My Name is 192.168.159.16 (2009). Courtesy: Varvara& Mar

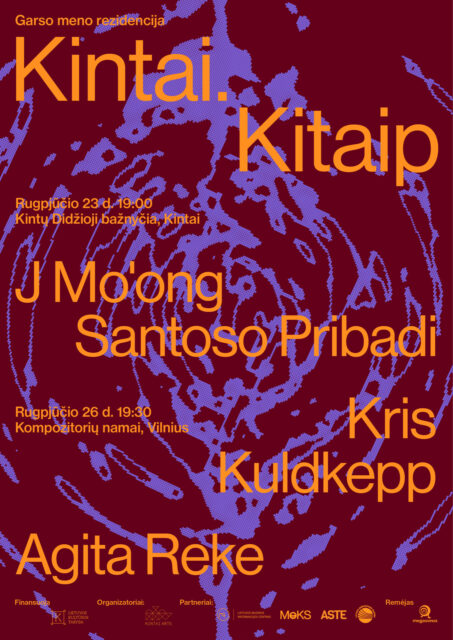

Varvara Guljajeva & Mar Canet, whose artistic projects involve technology, data sculpting and audience interaction, have been working together as an artist duo since 2009. Estonian-born Varvara and Barcelona-born Mar currently live and work in Tallinn and have exhibited their art pieces in a number of international exhibitions and festivals. In 2014, the duo were commissioned by Google and the Barbican Centre to create a new art piece entitled Wishing Wall for the Barbican’s immersive Digital Revolution exhibition. Last year Varvara’s & Mar’s public art proposal for Green Square Library and Plaza in Sydney was nominated for the second and final stage.

Merle Luhaäär: It’s funny, when I think of artistic duos, trios, collectives and whatnot, I always think of them as being one whole bias-like structure that excludes everything individual, rather than consisting of different people who are (temporarily) united by similar ideology. What I am saying is that there is this phenomenon of losing one’s individuality by becoming a part of something else, something bigger. Likewise, with the London-based artist duo Gilbert and George, who decline to discuss their previous lives, there is no Gilbert without George or George without Gilbert. There’s just one ‘dragon’ wearing flamboyant tweed suit with two heads. You have been known as a duo for quite a long time now – since 2009. Could you tell me how did you come to identify yourselves as the artist duo ‘Varvara & Mar’? Do you feel it is more like a temporary (albeit a long-term) symbiosis or will it define your whole existence as artists, and do you think it’s easier to ‘get away with the art’ as a duo rather than being ‘lonely wolves’?

Varvara Guljajeva: I often wonder from time to time if there is Varvara without Mar and Mar without Varvara. It is probably quite unlikely. We started to work together quite naturally and very gradually. To clarify, we first became a couple a year before we discovered we could also work together. As young artists, we were spending all of our free time in the studio making art and talking about it. When we realised that getting feedback from each other with our ideas was pretty good, we began collaborating together on our first project in 2009 which was entitled My Name is 192.168.159.16 (2009), which received an award when it first exhibited. It won the 23rd Stuttgarter Filmwinter media installation prize. A year later, we created another two works together which were also quite strong, and since 2011, we have signed our work together as Varvara & Mar. The main reason for that was to begin our non-stop residency tour together. We then spent three years doing artist residencies together; 13 in total in 11 different countries, if I am right.

Mar Canet: To be honest, the kind of work we do is impossible to realise as lonely wolves, unless we could individually pay for well-skilled crews to work for each of us. You might have noticed our works talk in a digital language, but most of them are physical installations that are interactive and/or kinetic. When it comes to production, we are both hardworking. I am good in certain things and Varvara is great in others. There have been numerous additional administrative and maintenance tasks which continue to need ever more attention. I really don’t imagine being able to do it all by myself. I also enjoy brainstorming and developing artistic concepts together.

ML: You’ve previously mentioned that you don’t like classifications of art based on medium and that you think of the term ‘new media’ as being inappropriate to describe your art. The things that seemed new this morning are probably old by tomorrow or even this afternoon. Still, I have to admit that when I started to think about your art I felt the obvious wish to classify it, to place it somewhere in particular – as we all have a tendency to classify objects, phenomenons and whatnot around us in order to make sense of our world. While trying to place you, I unexpectedly came to an understanding that I have my own individual classification for describing contemporary art. So far, I seem to have five specific classes which are: ugly art, pretty art, progressive art (art that makes people think), art that makes people laugh and art that shocks. In this (quite lately subconscious) scale of mine, your art belongs to two categories: to that of the progressive (design-like inventive) art and to the category of pretty art (that offers aesthetic pleasure). The last category of pretty art, that instantly offers something beautiful to the mind, is in deep decline in the contemporary art scene, because it is automatically associated with commerce and therefore labelled as ‘non-art’. And no artist wants to be a non-artist. So, for me it’s almost like an act of rebellion to create something as beautiful as your Wishing Wall, where all the wishes of an audience are being digitally transformed into colourful butterflies. Is that somehow compatible with your understanding?

VG: Wishing Wall has a special story behind it. The idea for the artwork came to us at the very same time when our daughter was born. It was the most happy and beautiful moment in our lives. I believe Wishing Wall really shares that love and happiness we have into the world. When seeing the documentation online, perhaps it looks like any other beautiful thing, but when it exhibited in various different sites, people had a much stronger connection to it. For example, when the piece showed in Istanbul, I was very touched to see a Kurdish woman wishing for peace in the region. Similarly, people were wishing for love when it exhibited in Athens. With this artwork we felt that we were giving something really positive and important to our audiences. Art definitely has to be critical, mirroring our society, pointing hidden stories out to people etc., but to be honest, sometimes, it is also vital for artists to remind others that there are wishes, and wishes have power, and life is full of surprises and miracles for everyone, big and small. I think people often need courage and special moments, instead of the constant rhetoric reminding us of how shit and corrupted life is and that there’s no light at the end of the tunnel.

MC: Yes, Wishing Wall is visually appealing and Varvara already explained the concept and reasons behind it, but commercially, we are not so well-to-do. For the record, we have never produced any commercial art piece to fit the curtains or respective wishes of our former gallery’s clients. Our piece Binoculars to… Binoculars from… (2013) talked about issues to do with surveillance. For that reason the artwork was not allowed to be shown last year in China. Tree of Hands (2015) was inspired by ideas of the Anthropocene. Again, one London art fair even found it too depressing in comparison to other works and removed it, obviously, referring that the work did not fit into the art fair which had to be a fun and happy event. And not naming My Name is 192.168.159.16, where people started to make strange faces when seeing interconnected human-like dolls hung with the ethernet cable. Coming back to your category ‘pretty’, I think what you are referring to is the finer look and quality of artworks. I am a perfectionist in my work, and my goal is to have an artwork looking and functioning perfectly when it comes to the production. Our artworks become our assets, and long gone are the student years when our messy installations ended up in the rubbish bin after every exhibition we held.

Wishing Wall, Barbican Centre, London, 2014. Photo: Andrew Meredith

Tree of Hands, 2015. Courtesy: Varvara& Mar

ML: It isn’t news that to be an artist anywhere is difficult these days. Mar, you are from Barcelona and Varvara, you are from Tartu, right? After three whole years of residencies in various countries, you could probably choose to stay put almost anywhere in the ‘big bad world’, but you have chosen Tallinn as the place to settle. What has been so tempting about this city for you both? What do you miss most about Spain, and what do you appreciate about living and working in Estonia?

MC: The decision to settle in Tallinn was actually quite rational. Varvara was about to give birth and we needed help and a home to live in. Varvara has a family apartment in Tallinn and her mother has been helping us a lot with our baby. As my parents had long working days, they could not offer to dedicate as much time as Varvara’s mother could. Another reason for choosing Tallinn was based on how little bureaucracy there is in this country – almost next to 0%. I love how people’s time is valued here. Spain is quite terrible in comparison. I find it easier to get things done in Estonia than in Spain from where I am from.

I see many people complaining about the climate here, but I prefer cold to hot weather. Also, the country is very beautiful; it has a lot of greenery and water, not to mention the long summer days, which are simply stunning.

To mention the things I miss living in Estonia, I love being able to meet and talk with people. In Estonia, it is not so easy to have spontaneous conversations like that, and making friends is rather difficult. Also, when dark times arrive, people stop smiling and get all serious. This situation actually became the inspiration behind us creating the installation Smile (2016).

VG: I had been living abroad for 8 years. I left Estonia when I went to do my master’s degree in Germany. In the end of 2013, when we moved to Tallinn, I had to reintegrate myself or start from zero, so to speak, getting to know people, establishing contacts, finding production and funding possibilities, searching for a studio space and much more in addition to both being young parents. To be honest, Tallinn has been a positive surprise for us. In the beginning it was just a practical decision which has transpired to be a really great city to live and work in, in the end. I think those of us, who are from Estonia, tend to complain a lot and fail to appreciate what we have. Now I can see things in comparison and understand the advantages. And believe me, we have quite a lot of them.

Smile. Exhibition ‘Remote Signals’, installation view, Tallinn, 2016. Photo: Jesus Rodriguez

ML: The little ‘miracles’ you have created using the help of digital state-of-the-art technology probably would’ve once been deemed as ‘witchcraft’ in the middle ages, or ‘magic’ later on in the 19th Century. I think it is still this moment of novelty that catches the eye of its audiences; have you ever used the same technological invention twice or is the combination of technology you use for creating every artwork always 100% original? Could we perhaps call your artworks ‘inventions’ and yourselves as ‘inventors’?

MC: Yes, we have often called ourselves inventors because we need to create tools for realising our extraordinary ideas. To be honest, we haven’t reused our work as much as I think we should. I often look at the artists who are producing the same works over and over again and I think that we should be profiting more from new knowledge that comes along with new work undertaken. Through that process, we often get exciting ideas for other new art pieces which we can also start to work on producing.

VG: I would like to point out one thing, that the use of technology for us is just a tool. The artwork has to be original and not the technology; whether the same or similar realisation process is used or not doesn’t matter.

ML: How do you find your ideas for creating new artworks? Are there goals you are working towards, or is it something quite the opposite where you discover something instead and then an idea of what this could become is born from that?

VG: It works both ways for us. We never know.

ML: What are you working on right now and what is your next big project going to be?

VG: At the moment the biggest project is Katusepoisid, which should be ready by mid January, 2017. It is a publicly-commissioned artwork for NUKU theatre and museum that opened the doors of it’s renewed complex on November 13, marking a start of a new era for the theatre house. (According to the Estonian law, at least 1 percent of the construction budget of public buildings must be allocated for the commissioning of artwork.)

MC: In February, we are going to show Smile at light festivals in Calgary and Melbourne. In March, we are producing and exhibiting in a Spanish artist and curator exhibition called PERRO in the Hobusepea gallery in Tallinn. And in October we will have a solo show in Draakoni gallery in Tallinn. In addition to that there are a number of shows that we hope we will get confirmation on soon.

ML: I think that great artists are often great philosophers. The 19th-Century French artist Paul Gauguin once named one of his paintings Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? What would be your response to these questions?

VG: Do you truly think Gauguin expected a response? I don’t think so.

Binoculars to… Binoculars from… MediaFacade Festival Helsinki. Courtesy: Varvara& Mar

Binoculars to… Binoculars from… MediaFacade Festival Helsinki. Courtesy: Varvara& Mar

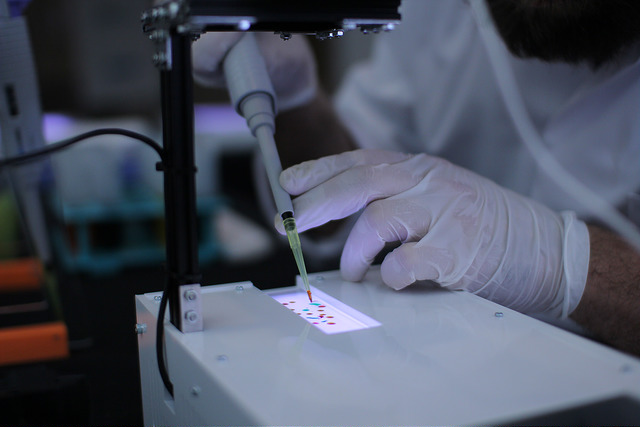

Data Drops, Data Transparency Lab conference 2015. Courtesy: Varvara& Mar

Data Drops, Data Transparency Lab conference 2015. Courtesy: Varvara& Mar

The Rhythm of Wind, 2016. Courtesy: Varvara& Mar

More information: http://www.varvarag.info/