsters, and some types of worms and jellyfish, whose bodies are resistant to ageing). At the same time, technological progress is focused on artificial bodies, human or animal, which are expected to live for ever as soon as they are created. How long do you think this might take?

Mindaugas Gapševičius: If I was honest, I would not try to answer this question, because nobody knows the answer. However, we can try to guess or predict future events. Some transhumanists say that it will take about twenty more years before the consciousness is transferred to a computer. Biochemists, though, estimate the same length of time for discovering the genetic code related to ageing, which could be adapted by other organisms. As for myself as an artist, it’s more interesting to ask other kinds of questions: how will these new forms of life coexist with other forms of life, and what challenges will they face? We should be looking for various visions of the future now. I think the task of any contemporary artist is to raise similar questions.

L.R. We could say that evolution is going in two main directions at the moment. Machines and artificial intelligence are being developed to the level of human intelligence, and are aiming to overtake it. At the same time, the position of humans in the system of live organisms is being questioned, biological processes are being interfered with, the origins of human life, and man’s general purpose and his relationship with other live organisms are being discussed. Do you think these two directions are parallel?

M.G. Thank you for summarising everything that is currently going on in theoretical, technological and artistic discourses. I should not be too categorical in saying whether these two developments are parallel. On one hand, if we follow the transhumanist world-view (Marvin Minsky, Ray Kurzweil), we could say that we are moving towards superhumanity, with the aim of subverting the entire ecosystem. On the other hand, if we draw on traditional post-humanist theory (Donna Haraway, Rosi Braidotti), we will see a clear attempt to understand the world around us, and count ourselves among coexisting organisms (animals, plants, microorganisms). Still, I would say that everything is interconnected, and that one direction is inseparable from another: if we can transfer our consciousness to a computer, it would not necessarily imply the enslavement of other forms of life. The question should be put somewhat differently: for example, will we manage to save ourselves and our own ecosystem while fighting and quarrelling with each other? Or how not to circumvent evolution? I wonder what you think of this question yourself.

‘Introduction to Posthuman Aesthetics’. ‘Mycorrhizal networks or how I hack plant conversations’ toolkit, 2016-2017. Photo: Christian Döller

L.R. I’m more interested in asking whether it’s beneficial for us at all to circumvent evolution. For the sake of a happy end scenario, I would expect members of the first movement not to decrypt this code.

M.G. Well, it’s not exactly clear what this happy-ending scenario is. At the moment, we’re struggling to imagine living on a purely virtual level. However, in the future, this might be the only happy ending. Perhaps everything depends on how we construct our own understanding of the world.

L.R. I understand you still admit that a difference between these two directions exists on a philosophical level. So I would like to ask you about ‘self-repair’ laboratories: what aspirations shaped their concept? Is ‘self-repair’ about circumventing technological evolution, or is it about escaping self-destruction? What motivates you? Or is there something that scares you?

M.G. I have set my goals on knowledge where both theoretical and practical problem understanding and solving methods are equally important. Let’s try to look at how humanity functions in a capitalist environment, where everything is defined through the prism of the product: not only is the product what we create, the product also creates us. I mean the pharmaceutical industry or computer technology, for example, through which our consciousness and understanding of the world are constructed with the help of others. The ‘self-repair laboratory’ was developed by reconsidering the structure of the world. In this laboratory, we ask questions about self-organisation, and look for answers. The laboratory provides participants with an opportunity to exchange knowledge with colleagues, and to find some new skills, such as how to analyse gene mutations at home. Even more complex projects can be developed, such as finding out the features of a cloned baby, for in the future we will be ‘making’ babies in vitro!

In my opinion, having at least a basic technological and scientific knowledge allows us to handle life’s situations more wisely, and to make better decisions for ourselves and our environment. ‘Self-repair lab’ to me is a medium through which we can create fantasies, and look for answers to some of the most important questions.

L.R. What does ‘self-repair’ actually mean, what kind of concept does it relate to? Could you give some examples of how the results from such laboratories could affect our environment?

M.G. ‘Self-repair’ is linked to historical concepts, such as self-organisation, self-reference and autopoiesis. To put it simply, ‘self-repair’ relates strongly to the adaptability to live in a changing environment: when we talk about evolution, we say that life has survived due to its ability to adapt to changing conditions (for example, Lynn Margulis’ theory of evolution). With the aim of ‘self-repair’ being to adapt to present conditions, we need to reflect on developing technologies, scientific discoveries, the changing understanding of ourselves as beings. So if we drink kombucha tea together with participants in creative workshops, we realise that we are helping our body’s immune system this way. And if we share our thoughts about the ability to store data in the same bacteria that we drink, we understand that in this way we will help the ecosystem, since we are not using electronic devices to store data.

L.R. How do you see your artistic practice in the context of these creative laboratories?

M.G. In art world terminology, ‘laboratory context’ would be ‘performance’, and ‘toolkits’ would be ‘installation’. The only difference is that during the performance, we isolate ourselves from the audience as artists, and in creative laboratories we are together with the audience: we create, interact, analyse and dream. In addition, we take and use toolkits, while elements of art installations can’t be touched, because we might dirty them or damage them in some other way. Looking further, the context of laboratories could be approached through Nicolas Bourriaud’s 1990s term relational aesthetics, where the role of art is described as ways of living (1). Toolkits could be contextualised via Matt Ratto’s term critical making, describing the meaning of the making process, or Levi-Strauss’ term bricolage, which describes people engaged in activities between art and engineering.

Any attempt to distinguish artistic and non-artistic practices, or artists from non-artists, is a kind of discrimination. In my opinion, communication and communicative content are more important: the transfer of thoughts, ideas and knowledge to others. In my creative practice, communication, ideas and experience are all intertwined, and they keep changing in real time, so probably what I’m currently living with could be called my artistic practice. If we have a self-repair lab, then it means it’s part of my artistic practice.

L.R. Could you say what it was that led to the fundamental change in your practice: from analysing artificial networks to an interest in natural biological processes, which in a way are also networks?

M.G. I remember the Migrating Art Academies laboratory ‘Food–Biotechnologies–Neocolonialism’, during which I was interested in dead crystals, which, when formed, resemble living organisms. So this event could be the turning point, when my interest in biological processes gained momentum, and led to a series of new works. Still, I think my interest in computer networks has not gone, just there was a need for other kinds of knowledge in this Migrating Art Academies event. At that time, I realised that artificial intelligence without biological processes was limited, and that a knowledge of biology and an understanding of biotechnology were necessary to go further. Looking at some emerging issues from different angles allowed for a deeper understanding and a rethinking of current phenomena. In this way, my interest has shifted from computer networks to networks of people, tools, knowledge and experiments.

L.R. Will those who realise their advantage over machines and algorithms survive in the unpredictable future? What are qualities such as creativity and contingency worth? Can any knowledge obtained via self-repair laboratories help?

M.G. I think we need to cooperate and learn to live with machines. If we try to deceive them, they’ll try to deceive us as well. We’ll only win if we manage to accept their advantages, and offer them our own advantages. Twenty-first-century creativity has shifted compared with the twentieth-century concept of creativity. For example, Wikipedia states that creativity is the act of creating something new and useful. Creativity comes from experience, from asking new questions, and looking for answers. If, for example, the machine has a lot of experience and a lot of answers on the basis of the information it has obtained, asking new questions is more difficult. Of course, we can teach them to ask new questions, but what use would that be to machines? It’s not possible, however, just to install creativity in machines. The only way it might work would be if human consciousness was downloaded on to a computer. As of contingency, it is much easier to reach it by just selecting a random function in machines. I remember a good old internet project ‘Postmodernism Generator’. Do you remember that? The machine can ask questions and give intelligent answers. However, only observers can see the meaning of such action.

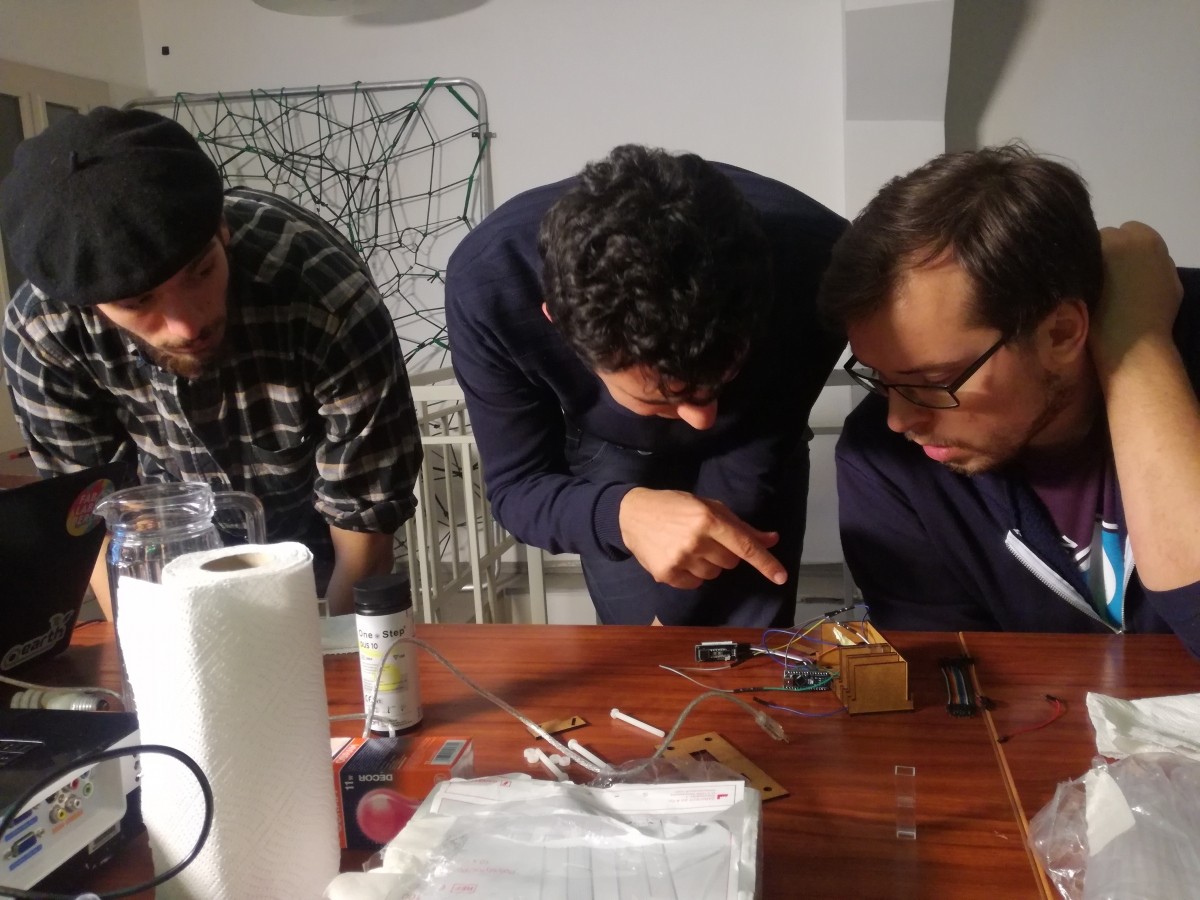

‘Introduction to Posthuman Aesthetics’ workshop, HGB Gallery, Leipzig, 2017. Photo: Fabian Bechtle

‘Self-Repair Laboratory’, Sodų 4, Vilnius, 2017. Photo: Brigita Kazlauskaitė

L.R. I agree, but not with the part about contingency. This is a unique feature, which allows humans and the entire living environment to be unpredictable in their development, and not just follow a random sequence of previous processes, actions or thoughts. It allows us to escape from predictable simulated reality, and to remain ‘non-readable’. It is this frightening, and at the same time joyful, contingency which the writer Douglas Adams talks about in his books. Therefore, I think this feature is related more to creativity and intuition-based creative practice. Contingency is also related to an ability to connect objects, actions and processes which it would not normally be possible to connect into new unexpected processes and combinations. Contingency is used to fight simulation. I wonder if artificial intelligence will master this trait …

M.G. All right, I can see you mean another kind of unpredictability. But where does intuition come from? Is it not from experience? Let’s have a look at the Google search engine: once you start typing a word, the machine starts suggesting possible searches. This is not necessarily a bad thing, as the machine is helping you to make up your mind, to decide what you are really looking for. On the other hand, every person is able to predict his own actions, based on earlier experiences. This is the intuition you referred to earlier. Of course, it is much more difficult to foresee the actions of others, since the experiences of others are unknown. But if we aim to store as many experiences as possible outside our inner selves, and if these experiences are made available for others to use, unpredictability may no longer exist.

L.R. In the climax of the development of machine and algorithm, what do you think about their ability to merge with living organisms?

M.G. Well, a merger is no secret at all: chemical signals can be converted into electronic impulses and sent to a computer. Or vice versa: chemical signals can be activated by electronic impulses. A prosthesis can be controlled by human thought. Electronic impulses can be sent to the brain to influence their work. However, human consciousness has not yet been transferred to a computer, and it has not yet been reinstalled from a computer back to a physical brain. Still, I would ask the question in a slightly different way: how would computers influence creative processes? What kinds of questions will we ask after we ‘consult’ with databases in real time?

L.R. Perhaps it is worth mentioning the machine wilderness (machinewilderness.net) project of augmented ecology here, which is influenced by creative processes. It aims to find creative solutions for the changing natural environment. It’s true, though, that this process is still going on with human intervention.

M.G. Yes, it’s a good example. Imagine that you need some kind of ‘health report’ from an organism. You touch it, diagnose its illness, and cure it. If we are speaking about creative processes, we can imagine sharing experiences among different organisms, posing relevant questions, and looking for answers. The fact that what I’m talking about now is no longer from some fantasy series. Scanning another organism’s DNA and identifying gene mutations in home conditions has become a reality.

L.R. May I ask you the same question you asked one of your colleagues in a recent interview: for as long as I know you, you have been studying all the time, right? Where have you taken yourself to during this time?

M.G. This is a funny reference to my conversation with Julius von Bismarck, thank you. I have been studying, with breaks. After graduating in painting from Vilnius Academy of Arts, I had a ten-year break, after which I enrolled for a PhD in London. I’m currently doing a PhD in Weimar. These are studies which result in some kind of qualification. However, there may be other kinds of studies, such as when you organise an environment for the exchange of knowledge yourself. I mean the project Migrating Art Academies that we’ve been working on together for the last few years. It’s amazing when you can share your insights with colleagues, ask questions and search for answers together.

L.R. The longer you live outside Lithuania, the more you implement your creative ideas in Lithuania and get involved in its artistic context. Is this something you aimed for initially, or did this artistic context and its curators draw you in?

M.G. I never intended to be an émigré, and I have always associated my activities with an international context. Even Migrating Art Academies was designed for students at Vilnius Academy of Arts first of all. I think my Lithuanian experience is important to me here in Germany. And the other way around: my experience from Germany is very useful when acting in the Lithuanian context. I don’t see the point in ignoring the fact that my experience is diverse.

‘Self-Repair Laboratory’, Autarkia, Vilnius 2017. Photo: Brigita Kasperaitė

L.R. Why is it so important to you that everything, from the development of discourses to the tools, methods and outcomes in artistic processes, is accessible to absolutely everyone and in an everyday environment?

M.G. To me, it just seems very important. Let’s take, for example, speculative design: we can follow the latest news in science, and imagine it implemented in practice in the future. We can imagine a piece of meat grown in a laboratory, or an illuminated avenue of trees. It’s easy, right? And now, imagine how an electronic signal changes our thinking: that’s more difficult to imagine. Undoubtedly, scientific inventions are interesting, and we follow them in order to create new interpretations of our surroundings, with innovations adapted to our daily lives. Still, not knowing how, for example, to grow our own damaged skin tissue, we can feel a bit limited. I don’t mean that we need to know everything, but just getting to know new things in the daily context is very important. Then we’re not only observers, but also participants. When we become a part of the process, and once we understand how the processes work, we can influence the processes ourselves. Then we start to understand the world in a different way, other than from scientific news. On the other hand, I’ve already mentioned that we create products, and products create us. So by having an opportunity to understand and verify how life-changing processes work, we become less dependent on others.

Mindaugas Gapševičius (b. 1974) is an artist, facilitator and curator, based in Berlin and Vilnius. He obtained his MA at Vilnius Academy of Arts in 1999, and his MPhil at Goldsmiths, University of London in 2016. Since 2016, he has been conducting PhD research at Bauhaus University, Weimar, where he holds an artistic associate chair.

Gapševičius was an active participant in international new media art networks which stimulated the formation of networks between Western countries and the Baltic States in the last decade of the 20th century. He is one of the initiators of Institutio Media, the first Lithuanian new media art platform on the internet, founded in 1998, the Migrating Art Academies pan-European network for emerging artists, founded in 2008, and the BioMedia network of Nordic and Baltic countries, founded in 2017. In 2017, he set up the first community-based biolaboratory in Berlin, together with colleagues from the TOP Association. His works question the creativity of machines, and do not presume humans are the only creative force. Gapševičius’ work has been shown at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius (2002), the National Centre for Contemporary Arts in Moscow (2004), Berlin Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien (2006), Rencontres Internationales Paris/Berlin/Madrid in Paris and Madrid (2008), KUMU museum Tallinn (2011), Pixxelpoint festival Nova Gorica (2014), Pixelache festival Helsinki (2015, 2016), and RIXC art and science festival, Riga (2016). http://www.triple-double-u.com

“0.30402944246776265” Malonioji 6. vilnius, 2014. Photo: Evelina Kerpaitė

(1) Bourriaud, Nicolas. Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2002. pp. 13, 113. Translated from Bourriaud, Nicolas. Esthétique relationnelle, 1998.