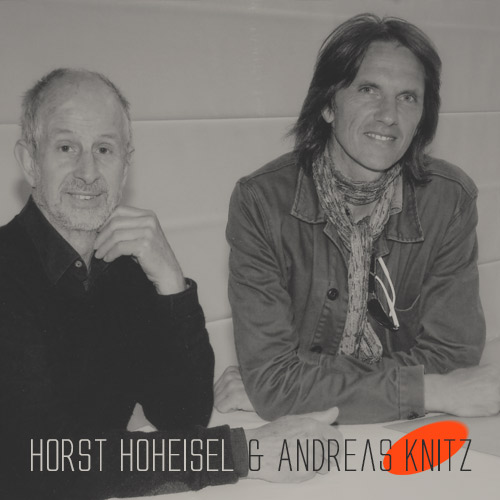

Renowned for their so-called ‘counter-monuments’, the world famous German artistic duo Horst Hoeheisel and Andreas Knitz will visit Lithuania this year as one of the participants at the Kaunas Biennial. Scientist and sculptor Horst and architect Andreas create sensational and thought-provoking monuments that evoke painful topics and believe that the perspective of the perpetrators is as important as that of the victims. We recently talked to them about their ‘counter-monuments’ project, about history in general and what lessons can be learned from engaging with their work.

Renowned for their so-called ‘counter-monuments’, the world famous German artistic duo Horst Hoeheisel and Andreas Knitz will visit Lithuania this year as one of the participants at the Kaunas Biennial. Scientist and sculptor Horst and architect Andreas create sensational and thought-provoking monuments that evoke painful topics and believe that the perspective of the perpetrators is as important as that of the victims. We recently talked to them about their ‘counter-monuments’ project, about history in general and what lessons can be learned from engaging with their work.

You’re collaborating in creating new shapes of monuments, known as ‘counter-monuments’ or ‘negative-monuments’. For the Lithuanian public this may well be a vague concept that very few have heard of. Could you explain the difference between so-called conventional monuments and your ‘counter-monuments’ by giving some examples?

Conventional memorials are normally made from marble or bronze and stand on pedestals for eternity. In our daily lives nobody takes much notice of them. They’re like ghosts standing around in our cities. Our ‘counter monument’s are almost invisible, are negative forms sunk into the ground. One may only look into the darkness of a hole, such is the case with the Aschrott Fountain in Kassel, or kneel down and touch a memorial steel plate warmed to human body temperature as in the Former Concentration Camp of Buchenwald, or the monument may move from one city to another, like the Monument of the Grey Buses. We want to create situations where people can feel the presence of the absence and think about the lost forms and lost victims, as well as about the perpetrators. We won’t replace the lost forms and fill the absence with big monuments.

Because of their conceptual nature, ‘counter-monuments’ invite those who visit them to reflect on painful periods of the past and encourage the development of their individual understanding of historical events, very often in interactive ways. Is it easy to achieve engagement when talking about traumatic periods of our past? Do people generally show an intention to collaborate?

In Kassel, for example, over 1,000 school pupils, students and ordinary citizens dedicated one individual memory stone for one deported and murdered Jewish citizen which we then assembled into a single memorial, the memorial-stone-collection at the deportation gate at the Main Station. It always needs time to start such an interactive memory process. Sometimes more than a year, but if you don’t try to pressurize people and and give them freedom to make their own decisions, people will collaborate.

Not all of your ‘counter monuments’ are long-lasting. Some are designed to change all the time. How well do you think they succeed in generating a long-lasting reflection and discussion about the past?

We believe there are no long-lasting reflections. Every generation generates its own past and reflections about history. Every new political system destroys the monuments of the former system and builds its own new ones, as is the case in Lithuania. Memory isn’t stable, and memorials aren’t stable either.

A lot of your memorials were built in Germany and are dedicated to the victims of the Holocaust. Why do you think it’s important for a nation to commemorate such experiences even if it doesn’t see them from a victim’s perspective?

It’s always much easier to identify with the victims rather than with the perpetrators, but Germany is a nation of perpetrators and this should be commemorated too. This can be done with memorials that are normally made for the victims or for the heroic history and victories of a nation as well as with ‘counter-monuments’. There were Lithuanian Nazi collaborators involved in the Holocaust as well. To prevent history repeating itself, the perspective of the perpetrators is as important if not more important than the perspective of the victim’s. There are no victims without perpetrators.

You’ve worked in many different places all over the world. Have you noticed any themes or issues that link these places together?

In Latin America they have familiar issues around the theme of military dictatorships. In all countries where dictatorships, racism and genocides take place you have a similar problem of how to commemorate the victims and the perpetrators. But it also depends on the traditions of each different culture. In Buddhist countries for example, such as Cambodia that suffered under the dictatorship of Pol Pot, they commemorate victims with an altars of food. Because these victims don’t die as such, and are reincarnated. A monument such as we Christians build would be a sign of colonialism there. The rituals of commemoration, like the cultures themselves, are different. Therefore, they deal differently with issues of oblivion and displacement.

Why do you think today’s society is so eager to forget? What’s the key to gaining an appreciation of history and learning lessons from it?

We’re not so sure, if society today is eager to forget. We’re really afraid of the future and are subsequently orientated towards the past. But we look very selectively into history. You see this now during the preparation for the centenary of Lithuanian independence in 1918. The Lithuanian government will build many memorials, including many equestrian statues commemorating the distant past when Lithuania extended from Baltic coast to the Black Sea.

Is this a lesson Lithuania learned from its history?

Horst, you visited Lithuania back in 2009 when Vilnius was the European Capital of Culture. Back then you created an installation at the Vilnius Vytė Nemunėlis elementary school called School Windows of Memory in which you installed images of a former synagogue that once stood in that place into the windows of the school. Could you tell us a little more about this project? Do you think that ‘counter-monuments’ like this one might be a useful way of teaching history to those who didn’t experience it themselves?

It would have been possible for the pupils to have learned something about the history of the place they live in and the lost Jewish community of Vilnius, but I was only allowed to do this during the school holidays. The director insisted that I took the transparencies of the synagogue in the school windows off before the pupils returned to school. A perfect opportunity for everyone to learn together was wasted.

When I was working on the project I encountered a lot of anti-Semitic sentiment. The school Director didn’t want to confront the children with their own history. He preferred that they should forget about it. And the official organisers of the European Capital of Culture 2009 wanted to forget too. In the official event publications, the history of the country mentioned the Soviet occupation but didn’t say a thing about the Nazi period between 1941 and 1944. telling the history of Lithuania there appeared only the occupation by the Soviets (1941-1990!). I hope this won’t happen again when Kaunas becomes European Capital of Culture in 2022.

During this year’s Kaunas biennial the two of you will be working on a couple of projects. Could you tell us a little bit about what we might see and what attitude you recommend visitors to the Biennial should bring with them?

Instead of building and installing something new we’ll recycle something and put it in a new context. The visitors should be curious, think about the past and the change of political systems. Perhaps they won’t like and won’t accept our art. But if the work hurts a bit, then perhaps people will think about it a bit longer. If they like immediately and it’s accepted, then it’s often very soon forgotten too.

This autumn Horst Hoheisel and Andreas Knitz will participate in the debate ‘Questionable Memory – Questionable Public Spaces’ taking place during the opening weekend of the 11th Kaunas Biennial.

The discussion will take place on September 16 and 17 in the VDU Daugiafunkcinis mokslo ir studijų centras (VMU Multifunctional Science and Studies Centre) at Putvinskio 23.

The participants will include prof. James E. Young, dr. Horst Hoheisel and Andreas Knitz, Jochen Gerz, dr. Matthew Rampley, Manca Bajec, dr. Rasa Antanavičiūtė, dr. Giedrė Jankevičiūtė and dr. Giedrė Mickūnaitė.

11th Kaunas Biennial THERE AND NOT THERE: (Im)possibility of a monument

15 09 2017 – 30 11 2017