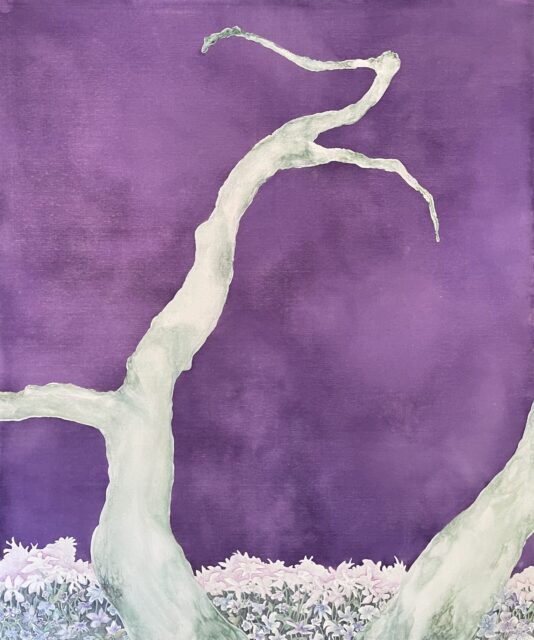

Kadi Estland, Blood May Have Been Planted. Dior fragrance, columns, teeth, seashell. 2019. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Marta Vaarik

A review of the dual exhibition ‘vomiting and crying vomiting and crying you are my sister you are my sister’ by Kadi Estland and Netti Nüganen at Tartu Art Museum from 18 January 2019 to 28 April 2019.

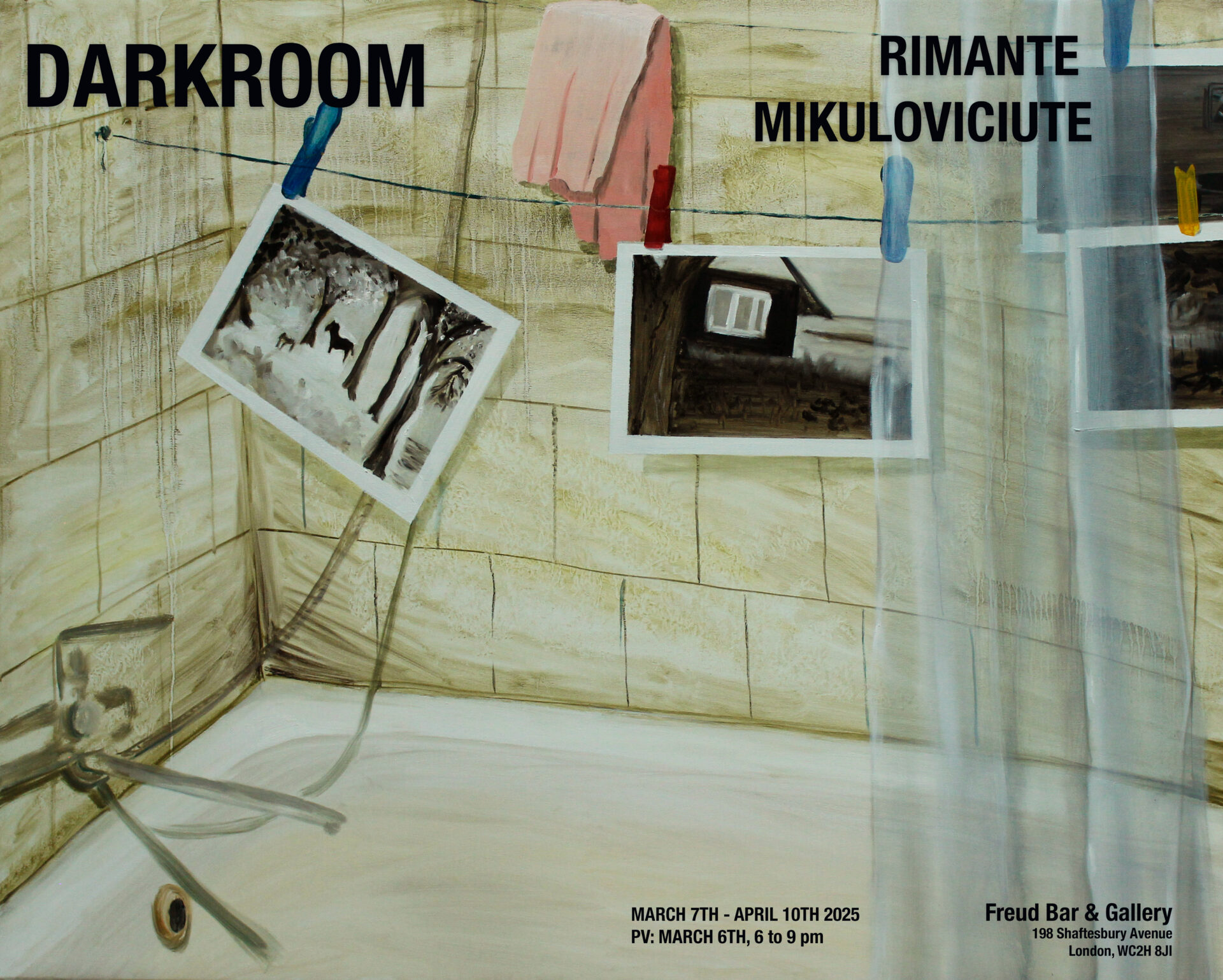

The title of the exhibition refers to a situation the artist Kadi Estland witnessed in the semi-public space of a ladies’ restroom in London: a woman was throwing up, while her sister was there providing help and care. Drawing on notions of sisterhood, solidarity, empathy, self-exposure and vulnerability, the exhibition puts forward a radical feminist perceptive, responding to the post-Soviet consciousness and its present neo-liberal premises. The exhibition’s principal achievement should be regarded as the alert awareness of peculiarities of local Estonian cultural and historical implications, which allows the artists Kadi Estland and Netti Nüganen, and the curator Marika Agu (from the Center for Contemporary Art in Estonia), to advance with politically charged statements concerning both the actual social and ideological climate in the Baltic States, and the burning question of the role and status of art, as well as the ethical dimension of the artist’s vocation.

Keeping a critical distance from market-oriented art, which, as Kadi Estland puts it in the interview in the exhibition’s leaflet, is created ‘for the elite to better their reputation’ (the ‘honourable’ Purvitis Art Prize in Latvia, sponsored by a gambling tycoon and adored by the local media, is a telling example), the show attempts to overcome the structural power-relations of the art world, and especially of art institutions, including the decision to avoid a hegemonic curator’s statement, to choose handwriting instead of industrial typography, and to work in a women-only team. Therefore, the exhibition aims to affirm the artist’s agency, spontaneity, openness and political vigilance.

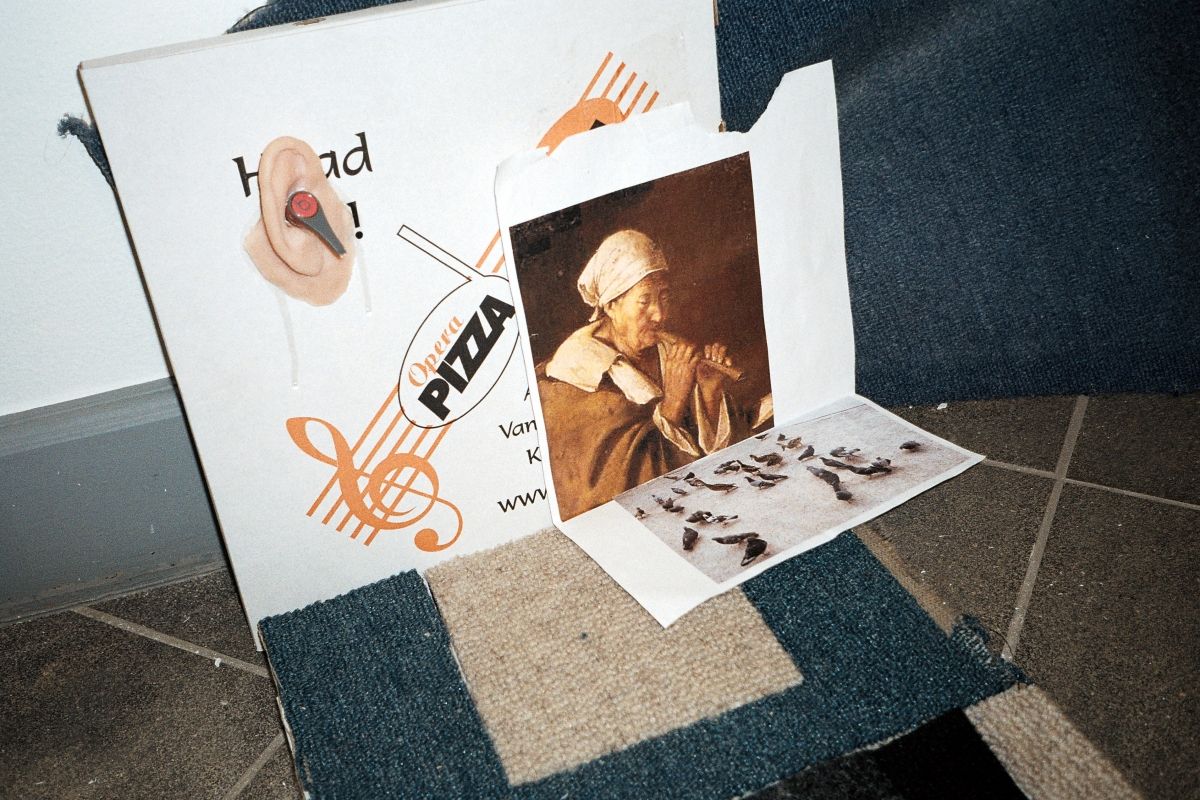

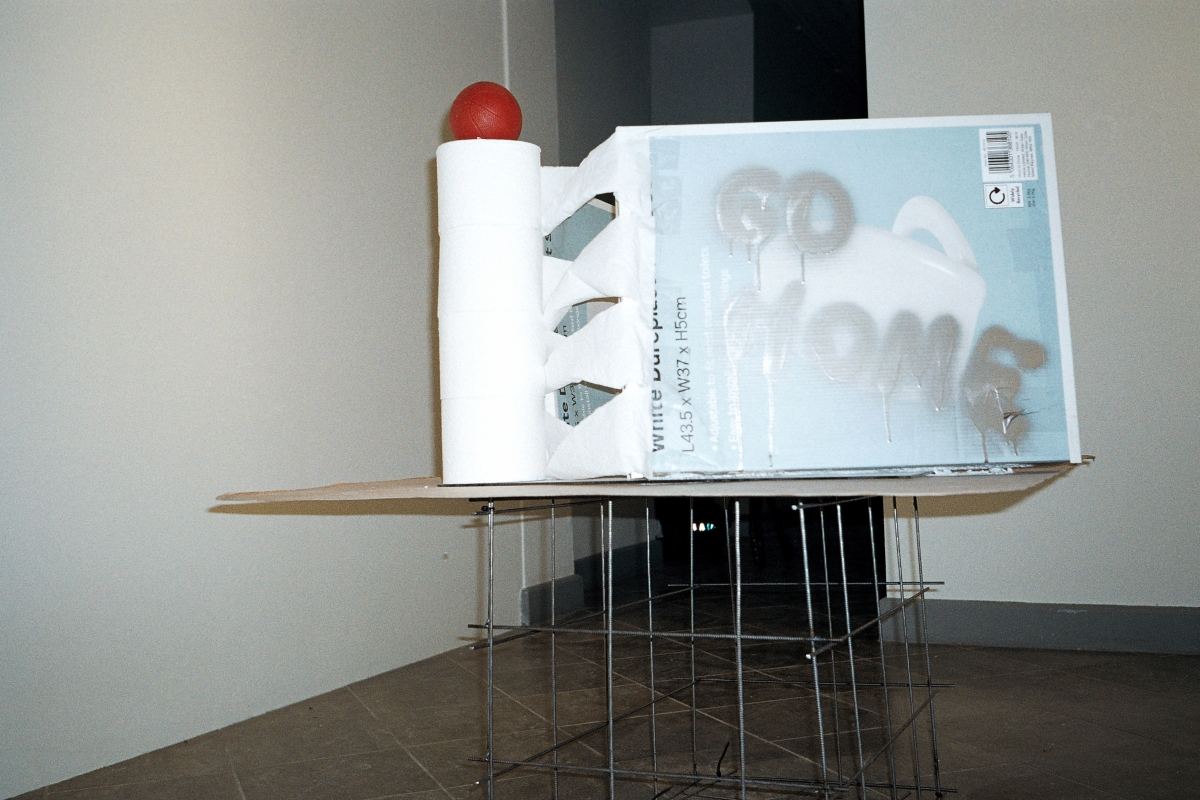

Kadi Estland’s works are improvised accumulations of everyday objects, be it old pieces of furniture, packaging, scraps of textiles, building materials, worn-out teddy bears or household waste. The down-to-earthiness of these installation is emphasised by the artist herself, stating that the works could in fact be made by anyone, and that outside the institutional context provided by the museum, they would be viewed simply as garbage. The ‘devaluation’ of artistic craftsmanship, and the de-aestheticisation of its outcome, is a strategy intended to strip art of any elitist refinement, apolitical self-sufficiency, and pretension to good taste. The emerging ‘void’ is refilled with playfulness, wit, and above all, political urgency and personal sorrow.

Exhibition view, i’m vomiting and crying i’m vomiting and crying: you are my sister you are my sister. Photo by Marta Vaarik

Critical comments on the exploitative social structures and inequalities maintained by patriarchy and capitalism reveal individual vulnerabilities, panic attacks, health disorders, and outbreaks of violence and anger, as well as futile aspirations and borrowed fantasies which are staggering, like an old kitchen cupboard from the Soviet era. Hopeless poverty, ageing and alienation are contrasted with the shabby idols and promises of a better life produced by travel agencies, shopping malls or a box of tranquilisers. The need to show off in order to prove one’s status and economic achievements is a typical post-Soviet syndrome (the pakazuha phenomenon), which is determined by the trauma, beggary and limited possibilities of the Soviet past, as well as by the insecurities and complexes of today, when the hope of a bright future for everyone is attainable only by a few: the lucky, the privileged, and the wealthy. Vulnerable identities, such as residents of social housing in London, supermarket cashiers, and young mothers who are subject to over-medicalisation and social isolation in the debris of diapers, definitely do not fit the model of the perfect citizen. These subjects are ephemeral and marginalised, traces of their faces are mashed up until they become formless, and their low status corresponds to the cheap appearance of the installations which can easily be overlooked and dismissed. Contrary to the box-man of Kobo Abe, who decides to lock himself in a box in order to reject the world (as described in his celebrated 1973 novel), the contemporary homeless people that Kadi Estland refers to inhabit cardboard boxes because the world seems to have rejected them instead.

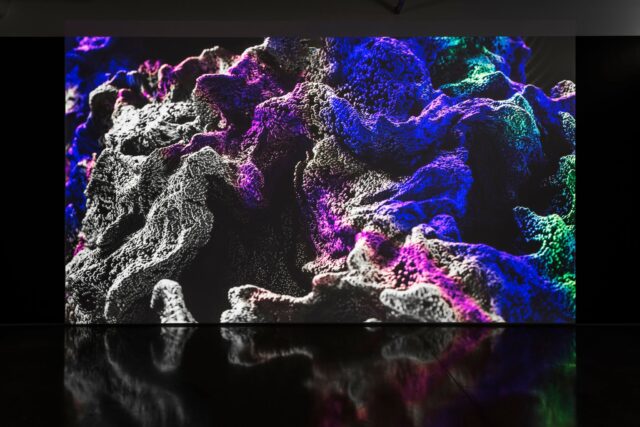

The video works by Netti Nüganen in the next rooms seem to benefit from the contextually rich and symbolically intense installations by Estland, gaining some additional conceptual weight that would otherwise have been lacking. The construction of the image of a body-builder and its potential for questioning ‘fragile femininity’, the dramatic enactment of an opera diva, the blend of naivete, hysteria and self-irony that are characteristic of Nüganen’s videos ‘i’m rules’ and ‘i’m rules II’, are captivating, of course. However the main shortcoming is the problematic intention of ‘liberating words from their meanings’. While on one hand it could imply the idea of deconstruction and a criticism of phallogocentrism, on the other hand, as it turns out, this could be merely an effect of over-stimulation, the fragmentation of the consciousness and confusion caused by the extensive use (and misuse) of social media. Words do not need to be liberated from their meanings: these meanings almost inevitably drop off themselves, and the challenge is to restore them for both political and private purposes. Similarly, the distinction between language (intellectual capacity, rationalism) and emotions (intuition, irrationalism) is rather questionable, and in fact plainly affirms a binary dichotomy and traditional gender order, which, I believe, could scarcely be the artist’s aim.

Netti Nüganen. i’m rules I. 16′. 2017. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Marta Vaarik

The performance by Netti Nüganen which took place on 4 April (simultaneously with the launch of the exhibition catalogue, which also features texts by both artists) can hardly be called successful either. Even though some traces of logic may possibly be found in it, nonetheless the performance, or ‘act’, as the artist prefers to call it, unfortunately lacked choreographical coherence, inward structure and kinetic precision. While these notions can of course be perceived as representatives of an outdated aesthetic tradition, in contemporary art practice, they need to be reworked, and not dismissed, which, it seems to me, Netti Nüganen has decided to do. The need to verbally announce the end of it was also indicative of performative failure. The whole act was possibly merely an improvisation, and in this case the acting qualities of the performer need to be stronger.

The exhibition’s most significant contribution to the contemporary art scene is its vocalisation of the potential of artists for enacting radical political agendas and enriching the critical discourse of feminist enquiries. The institutional background of the museum was especially successful in this case, since it constituted the very place where not only does ‘garbage’ acquire the value of a work of art, but also erased identities, muffled voices and suppressed emotions, the vomits and tears of today’s society, become obvious and demand immediate attention.

Photo reportage from the exhibition: http://echogonewrong.com/photo-reportage-exhibition-vomiting-crying-vomiting-crying-sister-sister-kadi-estland-netti-nuganen-tartu-art-museum/

Netti Nüganen. Videostill from i’m rules II. 5-channel video installation, 16′. 2019. Courtesy of the artist

Kadi Estland, There Are No Tears in Heaven. Pizza box, headphones, carpet, photo of the painting “Old Woman Playing a Flute”. 2019. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Marta Vaarik

Exhibition view, i’m vomiting and crying i’m vomiting and crying: you are my sister you are my sister. Photo by Marta Vaarik

Exhibition view, i’m vomiting and crying i’m vomiting and crying: you are my sister you are my sister. Photo by Marta Vaarik